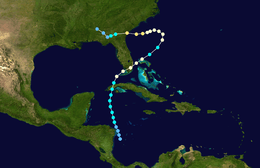

1947 Atlantic hurricane season

| |

| Season summary map | |

| First system formed | July 31, 1947 |

|---|---|

| Last system dissipated | October 22, 1947 |

| Strongest storm1 | "Fort Lauderdale (George)" – 938 mbar (hPa) (27.7 inHg), 145 mph (230 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| Total storms | 10 |

| Hurricanes | 5 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 2 |

| Total fatalities | 94 |

| Total damage | $135.3 million (1947 USD) |

| 1Strongest storm is determined by lowest pressure | |

1945, 1946, 1947, 1948, 1949 | |

The 1947 Atlantic hurricane season was the first Atlantic hurricane season to have significant tropical cyclones named by the United States Air Force.[1]

The 1947 hurricane season was a fairly active one in terms of landfalling storms. A Category 2 hurricane hit near Tampico, a Category 1 hit near Galveston, and a Category 2 hit near the Georgia/South Carolina border. The most intense and damaging storm struck Fort Lauderdale as a Category 4 hurricane, then made a second landfall in Louisiana as a high-end Category 2 hurricane.[2]

Storms

Tropical Storm One

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | July 31 – August 2 | ||

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min) ≤ 1001 mbar (hPa) | ||

A low pressure area in the Bay of Campeche developed into a tropical depression at 06:00 UTC on July 31.[3][2] Moving north-northwestward, the depression deepened into a tropical storm six hours later. The storm then intensified slowly and gradually curved to the northwest. At 00:00 UTC on August 2, the storm attained its peak intensity with maximum sustained winds of 50 mph (85 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 1,001 mbar (29.6 inHg).[2] The latter was observed at Port Isabel, Texas, while the former was estimated based on the pressure-wind relationship.[3] Simultaneously, the cyclone made landfall in Tamaulipas about 25 mi (40 km) south of the Mexico–United States border. The system weakened to a tropical depression by 12:00 UTC on August 2 and dissipated near Reynosa shortly thereafter.[2]

Small craft were advised between the lower and middle coast of Texas were advised to remain in port.[4] The American Red Cross recommended that residents of Port Aransas evacuate as a precaution, but mainly only tourists in the area fled.[5] Record Most of the damage was done to cotton crops, due to heavy rainfall, with up to 9.35 in (237 mm) observed at Raymondville.[6] However, the precipitation was more beneficial than damaging. The storm caused just over $2 million in damage.[7]

Hurricane Two

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | August 9 – August 16 | ||

| Peak intensity | 110 mph (175 km/h) (1-min) ≤ 977 mbar (hPa) | ||

A tropical depression developed about 125 mi (200 km) north-northwest of Barranquilla, Colombia, early on August 9. The depression moved northwestward across the Caribbean Sea and remained weak for a few days, before reaching tropical storm status on 00:00 UTC on August 12. About 16 hours later, the cyclone made landfall near Punta Allen, Quintana Roo, with winds of 50 mph (80 km/h). After entering the Bay of Campeche on August 13, the system resumed strengthening, becoming a hurricane early on August 14. Later that day, the cyclone peaked as a Category 2 hurricane on the modern day Saffir–Simpson scale with maximum sustained winds of 110 mph (175 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 977 mbar (28.9 inHg),[2] both of which were observed by during a reconnaissance aircraft flight.[3] On August 15, the system curved southwestward and made landfall near Tampico, Tamaulipas, around 10:00 UTC, at the same intensity. The storm rapidly weakened after moving inland and dissipated by 06:00 UTC on August 16.[2]

On August 9, a tropical depression formed in the Caribbean Sea. It moved west-northwest, strengthening into a tropical storm before hitting near Cozumel, Mexico, on August 12 with winds of .[2] As it moved through the Bay of Campeche, it quickly strengthened into a Category 2 hurricane and hit just south of Tampico on August 15. The hurricane dissipated the next day over land, causing 19 fatalities.

Hurricane Three

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | August 18 – August 27 | ||

| Peak intensity | 80 mph (130 km/h) (1-min) 984 mbar (hPa) | ||

A tropical depression became a tropical storm over the Florida Straits on August 19. It headed west-northward, intensifying to a first peak of 50 mph (80 km/h) before weakening on August 20. Two days later, the storm hit near Golden Meadow, Louisiana, as a weak tropical storm, but soon turned around and headed back into the Gulf of Mexico. It then turned back toward the coast and steadily strengthened into a minimal hurricane before making landfall near Galveston, Texas, on August 24.[2] The hurricane resulted in $200,000 in damage, as well as one death. It also produced a 3.6-foot (1.1 m) storm surge as it passed offshore of Grand Isle, Louisiana, on August 22.

Hurricane Four (George)

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | September 4 – September 21 (Extratropical on September 21) | ||

| Peak intensity | 145 mph (230 km/h) (1-min) 938 mbar (hPa) | ||

A tropical wave developed into a tropical depression about 175 mi (280 km) east-southeast of Dakar, Senegal, early on September 4.[7][2] Several hours later, the depression strengthened into a tropical storm,[2] which was named George by the United States Air Force in real time.[8] After moving generally westward for several days, the storm failed to intensify significantly and turned northwestward on September 10. By the following day, George finally became a Category 1 hurricane. The storm intensified further over the next few days and later peaked as a Category 4 hurricane with maximum sustained winds of 145 mph (230 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 938 mbar (27.7 inHg). Early on September 16, George weakened to a Category 3 and curved westward while approaching the northern Bahamas. At 19:00 UTC, the hurricane struck the Abaco Islands with winds of 120 mph (195 km/h).[2] In the Bahamas, the storm produced a large storm surge and strong winds, damaging or destroying many homes and docks on the western end of Grand Bahama.[9]

Thereafter, George continued westward and re-intensified into a Category 4 at 12:00 UTC on September 17, just three and a half hours before the storm made landfall near Fort Lauderdale, Florida, with winds of 130 mph (210 km/h).[2] In Florida, advance warnings and stringent building codes were credited with minimizing structural damage and reducing loss of life to 17 people, but nevertheless widespread flooding and coastal damage resulted from heavy rainfall and high tides.[10] Many vegetable plantings, citrus groves,[11] and cattle were submerged or drowned as the storm exacerbated already high water levels and briefly threatened to breach the dikes surrounding Lake Okeechobee.[12] However, the dikes held firm, and evacuations were otherwise credited with minimizing the potential death toll.[13] On the west coast of the state, the storm caused further flooding, extensive damage south of the Tampa Bay area, and the loss of the Cuban fishing vessel Antonio Cerdado offshore Fort Myers, resulting in seven deaths.[7] Damage in Florida reached $31.8 million.[14]

On September 18, the hurricane entered the Gulf of Mexico and threatened the Florida Panhandle. Later, George made landfall southeast of New Orleans, Louisiana, on September 19 as a strong Category 2 with winds of 110 mph (175 km/h). George weakened to a tropical storm later that day, and then a tropical depression on September 20.[2] The cyclone was absorbed by a cold front over Missouri on the following day.[3] Strong winds in the vicinity of Lake Pontchartrain caused water to over-top the levees, leaving some lakefront streets inundated "waist-deep" and many areas of the city under about 2 ft (0.61 m) of water.[15][16] New Orleans alone suffered about $100 million in damage.[17] The widespread flooding spurred flood-protection legislation and the creation of an enlarged levee system to safeguard the flood-prone area.[18] Some coastal flooding also occurred in Mississippi. The state suffered slightly more than $28.4 million in damage.[14] The storm destroyed 1,647 homes and structurally impacted 25,000 others in both Louisiana and Mississippi.[7] Throughout its path, the hurricane caused $160.2 million in damage and 51 casualties.[10][14][17]

Tropical Storm Five

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | September 7 – September 9 | ||

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min) ≤ 1006 mbar (hPa) | ||

At 00:00 UTC on September 7, a low pressure area developed into a tropical depression about 135 mi (215 km) south-southwest of Cape St. George Island, Florida.[2][3] The depression moved northward and intensified, reaching tropical storm status about 18 hours later. Around that time, the cyclone curved north-northwestward. Early on September 8, the storm peaked with maximum sustained winds of 60 mph (95 km/h),[2] which was observed by a ship. Between 07:00 and 10:00 UTC, an observation station in Mobile, Alabama, recorded a barometric pressure of 1,006 mbar (29.7 inHg), the lowest known in association with the cyclone.[3] At 14:00 UTC on September 8, the storm made landfall on Dauphin Island, Alabama, and later near Bayou La Batre. By early the next day, the system weakened to a tropical depression and dissipated over southern Mississippi shortly thereafter.[2]

Some coastal areas reported strong wind gusts, including 45 mph (72 km/h) in Mobile, Alabama, and 51 mph (82 km/h) in Pensacola, Florida. At Mobile Bay, two ships were beached, but were re-floated later that day. Overall, damage from the storm was minimal.[3]

Tropical Storm Six

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | September 20 – September 26 (Extratropical on September 24) | ||

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min) 987 mbar (hPa) | ||

A tropical wave developed into a tropical storm over western Jamaica on September 20. It headed northwestward, hitting Cuba on September 22 with winds of 50 mph (80 km/h). The storm turned north-northeastward over the Gulf of Mexico, strengthening into a strong tropical storm before hitting near Cedar Key on September 23.[2] The storm became extratropical early the next day, after causing tornadic activity amounting to $100,000 in damage (1947 US dollars).

Tropical Storm Seven

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | October 4 – October 9 | ||

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min) ≤ 1000 mbar (hPa) | ||

On October 6, a wave formed into a tropical storm (possibly a subtropical storm) over the Bahamas. It moved rapidly north-northwestward, and hit near Brunswick, Georgia, on October 7. It looped over Georgia and Florida, and dissipated on October 9.[2]

Tropical Storm Eight

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | October 8 – October 11 | ||

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min) ≤ 1001 mbar (hPa) | ||

A low pressure area detached from a cold front and developed into a tropical depression on October 8, about 710 mi (1,140 km) southwest of Flores Island in the Azores. Moving slowly northeastward, the cyclone strengthened, despite relatively cool air and sea surface temperatures,[3] with sustained winds reaching 60 mph (95 km/h) later that day. Early on October 9, the system curved east-northeastward. The following day, a ship observed a barometric pressure of 1,001 mbar (29.6 inHg), the lowest pressure associated with the storm.[2] By early on October 11, the system was absorbed by an extratropical cyclone about 150 mi (240 km) west-southwest of Flores Island.[2][3]

Hurricane Nine (King)

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | October 8 – October 16 | ||

| Peak intensity | 105 mph (165 km/h) (1-min) 965 mbar (hPa) | ||

A tropical low was detected off the coast of Nicaragua on October 8. The low then drifted northward where it became a tropical storm the next day. The tropical storm then passed over the western tip of Cuba, producing a peak wind gust of 57 mph (92 km/h). The storm strengthened over the southeastern Gulf of Mexico to attain hurricane status on October 11, and after brushing the Florida Keys before making landfall near Cape Sable, Florida, on October 12 with winds of 90 mph (140 km/h) and a central pressure of about 975 mb (28.79 inHg). The hurricane moved offshore near Pompano Beach and later turned back to the west, toward the Southeastern United States. The storm strengthened as it turned to the west, and on October 15, the hurricane made its final landfall near the Georgia–South Carolina state line as a Category 2 hurricane.[2] The storm was unofficially known as Hurricane King.[19] The hurricane was noted for the first time hurricane seeding was conducted in the Atlantic basin by the United States Weather Bureau through an operation called Project Cirrus. A Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress dropped 80 lb (36 kg) of dry ice onto the storm from 500 ft (150 m) above its cloudtop after it had moved 350 mi (560 km) off Jacksonville, Florida. Shortly afterward, the storm reversed course and headed for Savannah. The scientists conducting the experiment believed they had caused this change, but it was shown a 1906 hurricane had followed a similar pattern.[20]

An airport in south Florida recorded peak winds of 80 mph (130 km/h). The hurricane dropped 5–13 in (130–330 mm) of rain across central and southern part of the state, including in Hialeah where the storm produced 3.6 in (91 mm) in a one-hour period and over 6 in (150 mm) in a 75 minute period. The flooding rains left many neighborhoods in up to six feet of water due to a previously wet summer, and left over 2,000 Miami-Dade County residents homeless. The flooding also closed Route 1 from Miami to Fort Lauderdale, as well as a highway to Everglades City. The hurricane spawned a tornado in both Coral Gables and Miami, one of which destroyed three warehouses. In all, the hurricane caused $27.5 million in damage in Florida. Following the passage of the hurricane, Hialeah mayor Henry Milander declared a state of emergency and restricted access to the city. In Miami, many residents had to use boats and rafts to survey damage and look for survivors, due to the flooding. Winds in Georgia peaked at 85 mph (135 km/h) in Savannah, where the storm caused $20 million in damage. Elsewhere in the state, the storm caused $500,000 in damage, mainly due to a tornado that touched down near Hinesville. Tides 12 ft (3.7 m) above normal were reported from Georgia to South Carolina. The high tides in Charleston, South Carolina, caused minor beach erosion and isolated street flooding, and one person was killed there by a falling tree. In North Carolina, the high tides caused minor flooding.[19]

Hurricane Ten (Love)

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | October 17 – October 22 | ||

| Peak intensity | 120 mph (195 km/h) (1-min) 961 mbar (hPa) | ||

This storm developed on October 17 over the Leeward Islands as a tropical storm. It moved northwest, bypassing Puerto Rico and strengthening to hurricane status while beginning a gradual curve to the northeast. Hurricane Love was the first storm flown at low-levels by the 53d Weather Reconnaissance Squadron.[21] The storm reached its peak intensity as a Category 3 hurricane just west of Bermuda, bringing winds estimated at 100 mph (175 km/h) to the island. The storm continued northeast and became extratropical on October 22.[2]

Season effects

| Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale | ||||||

| TD | TS | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 |

| Storm name |

Dates active | Storm category

at peak intensity |

Max 1-min wind mph (km/h) |

Min. press. (mbar) |

Areas affected | Damage (millions USD) |

Deaths | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | June 13 – 14 | Tropical depression | N/A | 1003 | Mexico | None | 0 | |||

| One | July 31 – August 2 | Tropical storm | 50 (85) | 1001 | Mexico, Texas | 2 | 0 | |||

| Two | August 9 – 16 | Category 2 hurricane | 110 (175) | 977 | Mexico | Unknown | 19 | |||

| Three | August 18 – 27 | Category 1 hurricane | 80 (130) | 984 | Cuba, United States Gulf Coast | 0.2 | 0 | |||

| Depression | September 1 – 2 | Tropical depression | N/A | N/A | None | None | 0 | |||

| Four | September 4 – 20 | Category 4 hurricane | 145 (230) | 938 | Bahamas, United States Gulf Coast | 110 | 51 | |||

| Five | September 7 – 8 | Tropical storm | 60 (95) | N/A | United States Gulf Coast | None | 0 | |||

| Depression | September 15 – 30 | Tropical depression | N/A | N/A | None | None | 0 | |||

| Six | September 20 – 24 | Tropical storm | 65 (100) | 985 | Cuba, United States Gulf Coast | 0.1 | 0 | |||

| Seven | October 4 – 9 | Tropical storm | 60 (95) | 1000 | Florida, Georgia | None | 0 | |||

| Eight | October 8 – 11 | Tropical storm | 60 (95) | 1001 | None | None | 0 | |||

| Nine | October 8 – 16 | Category 2 hurricane | 105 (165) | 965 | None | 3.26 | 1 | |||

| Ten | October 17 – 22 | Category 3 hurricane | 120 (195) | 961 | Bermuda | None | 0 | |||

| Depression | October 25 – 26 | Tropical depression | N/A | N/A | None | None | 0 | |||

| Depression | November 28 – December 1 | Tropical depression | N/A | N/A | Lesser Antilles, Dominican Republic | None | 0 | |||

| Season Aggregates | ||||||||||

| 15 cyclones | July 31 – December 1 | 145 (230) | 938 | 112.3 | 70 | |||||

See also

References

- ↑ Dorst, Neal (October 23, 1947). "They Called the Wind Mahina: The History of Naming Cyclones". Hurricane Research Division, Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. p. Slide 49.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 National Hurricane Center; Hurricane Research Division (July 6, 2016). "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)". United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved December 5, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Christopher W. Landsea; et al. Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT. Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved January 11, 2016.

- ↑ "Gulf Area Fears Tropical Storm". Pampa News. Brownsville, Texas. Associated Press. August 1, 1947. p. 1. Retrieved January 21, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Tropical Storm is Diminishing". The Vernon Daily Record. Associated Press. August 2, 1947. Retrieved January 21, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Crops Damaged in Gulf Storm". Lubbock Avalanche-Journal. Associated Press. August 3, 1947. Retrieved January 21, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 3 4 1947 Monthly Weather Review

- ↑ David M. Roth (2010-01-13). Louisiana Hurricane History (PDF). National Weather Service Southern Region Headquarters. p. 36. Retrieved 2011-01-25.

- ↑ "Assess Atlantic Hurricane Damage". Lethbridge Herald. September 18, 1947.

- 1 2 Jay Barnes (2007). Florida's Hurricane History. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. p. 173. ISBN 1469600218. Retrieved January 12, 2016.

- ↑ "Glades Towns In Flood Path". Palm Beach Post. September 21, 1947. pp. 1, 12.

- ↑ "Broward County Takes Stock of Storm Damage". Fort Lauderdale Daily News. September 22, 1947. p. 12.

- ↑ Will, Lawrence E. (1978). Okeechobee Hurricane and the Hoover Dike. Great Outdoors Publishing. ASIN B0006YT5ZG.

- 1 2 3 "Severe Local Storms for September 1947" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. U.S. Weather Bureau. 75 (11): 183–84. September 1947. Bibcode:1947MWRv...75..183.. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1947)075<0183:SLSFS>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved 19 July 2012.

- ↑ "Hurricane Hits New Orleans". Windsor Daily Star (Ontario, Dominion of Canada). September 19, 1947. pp. 1–2.

- ↑ Joel K. Bourne, Jr. (October 2004). "Gone With the Water". National Geographic. 206 (4): 88–105.

- 1 2 David M. Roth (2010). Louisiana Hurricane History. National Weather Service (Report). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 5, 2008. Retrieved July 10, 2012.

- ↑ Craig C. Colten (2009). Perilous Place, Powerful Storms: Hurricane Protection in Coastal Louisiana. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 9781604733457.

- 1 2 Barnes, Jay Florida's Hurricane History', University of North Carolina Press (1998), ISBN 0-8078-4748-8, 174 -180

- ↑ Whipple, A.B.C. (1982). Storm. Time-Life Books. ISBN 0-8094-4312-0.

- ↑ Tom Robison (April 2000). "The B-29 in Weather Reconnaissance". Air Weather Reconnaissance Association. Retrieved 2011-01-25.