1st Armored Division (United States)

| 1st Armored Division | |

|---|---|

1st Armored Division distinctive unit insignia | |

| Active |

1940–1946 1951–present |

| Country |

|

| Branch |

|

| Type | Combined arms (armor and mechanized infantry) and Stryker infantry |

| Role | Command and control organization containing two to four maneuver brigades |

| Size | Division |

| Part of | III Corps |

| Nickname(s) | "Old Ironsides"[1] |

| Motto(s) | Iron Soldiers! |

| March | Iron Soldier March |

| Engagements | Iraq War |

| Commanders | |

| Commander | Maj. Gen. Robert P. White |

| Notable commanders |

Orlando Ward Ernest N. Harmon |

| U.S. Armored Divisions | |

|---|---|

| Previous | Next |

| 2nd Armored Division (Inactive) | |

The 1st Armored Division—nicknamed "Old Ironsides"[1]—is a combined arms division of the United States Army. The division is part of III Corps, with its base of operations in Fort Bliss in El Paso, Texas. It was the first armored division of the U.S. Army to see battle in World War II.

Major General Robert P. White assumed command of the 1st Armored Division on 15 June 2016.[2]

The division command group consists of:

- Commanding General: Major General Robert P. White

- Deputy Commanding General (Operations): Brigadier general Frazer Lawrence.[3]

- Deputy Commanding General (Support): Brigadier general Jeffery Broadwater.[4]

- Deputy Commanding General (Maneuver): Brigadier general Daniel Walrath.[5]

- Chief of Staff: Colonel Charles D. Costanza.[6]

- Command Sergeant Major: Command Sergeant Major Danny Day.[7]

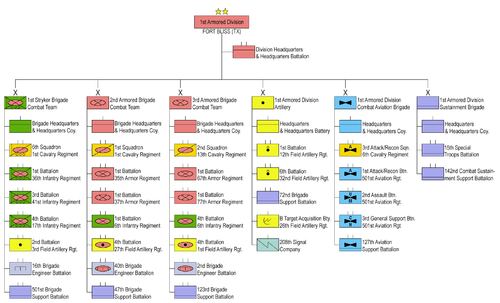

Current structure

Since relocating to Fort Bliss, Texas, the division has been reorganized under the new modular design, in which the deployable unit of maneuver is a brigade, rather than a division. The division consists of three brigade combat teams (BCTs), a combat aviation brigade (CAB), a division artillery brigade,[8] and a sustainment brigade.

After the spring of 2015, 3rd IBCT deactivated after redeploying from Afghanistan, and its maneuver battalions joined the remaining three BCTs; 4th ABCT has reflagged as 3rd BCT.[9]

1st Armored Division consists of the following elements:

- Division Headquarters and Headquarters Battalion "Gladiator"

- Headquarters and Support Company

- Operations Company

- Intelligence and Sustainment Company

- Division Signal Company

- 1st AD Band

- 1st Stryker Brigade Combat Team "Ready First"[10]

- Brigade Headquarters and Headquarters Company

- 6th Squadron, 1st Cavalry Regiment

- 4th Battalion 17th Infantry Regiment

- 1st Battalion 36th Infantry Regiment

- 3rd Battalion 41st Infantry Regiment

- 2nd Battalion 3rd Field Artillery Regiment

- 16th Brigade Engineer Battalion

- 501st Brigade Support Battalion

- 2nd Armored Brigade Combat Team "Iron Brigade"[1][11]

- Brigade Headquarters and Headquarters Company

- 1st Squadron 1st Cavalry Regiment

- 1st Battalion 35th Armored Regiment

- 1st Battalion 37th Armor Regiment

- 1st Battalion, 6th Infantry Regiment

- 4th Battalion, 27th Field Artillery Regiment

- 40th Brigade Engineer Battalion

- 47th Brigade Support Battalion

- 3rd Armored Brigade Combat Team, "Bulldogs"[12]

- Brigade Headquarters and Headquarters Company

- 2nd Squadron, 13th Cavalry Regiment

- 1st Battalion, 67th Armor Regiment

- 1st Battalion, 77th Armor Regiment

- 4th Battalion, 6th Infantry Regiment

- 4th Battalion, 1st Field Artillery Regiment[9]

- 2nd Brigade Engineer Battalion(June.2015,raised from the Brigade's former Special Troops Battalion)

- 123rd Brigade Support Battalion

- 1st Armored Division Artillery "Iron Steel" (formerly 212th Fires Brigade)[13][14]

- Headquarters & Headquarters Battery

- 24th Press Camp Headquarters

- Combat Aviation Brigade, 1st Armored Division "Iron Eagle"

- Headquarters and Headquarters Company

- 3rd (Heavy Attack-Reconnaissance) Squadron, 6th Cavalry Regiment "Heavy Cav"[15][16][17]

- 1st Attack Battalion, 501st Aviation Regiment "Pistoleros"

- 2nd General Aviation Battalion, 501st Aviation Regiment "Desert Knights"

- 3rd Assault Battalion, 501st Aviation Regiment "Apocalypse"

- 127th Aviation Support Battalion "Work Horse"

- 1st Armored Division Sustainment Brigade[18]

- Headquarters and Headquarters Company

- 15th Special Troops Battalion

- 142nd Combat Sustainment Support Battalion

Insignia

The division was nicknamed "Old Ironsides", by its first commander, Major General Bruce R. Magruder, after he saw a picture of the frigate USS Constitution, which is also nicknamed "Old Ironsides". The large "1" at the top represents the numerical designation of the division, and the insignia is used as a basis for most other sub-unit insignias.

In January, 1918, the Tank Corps of the United States Army was created with Colonel S.D. Rockenback as its chief. At his direction, a Lt. Wharton designed the original coat of arms which was a triangle on a shield with a surrounding wreath and a dragon in silver. The triangle itself is an old heraldic element of armorial design known as a pile [the head of a spear]. There was no shoulder patch in 1918, only this unit crest.

The 7th Cavalry Brigade (mechanized) contributed the other part of the present day Armor shoulder patch. The brigade formed out of the 1st Cavalry Regiment at Marfa Texas, on Jan 16, 1933 under General Van Voohris, then Colonel of the Cavalry. The 7th Cav Bde included the 13th Cavalry. The 7th Cavalry Brigade had been organized specifically to develop the new armored force concept and train in the emerging tactics of modern war-fighting.

Colonel George Linthwaite (then a newly enlisted Private) joined the 13th Cavalry regiment in 1933. Major General Robert W. Grow (then a Major and brigade adjutant) was instructed to develop a shoulder patch for the new armored force. Major Grow announced to the brigade that a contest would be held to design the new Armored force patch. A three-day pass was to be the reward for the designer of the winning entry.

Private Linthwaite designed a patch which was 4” round and had a solid yellow-gold background to symbolize the Cavalry heritage. On the face of the patch he drew a stylized black tank track with drive and idler sprockets to symbolize mobility. In the center of the track at a slight diagonal, he placed a single cannon barrel, also in black, to symbolize fire power. Finally, to symbolize the striking power of the new armored force, he added a diagonal lightning bolt in red, extending across the total design and full diameter of the patch. Private Linthwaite won his pass.

In 1940, Major General Chaffee was made head of the newly created Armor Forces which had evolved from the old 7th Cav Brigade and were preparing for the looming war in Europe. Gen Chaffee wanted a patch for this new Armored Force. He chose to combine the 7th Brigade patch with the triangle from the World War I crest. The tri-colors, with blue for infantry, red for artillery, and yellow for cavalry – represented the three basic components of the mechanized Armor force. In 1940 the War Department officially designated the now familiar patch worn by soldiers of all United States Army Armored Divisions.[19]

Origins

Col. Daniel Van Voorhis took a cadre of 175 officers and enlisted men from Fort Eustis to Fort Knox in February 1932, and established a Provisional Armored Car Platoon. This was based on an earlier effort, but was predicated on a new Cavalry Regiment TO&E (Table of Organization and Equipment) which was published that year. Also published, but never implemented, was a cavalry division TO&E which reflected the then unnatural assimilation of machines into the Horse Cavalry. Van Voorhis's cadre and platoon became the kernel for the 7th Cavalry Brigade, which went active on 1 March 1932 at Fort Knox. At first, it was nothing more than a headquarters detachment and the Armored Car Platoon.

On 3 January 1933, the 1st Cavalry Regiment was relieved from assignment to the 1st Cavalry Division, and was moved from Fort D.A. Russell (now Francis E. Warren Air Force Base) to Fort Knox. The earlier Mechanized Platoon was incorporated into the new regimental TO&E, and the result was the 1st Cavalry Regiment [Mechanized], which went active on 16 January 1933. The new regimental commander was Colonel Van Voorhis, late of the experimental Mechanized Force, while the executive officer was Adna Chaffee. The Post Commander of Fort Knox was Brigadier General Julian R. Lindsey, another cavalryman. To round out the cavalry nature of the unit, Major Robert W. Grow was on the regimental staff.

Van Voorhis added the 13th Cavalry Regiment, the 68th Field Artillery Battalion, the 7th Reconnaissance Squadron, the 7th Signal Troop, the 4th Medical Troop, the 47th Engineer Troop and the 17th Quartermaster Battalion. The 7th Cavalry Brigade was fully formed. Van Voorhis remained in command until September 1938, when he was promoted to command the V Corps (United States) at Indianapolis, Indiana. Chaffee took over from Van Voorhis.

On 7 May 1940, the 7th Cavalry Brigade took part in the Louisiana Maneuvers at Monroe, Louisiana that were instrumental in developing the armored division concept. The maneuvers concluded on 27 May 1940, and the brigade returned to Fort Knox on 31 May 1940, and preparations began to expand the brigade into a tank division.

After the brutal trench warfare of World War I, the United States was looking for new ways to engage in armed conflict. As the German Army invaded France, Belgium, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands, the United States military hierarchy realized that an armored division was essential for a modern army. While training outside of Alexandria, Louisiana, the commanders of the 7th Cavalry Brigade met in a high school basement to discuss the creation of an American armored division. Major General Frank M. Andrews, Generals Adna R. Chaffee and Bruce Magruder, and Colonel George S. Patton Jr. agreed to recommend to Washington that the U.S. Army establish its first tank division.[20]

On 10 July 1940, in a conference with the Chief of Staff of the Army, the U.S. Army founded an Armored Force. Two weeks later General Adna R. Chaffee was given the order to head the creation of America's first tank division.

Birth

On July 15, 1940, the 1st Armored Division, largely an expanded and reorganized version of the 7th Cavalry Brigade, was activated at Fort Knox under the command of Major General Bruce Magruder. The 1st Cavalry Regiment was redesignated as 1st Armored Regiment and 13th Cavalry Regiment was redesignated as 13th Armored Regiment under the 1st Armored Brigade, 1st Armored Division.[20] For more than two years after its activation, the 1st Armored Division trained at Fort Knox and the division pioneered and developed tank gunnery and strategic armored offensives while increasing from 66 medium-sized tanks to over 600 medium and light armored vehicles.[20]

Order of battle

The first order of battle for the 1st Armored Division was:

- HHC, 1st Armored Division

- HHC, 1st Armored Brigade

- 1st Armored Regiment (Light)

- 13th Armored Regiment (Light)

- 69th Armored Regiment (Medium)

- 68th Armored Field Artillery Regiment

- 6th Armored Infantry Regiment

- 27th Field Artillery Battalion (Armored)

- 16th Engineer Battalion (Armored)

- 81st Armored Reconnaissance Squadron

- 13th Quartermaster Battalion (Armored)

- 19th Ordnance Battalion (Armored)

- 47th Medical Battalion (Armored)

- 141st Signal Company (Armored)

- HHC, 1st Armored Brigade

On 15 April 1941 the 1st AD sent a cadre to form the U.S. 4th Armored Division ("Name Enough") at Pine Camp, New York.

World War II

Commanders

- MG Bruce Magruder (July 1940 – March 1942),[21]

- MG Orlando Ward (March 1942 – April 1943),

- MG Ernest N. Harmon (April 1943 – July 1944),

- MG Vernon Prichard (July 1944 – September 1945),

- MG Roderick R. Allen (September 1945 – January 1946),

- MG Hobart R. Gay (February 1946 to inactivation).

Training

The division was trained at Fort Knox, Kentucky, July 15, 1940. It was an experiment in a self-supporting, permanent fighting unit with tanks as the nucleus. This experiment in a self-sustaining blitzkrieg force had never been tried before, and the troops necessary for such an organization were drawn from many army posts.

When the organization was completed, the division had tanks, artillery and infantry in strength. In direct support were tank destroyer, maintenance, medical, supply and engineer battalions. But bringing the division up to its full quota of tanks, guns and vehicles was difficult. Although new equipment was received almost daily, the division had until March 1941, only nine ancient medium tanks. Principal armament of the nine was a 37-millimeter gun.

Fort Knox in 1940 was not unlike other army posts in the nation. There were a few minor differences—the high-crowned overseas cap was worn on the left side of the head, and the few experimental models of the quarter-ton truck that were then on the post were called "peeps" to distinguish them from the command car which had always been called a "jeep" by armored men.

To become expert with their newly acquired tanks, half-tracks and guns, most of the division attended the Armored Force School at Knox. The students stood reveille at 4 a.m., sat at attention during class and at 4 p.m. rushed to the nearest post exchange for a bottle of beer, which helped counteract the hot summer weather.

Every day, some unit attacked from the steel observation tower called 'O.P. Six' to capture some part of a 25 square mile patch of Kentucky brush and gullies. The troops made three-day road marches, scraped and polished their vehicles for Saturday morning inspections, sweated out the lines at the bus station and occasionally dropped by Benny's or Big Nell's, the most easily accessible civilian nightspots.

With more than a year's training behind them, the division left in September 1941, for three month's maneuvers in Louisiana. The day before Pearl Harbor, the division was back at Fort Knox. The draftees had proved themselves as soldiers in the maneuvers. They looked forward to discharges after their year's service. The regular army men expected furloughs.

Training took on a new intensity. The division was reorganized, and all tanks, both medium and light were put into two armored regiments, the 1st and 13th. A third armored field artillery battalion, the 91st, was formed, and the 701st Tank Destroyer Battalion was organized and attached to the division.

At Fort Knox, the division participated in the Technicolor short movie The Tanks Are Coming (as the "First Armored Force"). It deployed to participate in the VII Corps Maneuvers on 18 August 1941. Once the maneuvers concluded, 1st Armored Division then moved on 28 August 1941, and arrived at Camp Polk for the Second Army Louisiana Maneuvers on 1 September 1941. They then moved to Fort Jackson on 30 October 1941 to participate in the First Army Carolina Maneuvers. 1st AD then returned to Fort Knox on 7 December 1941, but started to prepare for deployment overseas instead of returning to garrison.

A few months later, in March 1942, the division was en route to the Fort Dix, New Jersey, staging area under command of Major General Orlando Ward. General Ward relieved Major General Bruce R. Magruder, who had commanded the division since its organization. It was a "secret" move, but no surprise to the towns people of Washington Court House, Ohio, who had waited four days for the division to arrive. There were movies, food, hot water for shaving and a mammoth banner saying "Welcome First Armored Division" across the main street. At Dix there were 36 hour passes to New York and motor parks jammed with division vehicles. Nobody knew when or where the division was going.

The trip was to Northern Ireland, and the division landed in May and June. Training for the next few months was even more rigid and exacting than during the last months in the United States. The men were mentally and physically at their best. The general feeling was one of impatience.

At the end of the training period Combat Command "B", with about one-half of the division's troops, was alerted to leave Ireland and prepare for an overseas trip where "…. You'll get off fighting."

Alerted for the invasion were the 1st Battalion of the 1st Armored Regiment, the 1st and 2nd Battalions of the 13th Armored Regiment, nearly all the 6th Armored Infantry Regiment, the 27th Armored Field Artillery Battalion, "B" and "C" Companies of the 701st Tank Destroyer Battalion, and detachments of the 16th Armored Engineer Battalion, the Supply Battalion, the Maintenance Battalion, 47th Armored Medical Battalion and the 141st Signal Company.

Combat operations

The 1st Armored Division was ordered to Fort Dix on 11 April 1942 to await their deployment overseas. The division's port call required them to board the RMS Queen Mary at the New York Port of Embarkation at the Brooklyn Army Terminal on 11 May 1942. They arrived at Northern Ireland on 16 May 1942, and trained on the moors until they moved on to England on 29 October 1942.

The unit's first contact with an enemy was as part of the Allied invasion of Northwest Africa, Operation Torch, on 8 November 1942. Elements of the division were part of the Northern Task Force and became the first American armored division to see combat in World War II. Combat Command B (CCB) of the division landed east and west of Oran under the command of Brigadier General Lunsford E. Oliver, and entered the city on 10 November 1942. On 24 November 1942, CCB moved from Tafaroui, Algeria to Bedja, Tunisia, and raided Djedeida airfield the next day. Djedeida was finally conquered on 28 November 1942. CCB moved southwest of Tebourba on 1 December 1942, engaged German forces on El Guessa Heights on 3 December 1942, but its lines were pierced on 6 December 1942. CCB withdrew to Bedja with heavy equipment losses between 10 and 11 December 1942, and was placed in reserve. CCB next attacked in the Ousseltia Valley on 21 January 1943, and cleared that area until 29 January 1943 when sent to Bou Chebka, and arrived at Maktar on 14 February 1943.

Combat Command A (CCA) fought at Faid Pass commencing on 30 January 1943, and advanced to Sidi Bou Zid, where it was pushed back with heavy tank losses on 14 February 1943, and had elements isolated on Djebel Lessouda, Djebel Kasaira, and Garet Hadid. Combat Command C (CCC), which had been constituted on 23 January 1943 to raid Sened Station on 24 January, advanced towards Sbeita, and counterattacked to support CCA in the Sidi Bou Zid area on 15 February 1943, but was repulsed with heavy losses. The division withdrew from Sbeita on 16 February 1943, but – by 21 February 1943 CCB contained the German attack toward Tebessa. The German withdrawal allowed the division to recover Kasserine Pass on 26 February 1943 and assemble in reserve. The division moved northeast of Gafsa on 13 March 1943 and attacked in heavy rains on 17 March 1943 as CCA took Zannouch, but became immobilized by rain the next day. The division drove on Maknassy on 20 March 1943, and fought the Battle of Djebel Naemia on 22–25 March 1943, and then fought to break through positions barring the road to Gabès between 29 March and 1 April 1943. It began to follow up the withdrawing German forces on 6 April 1943, and attacked towards Mateur with CCA on 27 April 1943, which fell after hard fighting on Hill 315 and Hill 299 on 3 May 1943. The division fought the Battle for Djebel Achtel between 5 and 11 May 1943, and entered Ferryville on 7 May 1943. The German forces in Tunisia surrendered between 9 and 13 May 1943. The division was reorganized in French Morocco, and began arriving in Naples, Italy on 28 October 1943.

After the Allied invasion of Sicily, the unit, part of the U.S. Fifth Army, invaded mainland Italy. It took part in the attack on the Winter Line in November 1943. It then flanked the Axis armies in the landings at Anzio, and then passed through the city of Rome and pursued the retreating enemy northward until mid-July 1944. At that point, Major General Harmon was replaced by Major General Prichard, who led the 1st AD through the rest of the war. Three days after Major General Prichard took command, the division was reorganized, based on experiences in the North Africa Campaign. The change was drastic. It eliminated the armored and infantry regiments in favor of three separate tank and infantry battalions, disbanded the Supply Battalion, and cut the strength of the division from 14,000 to 10,000. The result of the re-organization was a more flexible and balanced division, with roughly equivalent infantry and tank battalions. These forces could be combined or custom-tailored by the command to meet any situation. The additional infantry strength would prove particularly useful in the future campaigns in the largely mountainous combat of the Italian campaign. The division continued in combat to the Po Valley until the German forces in Italy surrendered on 2 May 1945. In June, the division moved to Germany as part of the occupation forces.

Casualties

- Total battle casualties: 7,096[22]

- Killed in action: 1,194[22]

- Wounded in action: 5,168[22]

- Missing in action: 216[22]

- Prisoner of war: 518[22]

During the war, the Old Ironsides division captured 41 towns and cities and 108,740 prisoners. 722 division soldiers were awarded the Silver Star, 908 received the Bronze Star. The division received 5,478 Purple Hearts. Two division soldiers were awarded the Medal of Honor during World War II, Private Nicholas Minue and Second Lieutenant Thomas Weldon Fowler.

The 1st Armored Division flag returned to the New York Port of Embarkation on 24 April 1946, and was inactivated at Camp Kilmer, New Jersey on 25 April 1946. The component headquarters and units stayed in Germany were retasked and renamed as a component of the United States Constabulary.

After World War II

1950s

The success of the Russian made T-34 tank at the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950 brought renewed enthusiasm for armor. As part of the Korean War buildup of American forces, the 1st Armored Division was reactivated at Fort Hood, Texas on March 7, 1951.

Old Ironsides became one of the first divisions in the Army to integrate black soldiers throughout the ranks. It was also the only combat-ready armored division in the continental United States and the first to receive the M48 Patton Tank. Training for nuclear war became a major theme in the mid-1950s. Accordingly, the 1st Armored Division participated in tests of the "Atomic Field Army" at Fort Hood and in Operation Sagebrush, the largest joint maneuver conducted since World War II. Upon completion of the exercise in February 1956, the 1st Armored Division moved to its new home at Fork Polk, Louisiana.[23]

Cuba

At the end of the 1950s, the Army’s focus on a nuclear battlefield waned. The Army experienced years of austere budgets. Reduced in size and moved back to Fort Hood, the 1st Armored Division reverted to a training cadre for new inductees. The start of the 1960s, however, inaugurated a period of military renewal. Important changes in organization, doctrine, and equipment occurred.[23]

In 1962, the 1st Armored Division was brought back to full strength and reorganized. Brigades replaced combat commands, and the division’s aviation assets doubled. Intense training followed the reorganization. In October 1962 the 1st Armored Division was declared combat ready, just before the Cuban Missile Crisis. In response to the Soviet stationing of missiles in Cuba, the division deployed from Fort Hood, Texas to Fort Stewart. The entire operation took just 18 days.[23]

For the next six weeks, the 1st Armored Division conducted live-fire training and amphibious exercises on the Georgia and Florida coasts. One highlight was visit from President John F. Kennedy on November 26, 1962. Shortly thereafter, tensions eased and the 1st Armored Division returned to Ft. Hood.

Vietnam

Although the 1st Armored Division did not participate as a division in the Vietnam War, two units, Company A, 501st Aviation and 1st Squadron, 1st Cavalry served in Vietnam. Both earned Presidential Unit Citations, and 1-1 Cavalry received two Valorous Unit Awards and three Vietnamese Crosses of Gallantry. Neither unit was officially detached from the 1st Armored Division thus veterans of both units may wear the division's patch as a combat patch. In addition, in 1967 the 198th Infantry Brigade was formed from three of the division’s infantry battalions and deployed from Fort Hood to Vietnam. After the war, two of the three battalions, 1-6 Infantry and 1-52 Infantry, returned to the 1st Armored Division.

In 1968, rioting broke out in many American cities following the assassination of Martin Luther King. The 3rd Brigade deployed to Chicago to assist in restoring order.

The early 1970s brought the withdrawal of American forces from Vietnam and a major restructuring of the Army. Old Ironsides was rumored to be on the list of units to be inactivated. Veterans of the division organized a letter-writing campaign to "save" the 1st Armored Division.

As part of the Army's post-Vietnam reorganisation, the 1st Armored Division was moved to West Germany in 1971. It replaced the 4th Armored Division in the Bavarian city of Ansbach. The Division headquarters remained in Ansbach, with brigade units in the neighboring towns of Bamberg, Illesheim, Fürth (Nuremberg), Schwabach, Katterbach, Crailsheim, Erlangen and Zirndorf for the next twenty years, as part of VII Corps, itself part of NATO's Central Army Group.

1st Battalion, 51st Infantry (Mech), at Crailsheim, part of the 1st Brigade, was inactivated on June 16, 1984. This was a result of the division's conversion to the Division 86 force structure. Under the Division 86 structure, each heavy division decreased by one infantry battalion, while remaining infantry battalions gained one additional rifle company.

On 16 April 1986, the Aviation Brigade, 1st Armored Division, was activated in Germany.

Gulf War

In August 1990, Iraq invaded Kuwait. On Nov. 8, 1990, the 1st Armored Division received orders to deploy to Southwest Asia to provide an offensive option, should Saddam refuse to withdraw from Kuwait. This provided an abrupt change of focus for the division, from a U.S. forces "build down" in Europe to a sudden "buildup" in Southwest Asia.

Division leaders and soldiers began focusing on planning, training and unit deployment. Planning offered two challenges. First, the division had to be shipped to Saudi Arabia in a logical order to support the buildup for combat operations. European heavy divisions had never practiced this monumental task.

Commanders and their staffs rapidly integrated new equipment into their units for deployment to the Persian Gulf region. The division also prepared to receive new units: 3rd Brigade, 3rd Infantry Division replaced 1st Brigade, 1st Armored Division. Round-out units such as the 312th Support Center (RAOC) composed of reservists from throughout Germany, also joined the division. Other units, such as the 54th and 19th Engineer battalions, the 218th Military Police Company, and the 7th Support Group, joined 1st AD in Kuwait.

The All units concentrated on individual and unit training, including gunnery, in the few weeks available prior to personnel deployment, concurrently preparing vehicles for overseas movement. The division qualified 355 tanks and 300 Bradley crews on Tables VII and VIII, conducted division artillery howitzer section gunnery, fired modified Vulcan Table VIII and qualified Stinger and Chaparral crews. Battle drill rehearsals and wargaming seminars were also part of the rigorous training agenda.

The division transported equipment by rail, wheeled convoy, and rotary wing self -deployment. These movements unavoidably occurred on short notice or in bad weather, with challenges of coordination and logistics. Units labored long days, including weekends, to deploy. The first trains departed for port the last week of November 1990, a movement that continued into the second week of December 1990

Movement to TAA Thompson

The division convoyed on Tactical Assembly Area (TAA) Thompson, southeast of Hafar Al Batin in Saudi Arabia, between December 14 and January 24, 1991, from the Persian Gulf. One of the great dangers Iron Soldiers faced during "Operation Desert Shield" and "Desert Storm" was that of traffic accidents during the convoy to TAA Thompson, as they convoyed from the Port of Entry. The Tapline (Trans Arabian Pipeline) Road was a paved but bumpy road, wide enough for two and a half vehicles but regarded by Saudi truck drivers as a four-lane super highway. Convoys from the intermediate staging area to Thompson took 15–20 hours and entailed numerous hazards and obstacles: traffic jams, long refueling stops, driver fatigue and reckless Saudi truck drivers. Fortunately, "Old Ironsides" sustained no fatalities on "Suicide Alley" during the move to TAA Thompson.

Prior to the air campaign, the division's main challenges in the TAA were security, life support - particularly hygiene, the buildup of the division's combat power, contingency planning and mental preparation for combat. Preparation for an Iraqi pre-emptive strike in conjunction with terrorist attacks increased security measures during the division's concentration. All units maintained a high security profile to include daily stand-to, around-the-clock security, and constant improvement of fighting positions.

Life support issues also were a high priority. Key concerns were proper waste disposal, personal cleanliness, creature comforts, mail, and the use of telephones. Wooden showers and latrines raised morale, while burning human waste became a daily ritual. The highlight of each day was mail call, while the 120-phone AT&T "fest tent" allowed soldiers an occasional phone call home.

Another challenge during the buildup in Thompson was preparation for an Iraqi pre-emptive attack. Despite his numerous heavy divisions, Saddam continued to tie his units to fixed defenses. The threat of an Iraqi attack spurred the 1st AD buildup of combat power in Thompson. Logisticians vied with corps for more HETs for tank, BFV and artillery transport. Ammunition was another critical issue as Hellfire missiles, artillery Copperhead rounds, M1A1 SABOT rounds, Stingers, TOWs and .50 caliber rounds required intense management. The failure of the Baker-Aziz talks on Jan. 9 showed that the Iraqis were not ready to withdraw. Offensive operations were imminent.

Air campaign

In the early hours of Jan. 17, Coalition air and naval forces struck devastating blows against the Iraqi Air Force, air defense, command, control, communications and intelligence systems. Coalition air strikes quickly gained air supremacy. The air campaign focused on strategic targets, such as Iraq's nuclear, biological and chemical capabilities, and operational targets, primarily Iraq's Republican Guard heavy divisions. The air attacks continued for 39 days.

Much training occurred in the four weeks prior to movement to Forward Assembly Area (FAA) Garcia. The division maneuvered under a "crawl, walk, run" concept that progressed from leader walk-throughs to unit rehearsals at squad to brigade level. Training peaked with brigade maneuver of combat, combat support and combat service support elements over long distances. Firing at Eskey Range, by maneuver and fire support units, occurred regularly. Units focused on offensive tactics, including movement techniques, attack formations, actions on contact and breaching obstacles in stride. Combat service support units worked two missions simultaneously. They provided needed life support for the brigades and separate battalions and focused on desert fundamentals to support mobile armored warfare.

The VII Corps mission was to breach defensive positions in Iraq and set the stage for 1st AD's envelopment of the RGFC west of the breaching site. The plan's success depended on a successful air campaign, effective intelligence and a theater level deception plan. Prior to ground combat, the Coalition succeeded in attriting Iraqi tanks and fighting vehicles by at least 23 percent and artillery by 47 percent. Iraqi units in the KTO continued to take a tremendous beating. Front line infantry divisions were the worst equipped and least supported, and they suffered most from allied air. While Iraqi mechanized and armor divisions serving as operational and strategic reserves also suffered from Coalition air, they were in much better shape and prepared to conduct combat operations.

Intermediate staging area (ISA)

For most 1st AD soldiers the deployment to Saudi Arabia entailed an eight-hour plane flight, interrupted by a maintenance halt in Rome. After arrival at either Dhahran or King Fahd Airfield, soldiers rode 100 kilometers in a bus to the intermediate staging areas (ISA) near the ports of Al Jubayl or Ad Dammam. The division occupied two ISAs: ISA North at Al Jabayl, and ISA South at Ad Dammam. Conditions at the ISA North weres dusty, crowded (10,000 or more soldiers crammed 16-20 persons in each tent), and often unsanitary. Contracted food ranged from acceptable to poor, and caused some illness. Conditions at the ISA South were somewhat better. Both camps contained some amenities: a WolfBurger stand, Baskin Robbins, a PX, MARS phones and occasional mail. Some units spent Christmas at the ISA by contracting for their own food and preparing it themselves. The emphasis on individual training continued, as leaders held classes on desert survival skills. In many ways, the ISA prepared soldiers for desert life, because it exposed them to dust, moisture, sanitation and maintenance problems.

While soldiers trained and maintained equipment, division and brigade staff officers continued planning. Planners devised an operational concept, which they wargamed and refined. The All Source Intelligence Center (ASIC) received, processed and disseminated intelligence products, templates and maps. Maps remained a key issue- 1st AD needed 1: 10,000 maps, but ARCENT opted for 1:50,000 maps as the theater standard.

Move to FAA Garcia

After completing pre-combat training, inspections and preparations in TAA Thompson, home for the last six weeks, the division began a 150-kilometer westward move to FAA Garcia. The division was working under the planning assumption that G-Day (the anticipated start of the allied ground offensive) would be on or about Feb. 21. Shifting the division west was expected to accomplish three things: reposition the division to its eventual attack sector, contribute to the theaterwide deception plan designed to fix Iraqi forces in Kuwait, and to rehearse division, brigade and battalion battle formations as well as command and control procedures over a distance similar to the plan of attack.

On Feb. 14, the move started with 1st Squadron, 1st Cavalry crossing Main Supply Route (MSR) Sultan, the road from Hafr Al Batin to Riyadh at 5:36 a.m. Using well-marked routes set up by the 16th Engineer Battalion and guided by military policemen from the 501st and 218th Military Police companies, the cav squadron led the 1st, 3rd and 4th Brigades, Force Artillery and DISCOM over the northern crossing sites, while 2nd Brigade, the Division Main Command Post (DMAIN) and elements of 141st Signal Battalion crossed further south.

After completely closing into Staging Area (SA) Mac, just north of King Khalid Military City (KKMC), the division prepared for the rehearsal phase of the move. 1st AD moved out early on February 16 behind the 2nd Armored Cavalry Regiment and south of 3rd Armored Division with all battalions practicing movement to contact battle drills and movement techniques. The move to FAA Garcia took two days with the division making another crossing of an MSR (the Tapline Road west of Hafr Al Batin) and closing into the FAA on February 18.

With the final G-Day determination not yet made, allied attack helicopter feints and artillery raids kept the Iraqis guessing about operations over the next several days. Iron Soldiers used time available in FAA Garcia to continue pre-combat preparations, conduct rehearsals, and rest. The division's combat support soldiers from the DISCOM and forward support battalions continued to build up supplies and equipment in Log Base Echo, about 25 km east of the division's main body in Garcia. G-3 (Feb. 21)

Though the division's main combat effort did not occur for another four days, the division's first actual combat operation was conducted as part of a theater-wide deception effort. In the days before the actual ground offensive, deep artillery fires and attack helicopter raids were executed to fix Iraqi forces in the vicinity of the Wadi Al Batin. On the night of February 20, 4th Battalion, 27th Field Artillery and Battery A, 94th Field Artillery, equipped with a Multiple Launch Rocket System (MLRS), moved 50 kilometers east from FAA Garcia s to the 1st Cavalry Division's sector near the Kuwait-Iraq-Saudi Arabia tri-border area. The next day, the two artillery units joined with elements of the 1st Cavalry Divisions's division artillery to attack known and suspected enemy locations in Iraq at noon and 3 p.m. During the first mission 26 of 27 self-propelled launchers (SPL) fired 312 rockets and 23 of the SPLs fired 276 more rockets on the second mission. The units then returned to division control in FAA Garcia and continued to prepare for future combat operations. G-1 (Feb. 23)

As part of the final preparation for the operation, the division's leaders conducted a two-hour sand model exercise at the division tactical command post (DTAC) at 1 p.m. All commanders and key staff officers down to battalion task force and separate company level rehearsed the opening phases of the division's operational plan. While the rehearsal was underway elements of the 19th Engineer Battalion moved earth-moving equipment to within six kilometers of the Saudi Arabia-Iraq international border berm. Sixteen bulldozers poised to breach the berm, the first anticipated obstacle to the division's northward movement. After the rehearsal confirmation of enemy positions throughout the sector of operations to the vicinity of Al Busayyah was finalized using aerial photos. The Force Artillery and direct support artillery battalions (2nd and 3rd Battalions, 1st Field Artillery and 2nd Battalion, 41st Field Artillery) adjusted target areas and brigade S2s were updated. At 9:15 p.m., an AH-64 Apache attack helicopter company from 3rd Battalion, 1st Aviation Regiment of the division's 4th Brigade, conducted armed reconnaissance missions out to Phase Line (PL) MELON. The results of the recon supported the division G2's prediction of few enemy forces capable of impeding the initial attack.

War begins, February 24, 1991 G-Day

At approximately 6:30 a.m. 19th Engineers began berm breaching operations. By mid-afternoon more than 250 eight-meter-wide lanes were constructed along the division's 18 km front. Earlier in the day the VII Corps Headquarters received word of unexpected success of offensive operations already underway in the XVIII Airborne Corps sector (to the far west) and US Marines' (MARCENT) sector (near the coast) of the allied front. The corps instructed 1st Armored Division to be prepared to launch its attack at noon, 18 hours ahead of schedule. At noon, the corps placed the division on a two-hour alert to initiate the attack. When ordered, the division crossed its assigned line of departure (LD) at 2:34 p.m. when lead elements of 1-1 Cavalry crossed the border berm.

In spite of limited visibility caused by an intense sand and dust storm, 1st AD moved rapidly northward in a narrow front in a compressed "division wedge" formation. 3rd Armored Division accompanied the division on its eastern flank as the main effort of the corps' deep envelopment of Iraqi defenses west of the Wadi Al Batin. 1st Brigade (TF 1-7 Infantry, TF 4-7 Infantry, TF 4-66 Armor, 26th Support Battalion and 2-41 Field Artillery) the division advance guard, followed 10 km behind the 1-1 Cav screen. 2nd Brigade (TF 6-6 Infantry, TF 1-35 Armor, TF 2-70 Armor TF 4-70 Armor, 47th Support Battalion and 2-1 Field Artillery) followed on the left (west) of sector and 3rd Brigade (TF 7-6 Infantry, TF 1-37 Armor, TF 3-35 Armor, 125th Support Battalion and 3-1 Field Artillery) followed on the right (east) as Maj. Gen. Ronald Griffith, division commander, centered the Force Artillery behind the 1st Brigade and between the wing brigades. The division's support elements (including 123rd Support Battalion), totaling nearly 1000 vehicles, brought up the rear of the division's battle formation.

The division moved forward with 2nd Brigade encountering difficult terrain in the west which combined with the poor weather conditions to briefly slow its movement. Foreword of the division, 1-1 Cav reported the division's first battle casualties-three soldiers wounded by fragments from unexploded ordnance. At 3 p.m. the corps shifted the fire support coordination line (FSCL) out to PL Pear to ease control of artillery fires and U.S. Air Force close air support. Soon after that the division encountered its first enemy prisoners of war (EPW), the processing of which also slowed the attack somewhat. At 4 p.m. the division air force liaison officer (ALO) reported that deteriorating weather conditions precluded the use of close air support for the rest of the day though selected air engagement areas remained open in case the weather improved. The division's advance reached the area just north of PL Apple, 30 km past the LD, at 6:05 p.m. Nearing dark the division was ordered to halt its attack so that it could realign flank units (3rd Armored Division and 3rd Armored Cavalry Regiment in the west). 1st AD units used the pause to refuel and prepare to continue the attack.

With elements of Iraqi 26th Division believed to be in the vicinity PL Colorado (northwest of Al Thamarya) the CG decided to continue the attack the following morning at 6:30. At 10:22 p.m. intelligence reports indicated that the Iraqi III Corps commander had ordered his units in Kuwait to begin a withdrawal, the first indication that Iraqi defenses were cracking.

G + 1 Feb. 25, 1991

All units were refueled by 2:06 a.m. and there was no significant enemy contact during the remainder of the night. The division continued the attack at 6:30 a.m. with 1st Brigade crossing PL Louisiana and making initial contact with elements of the 26th Iraqi Infantry Division as expected. The brigade's easternmost battalion task force, TF 4-7 Infantry, handed off the battle to the 3rd Brigade as the remainder of the Phantom Brigade shifted west to bypass the pocket and continue the attack north ahead of the 2nd Brigade. At 7:37 a.m. the coordinated fire line (CFL) shifted to PL Grape. 3rd Brigade quickly destroyed one T-62 tank, eight armored personnel carriers (APC), and three artillery pieces.

The division crossed PL Melon at 8:15 a.m. when the 1st Brigade, led by the 1-1 Cav, made contact with elements of the 26th Division between PL Colorado and PL Arizona. After 2-41 FA placed indirect fires on the Iraqis, TF 1-7 Infantry used psyops loudspeaker teams to flush out a large group of prisoners. 1-1 Cav continued moving, reporting its crossing of PL Kansas at 8:38. To ease fire control coordination, corps shifted the CFL twice during the next hour to PL Arkansas (8:42) then PL Arizona (9:30). At 10:32 a.m. 3rd AD reported its lead units were crossing PL Melon. After the CFL was again shifted to PL Pear, Force Artillery initiated an MLRS fire mission against an enemy multiple rocket launcher (MRL) in the 3rd AD sector. At 1:22 p.m. the 2nd Brigade crossed PL Arkansas. After destroying eight APCs, four artillery pieces, several trucks and capturing 272 EPWs, the 1st Brigade reported its objective secured at 2:48. At 3:08 p.m. the CFL was shifted once more to PL New Mexico and the FSCL to PL Orange.

While the ground action was occurring, the 4th Brigade conducted afternoon AH-64 deep attacks against Al Busayyah (Attack Position Python and Objective Collins), the anticipated site of the division's next fight. The weather deteriorated rapidly with heavy thunderstorms developing by late afternoon. Because Al Busayyah was believed to be the site of the 26th Division headquarters and was a known logistics center, the division commander decided to conduct a deliberate attack the following morning at 6:30, preceded by an intense artillery preparation. At dark 1st Brigade held PL North Carolina in the east, 2nd Brigade held PL North Carolina, in the west, 3rd Brigade consolidated along PL South Carolina, and 1-1 Cav extended its screen north from PL Smash to PL New Mexico. With further reports coming in from corps indicating that Iraqi resistance was crumbling rapidly in the XVIII Airborne Corps and MARCENT sectors, the division took advantage of this second tactical pause to finalize plans to push through Al Busayyah and exploit its early success. The commanding general decided to execute a rapid turning movement to the east to continue the attack to destroy elements of the elite Republican Guards forces. In its first day of significant enemy contact the division destroyed two tanks (T-62 and T-55), 25 APCs, nine artillery pieces, 48 trucks, 14 air defense artillery (ADA) systems, and captured 314 prisoners.

G + 2 Feb. 26, 1991

Throughout the night continuous artillery fire was placed on Al Busayyah culminating in a massive combined 155mm and MLRS barrage at 6:15 a.m. The prep was followed immediately by a coordinated attack which had 1st Brigade attacking in the south, 2nd Brigade in the north and 3rd Brigade following 1st Brigade, prepared to exploit success by passing the Phantom Brigade to the southeast and continuing the attack in zone. 1-1 Cav again extended its screen line out to PL Texas to facilitate future operations.

1st and 2nd Brigades had significant contact with 26th Division elements in and around Al Busayyah but overcome it rapidly and continued the attack to the north and east out to PL Texas with 2nd Brigade in the north and 1st Brigade in the south. 3rd Brigade trailed the 1st as the division reserve.[24]

2nd Brigade left a mechanized infantry battalion task force (TF 6-6 Infantry) and Company A, 16th Engineer Battalion to mop up the Al Busayyah area, discovering large stockpiles of fuel, water and ammunition in the process. TF 6-6 rubbled the town and log sites with 155mm artillery fires and 165mm main gun fire from a combat engineer vehicle (CEV), commanded by engineer Sgt. Darryl Breedlove of the 16th. Five enemy tanks, numerous wheeled command and control and support vehicles, bunkers and arms caches were destroyed. In anticipation of future operations the G2 updated the division with a new enemy template for the Iraqi Madinah Republican Guards Armored Division situated well to the east near Objective Bonn.

The division completed most of the action around Al Busayyah by noon when the 75th Artillery Brigade (MLRS, Army Tactical Missile System (ATACMS), 8", and 155mm) reinforced the Force Artillery. At 4:24 p.m. USAF A-10s sighted 17 enemy tanks in the vicinity of PL Tangerine, the planned LD for the next phase of the operation-the attack to destroy the Republican Guards. The A-10s destroyed three tanks and more close air support (CAS) attacked while the division moved forward. By 6 p.m., when the division crossed PL Tangerine, it had completed a sweeping turning movement, reorienting its attack a full 90 degrees in less than six hours. The division shifted its attack formation to three brigades abreast-2nd in the north, 1st in the center and 3rd in the south-to maximize its firepower and shock effect against the Republican Guards.

Upon crossing PL Tangerine air scouts reported elements of the Tawakalna Republican Guards Armored Division and the 52nd Mechanized Infantry Division to the east. 1-1 Cav made contact with the two divisions in the vicinity of PL Poland where the unit's scouts identified 52 tanks. Air scouts and AH-1 Cobra attack helicopters stayed on station while air strikes and artillery fires from the Force Artillery destroyed 30 of the enemy's tanks. 3rd Brigade attacked in the south to destroy 22 more tanks and numerous other armored and wheeled support vehicles. The night attack continued with lead brigades reporting their arrival at PL Libya at 10: 10.

Again, as with the engagement at Al Busayyah, AH-64s from 4th Brigade and CAS attacked deeper targets in vicinity of Objective Bonn, confirmed to be the site of the Madinah Division as well as the site of numerous logistics facilities. In the northern portion of the division sector near PL Spain, the Force Artillery conducted MLRS raids on positions of the ADNAN Republican Guards Infantry Division. The strikes effectively eliminated resistance from the ADNAN while pilot reports indicated heavy enemy presence at OBJ BONN. By midnight February 26, the division had destroyed 112 more tanks, 82 APCs, two artillery pieces, 94 trucks, two ADA systems and captured another 545 EPWs.[24]

G + 3 Feb. 27, 1991

Night fighting continued into the early hours with the most significant contact in the 3rd Brigade sector against the northern brigade of the TAWAKALNA. Across the division boundary 3rd Armored Division engaged the southern brigade of the TAWAKALNA. During the heat of the fighting in this sector four M1A1 tanks of the 3rd Brigade were hit by direct fire. All four crews survived the incident with only a few light injuries. At 3:10 a.m. 1-1 Cav's command post received incoming artillery fire, again with no fatalities and remarkably light injuries to 22 soldiers, only three of which were litter urgent. In an unrelated action the first division fatality of the battle also occurred during the night when an engineer soldier from Company C, 54th Engineer Battalion was killed at Umm Hajul Airfield near Al Busayyah.[24]

At 4:40 a.m. 1-1 Cav destroyed seven BMPs west of PL Spain. Later, at 6:18 VII Corps reported that the Madinah and Hamurabi Republican Guards Divisions were still in place further east. Because of the rapid pace of operations over the preceding 36 hours, by first light all brigades had serious fuel shortages, especially in tanks and helicopters. The division spent much of February 27 marshalling all available fuel assets including an emergency push of fuel from corps and 3rd Armored Division. A major contributor to the effort was Spec. Krist R. Johnson, a crew chief from 2-1 Aviation Battalion, who braved a suspected enemy minefield and area littered with unexploded munitions to lead a convoy of fuel trucks to the Apaches.[24]

The attack again halted in the vicinity of PL Spain as 2nd Brigade received incoming artillery fire from north of the division boundary. Force Artillery nominated two Iraqi FROG missile battalions and one cannon artillery battalion as ATACMS targets. XVIII Airborne Corps cleared elements of the 3ACR from the proposed target area and VII Corps cleared 1AD (6th Battalion, 27th Field Artillery) for target destruction. By 8:10 a.m. 1st and 2nd Brigades began destroying elements of the Madinah Division along PL Lime with 3rd Brigade joining the fight at about 8:35. At 9:50 counterfire radars of the Force Artillery acquired enemy artillery emplacements firing on the 2nd Brigade. During several intense counterbattery engagements A Battery, 94th FA (MLRS) quickly reduced the effects of the enemy fire, permitting the 2nd Brigade attack to continue. When enemy prisoners began surrendering in mass across the division's sector at 10:00 a.m. the 4th Brigade sent AH-64s on an armed reconnaissance mission destroying a number of withdrawing armored vehicles in the vicinity of PL Monaco.

By midday the 2nd Brigade was fully engaged with the Madinah's 2nd Brigade and, in the largest single engagement of the war, destroyed 61 Iraqi T-72/T-55 tanks, 34 APCs and five SA13 air defense systems in less than one hour. The division spent the rest of the day destroying the madinah's equipment in detail and paused east of PL Italy. At 5 p.m. the corps passed information to the division that a theater-wide cease-fire was imminent. The division was urgently instructed to continue the attack as soon as possible with a limit of advance designated as PL Brazil and a limit of fire at PL Kiwi. Because there were still significant elements of the Madinah Division in OBJ Bonn, General Griffith intended to continue the attack early on February. 28, stating that he wanted the accompanying artillery preparation "to be the most awesome artillery prep known to man."

In its heaviest day of fighting the division's battle damage assessment for Feb. 27 was 186 enemy tanks, 127 APCs, 38 artillery pieces, five air defense systems, 118 trucks destroyed and 839 prisoners captured. The division lost one soldier, a scout from 4th Battalion, 66th Armor, killed in action during the day's fighting.[24]

G + 4 Feb. 28, 1991

At 5:30 a.m. the Force Artillery's 45 minute preparatory barrage began with 155mm, 8", and MLRS strikes that lasted until 6:15. It was immediately followed by a series of AH-64 strikes which were completed shortly before 7 a.m. The ground maneuver brigades attacked abreast and crossed PL Italy at 7:05. The brigades made contact with remnants of the Madinah Division and other Iraqi divisions fleeing northeast toward Al Bashrah. A corps-wide cease-fire was called at approximately 6:45 when a MLRS battery commander located in the 3rd AD sector put out an emergency call when he thought his unit was under friendly fire. About 20 minutes later the corps commander ordered the attack to continue after the situation was sorted out. Though the delay prevented the division from moving further east than PL Monaco when the cease-fire went into effect at 8 a.m., it had accomplished its mission by destroying two brigades of the Madinah.

The division consolidated along PL Italy, a few miles from the Iraq-Kuwait border, and prepared a hasty defense with 2nd Brigade in the north, 1st Brigade in the center, 3rd Brigade and 1-1 Cav lagering to the rear of PL Italy. Wartime rules of engagement remained in effect, but the division's chemical protective MOPP level was downgraded to 0.

In the brief engagements of Feb. 28 the division destroyed 41 more Iraqi tanks, 60 APCs, 15 artillery pieces, 244 trucks, 11 ADA systems and captured 281 additional EPWs. Within hours of the cease-fire unexploded ordnance in the sector claimed the life of a third soldier, an engineer from the 19th Engineers.[24]

Summary

During 89 hours of sustained offensive combat and mopping up operations in the first several days after the cease-fire, the 1st Armored Division destroyed 418 enemy tanks, 447 armored personnel carriers, 116 artillery pieces, 1211 trucks and 110 air defense systems. The division drove deeper and faster into the enemy's rear areas than any other division-size force in the Kuwait Theater of Operations. While moving 259 kilometers, the division destroyed the 1st Brigade of the 26th Iraqi Infantry Division, along with two brigades of the elite Madinah Republican Guards Armored Division, one brigade of the elite Tawakalna Republican Guards Mechanized Division, two brigades of the 52nd Armored Division, several battalions of the 17th Armored Division, and elements of 10 other Iraqi Army divisions.

The division responsible for destroying the major base of the 26th Infantry Division, eight other theater level logistics sites and four log bases from the Madinah Division as well as capturing 2234 Iraqi prisoners of war from the Madinah, Tawakalna, Adnan, and Hamurabi Republican Guards Divisions; the 7th, 20th, 25th, 26th, 27th, 28th, 30th, 31st and 48th Iraqi Infantry Divisions; and the 10th, 12th, 17th and 52nd Armored Divisions. The division's own battle losses were light: 1 M1A1 Abrams main battle tank was destroyed and three others damaged and repaired, two M3A2 Bradley cavalry fighting vehicles damaged, one M113A2 armored personnel carrier destroyed, two AH-64 Apache attack helicopters damaged, one HEMMT fuel truck damaged, four high mobility multipurpose wheeled vehicles (HMMWV) destroyed, and one commercial utility cargo vehicle (CUCV) destroyed. The division lost two soldiers killed in action during the fight (Cpl Douglas L. Fielder, Company C, 54th Engineer Battalion and Spec. Clarence A. Cash, HHC, 4-66 Armor), two killed after the fight (SSgt. Steven Hanson, 19th Engineer Battalion, and Spec. Manuel Sapien Jr., HHB, 6-3 ADA), and 52 wounded in action.

1AD returned to Germany on 8 May 1991, and was visited by Vice President Dan Quayle.

Battle damage assessment

- 25 Feb: 2 tanks, 25 APC, 9 artillery, 14 ADA, 48 trucks, 314 EPW

- 26 Feb: 112 tanks, 82 APC, 2 artillery, 2 ADA, 94 trucks, 545 EPW

- 27 Feb: 186 tanks, 127 APC, 66 artillery, 5 ADA, 118 trucks, 839 EPW

- 28 Feb: 41 tanks, 60 APC, 15 artillery, 11 ADA, 244 trucks, 281 EPW

- 01 - 12 Mar: 99 tanks, 191 APC, 98 artillery, 105 ADA, 879 trucks, 4,707 EPW

- Total: 440 tanks, 485 APC, 190 artillery, 137 ADA, 1,383 trucks, 6,686 EPW[25]

Four division soldiers were KIA and 52 WIA during the Gulf War[25]:232

The Balkans

On 18 December 1995, under the command of Major General William L. Nash, the division deployed to northeast Bosnia as the command element of Task Force Eagle, a powerful, multinational unit intended to keep the peace. (A Russian brigade, initially under the command of Colonel Aleksandr Ivanovich Lentsov, was part of that effort. An account of the interactions of the Americans and Russians in Bosnia in 1996 may be found in James Nelson's Bosnia Journal.) The 1AD returned in late 1996 to Germany.

In 1999, the unit once again deployed, this time to Kosovo, for Operation Allied Force, and Operation Joint Guardian. Afterwards, the unit trained heavily in Hohenfels and Grafenwöhr Training Areas in Germany, with realistic OPFOR (Opposition Forces) exercises.

The 1st Armored Division began the year 2000 as the 1st Brigade Combat Team trained at Grafenwoehr Training Area (GTA). February 2000 saw 1st Armored Division Headquarters announce the closure of military facilities in Bad Kreuznach and subsequent relocation to Wiesbaden scheduled for June 2001. The 1st Armored Division trained at HTA and GTA in three separate exercises in March 2001. Ready First participated in Mountain Guardian III at Hohenfels, a mission rehearsal exercise for Kosovo.

The 1st Armored Division's command and control elements conducted a warfighter exercise in GTA between March 21 and April 17, 2001. The 1st Armored Division took command of Task Force Falcon in Kosovo as Brigadier General Randal Tieszen accepted the colors from 1st Infantry Division's Brigadier General Ricardo Sanchez. The 1st Armored Division celebrated its 60th birthday at home and abroad in Kosovo, on 15 July 2001. Major General George W. Casey, Jr. traveled to Boston Harbor in August 2001 where he connected with Commander Bill Foster of the USS Constitution.

Iraq

In the build-up in the months prior the March 2003 invasion of Iraq, two battalions of the 1st Armored Division's 3d Brigade were deployed in support of Operation Iraqi Freedom. The 2–70 Armor and 1–41 Infantry battalion task forces augmented the 82nd Airborne Division , the 3d Infantry Division, and the 101st Airborne Division throughout the campaign to oust Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein. These units spearheaded the U.S assaults in As Samawah and Karbala and later occupied the southern area of Baghdad. The 1–13 Armor battalion followed shortly behind towards the end of March 2003.

In May 2003, the division deployed to Iraq and assumed responsibility for Baghdad, under command of Major General Ricardo Sanchez, relieving the 3d Infantry Division. The division was scheduled to return to Germany in November 2003, but was extended an additional 3 months in order to oppose a Shia militia led by Moqtada Al Sadr. Near the end of that period the division was extended an additional three months before it could be relieved. During the first three-month extensions Task Force 1–37 AR ("Bandits") fought Al Sadr's forces in Karbala while Task Force 2–37 AR ("Dukes") along with elements of 2–3 FA (Gunners) fought in Diwaniya, Sadr City, Al-Kut, and Najaf. Task Force 1–36 IN ("Spartans") became the CJTF-7 Operational Reserve and conducted operations throughout the theater in support of the 1st Cavalry Division. Forces from the 2d Brigade fought in Kut. During its 15-month deployment, the division lost 133 soldiers.

3rd Brigade deployments

In early 2003, approximately 1,300 soldiers with the 3rd Brigade, 1st Armored Division received orders to deploy to Iraq. Additionally, 400 more reservists received orders to mobilize through Fort Riley to deploy with the brigade. The 3rd Brigade was at the time stationed at Fort Riley, having activated there on 16 February 1996. The brigade was deployed from 20 February 2003 to 15 April 2004.

Under the command of Colonel Russ Gold, the brigade participated in both the ground war and the immediate fight to stop a growing insurgency.In September 2003, the brigade participated in "Operation Bulldog Flytrap," in which the brigade captured insurgents they called the Mad Mortar Men from the Abu Ghraib area. They killed seven insurgents who were responsible for improvised explosive devices and roadside bombs. The mission also was the first to use helicopters to fire in Iraqi cities.

During Operation Bulldog Mammoth, the brigade captured 58 terrorists and foreign fighters and recovered hundreds of weapons from an area near the Abu Ghraib Prison.

In November 2003, the brigade executed Operation Cancer Cure. After a lieutenant from the unit was killed in a firefight, the brigade discovered the Sunni extremist group responsible. The insurgents were using mosques as their meeting places because U.S. troops were not allowed to enter the holy sites. After gathering several sources of intelligence, the brigade was given permission by the local citizenry to enter the mosque after prayer services. On November 10, 2003 the brigade conducted raids in and around Baghdad, and detained 18 men suspected of taking part in the Oct. 26 Al Rasheed Hotel missile attack that killed one Army officer and wounded 16 personnel. The brigade also captured 19 members of the black list, better known as the "deck of cards." The brigade was awarded the Valorous Unit Award for their actions during the deployment.

After only nine months at home station, 3rd Brigade once again deployed to the Iraqi Theatre in Feb 2005 for Operation Iraqi Freedom Three from Fort Riley, Kansas. The brigade spent the deployment attached to the 3d Infantry Division aoperating in Taji, north of Baghdad.

2nd BCT in Kuwait and Iraq: 2005 – 06

2nd Brigade Combat Team, 1st Armored Division, led by Col. Robert Scurlock, Jr. and Command Sgt. Maj. Jose Santos, deployed in early November 2005 from Baumholder, Germany in support of Operation Iraqi Freedom 05-07. The Iron Brigade was the first heavy brigade combat team to serve as the Central Command theater reserve, located in Kuwait, ready to respond anywhere in Iraq. The brigade consisted of seven battalions: 1st Battalion, 6th Infantry; 2nd Battlion, 6th Infantry Regiment; 4th Battlion, 27th Field Artillery Regiment; 1st Battalion, 94th Field Artillery Regiment; 1st Battalion 35th Armored Regiment; 4th Engineer Battalion; and the 47th Forward Support Battalion – in all about 3,500 troops. The brigade trained at Camp Buehring, Kuwait. While there, the soldiers conducted the first Expert Infantryman badge and Expert Field Medical Badge training in a combat environment. To stay proficient on all weapon systems, the Iron Birgade built a fully functional multi-purpose range complex, which allowed units to conduct full mounted and dismounted gunnery qualifications tables, which facilitated both Abrams tanks and Bradley fighting vehicles.

On March 12, 2006, Task Force 2-6 (2nd Battalion, 6th Infantry Regiment) linked up with 4th Infantry Brigade in Baghdad. By May, the remainder of the brigade was in position in Iraq with 2-6 Infantry in southern Baghdad and B Company 2-6 IN (in support of the 1st Marine Expeditionary Force "Air Ground Team"), 1-6 Infantry, 1-35 Armor, 2nd Platoon of the 501st MP Company, and a forward logistics element from the 47th Forward Support Battalion in Ar Ramadi supporting Colonel MacFarland’s 1st Brigade, 1st Armored Division. In Ramadi, those soldiers who participated in the 2003-04 deployment found it to be a very different war. Within the first month of arriving, over 100 IEDs were found, as roadside bombs had become the main tool for the insurgents.

In late July, at the request of the Government of Iraq and Multi-National Division-Baghdad, the brigade headquarters moved to Western Baghdad to begin Operation Together Forward. The Iron Brigade received control of several units, including 1st Battalion, 22nd Infantry Regiment, 4th Infantry Division; 8th Squadron, 10th Cavalry Regiment, 4th Infantry Division; and 1-23 Infantry, 3rd SBCT, 2nd Infantry Division. During Operation Together Forward, the brigade went into areas where violence was much higher than anywhere else in Baghdad. TF 2-6 was assigned the Amariyah, Ghazaliyah, and Shulah areas with a mission to isolate and clear out the violence along with the Iraqi army. TF 2-6 was also assigned the Abu Ghraib area and turned the Abu Ghraib internment facility over to ministry of justice.

A major difference in this deployment was the interaction and cooperation from the local populace. More Iraqi civilians were willing to help and there was a greater presence of local Iraqi police and military operations. The objective was to cut the flow of weapons and insurgents coming in from Ramadi and Fallujah. As a result of the efforts of TF 2-6, hundreds of Iraqi insurgents and foreign fighters were killed or captured, weapons caches seized, criminals and terrorists cleared out and reconstruction efforts underway. The brigade conducted counter-IED operations, route reconnaissance, civil-military operations and counter-mobility operations.

The 2nd Brigade Combat Team returned to Baumholder, Germany in November 2006 having lost 28 soldiers who died in Ramadi and the Al Rashid district of southern Baghdad.

Ready First

The division's 1st Brigade Combat Team ("Ready First") under the command of Colonel Sean B. MacFarland deployed again to Iraq in January 2006 after months of intensive training in Grafenwöhr and Hohenfels, Germany. Many of the soldiers who fought with units like 1–36 Infantry ("Spartans"), 2–37 Armor ("Iron Dukes"), and 1–37 ("Bandits") during the invasion of Iraq returned for a second tour. Most of 1st BCT was initially deployed to Northern Iraq in Nineveh province concentrating on the city of Tal' Afar. In May 2006, the main force of 1st Brigade received orders to move south to the city of Ramadi in volatile Al Anbar Province.[26]

Since 2003, Al Anbar served as a base of operations for the Sunni insurgency and al Qaeda. Ramadi, its capital, had neither a government nor a police force when the brigade arrived. Most military strategists inside and outside of the Bush administration believed that the war in Anbar had already concluded unsuccessfully. Al Qaeda in Iraq publicly announced Ramadi as now the capital of their new caliphate, the city alone averaged more than twenty attacks per day, the province was statistically the most dangerous location in the country, and the insurgency enjoyed free rein throughout much of the province.[27]

Ramadi

When 1st BCT arrived in Ramadi in June 2006 with more than 70 M1 Abrams tanks and 84 Bradley fighting vehicles, many locals believed the brigade was preparing for a Fallujah-style block-by-block clearing assault on the city and many insurgents fled the city. Following Colonel H.R. McMaster’s "Clear, Hold, Build" strategy, the brigade developed a plan to isolate the insurgents, deny them sanctuary, and build Iraqi security forces.

1-1 moved into some of Ramadi's dangerous neighborhoods and, beginning in July 2006, built four of what would eventually become eighteen combat outposts. The soldiers brought the territory under control and inflicted many casualties on the insurgents. On 24 July, AQI launched a counterattack, initiating 24 assaults, each with about 100 fighters, on American positions. Despite the reported presence of AQI leader Abu Ayyub al-Masri, the insurgents failed in all of their attacks and lost about 30 men.[28]

Independence Day

Simultaneous with combat operations, the brigade was working on the "hold" portion of clear, hold, build. Lieutenant Colonel Tony Deane, commander of Task Force 1-35 Armor, approached Sheik Abdul Sattar Bezia al-Rishawi of the Abu Risha tribe in an attempt to recruit his tribesmen to the police force. This move worked against the US administration in Iraq’s plan to develop representative government and modernity throughout Iraq, a plan that would remove power from sheiks.

Jim Michaels, in his book "A Chance in Hell" about the operation in Al Anbar wrote that the US had a flawed view on civil government, one that ignored the tribal history of Iraq. "The tribal system embraced elements of democracy. The sheik may not be elected," wrote Michaels," but nor is he born into his job. Sheiks are generally selected by a group of elders….Throughout history, ignoring the tribes [in Iraq] has never been a smart move. Sheiks have wielded power for thousands of years and survived countless efforts to blunt their influence in the name of modernity."[26]:89

To facilitate Sheik Sittar, Colonel MacFarland's deputy, Lieutenant Colonel Jim Lechner, and his police implementation officer, Marine Major Teddy Gates, changed the location for Iraqi Police recruiting. They wanted a more secure location close to Sattar's house, as this would enable them to build a police station north of the Euphrates River in an area where many potential recruits lived. Having already had his father and three brothers killed by AQI, Sattar appreciated the idea. Residents responded was overwhelming by standing in line to serve as IP’s at the next recruiting drive.

In August, the new Jazeera police station north of the river, manned mostly by Abu Ali Jassim tribe members, was attacked and the sheikh of the tribe killed. AQI then hid the sheikh's body so it was not found for several days, a violation of Islam's strict burial rules that call for interment within 24 hours.

The attack on the station killed several Iraqi police and also caused a number of burn casualties. Colonel MacFarland offered the police evacuation to Camp Blue Diamond, an American Army camp outside of Ramadi, while they repaired the station. But the Iraqis refused to abandon their post and instead put their flag back up and resumed patrolling that same day.[29]

Awakening

With the locals outraged by AQI's disregard of Islamic funeral laws, the charismatic Sattar stepped forward to continue the push toward working with the Americans.[30] On 9 September 2006, he organized a tribal council, attended by more than 50 sheiks as well as Col. MacFarland, at which he declared an "Anbar Awakening" officially underway, with an Awakening Council dedicated to driving AQI out of Ramadi, then establish rule of law and local governance. The Anbar Awakening was suddenly a real movement and Sittar its leader. McFarland, speaking later about the meeting, said, "I told them that I now knew what it was like to be in Independence Hall on 4 July 1776 when the Declaration of Independence was signed." While attacks remained high through October 2006, the Awakening, and with it, Sittar’s influence, began to spread. AQI, realizing it was losing its grip on the human terrain, launched a counterattack on the Sufia tribal area on November 25. The attack, intended to terrorize and insult the Sufia tribe, as 1st BCT’s M1A1 tanks reinforced tribal defenders, further reinforcing a growing bond.

By early 2007, Al Anbar was a rare success in the war. The combination of tribal engagement and combat outposts was defeating AQI’s in Ramadi and throughout the province. President Bush, in his January 23, 2007 State of the Union speech referred to Al Anbar as a place "where al Qaeda terrorists have gathered and local forces have begun showing a willingness to fight them."[31]

"The Gettysburg of this war"

By February 2007, contacts with insurgents dropped almost 70 percent since June 2006, and they decreased in complexity and effect. By the summer of 2007, the fighting in Al Anbar was mostly over. Frederick Kagan, resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, called Al Anbar "the Gettysburg of this war, to the extent that counterinsurgencies can have such turning points," writing "Progress in Anbar and throughout the Sunni community has depended heavily on a skillful balance between military force and political efforts at the local level."[32]

The tactics, techniques, and procedures used by 1st BCT were groundbreaking at the time, but came to serve as the philosophical basis for the surge in Iraq.[33] In nine months, 85 soldiers, sailors, and Marines were killed, and over 500 wounded.

Division Headquarters redeploys

In September 2007, in the midst of a national debate about troop levels in Iraq and, more broadly, about the US strategy in Iraq, the 1st Armored Division Headquarters deployed again to Iraq. General Petraeus’ surge strategy was in effect, with major counterinsurgency operations across the country. "This is a pivotal and historic time for the 1st AD, for the forces in Iraq and for the nation," said Brig. Gen. James C. Boozer, a deputy commanding general for 1st AD at the time of the division’s deployment.[34] The division began its deployment the same day Petraeus delivered his Report to Congress on the Situation in Iraq, concluding that "the military objectives of the surge are, in large measure, being met."

The division, commanded by then-Major General Mark Hertling, conducted a relief in place with the 25th Infantry Division and assumed command of Multi-National Division North, headquartered in Tikrit, Iraq, on 28 October 2007, just as Colonel MacFarland’s Anbar Awakening was pushing AQI out of Anbar. At the time in northern Iraq, enemy attacks averaged 1,800 a month, the Iraqis had little trust in their central government, and the unemployment rate was high.

General Hertling assumed responsibility of all Coalition forces in Northern Iraq. Multi-National Division North was composed of five maneuver brigade combat teams, a combat aviation brigade, a fires brigade, and an engineer brigade. The division had responsibility includes the Iraqi provinces of Ninawa, Kirkuk (formerly at Tamin), Salah ad Din, and Diyala along with Dahuk, and As Sulaymaniah. The area included the critical cities of Tal Afar, Mosul, Bayji, Tikrit, Kirkuk, Samarra, Balad, Baqubah, Dahuk, and Sulaymaniah. Arbil province remained aligned as a separate Multi-National Division, North-East. The division area of operations included ethnic fault lines between Arabs and Kurds, religious fault lines between Sunni and Shia Muslims, numerous tribal regions, and the complexities involving significant former regime elements. 1AD immediately applied a mix of lethal and non-lethal counterinsurgency tactics, as maneuver battalions partnered with State Department officials and provincial reconstruction teams. Commanders applied a focused lethality, protecting the Iraqi population while killing insurgents in large volumes.[35]

Rather than viewing every Iraqi as a potential enemy, the division followed Colonel MacFarland’s approach, building relationships and getting cooperation from the Iraqis against Al Qaeda and minimizing the number of enemies for U.S. forces. Soldiers were asked to use measures of restraint, often putting themselves at risk to avoid killing civilians or damaging property.

The strategy worked and over a 15-month tour northern Iraq improved. The Iraqi government developed slowly, but had systems of economy, infrastructure development, and security in place. The Iraqi people gained confidence in their security forces. The progress in the region came at the cost of 104 U.S. soldiers assigned to the division killed and 891 wounded. The division transferred responsibility to Headquarters 25th Infantry Division on 8 December 2008 and returned to Wiesbaden Army Airfield in Germany.[36]

2nd BCT in Mada'in Qada, 2008-09

In April 2008 the 2nd BCT out of Baumholder, Germany deployed to the Mada'in Qada region of Southeast Baghdad. The brigade, commanded by Colonel Pat White, replaced the Third Brigade of the Third Infantry Division, commanded by Colonel Wayne Grigsby who, four years later, would serve as the Deputy Commanding General for Operations for the 1st Armored Division. The "Iron Brigade" conducted 14 months of combat operations, partnering with the 2nd Battalion, 25th Iraqi Army Brigade. The brigade built on the work of Colonel Grigsby's 3/3 ID, which cleared Salman Pak, an insurgent safe haven in 2006. Throughout their deployment, 2nd BCT helped the local leaders of the Mada'in Qada communities and the Iraqi Security Forces to rebuild and rejuvenate the area. While 3/1 ID quelled the AQI forces operating in the area, 2/1 built capacity in the local government and security forces. 2nd BCT returned to Germany in May 2009. On 30 Jul 2009 it cased its colors and reflagged as the 170th BCT, initiating the brigade's move to Fort Bliss, Texas.

4/1 AD as first advise and assist brigade