Sonderaktion 1005

| Sonderaktion 1005 | |

|---|---|

|

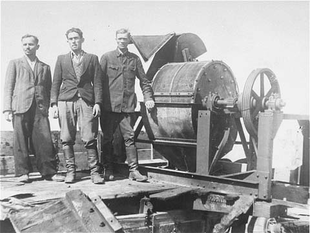

A Sonderkommando 1005 unit stand next to a bone crushing machine at Janowska concentration camp in 1943. | |

| Also known as |

Aktion 1005 or Enterdungsaktion (English: Exhumation action) |

| Location | Nazi-occupied Europe |

| Participants |

|

| Organizations |

SS Police Battalions Sicherheitsdienst Trawnikis |

| Camp |

Extermination camps Concentration camps Mass-killing sites in Eastern Europe. |

| Documentation | Nuremberg trials |

The Sonderaktion 1005 (English: Special Action 1005), also called Aktion 1005, or Enterdungsaktion (English: Exhumation Action) began in May 1942 during World War II to hide any evidence that people had been murdered by Nazi Germany in Aktion Reinhard in occupied Poland. The operation, which was conducted in strict secrecy from 1942–1944, used prisoners to exhume mass graves and burn the bodies. These work groups were officially called Leichenkommandos ("corpse units") and were all part of Sonderkommando 1005; inmates were often put in chains in order to prevent escape.

In May 1943 the operation moved into occupied territories in Eastern Europe to destroy evidence of the Final Solution. Sonderaktion 1005 was used to conceal the evidence of massacres committed by SS-Einsatzgruppen Nazi death squads that had massacred millions of people including 1.3 million Jews according to Historian Raul Hillberg, as well as Roma and local civilians in Eastern Europe. The Aktion was overseen by selected squads from the Sicherheitsdienst and Ordnungspolizei.

Operations

In March 1942, SS-Obergruppenführer Reinhard Heydrich placed SS-Standartenführer Paul Blobel in charge of the Aktion 1005. However its start was delayed after Heydrich was assassinated in June 1942 by Czechoslovakian SOE agents in Operation Anthropoid. It was after the end of June that SS-Gruppenführer Heinrich Müller, head of the Gestapo finally gave Blobel his orders.[1] While the principal aim was to erase evidence of Jewish exterminations, the Aktion would also include non-Jewish victims of Nazi Einsatzgruppen.[1]

Blobel began his work experimenting at Chełmno (Kulmhof). Attempts to use incendiary bombs to destroy exhumed bodies were unsuccessful as the weapons set fire to nearby forests. The most effective way was eventually found to be giant pyres on iron grills. The method involved building alternating layers of corpses and firewood on railway tracks. Afterwards remaining bone fragments could be crushed by pounding with heavy dowels or in a grinding machine and then re-buried in pits.[1] The operation officially began at Sobibór extermination camp. The Leichenkommando exhumed the bodies from mass graves around the camp and then burned them, after which task the workers were executed. The process then moved to Bełżec in November 1942.[2] The Auschwitz and Belsen camps had crematoria with furnace rooms on site to dispose of the bodies, therefore the Aktion 1005 commandos were not needed there.[1] Surplus corpses were burned by their own prisoners (pictured).[3]

The semi-industrial incineration of corpses at the Treblinka extermination camp began as soon as the political danger associated with the earlier burials was realized. In 1943, the 22,000 Polish victims of the Soviet Katyn massacre were discovered near Smolensk in Russia and reported to Adolf Hitler.[4] Their remains were well preserved underground, attesting to the Soviet mass murder. By April 1943, the Nazi propaganda began to draw attention of the international community to this war crime.[4] The Katyn Commission was formed to make detailed examinations in an effort to drive a wedge between the Allies.[5][6] Meanwhile, the secret orders to exhume mass graves and burn the hundreds of thousands of victims instead came directly from the Nazi leadership in April.[7][8] The corpses that had been buried at Treblinka with the use of a crawler excavator were dug up and cremated on the orders of Heinrich Himmler himself, who visited the camp in March 1943. The instructions to utilise rails as grates came from Scharführer Herbert Floss, the camp's cremation expert. The bodies were placed on cremation pyres that were up to 30 metres (98 ft) long, with rails laid across the pits on concrete blocks. They were splashed with petrol over wood, and burned in one massive blaze attended by roughly 300 prisoners who operated the pyres.[1][9] In Bełżec, the round-the-clock operation lasted till March 1943.[2] In Treblinka, it went on at full speed until the end of July.[10]

The operation also returned to the scenes of earlier mass killings such as Babi Yar, Ponary, the Ninth Fort,[1] as well as Bronna Góra.[11] By 1944, with Soviet armies advancing, SS-Obergruppenführer Wilhelm Koppe, head of the Reichsgau Wartheland ordered that each of the five districts of General Government territory set up its own Aktion 1005 commando to begin "cleaning" mass graves. The operations were not entirely successful as the advancing Soviet troops reached some of the sites before they could be cleared.[1]

The aftermath

At the Nuremberg Trials after World War II, a deputy of Adolf Eichmann, SS-Hauptsturmführer Dieter Wisliceny gave the following testimony regarding Aktion 1005.[12]

In November 1942, in Eichmann's office in Berlin, I met Standartenfuehrer Plobel [sic], who was leader of Kommando 1005, which was specially assigned to remove all traces of the final solution of the Jewish problem by Einsatz Groups and all other executions. Kommando 1005 operated from at least autumn 1942 to September 1944 and was all this period subordinated to Eichmann. The mission was constituted after it first became apparent that Germany would not be able to hold all the territory occupied in the East and it was considered necessary to remove all traces of the criminal executions that had been committed. While in Berlin in November 1942, Plobel [sic] gave a lecture before Eichmann's staff of specialists on the Jewish question from the occupied territories. He spoke of the special incinerators he had personally constructed for use in the work of Kommando 1005. It was their particular assignment to open the graves and remove and cremate the bodies of persons who had been previously executed. Kommando 1005 operated in Russia, Poland and through the Baltic area. I again saw Plobel [sic] in Hungary in 1944 and he stated to Eichmann in my presence that the mission of Kommando 1005 had been completed. — SS-Hauptsturmführer Dieter Wisliceny [12]

Blobel was sentenced to death by the U.S. Nuremberg Military Tribunal in the Einsatzgruppen Trial. He was hanged at Landsberg Prison on June 8, 1951. Nearly 60,000 deaths are attributable to Blobel though during testimony at Nuremberg he alleged he only killed between 10,000–15,000 people.[13]

The prosecution at the trial of Adolf Eichmann in 1961 attempted to prove that Eichmann was Blobel's superior, but the court did not accept it. Blobel's superior was in fact Heinrich Müller.[14]

Dramatizations

- Aktion 1005 was depicted in the 1988 TV miniseries War and Remembrance.

- It plays a central role in Daniel Silva's 2005 novel A Death in Vienna.

- Schindler's List also depicts Aktion 1005 when Jewish prisoners were forced to exhume corpses for burning on open pyres.

- Leon Weliczker Wells wrote the book Death Brigade, where he describes his work as part of Sonderaktion 1005, of burning more than 310,000 bodies close to Janowska concentration camp.

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Arad, Yitzhak (1984), "Operation Reinhard: Extermination Camps of Belzec, Sobibor and Treblinka" (PDF), Yad Vashem Studies XVI (Internet Archive), pp. 205–239 (26/30 of current document),

The Attempt to Remove Traces.

- 1 2 Operation Reinhard: "The attempt to remove traces" (reprint) Nizkor.org 2012. Retrieved 5 June 2014.

- ↑ Yisrael Gutman, Michael Berenbaum (1998). Anatomy of the Auschwitz Death Camp. Indiana University Press. pp. 161–163. ISBN 025320884X. Retrieved 30 August 2015.

- 1 2 Davies, Norman (1998), Europe: A History (internal link) (also at Google Books preview), HarperCollins, ISBN 0-06-097468-0

- ↑ International Katyn Commission (30 April 1943). "Commission Findings". Transcript, Smolensk 30 April 1943. Warsaw Uprising by Project InPosterum. Retrieved 5 June 2014.

- ↑ Kużniar-Plota, Małgorzata (30 November 2004). "Decision to commence investigation into Katyn Massacre". Departmental Commission for the Prosecution of Crimes against the Polish Nation. Retrieved 5 June 2014.

- ↑ Sturdy Colls, Caroline (22 January 2012). "Treblinka: Revealing the hidden graves of the Holocaust". BBC News Magazine. Retrieved 5 June 2014.

- ↑ Evans, Richard J. (2008), The Third Reich at War (internal link) (also at Google Books preview), Penguin Books, p. 292, ISBN 978-0-14-311671-4

- ↑ Wiernik, Jankiel (1945), "A year in Treblinka" (Fourteen chapters; digitized by Zchor.org), Verbatim translation from Yiddish, American Representation of the General Jewish Workers' Union of Poland, retrieved 5 June 2014,

The first ever published eye-witness report by an escaped prisoner of the camp.

- ↑ Holocaust Encyclopedia (10 June 2013). "Treblinka". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 5 June 2014.

- ↑ AŻIH, Bronna Góra (Bronnaja Gora). Sites of Martyrdom. Museum of the History of Polish Jews Virtual Shtetl 2014.

- 1 2 Prof. Stuart Stein: "Affidavit of Dieter Wisliceny", from Nazi Conspiracy and Aggression, Volume VIII. USGPO, Washington, 1946, pages 606–619. Note: SS-Hauptsturmführer Dieter Wisliceny in his testimony given before the International Military Tribunal at Nurnberg, 3 January 1946, erroneously identifies the Auschwitz concentration camp complex as the concentration area Sosnowitz (which was one of its dozens of subcamps).

- ↑ Case Closed, Time Magazine, Jun. 18, 1951

- ↑ Ruth Bettina Birn (2011). "Fifty Years After: A Critical Look at the Eichmann Trial". Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law. 44: 443–473.

References

- Arad, Yitzhak, Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka, Indiana University Press, 1992 ISBN 0-253-21305-3

- Edelheit, Abraham J., and Edelheit, Herschel, History of the Holocaust, Westview Press, 1995 ISBN 0-8133-2240-5

- Shmuel Spector, Aktion 1005 — effacing the murder of millions Oxford Journals, Holocaust and Genocide Studies. Volume 5, Issue 2. pp. 157–173.