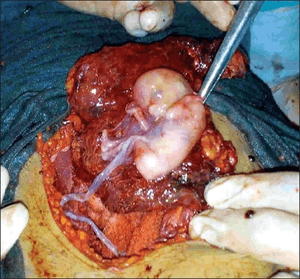

Abdominal pregnancy

| Abdominal pregnancy | |

|---|---|

|

Abdominal pregnancy being delivered | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | obstetrics |

| ICD-10 | O00.0O83.3 |

| ICD-9-CM | 633.00 |

| eMedicine | 557082_5 |

An abdominal pregnancy can be regarded as a form of an ectopic pregnancy where the embryo or fetus is growing and developing outside the womb in the abdomen, but not in the Fallopian tube, ovary or broad ligament.[1][2][3]

While rare, abdominal pregnancies have a higher chance of maternal mortality, perinatal mortality and morbidity compared to normal and ectopic pregnancies but, on occasion a healthy viable infant can be delivered.[4]

Because tubal, ovarian and broad ligament pregnancies are as difficult to diagnose and treat as abdominal pregnancies, their exclusion from the most common definition of abdominal pregnancy has been debated.[5]

Others - in the minority - are of the view that abdominal pregnancy should be defined by a placenta implanted into the peritoneum.[6]

Symptoms and signs

Symptoms may include abdominal pain or vaginal bleeding during pregnancy.[1] As this is nonspecific in areas where ultrasound is not available the diagnosis was often only discovered during surgery to investigate the abnormal symptoms.[1] They are typically diagnosed later in the developing world than the developed.[7] In about half of cases from a center in the developing world the diagnosis was initially missed.[8]

It is a dangerous condition as there can be bleeding into the abdomen that results in low blood pressure and can be fatal. Other causes of death in people with an abdominal pregnancy include anemia, pulmonary embolus, coagulopathy, and infection.[9]

Risk factors

Risk factors are similar to tubal pregnancy with sexually transmitted disease playing a major role;[9] however about half of those with ectopic pregnancy have no known risk factors - known risk factors include damage to the Fallopian tubes from previous surgery or from previous ectopic pregnancy and tobacco smoking.[10]

Mechanism

Implantation sites can be anywhere in the abdomen but can include the peritoneum outside of the uterus, the rectouterine pouch (culdesac of Douglas), omentum, bowel and its mesentery, mesosalpinx, and the peritoneum of the pelvic wall and the abdominal wall.[11][12] The growing placenta may be attached to several organs including tube and ovary. Rare other sites have been the liver and spleen,[13] giving rise to a hepatic pregnancy[14] or splenic pregnancy, respectively.[15] Even an early diaphragmatic pregnancy has been described in a patient where an embryo began growing on the underside of the diaphragm.[16]

Primary versus secondary implantation

A primary abdominal pregnancy refers to a pregnancy that first implanted directly in the peritoneum, save for the tubes and ovaries; such pregnancies are very rare, only 24 cases had been reported by 2007.[17] Typically an abdominal pregnancy is a secondary implantation which means that it originated from a tubal (less common an ovarian) pregnancy and re-implanted.[12] Other mechanisms for secondary abdominal pregnancy include uterine rupture, rupture of a uterine rudimentary horn and fimbrial abortion.[4]

Diagnosis

A person with an abdominal pregnancy may feel there is "something not right" or just display the normal signs of pregnancy or have non-specific symptoms such as abdominal pain, vaginal bleeding, and/or gastrointestinal symptoms.[12]

Suspicion of an abdominal pregnancy is raised when the baby's parts can be easily felt, or the lie is abnormal, the cervix is displaced, or there is failed induction of labor.[1] X-rays can be used to aid diagnosis.[12] Sonography can demonstrate that the pregnancy is outside an empty uterus, there is reduced to no amniotic fluid between the placenta and the fetus, no uterine wall surrounding the fetus, fetal parts are close to the abdominal wall, the fetus has an abnormal lie, the placenta looks abnormal and there is free fluid in the abdomen.[9][18] MRI has also been used with success to diagnose abdominal pregnancy and plan for surgery.[17][19] Elevated alpha-fetoprotein levels are another clue of the presence of an abdominal pregnancy.[20] Keyhole (laparoscopic surgery) can also be used to diagnose abdominal pregnancy[21]

Ultrasound

Most cases can be diagnosed by ultrasound.[22] The diagnosis however may be missed with ultrasound depending on the operator's skill.[8][23]

Criteria

To diagnose the rare primary abdominal pregnancy, Studdiford's criteria need to be fulfilled: tubes and ovaries should be normal, there is no abnormal connection (fistula) between the uterus and the abdominal cavity, and the pregnancy is related solely to the peritoneal surface without signs that there was a tubal pregnancy first.[24][25] Studdiford's criteria were refined in 1968 by Friedrich and Rankin to include microscopic findings.[26]

Differential diagnosis

Depending on gestational age the differential diagnoses for abdominal pregnancy include miscarriage, intrauterine fetal death, placental abruption, an acute abdomen with an intrauterine pregnancy and a fibroid uterus with an intrauterine pregnancy .[7]

Treatment

Ideally the management of abdominal pregnancy should be done by a team that has medical personnel from multiple specialties.[27] Potential treatments consist of surgery with termination of the pregnancy (removal of the fetus) via laparoscopy or laparotomy, use of methotrexate, embolization, and combinations of these. Sapuri and Klufio indicate that conservative treatment is also possible if the following criteria are met: 1. there are no major congenital malformations; 2. the fetus is alive; 3. there is continuous hospitalization in a well-equipped and well-staffed maternity unit which has immediate blood transfusion facilities; 4. there is careful monitoring of maternal and fetal well being; and 5. placental implantation is in the lower abdomen away from the liver and spleen.[28] The choice is largely dictated by the clinical situation. Generally, treatment is indicated when the diagnosis is made; however, the situation of the advanced abdominal pregnancy is more complicated.

Advanced abdominal pregnancy

Advanced abdominal pregnancy refers to situations where the pregnancy continues past 20 weeks of gestation (versus early abdominal pregnancy < 20 weeks).[2][29] In those situations, live births have been reported in academic journals[4] and also in the lay press where the babies are not uncommonly referred to as 'Miracle babies'.[30][31] A patient may carry a dead fetus but will not go into labor. Over time, the fetus calcifies and becomes a lithopedion.[32]

It is generally recommended to perform a laparotomy when the diagnosis of an abdominal pregnancy is made.[12] However, if the baby is alive and medical support systems are in place, careful watching could be considered to bring the baby to viability.[12] Women with an abdominal pregnancy will not go into labor. Delivery in a case of an advanced abdominal pregnancy will have to be via laparotomy. The survival of the baby is reduced and high perinatal mortality rates between 40-95% have been reported.[33]

Babies of abdominal pregnancies are prone to birth defects due to compression in the absence of the uterine wall and the often reduced amount of amniotic fluid surrounding the unborn baby.[34] The rate of malformations and deformations is estimated to be about 21%; typical deformations are facial and cranial asymmetries and joint abnormalities and the most common malformations are limb defects and central nervous malformations.[34]

Once the baby has been delivered placental management becomes an issue. In normal deliveries the contraction of uterus provides a powerful mechanism to control blood loss, however, in an abdominal pregnancy the placenta is located over tissue that cannot contract and attempts of its removal may lead to life-threatening blood loss. Thus blood transfusion is frequent in the management of patients with this kind of pregnancy, with others even using tranexamic acid and recombinant factor VIIa, which both minimize blood loss.[1][35]

Generally, unless the placenta can be easily tied off or removed, it may be preferable to leave it in place and allow for a natural regression.[9][12] This process may take several months and can be monitored by clinical examination, checking human chorionic gonadotropin levels and by ultrasound scanning (in particular using doppler ultrasonography.[23] Use of methotrexate to accelerate placental regression is controversial as the large amount of necrotic tissue is a potential site for infection,[9] mifepristone has also be used to promote placental regression.[36] Placental vessels have also been blocked by angiographic embolization.[37] Complications of leaving the placenta can include residual bleeding, infection, bowel obstruction, pre-eclampsia (which may all necessitate further surgery)[22][36] and failure to breast feed due to placental hormones.[38]

Outcome with abdominal pregnancy can be good for the baby and mother, Lampe described an abdominal pregnancy baby and her mother who were well more than 22 years after surgery.[39]

Epidemiology

About 1.4% of ectopic pregnancies are abdominal, or about 1 out of every 8,000 pregnancies.[22] A report from Nigeria places the frequency in that country at 34 per 100,000 deliveries and a report from Zimbabwe, 11 per 100,000 deliveries.[8][29] The maternal mortality rate is estimated to be about 5 per 1,000 cases, about seven times the rate for ectopics in general, and about 90 times the rate for a "normal" delivery (1987 US data).[11]

History

Albucasis (936–1013), the Arab Muslim physician is credited with first recognizing abdominal pregnancy which was apparently unknown to Greek and Roman physicians and was not mentioned in the writings of Hippocrates; Jacopo Berengario da Carpi (1460–1530) the Italian physician is credited with the first detailed anatomical description of abdominal pregnancy. [40]

Natural experiment

Because pregnancy is outside the uterus, abdominal pregnancy serves as a model of human male pregnancy or for females who lack a uterus, although such pregnancy would be dangerous.[41] [42] Abdominal pregnancy has served to further clarify the disease pre-eclampsia which was previously thought (1980's) to require a uterus for it to occur, however pre-eclampsia's occurrence in abdominal pregnancy (with the conceptus outside the uterus) helped throw light on pre-eclampsia's etiology.[43] The ratio of live males to females at birth (normal, 107 males to 100 females[44]) is apparently reduced with abdominal pregnancy to as low as 60 males to 100 females (as reported by Masukume) because males are more likely to die in harsh environments (for example in abdominal pregnancy) compared to females.[4] Cases of combined simultaneous abdominal and intrauterine pregnancy have been reported.[36][45]

External links

- Discovery Health Pregnancy Baby Outside Womb on YouTube

- The 46 Year Pregnancy - Extraordinary People Documentary on YouTube

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Nkusu Nunyalulendho D, Einterz EM (2008). "Advanced abdominal pregnancy: case report and review of 163 cases reported since 1946". Rural Remote Health. 8 (4): 1087. PMID 19053177.

- 1 2 Agarwal, N.; Odejinmi, F. (2014). "Early abdominal ectopic pregnancy: Challenges, update and review of current management". The Obstetrician & Gynaecologist. 16 (3): 193. doi:10.1111/tog.12109.

- ↑ Masukume, Gwinyai (2014). "Insights into abdominal pregnancy". WikiJournal of Medicine. 1 (2). doi:10.15347/wjm/2014.012.

- 1 2 3 4 Masukume G (2014). "Live births resulting from advanced abdominal extrauterine pregnancy, a review of cases reported from 2008 to 2013". WebmedCentral OBSTETRICS AND GYNAECOLOGY. 5 (1): WMC004510.

- ↑ Worley, K. C.; Hnat, M. D.; Cunningham, F. G. (2008). "Advanced extrauterine pregnancy: Diagnostic and therapeutic challenges". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 198 (3): 297.2e1. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2007.09.044.

- ↑ Mahajan, N. N. (2008). "Advanced extrauterine pregnancy: Diagnostic and therapeutic challenges". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 199 (6): e11. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2008.06.024.

- 1 2 Oneko, Olola; Petru, Edgar; Masenga, Gileard; Ulrich, Daniela; Obure, Joseph; Zeck, Willibald (June 2010). "Management of the placenta in advanced abdominal pregnancies at an East african tertiary referral center". Journal of Women's Health. Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. 19 (7): 1369–1375. doi:10.1089/jwh.2009.1704. PMID 20509789.

- 1 2 3 Sunday-Adeoye I, Twomey D, Egwuatu EV, Okonta PI (2011). "A 30-year review of advanced abdominal pregnancy at the Mater Misericordiae Hospital, Afikpo, southeastern Nigeria (1976-2006)". Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 283 (1): 19–24. doi:10.1007/s00404-009-1260-4. PMID 19876640.

- 1 2 3 4 5 KY Kun; PY Wong; MW Ho; CM Tai; TK Ng (2000). "Abdominal pregnancy presenting as a missed abortion at 16 weeks' gestation" (PDF). Hong Kong Medical Journal. 6 (4): 425–7. PMID 11177167. Retrieved January 25, 2009.

- ↑ Barnhart, Kurt T. (23 July 2009). "Ectopic Pregnancy". New England Journal of Medicine. 361 (4): 379–387. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp0810384.

- 1 2 Atrash HK, Friede A, Hogue CJ (1987). "Abdominal pregnancy in the United States: frequency and maternal mortality". Obstet Gynecol. 69 (3 Pt 1): 333–7. PMID 3822281.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Maurice King; Peter C. Bewes; James Cairns; Jim Thornton (eds.). "Primary Surgery; Volume One: Non-trauma. Chapter 8, Abdominal pregnancy". Bonn University. Retrieved 2010-01-25.

- ↑ Anderson PM, Opfer EK, Busch JM, Magann EF (2009). "An Early Abdominal Wall Ectopic Pregnancy Successfully Treated with Ultrasound Guided Intralesional Methotrexate: A Case Report". Obstetrics and Gynecology International. doi:10.1155/2009/247452Case+Report.

- ↑ Chui AK, Lo KW, Choi PC, Sung MC, Lau JW (April 2001). "Primary hepatic pregnancy". ANZ Journal of Surgery. 71 (4): 260–1. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1622.2001.02085.x. PMID 11355741.

- ↑ Yagil Y, Beck-Razi N, Amit A, Kerner H, Gaitini D (2007). "Splenic Pregnancy: The Role of Abdominal Imaging". Journal of Ultrasound Medicine. 26 (11): 1629–32. PMID 17957059.

- ↑ Norenberg DD, Gundersen JH, Janis JF, Gundersen AL (May 1977). "Early pregnancy on the diaphragm with endometriosis". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 49 (5): 620–2. PMID 850582.

- 1 2 Krishna Dahiya; Damyanti Sharma (June 2007). "Advanced Abdominal Pregnancy: A Diagnostic and Management Dilemma". Journal of Gynecologic Surgery. 23 (2): 69–72. doi:10.1089/gyn.2007.B-02259-1.

- ↑ Masukume, G.; Sengurayi, E.; Muchara, A.; Mucheni, E.; Ndebele, W.; Ngwenya, S. (2013). "Full-term abdominal extrauterine pregnancy complicated by post-operative ascites with successful outcome: A case report". Journal of Medical Case Reports. 7: 10. doi:10.1186/1752-1947-7-10. PMC 3544643

. PMID 23302289.

. PMID 23302289. - ↑ Lockhat F, Corr P, Ramphal S, Moodly J (2006). "The value of magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis and management of extra-uterine abdominal pregnancy". Clin Radiol. 61 (3): 264–9. doi:10.1016/j.crad.2005.10.013. PMID 16488208.

- ↑ Tromans PM, Coulson R, Lobb MO, Abdulla U (1984). "Abdominal pregnancy associated with extremely elevated serum alphafetoprotein: case report". British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 91 (3): 296–8. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.1984.tb04773.x. PMID 6200135.

- ↑ Torriente, Martin C.; Steinberg, Wilhelm J. (2015). "Abdominal Pregnancy a Report of Two Cases". International Journal of Medical and Pharmaceutical Case Reports. 2 (4): 101–105. doi:10.9734/IJMPCR/2015/13995. ISSN 2394-109X.

- 1 2 3 Gibbs, Ronald S (2008). Danforth's obstetrics and gynecology (10th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 84. ISBN 9780781769372.

- 1 2 Roberts, R. V.; Dickinson, J. E.; Leung, Y.; Charles, A. K. (2005). "Advanced abdominal pregnancy: Still an occurrence in modern medicine". The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 45 (6): 518. doi:10.1111/j.1479-828X.2005.00489.x.

- ↑ Studdiford WE (1942). "Primary peritoneal pregnancy". Am J Obstet Gynecol. 44: 487–91.

- ↑ Berek, Jonathan S. (2007). Berek & Novak's Gynecology. (14th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 628. ISBN 9780781768054.

- ↑ Friedrich EG Jr; Rankin CA Jr (1968). "Primary pelvic peritoneal pregnancy". Obstet Gynecol. 31 (5): 649–53. PMID 5646396.

- ↑ Renfroe, S.; Dajani, N. K.; Pandey, T.; Magann, E. F. (2013). "Role of serial MRI assessment in the management of an abdominal pregnancy". Case Reports. 2013: bcr2013200495. doi:10.1136/bcr-2013-200495.

- ↑ Sapuri M, Klufio C (March 1997). "A case of advanced viable extrauterine pregnancy" (PDF). Papua New Guinea Medical Journal. 40 (1): 44–47. PMID 10365569.

- 1 2 White RG (March 1989). "Advanced Abdominal Pregnancy – A Review of 23 Cases". Irish Journal of Medical Science. 158 (3): 77–8. doi:10.1007/BF02942151. PMID 2753657.

- ↑ BBC News Health. "Doctors hail 'miracle' baby", BBC News, London, 10 September 1999. Retrieved on 11 November 2014.

- ↑ Jessica Salter. "'Miracle baby' who grew outside the womb", The Daily Telegraph, London, 31 August 2008. Retrieved on 11 November 2014.

- ↑ Medhi, R.; Nath, B.; Mallick, M. (2014). "Lithopedion diagnosed during infertility workup: A case report". SpringerPlus. 3: 151. doi:10.1186/2193-1801-3-151.

- ↑ Martin JN Jr; Sessums JK; Martin RW; Pryor JA; Morrison JC (1988). "Abdominal pregnancy: current concepts of management". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 71 (4): 549–57. PMID 3281075.

- 1 2 Stevens CA (1993). "Malformations and deformations in abdominal pregnancy". American Journal of Medical Genetics. 47 (8): 1189–95. doi:10.1002/ajmg.1320470812. PMID 8291554.

- ↑ Dahab, A. A.; Aburass, R.; Shawkat, W.; Babgi, R.; Essa, O.; Mujallid, R. H. (2011). "Full-term extrauterine abdominal pregnancy: A case report". Journal of Medical Case Reports. 5: 531. doi:10.1186/1752-1947-5-531.

- 1 2 3 Huang K, Song L, Wang L, Gao Z, Meng Y, Lu Y (2014). "Advanced abdominal pregnancy: an increasingly challenging clinical concern for obstetricians". Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 7 (9): 5461–72. PMID 25337188.

- ↑ Cardosi RJ, Nackley AC, Londono J, Hoffman MS (2002). "Embolization for advanced abdominal pregnancy with a retained placenta. A case report". Reproductive Medicine. 47 (10): 861–3. PMID 12418072.

- ↑ Pieh-Holder, K. L.; Scardo, J. A.; Costello, D. H. (2012). "Lactogenesis Failure Following Successful Delivery of Advanced Abdominal Pregnancy". Breastfeeding Medicine. 7 (6): 543. doi:10.1089/bfm.2011.0131.

- ↑ Lampe, L. G. (2008). "Long-term follow-up after abdominal pregnancy". European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 137 (2): 247. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2006.11.023.

- ↑ Cotlar AM (2000). "Extrauterine pregnancy: a historical review(3)". Curr Surg. 57 (5): 484–492. doi:10.1016/s0149-7944(00)00328-7. PMID 11064074.

- ↑ Meryl Rothstein. "Male Pregnancy: A Dangerous Proposition", Popular Science, Bonnier Corporation, 31 July 2005. Retrieved on 12 November 2014.

- ↑ Dick Teresi. "HOW TO GET A MAN PREGNANT", The New York Times, 27 November 1994. Retrieved on 12 November 2014.

- ↑ Moodley J, Subrayen KT, Sankar D, Pitsoe SB (1987). "Advanced extra-uterine pregnancy associated with eclampsia. A report of 2 cases.". S Afr Med J. 71 (7): 460–1. PMID 3563800.

- ↑ Central Intelligence Agency. "WORLD - Sex ratio", The World Factbook, 2014. Retrieved on 12 November 2014.

- ↑ Zacchè, M. M.; Zacchè, G.; Gaetti, L.; Vignali, M.; Busacca, M. (2011). "Combined intrauterine and abdominal pregnancy following ICSI with delivery of two healthy viable fetuses: A case report". European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 154 (2): 232. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2010.10.015.