A Vindication of Natural Diet

A Vindication of Natural Diet is an 1813 essay by Percy Bysshe Shelley on vegetarianism and animal rights. It was first written as part of the notes to Queen Mab, which was privately printed in 1813. Later in the same year the essay was separately published as a pamphlet.

Background

Shelley wrote four essays on the subject of vegetarianism, "A Vindication of Natural Diet" (1813), the note in Queen Mab, in a section of "A Refutation of Deism" (1814), and "On the Vegetable System of Diet", which was published posthumously in 1929.[1][2][3] Shelley first experimented with a vegetarian diet while at Oxford University according to Thomas Jefferson Hogg.[4] Shelley began a vegetarian diet on 1 March 1812 along with his first wife Harriet Westbrook. Shelley began composing the essay in October–November 1812.

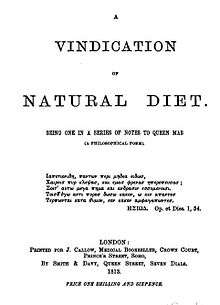

The essay was reprinted in 1884 in a new edition in London by F. Pitman and by John Heywood and the Vegetarian Society in Manchester. The original title page was reproduced: A Vindication of Natural Diet. Being One in a Series of Notes to Queen Mab (A Philosophical Poem). London: Printed for J. Callow by Smith & Davy, 1813. The new edition featured a preface by Henry Stephens Salt and William Axon.

Vegetarianism

Shelley wrote in "A Vindication of Natural Diet", in heartfelt dedication to sentient beings:[5] "If the use of animal food be, in consequence, subversive to the peace of human society, how unwarrantable is the injustice and the barbarity which is exercised toward these miserable victims. They are called into existence by human artifice that they may drag out a short and miserable existence of slavery and disease, that their bodies may be mutilated, their social feelings outraged. It were much better that a sentient being should never have existed, than that it should have existed only to endure unmitigated misery"; "Never again may blood of bird or beast/ Stain with its venomous stream a human feast,/ To the pure skies in accusation steaming"; and "It is only by softening and disguising dead flesh by culinary preparation that it is rendered susceptible of mastication or digestion, and that the sight of its bloody juices and raw horror does not excite intolerable loathing and disgust."[5]

Shelley used the imagery of slaughtering a lamb. In Queen Mab: A Philosophical Poem (1813) he wrote about the change to a vegetarian diet using the lamb imagery: "And man ... no longer now/ He slays the lamb that looks him in the face,/ And horribly devours his mangled flesh."[6]

In the novel Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus (1818), which Shelley co-wrote,[7][8] the Being is portrayed as a vegetarian. The lamb imagery is retained. The Being explained his vegetarian diet to Victor Frankenstein: "My food is not that of man. I do not destroy the lamb and the kid to glut my appetite; acorns and berries afford me sufficient nourishment.”

Shelley argued that eating meat was unnatural. He maintained that diseases and immorality arose from mankind's "unnatural habits of life". A meatless diet was the best regimen for maintaining a healthy and disease-free lifestyle. He wrote that human diseases could be decreased by a return to a natural vegetable diet.[9] Shelley argued that eating meat was a practice that polluted the body with syphilis and resulted in other ailments. In A Vindication of Natural Diet he wrote, "Should ever a physician be born with the genius of Locke, I am persuaded that he might trace all bodily and mental derangements to our unnatural habits,"[10] these unnatural habits being the consumption of meat. He cited the allegory of Prometheus who stole fire from the gods which enabled mankind to cook meat, thereby screening the disgust and horror of dead flesh. Shelley also compared a meat diet to alcoholism, inquiring, "How many thousands have become murderers and robbers, bigots and domestic tyrants, dissolute and abandoned adventurers, from the use of fermented liquors?"[10] Shelley used comparative anatomy to show that the human digestive system resembles that of frugivorous or plant-eating animals. He concluded that a person with compassion and empathy for animals, "rising from a meal of roots," would be able to maintain a healthy and balanced diet and lifestyle. Shelley presented examples of how a vegetarian diet resulted in longevity and an increased lifespan. The only threat of death will be that of natural, old age.[5] The two rules he prescribes for a natural diet are to never eat anything that was alive and to drink only distilled water.

References

- ↑ Spencer, Colin. The Heretic's Feast: A History of Vegetarianism. Great Britain: Hartnolls Ltd, Bodmin. 1993, pp 244–45.

- ↑ Morton, Timothy, "Joseph Ritson, Percy Shelley and the Making of Romantic Vegetarianism." Romanticism, Vol. 12, Issue 1, 2006, pp. 52–61.

- ↑ Clark, David Lee. "The Date and Source of Shelley's 'A Vindication of Natural Diet'." Studies in Philology, Vol. 36, No. 1, January 1939.

- ↑ Hogg, Thomas Jefferson. The Life of Percy Bysshe Shelley. London, 1858, I, p. 238.

- 1 2 3 Shelley, Percy Bysshe, "A Vindication of Natural Diet;" London: Smith & Davy. 1813, pp. 1–36.

- ↑ Preece, Rod. Sins of the Flesh: A History of Ethical Vegetarian Thought. Vancouver, BC, Canada: University of British Columbia Press, 2008.

- ↑ Adams, Stephen. "Percy Bysshe Shelley helped wife Mary write Frankenstein, claims professor: Mary Shelley received extensive help in writing Frankenstein from her husband, Percy Bysshe Shelley, a leading academic has claimed", The Telegraph, 24 August 2008.

- ↑ Grande, James. Review: The Original Frankenstein, By Mary Shelley with Percy Shelley ed Charles E Robinson. "To what extent did Percy Bysshe Shelley work on 'Frankenstein'? A new analysis reveals all", The Independent, 16 November 2008.

- ↑ Spencer, Colin, The Heretic's Feast: A History of Vegetarianism; Great Britain: Hartnolls Ltd, Bodmin. 1993, pp. 244–45.

- 1 2 Shelley, Percy Bysshe, "A Vindication of Natural Diet;" London: Smith & Davy. 1813, pp. 16.

Sources

- Spencer, Colin. The Heretic's Feast: A History of Vegetarianism. Great Britain: Hartnolls Ltd, Bodmin. 1993, pp 244–45.

- Morton, Timothy, "Joseph Ritson, Percy Shelley and the Making of Romantic Vegetarianism." Romanticism, Vol. 12, Issue 1, 2006. pp. 52–61.

- Morton, Timothy. Shelley and the Revolution in Taste: The Body and the Natural World. Cambridge University Press, 1994.

- Shelley, Percy Bysshe, "A Vindication of Natural Diet;" London: Smith & Davy. 1813, pp. 1–36.

- Preece, Rod. Sins of the Flesh: A History of Ethical Vegetarian Thought. Vancouver, BC, Canada: University of British Columbia Press, 2008.

- Chapin, Lisbeth. "Science and Spirit: Shelley's Vegetarian Essays and the Body as Utopian State." A Brighter Morn: The Shelley Circle's Utopian Project. Edited by Darby Lewes. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2003.

External links

- Online version.

- Audio recording by Amy Gramour on LibriVox.

- Online version of 1884 reprint on Gutenberg.org.

- 1884 reprint edition.

- Shelley's Vegetarianism by William E. A. Axon, 1891.

- Animal Rights: A History. Percy Bysshe Shelley.