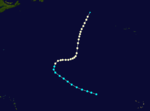

1903 Atlantic hurricane season

| |

| Season summary map | |

| First system formed | July 21, 1903 |

|---|---|

| Last system dissipated | November 25, 1903 |

| Strongest storm1 | Two – 958 mbar (hPa) (28.29 inHg), 120 mph (195 km/h) |

| Total depressions | 10 |

| Total storms | 10 |

| Hurricanes | 7 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 1 |

| Total fatalities | 222 |

| Total damage | $18.5 million (1903 USD) |

| 1Strongest storm is determined by lowest pressure | |

1901, 1902, 1903, 1904, 1905 | |

The 1903 Atlantic hurricane season featured seven hurricanes, the most in a season since 1893. The first tropical cyclone was initially observed in the western Atlantic Ocean near Puerto Rico on July 21. The tenth and final system transitioned into an extratropical cyclone well northwest of the Azores on November 25. These dates fall within the period with the most tropical cyclone activity in the Atlantic. Six of the ten tropical cyclones existed simultaneously.

Of the season's ten tropical storms, seven of those strengthened into a hurricane. One of the seven hurricanes deepened further into a major hurricane, which are tropical cyclones that reach at least Category 3 on the modern day Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale. The second, third, and fourth systems left the most significant impacts during this season. The second storm, which struck Jamaica in August, devastated Martinique, Jamaica, and the Cayman Islands. At least 149 deaths were attributed to this storm, while it also caused $10 million (1903 USD) in damage in Jamaica alone. The third cyclone made landfall in Florida twice in mid-August, leaving 14 fatalities and about $500,000 in damage. Only a few days later, the fourth cyclone struck New Jersey. The storm impacted many areas in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States and caused 57 deaths and about $8 million in damage. Additionally, the remnants of the eighth tropical cyclone caused severe flooding in the Mid-Atlantic.

The Atlantic hurricane reanalysis project also indicated but could not confirm the presence of four additional tropical depressions throughout the season. However, the reanalysis added a previously undetected tropical storm in late October to the Atlantic hurricane database (HURDAT). Reanalysis also resulted in the eighth cyclone being downgraded from a hurricane to a tropical storm.[1]

Season summary

%2C_en_1903_-_les_Ruines_dans_la_Rue_Saint-Denis%2C_a_Fort-de-France.jpeg)

Tropical cyclogenesis began with the development of the first system on July 21 in the western Atlantic near Puerto Rico. This was the only storm in the month of July. Likewise, August also featured one storm. The second system was the most intense tropical cyclone of the season, peaking as a Category 3 hurricane with maximum sustained winds of 120 mph (195 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 958 mbar (28.3 inHg). This was also the first major hurricane in the Atlantic basin since the second storm of 1900 and the first in the Caribbean Sea since the 1899 San Ciriaco hurricane. September was the most active month of the season, with four systems developing, three of which intensified into a hurricane. In October, there were three tropical storms, with one intensifying into a hurricane. The only November tropical cyclone, as well as the final system of the season, developed on November 17 and transitioned into an extratropical cyclone while northwest of the Azores on November 25.[2]

The season had a total of 10 tropical storms, 7 of which intensified into a hurricane. This marked the most hurricanes in a season since the total of eight in 1893.[3] There may have been an additional four tropical depressions throughout the season, but the data obtained by the Atlantic hurricane reanalysis project was inconclusive. The reanalysis added a previously undetected tropical storm in late October to the Atlantic hurricane database (HURDAT). Reanalysis also resulted in the eighth cyclone being downgraded from a Category 2 hurricane to a tropical storm.[1] Nearly all of the season's 10 tropical cyclones impacted land. Collectively, the storms caused over $18.5 million in damage and at least 222 fatalities.[4]

The season's activity was reflected with an accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) rating of 102.[3] ACE is, broadly speaking, a measure of the power of the hurricane multiplied by the length of time it existed, so storms that last a long time, as well as particularly strong hurricanes, have high ACEs. It is only calculated for full advisories on tropical systems at or exceeding 39 mph (63 km/h), which is tropical storm strength.[5]

Storms

Hurricane One

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | July 21 – July 26 | ||

| Peak intensity | 80 mph (130 km/h) (1-min) <999 mbar (hPa) | ||

According to historical weather maps, an area of disturbed weather developed a closed circulation early on July 21 while located about 100 mi (160 km) northeast of the Samaná Peninsula of Dominican Republic, becoming the first tropical cyclone of the season.[6][2] The storm moved northwestward until about 12:00 UTC on July 22, at which time it curved northward, before turning northeastward about 24 hours later. Early on July 24, it intensified into a Category 1 hurricane. The hurricane strengthened slightly further, peaking with maximum sustained winds of 80 mph (130 km/h) six hours later. The system began weakening early on July 24, falling to tropical storm intensity around 12:00 UTC. Accelerating to the east-northeast, the storm also began to lose tropical characteristics and transitioned into an extratropical cyclone at 06:00 UTC on July 26, while situated about 430 mi (690 km) south-southeast of Cape Race, Newfoundland.[2] Shortly before, a ship recorded a barometric pressure of 999 mbar (29.5 inHg), the lowest in relation to the storm.[6] The extratropical remnants continued east-northeastward and dissipated late on July 26.[2]

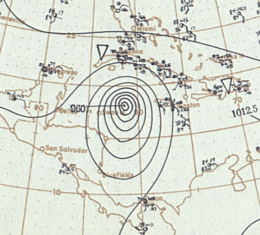

Hurricane Two

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | August 6 – August 16 | ||

| Peak intensity | 120 mph (195 km/h) (1-min) 958 mbar (hPa) | ||

A tropical storm was first observed about 1,160 mi (1,870 km) east-southeast of Barbados, early on August 6. The system moved generally west-northwestward and strengthened into a hurricane about 24 hours later. Early on August 9, it struck Martinique as either a strong Category 1 or a weak Category 2 hurricane. The storm entered the Caribbean Sea shortly thereafter. Around 12:00 UTC, the cyclone intensified into a Category 3 hurricane. Between 06:00 UTC and 12:00 UTC on August 11, it struck Jamaica near Morant Point with winds of 120 mph (195 km/h). At 06:00 UTC on August 12, while brushing Grand Cayman, the hurricane peaked with maximum sustained winds of the same intensity and a minimum barometric pressure of 958 mbar (28.3 inHg),[2] observed by the Governor Blake.[6] The system weakened to a Category 2 around the time of landfall near Playa del Carmen, Quintana Roo, early on August 13, with winds of 100 mph (155 km/h). By 12:00 UTC, the storm further weakened to a Category 1. After crossing the Yucatán Peninsula and emerging into the Gulf of Mexico early on August 14, the hurricane failed to re-strengthen. Around 00:00 UTC on August 16, it made landfall north of Tampico, Tamaulipas, with winds of 80 mph (130 km/h). The hurricane soon weakened to a tropical storm and dissipated over San Luis Potosí late on August 16.[2]

In Martinique, hundreds of homes were deroofed in Fort-de-France,[7] while about 5,000 people were left homeless in the villages of Fond, Fourniols, La Haye, Recluce, and Tivoli, all of which were established after the eruption of Mount Pelée in 1902. The hurricane also left extensive damage to crops and eight fatalities.[8] In Jamaica, several communities were completely or nearly destroyed, including Manchioneal,[9] Port Antonio,[10] and Port Maria.[11] Thousands of homes also suffered damage in the capital city of Kingston. Banana crops were devastated so severely that many growers were forced into bankruptcy. Numerous ships were wrecked, particularly on the north coast of the island. There were at least 65 deaths and about $10 million in damage.[10] At the Cayman Islands, more than 200 houses and seven of eight churches on Grand Cayman were destroyed or heavily damaged. Of the 23 ships in the harbor, only the Governor Blake survived. Most of the crews on board those ships were reported killed, but loss of life on shore was minimal.[6] The storm also caused heavy damage on the Yucatán Peninsula. Many ships were wrecked and communications were cutoff in several places.[6][12] In the Tampico area, there was considerable damage to the port and many ships being sunk or driven ashore. Much of the land between Tampico and Cárdenas in San Luis Potosí was submerged due to flooding.[13] In all, the storm is believed to have killed at least 149 people.[14]

Hurricane Three

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | September 9 – September 16 | ||

| Peak intensity | 90 mph (150 km/h) (1-min) 974 mbar (hPa) | ||

Reanalysis indicates that a 60 mph (100 km/h) tropical storm originated near Mayaguana in the Bahamas around 06:00 UTC on September 9,[2] though lack of data suggests that this system likely developed earlier.[1] Moving northwestward, the cyclone became a Category 1 hurricane around 12:00 UTC on the following day. Late on September 10 and early on September 11, the storm passed near Nassau. The hurricane then turned to the west-northwest on September 11 and moved just north of the Bimini Islands.[2] As it crossed the Bahamas, the system produced hurricane-force winds on some islands, with an estimated wind speed as high as 90 mph (140 km/h) in Nassau. Damage to crops and buildings occurred, but no deaths were reported over the island chain.[15]

Late on September 11, the storm made landfall near Fort Lauderdale, Florida, with winds of 85 mph (140 km/h).[2] The Inchulva capsized near Delray Beach, drowning nine of her crew members.[16] The cyclone caused severe wind damage in present-day Broward and Palm Beach counties,[17] although most of the losses were to crops such as sugarcane.[18] The hurricane weakened to a tropical storm while crossing Florida, but re-intensified into a hurricane over the Gulf of Mexico on September 12. Peaking with maximum sustained winds of 90 mph (150 km/h), the storm made landfall near Panama City around 23:00 UTC on September 13.[2] In Northwest Florida, Alabama, and Georgia, the cyclone produced widespread rainfall, causing some crop damage.[18][19] Additionally, a storm surge caused boats to be blown ashore in the Florida Panhandle. In all, the storm killed 14 people in Florida and produced $500,000 in damage.[20] After falling to tropical storm intensity early on September 14, the storm weakened to a tropical depression on September 16, several hours before dissipating over South Carolina.[2]

Hurricane Four

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | September 12 – September 17 | ||

| Peak intensity | 100 mph (155 km/h) (1-min) 990 mbar (hPa) | ||

A 70 mph (120 km/h) tropical storm was first observed about 550 mi (885 km) northeast of Antigua early on September 12. The storm moved relatively quickly to the northwest. Late on September 14, it strengthened into a Category 1 hurricane. On the following day, the storm began curving to the north-northwest. Intensifying further, the cyclone became a Category 2 hurricane late on September 15, peaking with maximum sustained winds of 100 mph (155 km/h). At the time, it was situated about 110 mi (190 km) southeast of Cape Hatteras, North Carolina. The storm weakened back to a Category 1 hurricane at 00:00 UTC on September 16. About 11 hours later, the hurricane made landfall near Avalon, New Jersey, with winds of 80 mph (130 km/h).[2] In 1992, Jerry Jarrell, later director of the National Hurricane Center, estimated a barometric pressure of 990 mbar (29 inHg) at landfall, which would be the lowest in association with the hurricane.[1] After moving inland, the system quickly weakened to a tropical storm late on September 16. The storm transitioned into an extratropical cyclone over New York near Lake Ontario at 12:00 UTC on September 17. The extratropical remnants soon dissipated over Ontario.[2]

In North Carolina and Virginia, the storm brought nearly hurricane-force winds and rough surf.[21] Some boats were beached along the coast of Virginia.[22] Near Chincoteague, the schooner Beatrice capsized, drowning 28 people.[23] Hundreds of birds were killed and fell to the ground near Old Point Comfort, many stripped of their feathers. The outer rainbands of the storm produced heavy rainfall near Washington, D.C., canceling a Major League Baseball game between the Detroit Tigers and the Washington Senators after the field was flooded.[22] Along the Delaware coast, the schooner Hattie A. Marsh was smashed against the rocks, killing five people.[23] The hurricane caused severe damage in New Jersey, especially in Atlantic City.[24][25] Throughout the coastal regions, strong winds downed all telephone and telegraph wires. Additionally, the winds destroyed the roofs of an estimated 50 to 60 cottages.[24] Several streets were flooded, with severe transportation delays reported.[26] One indirect death occurred in Cape May when a man, unable to see owing to the hurricane, drove into a train. Damage in New Jersey was approximately $8 million.[24] In New York City, high winds swayed buildings, spires, and bridges, overturning wagons on the Brooklyn Bridge. At least a few buildings were deroofed and many homes were flooded or damaged, especially in Brooklyn. One death occurred in the city.[27] On Long Island, President Theodore Roosevelt directly experienced the effects of the hurricane while on a yacht. The life of the president was briefly threatened due to the rough conditions, though none on board of the yacht suffered any problems from the hurricane.[28] Overall, the storm caused 57 fatalities.[14]

Tropical Storm Five

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | September 19 – September 26 | ||

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min) 1003 mbar (hPa) | ||

Historical weather maps indicated that a tropical depression developed just south of the Turks and Caicos Islands early on September 19.[2][6] The depression trekked generally northward and remained weak for the next few days. By September 22, the system intensified into a tropical storm. Turning east-northeastward on September 24, the storm peaked with maximum sustained winds of 60 mph (95 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 1,003 mbar (29.6 inHg),[2] which was observed by a ship.[6] Thereafter, it accelerated and slowly weakened, falling to tropical depression intensity early on September 26. The system dissipated by 18:00 UTC while situated about 450 mi (720 km) southeast of Sable Island.[2]

Hurricane Six

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | September 26 – September 30 | ||

| Peak intensity | 110 mph (175 km/h) (1-min) <988 mbar (hPa) | ||

Historical weather maps note that a tropical storm was first observed about 415 mi (670 km) northeast of Anguilla early on September 26.[6][2] Initially, the storm moved west-northwestward, but curved northwestward late the following day. At 00:00 UTC on September 28, the cyclone intensified into a Category 1 hurricane and then a Category 2 hurricane 12 hours later while curving to the northeast.[2] While passing near Bermuda late on September 28, the storm attained its peak intensity with maximum sustained winds of 110 mph (175 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 988 mbar (29.2 inHg), which was observed in Hamilton.[1] The system then began to accelerate and weaken, falling to Category 1 intensity at 00:00 UTC on September 30. Six hours later, the hurricane transitioned into an extratropical cyclone while located about 495 mi (700 km) southeast of Cape Race, Newfoundland. The remnants moved continued rapidly northeastward and dissipated later that day.[2]

In Bermuda, the strongest observed wind speed was 74 mph (119 km/h). The winds uprooted a number of cedar trees and broke off large palmettos off palm trees. Several buildings and homes were damaged. A newly constructed extension on the Princess Hotel "collapsed like a pack of cards". In St. George's, a wall that collapsed near the Royal Engineers quarters killed a former soldier. Heavy rainfall on the island washed out many roads.[6] A landslide occurred, shearing off a portion of the cliff at Deep Bay. The resulting earth trembling and noise created from the slide resembled an earthquake.[29] Along the coast, rough seas wrecked a number of boats, while several stone docks and seawalls were severely damaged or destroyed. Another death occurred after an engineer on Ireland Island was swept out to sea and drowned.[6]

Hurricane Seven

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | October 1 – October 9 | ||

| Peak intensity | 100 mph (155 km/h) (1-min) | ||

A strong tropical storm was first observed about 300 mi (480 km) east of Barbuda early on October 1,[2] according to historical weather maps and ship data.[6] Moving northwestward, it intensified into a Category 1 hurricane about 24 hours later. The storm then curved north-northeastward late on October 2. Strengthening into a Category 2 hurricane around 12:00 UTC on October 4, the cyclone peaked with maximum sustained winds of 100 mph (155 km/h). It then briefly turned east-northeastward, before recurving east-southeastward. Late on October 5, the hurricane weakened back to the Category 1. The storm began to decelerate and execute a cyclonic loop late on October 6. After about 24 hours, it began moving east-northeastward to northeastward. Early on October 9, the hurricane weakened to a tropical storm. Late that day, it transitioned into an extratropical cyclone while situated 680 mi (1,090 km) south-southwest of Flores Island in the Azores.[2]

Tropical Storm Eight

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | October 5 – October 10 | ||

| Peak intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min) 997 mbar (hPa) | ||

A tropical storm was first observed by ships early on October 5,[6] while situated about 160 mi (260 km) northeast of San Salvador Island in the Bahamas. The storm nearly drifted northeastward while strengthening slowly over the next few days. Early on October 8, the cyclone curved north-northeastward.[2] The storm attained its peak intensity with winds of 70 mph (110 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 997 mbar (29.4 inHg) on October 9 while passing west of Bermuda; both were based observations from a ship. Reanalysis also resulted in the eighth cyclone being downgraded from a Category 2 hurricane to a tropical storm[6] Thereafter, the system began weakening and transitioned into extratropical cyclone around 12:00 UTC on October 10, while located about 255 mi (410 km) north of Bermuda.[2]

Although the remnant system became indistinguishable by late on October 10,[2] the remnants contributed to severe flooding along the East Coast of the United States. In North Carolina, poor weather conditions in Kitty Hawk prevented the Wright brothers from flying their glider or assembling the untested airplane.[30] In Virginia, strong winds toppled trees and knocked out communications in cities such as Richmond and Norfolk, where a tree brought from Napoleon Bonaparte's grave in Paris, France, was uprooted. Wires were downed, completely disrupting communication. One death occurred inland when a man in Leesburg drowned while walk across a log on the Little River. Rough seas capsized nine vessels offshore Virginia, resulting in three deaths. Waves lashing the Back River Light caused the stones on its structure to move out of place.[22]

The storm caused severe flooding states such as New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania. In New Jersey, some areas experienced rainfall totals of about 14 in (360 mm) over the course of four days.[31] In Paterson, seven bridges were destroyed and two others were severely damaged. Approximately 10.3 mi (16.6 km) of streets in the city were inundated. About 1,200 people fled their homes and took refuge at Paterson Armory. About 20% and 20% of the land in Passaic and Wallington were inundated, respectively.[31] Damage in New Jersey reached about $7 million. Twenty deaths occurred, with two from drowning incidents, one from a heart attack, and seventeen others from a flood-related train crash near Trenton. Along the Delaware River, nine bridges connecting New Jersey and Pennsylvania were destroyed.[30] In Pennsylvania, houses in Easton were swept into the river and destroyed after colliding with bridges. The Lehigh River overflowed into West Easton, damaging all businesses in the city.[32] In New York, about 10 in (250 mm) fell in New York City over a 48-hour period.[22] A number of businesses and homes were flooded, while some areas of the city were inundated with 2 ft (0.61 m) of water. Transportation by ferry, trolley, and railroad were also disrupted. A flooded conduit damaged 70 telegraph lines.[33] In Poughkeepsie, two deaths occurred due to a landslide.[34]

Tropical Storm Nine

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | October 21 – October 24 | ||

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min) 1008 mbar (hPa) | ||

A westward moving disturbance was first noted between Barbados and Grenada on October 19 and later Hispaniola.[6] By early October 21, the system developed into a tropical depression near Turks and Caicos Islands. [2] The depression initially moved north-northwestward across the eastern Bahamas, remaining weak during its passage. After reaching the open Atlantic, the cyclone intensified into a tropical storm by 12:00 UTC on October 23. Strengthening continued, and by early on October 24, the storm peaked with maximum sustained winds of 60 mph (95 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 1,008 mbar (29.8 inHg),[2] both of which were observed by ships.[6] However, the system transitioned into an extratropical cyclone by 18:00 UTC while situated about 190 mi (310 km) southeast of Cape Lookout in North Carolina.[2] The remnants accelerated ahead of a cold front and later struck Newfoundland,[2][6] before dissipating over the Labrador Sea on October 27.[2]

Hurricane Ten

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | November 17 – November 25 | ||

| Peak intensity | 80 mph (130 km/h) (1-min) 985 mbar (hPa) | ||

Historical weather maps indicated the final storm on the season beginning early on November 17,[6] while located about 780 mi (1,260 km) west-northwest of Santo Antão island in Cape Verde. The storm strengthened slowly and moved northwestward for the next few days, until curving northeastward late on November 19. At 06:00 UTC on the following day, the cyclone intensified into a Category 1 hurricane. Shortly thereafter, the hurricane turned eastward and then north-northeastward by November 22. On the following day, it peaked with maximum sustained winds of 80 mph (130 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 985 mbar (29.1 inHg),[2] which was observed by a ship.[6] The hurricane continued moving north-northeastward for a few days, until transitioning into an extratropical cyclone while located about 480 mi (770 km) northwest of Corvo Island in the Azores late on November 25.[2]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Christopher W. Landsea; et al. Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT. Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved April 26, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 National Hurricane Center; Hurricane Research Division (July 6, 2016). "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)". United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved December 5, 2016.

- 1 2 Atlantic basin Comparison of Original and Revised HURDAT. Hurricane Research Division; Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. April 2016. Retrieved May 30, 2016.

- ↑ "Hurricane Spreads Havoc in Jamaica". The New York Times. Kingston, Jamaica. August 13, 1903. p. 1. Retrieved May 30, 2016.

- Edward N. Rappaport; Jose Fernandez-Partagas (April 22, 1997). The Deadliest Atlantic Tropical Cyclones, 1492-1996 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved May 17, 2016.

- Jay Barnes (2007). Florida's Hurricane History. University of North Carolina Press. pp. 84–85. ISBN 978-0-8078-3068-0. Retrieved May 18, 2016.

- "Hurricane Sweeps Atlantic Coast". Lincoln Evening News. September 16, 1903.

- Jose F. Partagas (1997). Year 1903 (PDF). Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 20, 2016.

- ↑ David Levinson (August 20, 2008). 2005 Atlantic Ocean Tropical Cyclones. National Climatic Data Center (Report). Asheville, North Carolina: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 1, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Jose F. Partagas (1997). Year 1903 (PDF). Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 20, 2016.

- ↑ "Violent Hurricane". The Plain Speaker. Fort-de-France, Martinique. August 11, 1903. p. 8. Retrieved May 30, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Renders 5,000 Homeless". Pittsburgh Daily Post. Washington, D.C. August 12, 1903. p. 1. Retrieved May 30, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Maxwell Hall (August 14, 1903). The West Indian Hurricane of August 11, 1903 (PDF). Weather Bureau (Report). Montego Bay, Jamaica: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration; Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. p. 395. Retrieved May 30, 2016.

- 1 2 "Hurricane Spreads Havoc in Jamaica". The New York Times. Kingston, Jamaica. August 13, 1903. p. 1. Retrieved May 30, 2016.

- ↑ "Cuba Escapes Serious Harm". Pittston Gazette. Havana, Cuba. August 13, 1903. Retrieved May 30, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "El Ciclón en Tampico". La Voz de México (in Spanish). Mérida, Yucatán. August 19, 1903. p. 1. Retrieved May 30, 2016.

- ↑ "Storm's Work in Mexico". The New York Times. Austin, Texas. August 22, 1903. Retrieved May 30, 2016.

- 1 2 Edward N. Rappaport; Jose Fernandez-Partagas (April 22, 1997). The Deadliest Atlantic Tropical Cyclones, 1492-1996 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved May 17, 2016.

- ↑ Edward B. Garriott (September 1903). "Forecasts and Warnings" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. 31 (9): 407–408. Bibcode:1903MWRv...31..407G. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1903)31[407b:FAW]2.0.CO;2. Retrieved May 19, 2016.

- ↑ Eliot Kleinberg (2003). Black Cloud: The Deadly Hurricane of 1928. Carroll and Graf Publishing. ISBN 0-7867-1386-0.

- ↑ "East Coast Storm Swept". The Tropical Sun. West Palm Beach, Florida. September 12, 1903. p. 1. Retrieved May 19, 2016.

- 1 2 James Berry (September 1903). "Climate and Crop Service" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. 31 (9): 410. Bibcode:1903MWRv...31..410B. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1903)31[410:CACS]2.0.CO;2. Retrieved May 19, 2016.

- ↑ "Rivers and Floods" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. 31 (9): 409. September 1903. Bibcode:1903MWRv...31V.409.. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1903)31[409f:RAF]2.0.CO;2. Retrieved May 19, 2016.

- ↑ Jay Barnes (2007). Florida's Hurricane History. University of North Carolina Press. pp. 84–85. ISBN 978-0-8078-3068-0. Retrieved May 18, 2016.

- ↑ North Shore WX (2007). "The New Jersey Hurricane of September 16, 1903". Archived from the original on March 6, 2016. Retrieved May 17, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 David M. Roth and Hugh Cobb (July 16, 2001). Early Twentieth Century. Weather Prediction Center (Report). Camp Springs, Maryland: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 21, 2016.

- 1 2 Annual Report of the Operations of the United States Life-Saving Service for the Fiscal Year Ending June 30, 1904. United States Treasury Department. 1904. pp. 96, 180, 384.

- 1 2 3 "Hurricane Sweeps Atlantic Coast". Lincoln Evening News. September 16, 1903.

- ↑ "Shore of Atlantic Swept by Storm". The Daily Northwestern. September 16, 1903.

- ↑ "Storm Sweeps Jersey Coast". Fort Wayne Sentinel. September 16, 1903.

- ↑ "Furious Gale Lashes the City and Harbor". The New York Times. September 17, 1903. Retrieved May 17, 2016.

- ↑ "Mr. Roosevelt's Weather Gale". The Baltimore Morning Herald. September 17, 1903. Retrieved May 20, 2016.

- ↑ Terry Tucker (1982). Beware the Hurricane! The Story of the Cyclonic Tropical Storms That Have Struck Bermuda and the Islanders' Folk-lore Regarding Them (1 ed.). Hamilton, Bermuda: Island Press. p. 261.

- 1 2 Jon Blackwell. "1903: Downpour of destruction". The Trentonian. Retrieved May 28, 2016.

- 1 2 John C. Ensslin (September 3, 2011). "1903 flood still ranks as North Jersey's worst". North Jersey Media Group. Retrieved May 28, 2016.

- ↑ "Houses Swept Away by Floods". Brooklyn Eagle. Easton, Pennsylvania. October 10, 1903. p. 1. Retrieved May 29, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Rain Floods New York". Evening Sentinel. New York City, New York. October 10, 1903. p. 1. Retrieved May 29, 2016.

- ↑ "Two Lives Lost by Landslide". Pittston Gazette. Poughkeepsie, New York. October 10, 1903. p. 1. Retrieved May 29, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

Printed Media

- Terry Tucker. Beware the Hurricane! Hamilton Press: Bermuda, 1966.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to 1903 Atlantic hurricane season. |