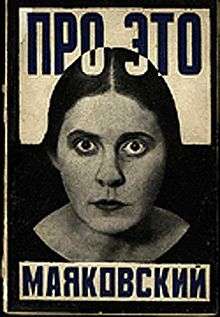

About That

1923 edition, Rodchenko-designed cover | |

| Author | Vladimir Mayakovsky |

|---|---|

| Original title | Про это |

| Country | USSR |

| Language | Russian |

| Genre | Poem |

Publication date | 1923 |

| Media type | Print (Hardback & Paperback) |

About That (Про это) is a poem by Vladimir Mayakovsky written during the self-imposed two-months "exile" after a row with Lilya Brik. It was finished on 11 February 1923 and published on 29 March 1923, originally by the LEF magazine. The poem's first separate edition was illustrated by Alexander Rodchenko who in his montages used photographs made by Mayakovsky and Lilya Brik.[1]

History

In summer 1922 Lilya Brik fell in love with Alexander Krasnoshchyokov, the then head of the newly formed Prombank.[2] Mayakovsky was outraged, a quarrel ensued and the terms of the two-month separation have been agreed between the two. As a result, the poet departed to his 'boat-room' at the Lybyansky Lane, 3/6, "banned" from visiting the Briks at their Vodopyany Lane home. There, working for 16-20 hours a day, he wrote About That. On 11 February it was finished. "That was arguably my best poem in terms of the editorial work done upon it," he later wrote in a preface to the compilation This Year's Things.[3]

There was an entry in Mayakovsky's diary, commenting upon the reasons of his self-imposed exile: "Here I sit alone, but only because I am willing to. Have to think my life over, and myself… Does love mean everything to me? Yes, but in a peculiar sort of way. Love is life, it is the most important of things. That is what verses roll out of, not to speak of other things. Love is the heart of everything. Once it stops beating, everything else dies, becomes superfluous, unnecessary..."[4]

On 28 February 1923 Mayakovsky and Lilya Brik met again and went for several days to Petrograd together. In her 1956 book of memoirs Brik remembered:

I came to the railway station and found him on the platform, waiting for me on the wagon steps. As the train started, Volodya, leaning on the door read me the poem About That. Having finished, he burst into tears, immensely relieved. Now, in the course of those two months I often had pangs of consciousness. Volodya was suffering there alone, while I lived an ordinary life, was seeing people, visiting places. Now I felt happy. For the poem that I've just heard wouldn't have been written should I have not chosen Volodya as my personal ideal and an impersonation of an ideal human being."[5]

On 29 March 1923 the No.3 issue of LEF came out in which the poem was published. On 3 April 1923, speaking at a Proletkult meeting, Mayakovsky made an attempt to define the poem's main idea which, apparently, remained unclear to many of his colleagues. "Here everybody said how impossible it is to capture this poem's leitmotif. What you've heard were only fragments, but even from them the leitmotif is clear: it's the everyday life routines. Which haven't changed, and are still our worst enemy, making the philistines out of us."[3]

After the poem has been finished, the two-month break in Brik-Mayakovsky relations came to an end, but the damage done proved to be irrevocable. "Now I am free from placards and love," Mayakovsky confessed in his poem "For the Jubilee" (1924). Before that Lilya told him she was no longer in love with him, adding: "I think you too love me lesser now and won't be suffering too much." And yet the Briks and Mayakovsky never parted, he continued to support the couple financially and in 1926, when Mayakovsky was granted a state-owned flat at the Gendrikov Lane in Moscow, all three of them moved in and lived there until 1930.[5][2]

Reception

The poem proved to be unpopular with the LEF community. "What a well of sensitivity this 'novel' is… No doubt schoolgirls will soak it with tears. But we in 1923 have no interest for such things whatsoever," wrote the LEF's co-editor Nikolai Chuzhak-Nasimovich.[3]

On the other hand, it made an extraordinary impression upon Anatoly Lunacharsky. In the early March 1923 Mayakovsky for the first time read the poem in public, in the Briks' home, at the Vodopyany Lane. Among those present were Lunacharsky with his wife, actress Natalya Rosenel, Nikolai Aseyev, David Shterenberg, Alexander Rodchenko, Boris Pasternak.

Natalya Lunacharskaya-Rosenel remembered:

Anatoly Vasilyevich has always admired Mayakovsky the performer, but this time Vladimir Vladimirovich was under some particular inspiration. The impression he made was striking, most profound. Anatoly Vasilyevich has been completely captured both by the poem and the rendition… 'I always knew that, but now I've got the proof. Volodya is the subtlest of lyrics even if he does not always understands this himself. The tribune, the agitator, but still the lyric at the same time,' he told me in a car, as we were riding home.[6]

In summer 1923, in Siberia Lunacharsky was still speaking of Mayakovsky's poem with the greatest enthusiasm, praising it as "the huge phenomena." "What struck me was that Anatoly Vasilyevich quoted several fragments of it by heart, without having a written copy, having heard the poem just once… As the poem came out as a separate book, he recited it in full to a group of close friends. Yury Mikhaylovich Yuryev said he "discovered" for him Mayakovsky whom he's 'never understood before'," Lunacharskaya-Rosenel remembered.[5]

References

- ↑ Arutcheva, V.; Paperny, Z. "Commentaries to About That". The Complete V.V.Mayakovsky in 13 volumes. Khudozhestvennaya Literatura. Moscow, 1958. Vol. 4. Retrieved 2015-01-13.

- 1 2 Oboymina, E.; Tatkova, A. "Lilya Brik and Vladimir Mayakovsky". Russian Biographies. Retrieved 2015-01-13.

- 1 2 3 Makarov, V., Zakharov, A., Kosovan, I. Commentaries to About That. The Works by Vladimir Mayakovsky in 6 volumes. Ogonyok Library. Pravda Publishers. Moscow, 1973. Vol.II, pp. 568-569

- ↑ Mikhaylov, Al. (1988). "Mayakovsky". Lives of Distinguished People. Molodaya Gvardiya. Retrieved 2015-01-13.

- 1 2 3 Katanyan, Vasily (1985). "Mayakovsky. The Chronology, 1893-1930 // Маяковский: Хроника жизни и деятельности. Year 1930". Moscow. Sovetsky Pisatel Publishers. Retrieved 1 May 2015.

- ↑ Lunacharskaya-Rosenel, N.A.. The Memory of the Heart // Память сердца. Moscow, 1975. Pp. 24—25.