1928 New Bedford textile strike

The 1928 New Bedford textile strike was a mass work stoppage of approximately 30,000 machinery operatives in several of the large cotton mills located in New Bedford, Massachusetts, USA. The strike, which ran for several months during the spring and summer of 1928, is remembered for the prominent role played by the Workers (Communist) Party of America in mobilizing the immigrant workers of the region.

The strike began April 16, 1928, over a proposed 10 percent wage cut for factory operatives. Strikers demanded not only the abolition of the planned cut in wages but a 20 percent wage increase and implementation of the 40-hour work week. After considerable controversy control of the strike passed from the Communist-led Textile Mill Committee (TMC) to sundry craft unions affiliated with the American Federation of Labor.

The strike ended in early October when negotiators for the seven non-Communist craft unions representing the strikers accepted the offer of mill owners for a 5 percent wage cut and promises of 30 days' notice before implementation of any further wage reductions. After ratifying the contract over the weekend, strikers defied a last ditch TMC effort to derail the agreement and returned to work on Monday, October 8.

As a radical-led labor stoppage in the American textile industry, the New Bedford strike was the successor to the 1926 Passaic strike and the precursor to the 1929 Gastonia strike, both of which tumultuous events are better remembered to history.

History

Background

During the 19th Century the coastal city of New Bedford, Massachusetts, emerged as the largest whaling port in the world.[1] Some 10,000 seamen shipped from New Bedford to kill and process whales into oil for lighting and machine lubricants and bone for use in corsets.[1] The life was difficult and hard for whaling ship crews but lucrative for shipbuilders, shipowners, and merchants, and the local economy prospered.[1]

The situation began to change in the years after the American Civil War, however, with the profitability of whaling falling dramatically with the discovery and widespread manufacture of kerosene for fuel and petroleum-based machine oil for use as a lubricant.[2] An increased emphasis began being placed on obtaining baleen for corsets, which mandated trips to Arctic waters where baleen whales proliferated.[2] This would end catastrophically in the winter of 1871, when an early return of ice on the ocean trapped and annihilated the entire Arctic fleet, including 32 ships based in New Bedford.[2] A second, smaller catastrophe followed in 1876, resulting in the loss of 12 more ships.[2] By the end of the 1870s prosperous shipbuilders and merchants were looking to leave the dying and unprofitable whaling industry in favor of new forms of capital investment.[2]

Other cities throughout the Northeastern region during the second half of the 19th Century based their local economies upon textile manufacturing, with some 600 mills being scattered across the region by the start of the 1860s.[3] Other lower cost mills dotted the American South, staffed by a labor force willing to accept lesser wages in the wake of a collapsed post-war economy.[3] These mills specialized in low cost, easily produced cotton goods of middling quality, leaving an opening in the marketplace for finely produced cotton textiles.[4] It was to the manufacture of these finer milled goods that New Bedford investors turned when the local economy pivoted from the manufacture of whale oil to fabrics.[5]

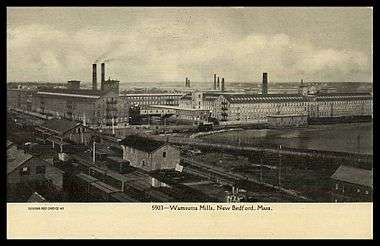

While the Wamsutta Mills, established in 1846, predated the turn of the local economy from whaling to textile making, between 1880 and the coming of World War I the pioneer firm had been joined by another 32 companies, valued at a massive $100 million and employing 30,000 people.[6] The industry prospered and New Bedford boomed in the four decades after 1880, growing in population from 40,000 to more than 120,000.[7]

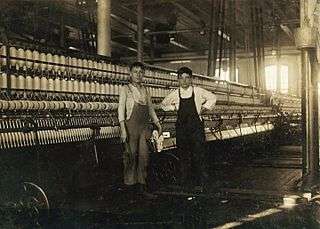

Many of these new arrivals were immigrants — English, Irish, and Germans with prior experience in the milling industry, followed later by French-Canadians, Poles, Syrians, and Portuguese (including the descendants of former slaves from the Portuguese colonies of the Azores and Cabo Verde).[8] Very few American blacks worked in the mills of New Bedford, with one 1900 survey counting just 25 out of a population of just over 11,000 factory workers.[8] These workers lived in densely populated neighborhoods at the north and south of the city, with the owning and financial class living in the prosperous city center.[9]

Wage cut and work stoppage

During the middle years of the 1920s, competitive pressure in the era of post-World War I deflation kept wages of factory operatives unusually low, with the Massachusetts Department of Labor reporting average weekly wages for New Bedford textile workers of $19.95.[10] Things deteriorated further during the first three months of 1928, with that same governmental body making note of a further weekly wage fall to just $19.00.[10]

Local employers, feeling the pressure of modern factories in the low-wage South sought further wage reductions in an effort to remain competitive.[11] In April 1928 united action was enacted by the New Bedford Cotton Manufacturers' Association in unilaterally slashing wages a further 10 percent across the board.[11] This cut was met by the collective action of the New Bedford Textile Council,[11] which approved a work stoppage slated to begin on Monday, April 16, 1928 by a vote of 2,571 to 188.[12] The job stoppage in protest of the proposed 10 percent cut in wages to affect almost all of the 30,000 workers employed in the cotton, rayon, and woolen mills of New Bedford.[12]

Seven craft unions directly represented about 8,000 of New Bedford's textile workers.[11] These included locals of the American Federation of Textile Operatives, an independent organization.[11] The deteriorating wage situation spurred militance in many of these locals, however, and in April and May 1928 a move was made to join the United Textile Workers (UTW), a larger and more potent labor organization affiliated with the American Federation of Labor (AFL).[11]

Most of the minority of New Bedford workers who were unionized ahead of the 1928 strike were from the highly skilled trades — loom fixers, weavers, warp twisters, and the like — who were generally native-born and English-speaking.[11] Those unorganized were more often than not unskilled or low skilled immigrants, forced to perform the dirtiest and most monotonous jobs and barred by union protection by the rigid craft structure of the New Bedford union movement.[11]

Development

Resolution

Legacy

See also

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 Daniel Georgianna with Roberta Hazen Aaronson, The Strike of '28. New Bedford, MA: Spinner Publications, 1993; pg. 12.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Georgianna and Aaronson, The Strike of '28, pg. 13.

- 1 2 Georgianna and Aaronson, The Strike of '28, pg. 19.

- ↑ Georgianna and Aaronson, The Strike of '28, pp. 19-20.

- ↑ Georgianna and Aaronson, The Strike of '28, pg. 20.

- ↑ Georgianna and Aaronson, The Strike of '28, pg. 21.

- ↑ Georgianna and Aaronson, The Strike of '28, pg. 22.

- 1 2 Georgianna and Aaronson, The Strike of '28, pg. 22.

- ↑ Georgianna and Aaronson, The Strike of '28, pg. 24.

- 1 2 Philip S. Foner, History of the Labor Movement in the United States: Volume 10: The TUEL, 1925-1929. New York: International Publishers, 1994; pg. 164.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Foner, History of the Labor Movement in the United States: Volume 10, pg. 165.

- 1 2 Associated Press, "Textile Workers Strike Monday," Fitchburg [MA] Sentinel, April 13, 1928, pg. 25.

Further reading

- Fred Beal, Proletarian Journey: New England, Gastonia, Moscow. New York: Hillman, Curl, 1937.

- Judith A. Boss and Joseph D. Thomas, New Bedford: A Pictorial History. Norfolk, VA: Donning Co. Publishers, 1983.

- Paul Blanchard, "New Bedford Goes on Strike," New Republic, May 23, 1928.

- Robert W. Dunn and Jack Hardy, Labor and Textiles: A Study of Cotton and Wool Manufacturing. New York: International Publishers, 1931.

- Philip S. Foner, History of the Labor Movement in the United States: Volume 10: The TUEL, 1925-1929. New York: International Publishers, 1994.

- Philip S. Foner, Women and the American Labor Movement. New York: The Free Press, 1979.

- Daniel Georgianna with Roberta Hazen Aaronson, The Strike of '28. New Bedford, MA: Spinner Publications, 1993.

- Robert Morss Lovett, " New Bedford's Strike: A Knockout or a Comeback?" New Republic, Sept. 12, 1928.

- David Lee McMullen, Strike: The Radical Insurrections of Ellen Dawson. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2010.

- Michael W. Santos, "Community and Communism: The 1928 New Bedford Textile Strike," Labor History, vol. 26 (1985), pp. 230-249.

- David Saposs, Left Wing Unionism. New York: International Publishers, 1926.

- Seymour Louis Wolfbein, The Decline of a Cotton Textile City: A Study of New Bedford. New York: Columbia University Press, 1944.

External links

- Joe Silva, "New Bedford's Forgotten History," NewBedfordGuide.com/ April 4, 2013.