Alain Prost

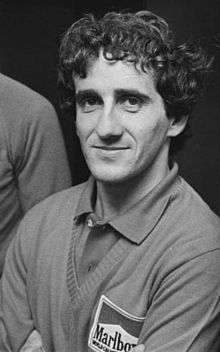

Prost in 2012 | |

| Born |

Alain Marie Pascal Prost 24 February 1955 Lorette, Loire, France |

|---|---|

| Formula One World Championship career | |

| Nationality |

|

| Active years | 1980–1991, 1993 |

| Teams | McLaren, Renault, Ferrari, Williams |

| Entries | 202 (199 starts) |

| Championships | 4 (1985, 1986, 1989, 1993) |

| Wins | 51 |

| Podiums | 106 |

| Career points | 768.5 (798.5)[1] |

| Pole positions | 33 |

| Fastest laps | 41 |

| First entry | 1980 Argentine Grand Prix |

| First win | 1981 French Grand Prix |

| Last win | 1993 German Grand Prix |

| Last entry | 1993 Australian Grand Prix |

Alain Marie Pascal Prost, OBE, Chevalier de la Légion d'honneur (born 24 February 1955) is a French former racing driver. A four-time Formula One Drivers' Champion, only Sebastian Vettel (four championships), Juan Manuel Fangio (five championships), and Michael Schumacher (seven championships) have equalled or surpassed his number of titles. From 1987 until 2001 Prost held the record for most Grand Prix victories. Schumacher surpassed Prost's total of 51 victories at the 2001 Belgian Grand Prix. In 1999, Prost received the World Sports Awards of the Century in the motor sport category.[2][3]

Prost discovered karting at the age of 14 during a family holiday. He progressed through motor sport's junior ranks, winning the French and European Formula Three championships, before joining the McLaren Formula One team in 1980 at the age of 24. He finished in the points on his Formula One début at the San Martin Autodrome in Buenos Aires, Argentina (where he took his first podium a year later) and took his first race victory at his home Grand Prix in France a year later, driving for the factory Renault team.

During the 1980s and early 1990s, Prost formed a fierce rivalry mainly with Ayrton Senna, but also Nelson Piquet and Nigel Mansell. In 1986, at the last race of the season, he beat Mansell and Piquet of Williams to the title after Mansell retired late on in the race, and Piquet was pulled in for a late precautionary pit stop. Senna joined Prost at McLaren in 1988 and the two had a series of controversial clashes, including a collision at the 1989 Japanese Grand Prix that gave Prost his third Drivers' Championship. A year later at the same venue they collided again, but this time Prost, driving for Ferrari, lost out. Before the end of a winless 1991 season Prost was fired by Ferrari for his public criticism of the team. After a sabbatical in 1992, Prost joined the Williams team, prompting reigning drivers' champion Mansell to leave for CART. With a competitive car, Prost won the 1993 championship and retired from Formula One driving at the end of the year.[4]

In 1997, Prost took over the French Ligier team, running it as Prost Grand Prix until it went bankrupt in 2002. From 2003[5] to 2012[6] he competed in the Andros Trophy, which is an ice racing championship, taking 38 race victories and winning the championship 3 times.[7]

Prost employed a smooth, relaxed style behind the wheel, deliberately modeling himself on personal heroes like Jackie Stewart and Jim Clark.[8] He was nicknamed "The Professor" for his intellectual approach to competition. Though it was not a name he particularly cared for, he would admit later that it was an appropriate summation of his approach to his racing. Skilled at setting up his car for race conditions, Prost would often conserve his brakes and tyres early in a race, leaving them fresher for a challenge at the end.[9]

Personal and early life

Alain Prost was born near the town of Saint-Chamond, close to the cities of Lyon and Saint-Etienne in the département of Loire, France, to André Prost and Marie-Rose Karatchian, born in France of Armenian descent.[10] Prost had one younger brother called Daniel, who died of cancer in September 1986.[11] Although short, standing at 1.67 m (5 ft 6 in) Prost was an active, athletic child, who enthusiastically took part in diverse sports, including wrestling, roller skating and football. In doing so he broke his nose several times.[12] He considered careers as a gym instructor or a professional footballer before he discovered kart racing at the age of 14 while on a family holiday.[13] This new sport quickly became his career of choice.

Prost is married to Anne-Marie (born 14 February 1955). They have two sons, Nicolas (born 18 October 1981) and Sacha Prost (born 30 May 1990). Prost also has a daughter, Victoria. As of 2015, Nicolas races in Formula E for e.dams Renault, a team partially run by his father.[14] Prost lived in his hometown, Saint-Chamond, until he and his Renault team fell out in the early 1980s. In April 1983 the Prost family moved to Sainte-Croix, Switzerland, and shortly after to Yens, Switzerland. They moved to Switzerland after Renault workers went to Prost's house in France and burned his Mercedes-Benz.[15] They lived there until November 1999, when they moved to Nyon in the same country.[16] In December 2015, Prost became a grandfather with the birth of Nicolas Prost's son Kimi.

In 1985 Prost was awarded the Légion d'Honneur by President François Mitterrand.[15]

Driving career

Pre-Formula One

Prost won several karting championships in his teens. In 1974 he left school to become a full-time racer, supporting himself by tuning engines and becoming a kart distributor. His prize for winning the 1975 French senior karting championship was a season in French[17] Formula Renault,[18] a category in which he won the title and all but one race in 1976.

Prost went on to win the 1977 Formula Renault European championship before moving up to Formula Three (F3) in 1978. In 1979 he won both the French and European F3 championships, by which time he was on the shopping lists of several Formula One teams.[18] After carefully considering his options, he chose to sign with McLaren for 1980. He surprised the British team by declining their offer of a race drive in a third car at the final race of the 1979 season at Watkins Glen — reasoning that the token effort would benefit neither him nor the team.[19]

Formula One

1980: McLaren

Prost began his career with McLaren (being run by Teddy Mayer) in 1980 alongside Ulsterman John Watson. On his debut in Buenos Aires he finished in sixth place earning one point, something achieved by only a handful of drivers. Prost added four more points to his tally during the season, scoring points at Interlagos, Brands Hatch and Zandvoort. Prost finished the year 15th in the drivers' championship, equalling points with former world champion Emerson Fittipaldi. Despite the encouraging debut season, Prost had several accidents, breaking his wrist during practice at Kyalami and suffering a concussion during practice at Watkins Glen. He also retired from the Canadian round in Montreal a week earlier because of rear suspension failure. At the end of the season, despite having two years remaining on his contract, he left McLaren and signed with Renault. Prost has said that he left because of the large number of breakages on the car and because he felt the team blamed him for some of the accidents.[19]

1981–1983: Renault

- 1981

Prost was partnered with fellow Frenchman René Arnoux for 1981. Motor sports author Nigel Roebuck reports that there were problems between Prost and Arnoux from the start of the season, Prost being immediately quicker than his more experienced teammate.[20] He did not finish the first two Grands Prix, due to collisions with Andrea de Cesaris in Long Beach and Didier Pironi at Jacarepaguá, but scored his first podium finish at Buenos Aires. He also did not finish in the next four races, and then won his first Formula One race at his home Grand Prix in France at the fast Dijon circuit, finishing two seconds ahead of his old teammate John Watson.

For Prost, his debut victory was memorable mostly for the change it made in his mindset. "Before, you thought you could do it," he said. "Now you know you can."[21] Prost led from the start the next 5 races, and won two more races during the season, took his first pole position in Germany and finished on the podium every time he completed a race distance. He won again in Holland and Italy, and finished fifth in the drivers' championship, seven points behind champion Nelson Piquet.

- 1982

Prost won the first two Grands Prix of the 1982 season in South Africa, where Prost recovered from losing a wheel, and Brazil, where he finished 3rd but was awarded the win after Piquet (1st) and Keke Rosberg (2nd) were disqualified. He finished in the points on four other occasions, but did not win again. Despite retiring from seven races, Prost improved on his drivers' championship position, finishing in fourth, but with nine fewer points than the previous year. His relationship with Arnoux deteriorated further after the French Grand Prix. Prost believes that Arnoux, who won the race, went back on a pre-race agreement to support Prost during the race. His relationship with the French media was also poor. He has since commented that "When I went to Renault the journalists wrote good things about me, but by 1982 I had become the bad guy. I think, to be honest, I had made the mistake of winning! The French don't really like winners."[20]

In November 1982, three years before it became a round of the F1 World Championship, Prost, along with fellow F1 drivers Jacques Laffite and Nelson Piquet, made the trip to Melbourne, Australia to drive in the non-championship 1982 Australian Grand Prix at the short (1.609 km (1.000 mi)) Calder Park Raceway. Driving a Formula Pacific spec Ralt RT4 powered by a 1.6 litre Ford engine, Prost sat on pole for the race with a time of 39.18. He then led every lap to win what would be the first of 3 Australian Grand Prix wins. He finished 15.32 seconds clear of Laffite, with 1981 AGP winner, young Brazilian driver Roberto Moreno finishing third.

- 1983

Arnoux left Renault in 1983, and American Eddie Cheever replaced him as Prost's partner. Prost earned a further four victories for Renault during the season and finished second in the drivers' championship, two points behind Nelson Piquet. Piquet and the Brabham team overhauled Prost and Renault in the last few races of the season. Prost, who felt the team had been too conservative in developing the car, found himself increasingly at odds with Renault's management, who made him the scapegoat for failing to win a championship. In addition to that, the French fans recalled the bitter fight that had caused their favourite, Arnoux, to leave the team. Prost said in an interview with ESPN during the final race that his car was "not competitive" and that he "didn't lose by my own fault"[22] Renault fired Prost only two days after the South African race. He re-signed for McLaren for the 1984 season within days and moved his family home to Switzerland after Renault factory workers burned the second of 2 of Prost's cars, one of them being a Mercedes-Benz.[20]

1984–1989: Return to McLaren

- 1984

The Frenchman joined double world champion Niki Lauda at McLaren (now being run by Ron Dennis) in 1984, driving the John Barnard designed McLaren MP4/2 which used a 1.5 litre TAG-Porsche V6 engine. He lost the world championship to Lauda in the final race of the season in Portugal by half a point, despite winning seven races to Lauda's five, including winning in Portugal. The half point came from the Monaco Grand Prix, where Prost had been leading, albeit with Ayrton Senna (Toleman) and Stefan Bellof (Tyrrell) closing on him rapidly, when Clerk of the Course Jacky Ickx stopped the race at half distance due to heavy rain, which was controversial as Ickx displayed the red flag without consulting the race officials. Under Formula One regulations, Prost received only half of the nine points normally awarded for a victory.[23]

Prost's seven wins in 1984 equalled the record set by Jim Clark in 1963.

- 1985

.jpg)

In 1985 Prost became the first French Formula One World Champion. He won five of the sixteen Grands Prix during the season. He had also won the San Marino Grand Prix, but was disqualified after his car was found to be 2 kg underweight in post-race scrutineering.[24] Prost finished 20 points ahead of his closest rival, Michele Alboreto. Prost's performance in 1985 earned him the Légion d'honneur distinction in France.

While proud to be the first French World Champion, Prost, annoyed that French journalists were proclaiming it as a win for France, pointed out in interviews that other than himself, nothing about the car (the MP4/2B) had anything to do with France. The team was British (having been founded by a New Zealander), the tyres were American Goodyears, the TAG-Porsche engine was German, the chassis itself was built by Hercules Aerospace in the USA, and was sponsored by an American tobacco company (Marlboro) and the Saudi Arabian owned company Techniques d'Avant Garde (TAG).

- 1986

Niki Lauda retired for good at the end of 1985, and was replaced at McLaren by 1982 World Champion Keke Rosberg for 1986. Prost successfully defended his title, despite his car struggling against the Honda-powered Williams cars driven by Nelson Piquet and Nigel Mansell. Until the latter stages of the final race of the 1986 season, the Australian Grand Prix, Prost appeared set to finish second in the Championship, behind Mansell. Prost had the same number of wins as Piquet, but he had four second places to Piquet's three, thus placing him second before the final race. While running third behind Piquet, and directly behind Prost on the road (3rd was all he needed to win the title), Mansell suffered a rear tyre failure at 180 mph (290 km/h) and crashed out. The Williams team then pitted Piquet to change tyres as a safety precaution, while Prost had already pitted earlier due to a puncture and did not need to change his tyres again. He then held the lead ahead of a charging Piquet to the chequered flag and the Championship.

Another memorable race that year for Prost was at the San Marino Grand Prix. He was cruising to victory when his car began to run out of fuel three corners from the chequered flag. Frantically weaving the car back and forth to slosh the last drops of fuel into the pickup, he managed to keep it running just long enough to creep over the line and win the race (Prost commented after the race that when his car started running dry he immediately thought to himself "shit, I am going to lose this race again", referring to his 1985 disqualification at Imola). It happened again at the German Grand Prix: while running in fourth position, Prost's car ran out of fuel on the finishing straight of the last lap. Instead of retiring at a time in the season when points were critical, Prost got out of his car and tried to push it to the finish, to great applause from the crowd. The finish line was too far, though, and he never reached it. He was eventually classified sixth in the race, as the seventh-placed car (the Brabham-BMW of Derek Warwick) was a lap behind.[25]

- 1987

With Rosberg retiring from Formula One at the end of 1986 season, underrated Swede Stefan Johansson filled the McLaren seat alongside Prost for the 1987 season. Even though McLaren had introduced the new Steve Nichols designed MP4/3 after three seasons with the MP4/2 model (Barnard had departed for Ferrari), the TAG engines were not the force they had been previously, lagging behind in power and with unreliability previously unseen. He never gave up though and challenged Piquet and Mansell almost until the end, winning three races and breaking Jackie Stewart's record for race victories by winning for the 28th time at the Portuguese Grand Prix. Prost considers his win in the opening round in Brazil as his best and most rewarding race ever. The Williams-Hondas had been dominant during qualifying, and Prost started fifth on the grid with a time three seconds slower than Mansell's pole time. Knowing he didn't have the qualifying speed, he instead worked on his race set-up, and with everyone else going for a high-downforce set-up, the Frenchman went the other way. The set-up meant less tyre wear, thanks to slower speeds in the corners while going fast down the straights. With his car having less tyre wear than his rivals, Prost was able to get through the 61 laps of the abrasive Jacarepaguá Circuit with only two stops compared to the three or more by his rivals (Piquet pitted for tyres 3 times within the first 40 laps). Prost finished 40 seconds in front of Piquet, with Johansson a further 16 seconds back in third.

When you win a race like this the feeling is very, very good. There have been times when I have been flat-out to finish sixth, but you can't see that from the outside. In 1980 I finished three or four times in seventh place. I pushed like mad, yet everyone was gathered around the winner and they were thinking that I was just trundling around. But that's motor racing. So in fact the only thing you can judge in this sport is the long term. You can judge a career or a season, but not one race.[26]

Prost finished the 1987 season in fourth place in the championship behind Piquet, Mansell and Lotus driver Ayrton Senna. Prost finished 30 points behind champion Nelson Piquet. Other than his debut season in 1980, and 1991, it was the furthest away he would finish a season from the championship lead.

- 1988

Despite Nelson Piquet winning the 1987 Drivers' Championship and Williams winning the Constructors' Championship, Honda decided not to supply the team with their engines, partly due to Williams' refusal to dump Nigel Mansell and hire Japanese driver and Honda test driver Satoru Nakajima (who debuted with Lotus in 1987), and instead supplied the McLaren team for 1988. Prost had convinced Ron Dennis to sign Ayrton Senna to a three-year contract, which played a role in luring Honda (Senna's ability had been highly regarded by the Japanese giant when using their engines with Lotus in 1987 and both were keen to continue their association). However, this began the rivalry that pushed two of the sport's greatest drivers to unprecedented heights of success and controversy. McLaren-Honda dominated the season, winning 15 out of 16 races. Prost finished first or second in every race other than his two retirements at Silverstone and Monza. He won seven races and in total outscored his new teammate Ayrton Senna by 11 points, despite Senna winning one more race than Prost. However, only the 11 best results from the season counted toward the championship total, and this gave Senna the title by three points. Prost went on to be a proponent of essentially the 1990s scoring system – all results counting to the final results with the winner scoring 10, not 9, points.

In November of that year, Prost had a meeting with the head of Honda's R&D department and F1 racing program, Nobuhiko Kawamoto in Geneva. He expressed his feelings that Honda was giving Senna preferential treatment, and Kawamoto then confirmed Prost's fears, explaining that the Honda engineers were of a new generation, and that they liked Senna's panache and samurai-like driving. Kawamoto was able to convince Prost that he would work something out on the Honda end of the McLaren-Honda partnership for the 1989 season, but this was not to be.[27]

- 1989

McLaren's domination continued throughout 1989, and the Prost-Senna struggle for supremacy put them on a collision course. Mutual admiration turned to all-out hatred, with the Frenchman accusing his Brazilian teammate of "dangerous driving"[28] and of receiving more than a fair share of attention from both McLaren and Honda. For his part, Senna accused Prost of being in the pocket of FISA's French president Jean-Marie Balestre. The animosity between the two drivers came to a head at Round 2 in San Marino. The drivers made an agreement between them that whoever won the start would not be challenged by the other going into the first turn (in this case, the Tosa bend on the Imola circuit). Prost kept to the agreement after Senna won the first start. Prost however won the restart (caused by Gerhard Berger's fiery crash in his Ferrari), but was passed by Senna under brakes for Tosa. Prost went to a friend of his, a French journalist, and told him about the broken agreement between him and Senna. Against Prost's wishes, the journalist went public with the story. During testing at Pembrey in Wales, Senna denied in public any such agreement had ever existed between himself and Prost, but the Frenchman's claim was backed up by Marlboro's John Hogan who had been present when the agreement was made.

Their embittered season ended as many pundits had feared. In the Japanese Grand Prix at the end of lap 46, Senna made his move at the Casino Chicane. Prost, turning into the corner, turned into his teammate's path resulting in a collision and the cars sliding interlocked down the escape road. Prost, thinking the World Championship was over, climbed out of his stalled car. To separate the cars, the marshals pushed Senna's McLaren backwards onto the track. This left it in a dangerous position, so they pushed it forwards again. As they did so, Senna bump-started the engine. He drove through the chicane and rejoined. The nose of his car was damaged and he had to pit, but he rejoined only five seconds behind the Benetton of Alessandro Nannini. On lap 50, Ayrton sliced past Nannini at the chicane to take the lead and won the race. But it was Nannini who appeared on the top step of the podium, race officials having excluded Senna for missing the chicane. McLaren appealed the decision, but the FIA Court of Appeal not only upheld the decision but fined Senna US$100,000 and gave him a suspended six-month ban.[29] Thus Prost clinched his third driver's title in controversial circumstances.

However, Prost had the firm belief that Honda and Ron Dennis viewed Senna as the future of the team. Prost recalled that by the Italian Grand Prix he had one car with maybe four or five mechanics, while his teammate had two cars and 20 people around him.[30] Before the race Prost, who had announced in July 1989 that he would depart from McLaren, announced he was joining Ferrari. Although Prost was forced to make a public apology to both McLaren and Honda over his Monza comments, he received support from Nigel Mansell (who would be his 1990 team mate at Ferrari), and former team mate Rosberg who claimed that once it became known they would not be using the Japanese engines the next season, their Honda engines did not seem to work as well as was once normal. Prost actually won the Italian Grand Prix, after Senna's engine blew with only 9 laps remaining. Until that point Prost's MP4/5 had not been a match for Senna's on Monza's long straights, which had many, especially those in the press, wondering if there was actually truth to Prost's claim that his Honda engines were not as good as the ones Senna was able to use.

As 1989 wore on, Prost continually claimed his Honda V10s were not producing the same amount of power as those in Senna's car. It actually got to the point where Honda F1 boss Osamu Goto felt compelled to speak to the specialist British media on the matter. He claimed that Senna's foot-tapping style with the accelerator helped keep the RA109-E's revs up in the engine's mid-range where most of the power was, while Prost's smoother style dropped the engines into low revs where they had a pick-up problem. Apparently the talk was convincing until most of those present noticed Goto continually called them Ayrton and Prost respectively. An example of Prost's claims came during the Mexican Grand Prix. Despite his car running less wing than Senna's which theoretically would give him greater top speed, Prost's McLaren was not able to pass Senna's on the long front straight even though he came of the final Peraltada Curve clearly faster than the Brazilian and also had the benefit of a tow. In stark contrast, late in the race when Senna was lapping Prost (who was on fresh tyres), Senna was easily able to power past Prost on the straight.

1990–1991: Ferrari

- 1990

The Frenchman replaced Gerhard Berger at Ferrari and was partnered with Britain's Nigel Mansell for 1990 (Berger took Prost's seat at McLaren). As reigning world champion, Prost took over as the team's lead driver and was said to have played on Mansell's inferiority complex. Mansell recalls one incident where at the 1990 British Grand Prix, the car he drove didn't handle the same as in the previous race where he had taken pole position, and later found out from team mechanics that Prost saw Mansell as having a superior car and had them swapped without Mansell knowing.[31] Prost won five races for Ferrari that year, in Brazil, Mexico, France, Britain and Spain. Notable among these was the Mexican Grand Prix, where he won after starting in 13th position. In both the Mexican and Spanish races, he led Mansell to Ferrari 1–2 finishes. The championship once again came to the penultimate round of the season in Japan with Prost trailing his McLaren adversary, Ayrton Senna, by nine points. As in 1989, a controversial collision between the two settled the race. At the first corner Senna, as admitted a year later, intentionally drove his race car into Prost's, taking them both out of the race and sealing the title in his favour.[32] "What he did was disgusting," Prost said. "He is a man without value."[21] Prost finished the season seven points behind Senna, and his Ferrari team were runners-up to McLaren.

- 1991

Mansell left the Scuderia due to his unstable relationship with Prost,[33] to rejoin Williams for the 1991 Formula One season. Mansell's replacement was Frenchman Jean Alesi, who had been impressive during the previous two years at Tyrrell. Ferrari had entered a downturn, partially as their famous V12 engine was no longer competitive against the smaller, lighter and more fuel efficient V10s of their competitors. The Ferrari chassis, despite a major revision by the French Grand Prix (F-643) was also not up to the level of the McLaren and the Williams models. Prost won no races, only getting onto the podium five times. He took this out on the team, publicly criticising the team and the Ferrari 643,[34] and subsequently had his contract terminated before the end of the season, immediately prior to the Australian Grand Prix.[35] He was replaced by Italian driver Gianni Morbidelli for the final race of the 1991 season and by another Italian, Ivan Capelli, for the following season. Despite being sacked, Prost received a significant payment from Ferrari to not drive for any other team.[36]

It was the second time in his career that Alain Prost had been fired by a factory backed team for his public criticism of the team and car, having been fired under similar circumstances by Renault at the end of the 1983 season.

In Japan, the car was like a horrible truck to drive. No pleasure at all. I've underlined the defects of the Ferrari throughout the season, but no-one has listened to a word.— Alain Prost describing the 643 after the 1991 Japanese Grand Prix

1991 was the first time since his debut year in 1980 in which Alain Prost did not win a Formula One Grands Prix.

1993: Williams

Prost went on a sabbatical year in 1992,[37] which was dominated by Nigel Mansell in a Williams-Renault. Prost performed pre-season testing for Ligier early in 1992 and later turned down an offer to drive for the team.[36] After hearing that Prost would be his teammate again in 1993, Mansell left Williams to race in the CART series. The Frenchman had a clause in his contract which prevented rival Ayrton Senna from joining the team that year.[38] Prost was part of a new-look driver line-up at Williams, with test driver Damon Hill coming in to replace Riccardo Patrese, who had left to join Benetton.

Prost won his fourth, and final, title, but in a year where he was regularly challenged by teammate Hill, and Ayrton Senna. Shortly before the Portuguese Grand Prix in October 1993, Prost announced he would not defend his world title, as the clause in the Frenchman's contract did not extend to 1994 and Senna would be able to join Williams for the upcoming season,[38] and instead opted to retire[4] as the driver with the record for most grand prix victories[39] — a record which stood for almost a decade. On the podium in Adelaide in 1993, Prost's last race, he and Senna embraced, and it was as if — now that Prost was no longer a rival — Senna saw no reason for any more hostility. Prost was surprised by the gesture, especially after Senna had declined a shake hands the race before.[40] Prost's performances earned him an OBE.

German Michael Schumacher broke Prost's record of 51 Grand Prix wins during the 2001 season. However, the Frenchman still holds the records for the most Grand Prix starts in turbo powered cars (126), most wins at home Grand Prix (six at the French Grand Prix) and wins with most different teams (4: Renault, McLaren, Ferrari, and Williams). He also shares the record for starting every race of the season from the front row (16 in 1993), with Ayrton Senna in 1989, and Damon Hill in 1996.

He is also thus far the most recent Frenchman to win his home Grand Prix.

Rivalry with Ayrton Senna

Prost's battles with Ayrton Senna were particularly notable. The rivalry originated in 1988, when Senna joined Prost at the McLaren team. The most notable event during the season between the two occurred during the Portuguese Grand Prix, where Senna tried to block Prost from taking the lead by forcing the Frenchman to run close to the pitwall; Prost managed to edge Senna outwards, taking the lead as they went into the first corner but he remained angered by the Brazilian's manoeuvre.[41]

The rivalry intensified after the 1989 San Marino Grand Prix, where the two drivers had an agreement that neither would get in each other's way to the first corner (cf. 1982 San Marino Grand Prix). At the start, Senna got away in the lead and Prost followed him through the first corner without getting in Senna's way. Gerhard Berger's crash on lap four stopped the race. At the restart, it was Prost this time that got away the better of the two; but Senna forced his way past Prost in the first corner, breaking the pair's agreement at the start of the race, leaving the Frenchman furious with Senna. Senna argued it was the restart.[42] Prost himself was angered by McLaren apparently favouring Senna because of Senna's better relationship with engine supplier Honda, so he announced mid-season that he had signed to race for Ferrari the following season.

The rivalry reached its peak at the end of 1989, when the title was to be decided between Senna and Prost at Suzuka. The two McLarens collided at the Casio Triangle chicane when Prost blocked an attempted pass by Senna. Prost walked away while Senna returned to the track. Senna went on to win the race, but was later disqualified in a highly controversial ruling over his path back to the track, as his car was pushed through the road around the chicane. After an unsuccessful appeal by McLaren, the Brazilian received a further US$100,000 fine and a six-month suspension, leading Senna to accuse FIA president Jean-Marie Balestre of favoring his compatriot Prost. Senna's disqualification meant that it was mathematically impossible for him to overhaul Prost's points total, and so the 1989 Championship went to the Frenchman. There has been much debate as to whether Senna was overambitious in his overtaking manoeuver, whether Prost intentionally ran into Senna, or whether the collision was simply a racing incident between two team-mates who were embittered with each other.

The following season saw the two drivers collide again. With Senna leading Prost, now in a Ferrari, in the world drivers' championship, Prost qualified second for the penultimate race of the season in Suzuka with Senna on pole. Between the end of qualifying and race day, pole position was switched to the other side of the track without explanation. Senna complained that no longer being on the racing line, his side of the grid was dirty, meaning he would get less grip and therefore a slower start compared to Prost who had been moved to the clean side of the grid. The Brazilian's appeal was rejected.[43] At the start of the race, Prost got the better start of the two; but whilst braking for the first corner, Senna refused to back off and collided with Prost at 160 mph (260 km/h), clinching the title for the Brazilian.[44] Prost almost retired from the sport, saying "What he did was disgusting. He is a man without value."[21] A year later, Senna admitted that the move was premeditated, in retaliation for the collision at the chicane on the same course the previous year.[32]

There was another controversial incident in 1991. Prost's inferior Ferrari was unable to put up a challenge regularly to Senna's frontrunning McLaren. At the German Grand Prix at Hockenheim, Prost battled Senna for 4th place, however he felt Senna defended too aggressively and at the first chicane forced Prost to take avoiding action by using the escape road. Prost stalled his car rejoining the race. Coincidentally, Senna ran out of fuel on the last lap at the very same point.

The Frenchman took a sabbatical in 1992 after being fired from Ferrari for publicly criticizing the car and the team,[45] while the Brazilian struggled as McLaren was no longer competitive with Williams. Prost announced his signing with Williams for the upcoming 1993 season. Senna had wanted to join Williams too, as they were the most competitive, but Prost had a clause in his contract forbidding the Brazilian as a teammate. An infuriated Senna called the Frenchman a "coward" during a press conference at Estoril, and decried his unwillingness to compete for the drivers' championship on equal sporting terms:

I think if Prost wants to be called the sole champion, three-times world champion, come back in a sportive way, maybe win another championship, he should be sportive. The way he's doing, he's behaving like a coward. And if he wants to be sportive, he must be prepared to race anybody, at any condition, at equal terms.[46]

During the 1993 season, Prost and Senna continued their on-track rivalry. Prost was escorted by police to the Interlagos circuit for the 1993 Brazilian Grand Prix due to the hostility of Brazilians towards him.[47] The two continued their on-track battles at Silverstone where Senna aggressively defended his position against Prost. At Prost's last Grand Prix, the 1993 Australian Grand Prix, he was pulled up by Senna onto the top step of the podium for an embrace.[48]

On 1 May 1994, Ayrton Senna was killed during the San Marino Grand Prix. Prost was a pallbearer at the Brazilian's funeral.[49] Speaking four years after the Brazilian's death, Prost told Nigel Roebuck that he had "always refused to speak about him". When Senna died, Prost stated that "a part of himself had died also", because their careers had been so bound together.[50] Senna had also felt the same when Prost had retired at the end of 1993, when he admitted to a close friend that he had realised how much of his motivation had come from fighting with Prost. Only a couple of days before his death, when filming an in-car lap of Imola for French television channel TF1, he greeted Prost, by then a pundit on the channel: "A special hello to my,... to our dear friend Alain. We all miss you Alain." Prost said that he was amazed and very touched by the comment.[51]

Helmet

Prost uses a helmet design based on the three colours of the French flag, those being blue, white and red, along with his name along the side. During his early career however, Prost used a basic design of white all over with some blue detail around the visor (blue helmet with a white 180° flipped Y and red lines in the lower branch of the flipped Y and in the upper branch, surrounding the top).[52] During Prost's time at Renault, he used more blue details, most notably around the rear of his helmet. Prost's helmet changed in 1985, as his helmet now had the blue detail around the front, surrounding the visor (with also a blue stripe on the side region, making the white area become a P) and a white ring with red lines surrounding the top (forming a white circle with a blue half in the rear of the top). .[53] Prost kept a similar design for his entry at Ferrari and Williams. Sometimes, Prost used variants of his helmet design, in 2007 he used his original design, but with the circle top all red and a red line in the lower chin area. In 2010, he used a pearl white helmet with silver flames and a blue-white-red-white-blue stripe trepassing the visor, designed by kaos design.

Later life

During 1994 and 1995, Prost worked as TV pundit for the French TV channel TF1.[54] He also worked for Renault as a PR man.[54] Prost went back to his old team McLaren, working as a technical advisor; he also completed L'Etape du Tour, an annual mass-participation bike ride that takes place on a stage of the Tour de France.[54] Although not an official race, riders fight hard for places; Prost finished 12th in his category, 42nd overall out of over 5000 riders.[54]

Prost Grand Prix

During 1989 Prost began to contemplate starting his own team, as his relationship with his McLaren teammate, Ayrton Senna, had turned sour. Prost and John Barnard, formerly chief designer at McLaren, came close to founding a team in 1990; but a lack of sponsorship meant that this was not possible, so Prost moved to Ferrari and Barnard left Ferrari to join Benetton. After falling out with the Italian team at the end of 1991, Prost found himself without a drive for 1992; after the failure of extensive negotiations with Guy Ligier about buying his Ligier team, Prost decided to join Williams for 1993.[55] In 1995, when Prost was working for Renault, people began to assume that a Prost-Renault team would be formed in the near future. Renault refused Prost's request to supply engines for his team, ending the speculation.[55]

On 13 February 1997, Prost bought the Ligier team from Flavio Briatore and renamed it "Prost Grand Prix".[56] The day after he bought the team, Prost signed a three-year deal with French car manufacturer Peugeot, who would supply the team with engines from 1998 until 2000.[56] For the team's first season, Prost kept one of Ligier's 1996 drivers, Olivier Panis, who had won the Monaco Grand Prix the previous year; Japanese driver Shinji Nakano was signed to partner Panis. The team raced with the Mugen-Honda engines used by Ligier the previous season, while the car was actually the originally intended Ligier JS45, but was renamed the Prost JS45. Things looked promising at the start of the season, as the team picked up two points on its Grand Prix debut in Australia when Olivier Panis finished fifth. The team scored a further 13 points before Panis broke his leg in an accident during the Canadian Grand Prix. He was replaced by Minardi's Jarno Trulli. From there, things started to go downhill slightly, the team scored only five points during Panis' recovery. The Frenchman came back at the end of the season to race the final three Grand Prix. Prost GP finished sixth in the constructors' championship in its first season, with 21 points.

Prost became the president of Prost Grand Prix at the start of 1998. With Peugeot supplying the engines for Prost GP, Mugen-Honda decided to supply the Jordan team. Prost GP scored a single point during the season, Jarno Trulli finishing sixth in Belgium.

1999 was a crucial year for Prost GP.[57] Prost hired John Barnard as a technical consultant,[56] Barnard's B3 Technologies company helping Loic Bigois and the design of the Prost AP02. Panis and Trulli agreed to stay on with the team for the season. While the car did not prove to be a major concern, the Peugeot V10 engine proved to be heavy and unreliable.

Peugeot's final year as Prost's engine supplier in 2000 saw some optimism, Prost hiring his 1991 Ferrari team mate Jean Alesi to drive the lead car and German Nick Heidfeld, who had won the 1999 Formula 3000 championship, to partner him. The season proved to be yet another disastrous one, with the AP03 proving to be unreliable and ill handling. Things weren't helped when both drivers collided with each other in the Austrian Grand Prix. Newly hired technical director Alan Jenkins was fired midway through the year. Prost restructured the team, hiring Joan Villadelprat as the managing director and replacing Jenkins with Henri Durand as the team's new technical director.[56]

2001 saw some much needed optimism for the team as Ferrari agreed to be the team's engine supplier for the season, the team now moving in the right direction.[56] But the money ran out at the start of the 2002 season and Prost was out of business, leaving debts of around $30 million.[56]

After Prost Grand Prix

During 2002, Prost spent time with his family and competed in eight bicycle races, finishing third in the Granite – Mont Lozère.[58] The Frenchman raced in the Andros ice race series in 2003, finishing second in the championship behind Yvan Muller;[59] he also became an Ambassador for Uniroyal, a position he would keep until May 2006.[54]

Prost continued to compete in the Andros Trophy, winning the title with Toyota in 2006/07, 2007/08 and with Dacia in 2011/2012.[60][61][62]

For the 2010 Formula One season, the Sporting Regulations were changed so that a former driver sits on the stewards' panel. Prost was the first such driver to take on this role, at the 2010 Bahrain Grand Prix.[63] Prost also took part in the Race of Champions in 2010, a race organised for legends of motor sport to compete in equal machinery.

In February 2012, Prost was named as Renault's new international ambassador, representing the company in sports demonstrations and at events organized or attended by Renault.[64]

Prost has finished the Absa Cape Epic, an eight-day 700 km mountain bike race in South Africa, twice. He first completed the race in 2012 with partner Sebastien di Pasqua and then again in 2013, and started but did not finish the race in 2014.[65]

In October 2013 it was announced that Prost would join forces with Jean-Paul Driot's DAMS racing team to form e.dams, a team which would compete in the FIA Formula E Championship for electric racing cars from its commencement in September 2014.[66] In June 2014 the team announced that its initial driver line-up would consist of Nicolas Prost and Sébastien Buemi.[67] The team went on to win the inaugural Formula E teams championship.[68]

Racing record

Complete Formula One World Championship results

(key) (Races in bold indicate pole position, races in italics indicate fastest lap)

- ‡ Race was stopped with less than 75% of laps completed, half points awarded.

Formula One non-championship results

(key) (Races in bold indicate pole position) (Races in italics indicate fastest lap)

| Year | Entrant | Chassis | Engine | 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | Marlboro Team McLaren | McLaren M29 | Ford Cosworth DFV | ESP Ret |

References

- 1 2 Up until 1990, not all points scored by a driver contributed to their final World Championship tally (see list of points scoring systems for more information). Numbers without parentheses are Championship points; numbers in parentheses are total points scored.

- ↑ "Ali, Pele and Carl Lewis Honored at World Sports Awards of the Century Gala". Jet. Johnson Publishing Company: 50. 13 December 1999.

- ↑ Prostfan.com – Profile. Retrieved 8 March 2008.

- 1 2 "Prost, 38, Announces Retirement", Los Angeles Times, 25 September 1993

- ↑ "Press Release - ALAIN PROST TO MAKE RACING COMEBACK WITH TOYOTA". pressroom.com.au. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ↑ "Andros Trophy: Without Dacia and Alain Prost - Auto123.com". auto123.com. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ↑ "trophee - statistiques pilotes". tropheeandros.com. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ↑ Roebuck, Nigel (1986) Grand Prix Greats p. 131 Book Club Associates ISBN 0-85059-792-7

- ↑ Hall of Fame — Alain Prost, Formula1.com. Paragraph 6. Retrieved 16 August 2006.

- ↑ Alain's Biography (1921–54), ProstFan.com. Retrieved 22 November 2006.

- ↑ Alain Prost Siblings, ProstFan.com. Retrieved 25 September 2006.

- ↑ Hall of Fame — Alain Prost, Formula1.com. Paragraph 2. Retrieved 16 August 2006.

- ↑ Hall of Fame — Alain Prost, Formula1.com. Paragraph 1. Retrieved 16 August 2006.

- ↑ – Nicolas' career year by year, 2003 – 2008, ProstFan.com. Retrieved 24 March 2008.

- 1 2 McBride, Stewart (8 November 1987). "Racing's Record Breaker". New York Times. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- ↑ "Alain Prost Information". prostfan.com. Retrieved 17 August 2006.

- ↑ There were several national Formula Renault championships in Europe.

- 1 2 Alain Prost, GrandPrix.com. Retrieved October 2006.

- 1 2 Roebuck, Nigel Grand Prix Greats 1986, p. 126. Book Club Associates ISBN 0-85059-792-7

- 1 2 3 Roebuck, Nigel Grand Prix Greats 1986, p. 129. Book Club Associates ISBN 0-85059-792-7

- 1 2 3 Hall of Fame — Alain Prost, formula1.com. Retrieved 7 October 2006.

- ↑ Video on YouTube

- ↑ Prost wins under a cloud of controversy, GPRacing.net192.com. Retrieved 30 October 2014.

- ↑ "1985 San Marino Grand Prix". GPRacing.net192.com. Archived from the original on July 22, 2006. Retrieved 7 October 2006.

- ↑ "Grand Prix Results: German GP, 1986". GrandPrix.com. Archived from the original on 9 November 2006. Retrieved 7 November 2006.

- ↑ transcript of recording from Forix.com, paragraphs 19 & 20.

- ↑ AutoDocumentary. "F1 Legends - Alain Prost". Dailymotion.

- ↑ "Hall of Fame – Alain Prost". Formula1.com Paragraph 7. Retrieved 16 August 2006.

- ↑ "Grand Prix Results: Japanese GP, 1989". GrandPrix.com. Retrieved 16 August 2006.

- ↑ Senna, Ayrton (1 October 1998). "Ayrton Senna – by Alain Prost". MOTOR SPORT (Interview). Interview with Alain Prost. prostfan.com. Retrieved 18 May 2009.

- ↑ Mansell, Nigel My Autobiography page 222 Collins Willow ISBN 0-00-218497-4

- 1 2 Ayrton Senna attacks Jean-Marie Balestre, GrandPrix.com. Retrieved 11 October 2006.

- ↑ Murray Walker & Simon Taylor Murray Walker's Formula One Heroes p. 108, paragraph 2. Virgin Books, ISBN 1-85227-918-4

- ↑ Zapelloni, Umberto (April 2004). Formula Ferrari. Hodder & Stoughton. p. 17. ISBN 0-340-83471-4.

- ↑ Murray Walker & Simon Taylor, Murray Walker's Formula One Heroes p. 115, lines 6–9. Virgin Books, ISBN 1-85227-918-4

- 1 2 Diepraam, Mattijs; Nyberg, Rainer (May 2001). "Subtlety redefined". 8w.forix. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ↑ "Hall of Fame — Alain Prost". Formula1.com, paragraph 9. Retrieved 16 August 2006.

- 1 2 Menard and Vassal (2003), p. 138.

- ↑ "Grand Prix Results: Portuguese GP, 1993". GrandPrix.com. Archived from the original on 30 October 2006. Retrieved 7 November 2006.

- ↑ "Ayrton Senna by Alain Prost". ProstFan.com, paragraph 50. Retrieved 12 October 2006.

- ↑ Grand Prix Results: Portuguese GP, 1988, GrandPrix.com. Retrieved 17 August 2006.

- ↑ Hughes, Mark. The Unofficial Complete Encyclopedia Of Formula One. Hermes House. pp. 72, lines 13–27. ISBN 1-84309-864-4.

- ↑ Hughes, Mark. The Unofficial Complete Encyclopedia Of Formula One. Hermes House. pp. 75, lines 8–17. ISBN 1-84309-864-4.

- ↑ Hughes, Mark. The Unofficial Complete Encyclopedia of Formula One. Hermes House. pp. 75, lines 18–29. ISBN 1-84309-864-4.

- ↑ "Prost: Schumacher is better than me". BBC News. Retrieved 16 September 2012.

- ↑ "Ayrton Senna Calls Prost A Coward.mpg". Youtube.com. Retrieved 28 June 2013.

This is supposed to be a world drivers' championship!

- ↑ Allsop, Derick. Designs on Victory: On the Grand Prix Trail With Benetton. Hutchinson. ISBN 0-09-178311-9.

- ↑ "Fan review of Grand Prix with image of pair on podium". farzadsf1gallery.com. Archived from the original on 25 October 2006. Retrieved 28 January 2007.

- ↑ "Open Warfare". GPRacing.net192.com. Archived from the original on 2 July 2007. Retrieved 30 August 2015.

- ↑ Ayrton Senna — By Alain Prost, ProstFan.com. Paragraph 3. Retrieved 16 August 2006.

- ↑ Hamilton, Maurice. Frank Williams. Macmillan. p. 234. ISBN 0-333-71716-3.

- ↑ Grande Prěmio da Argentina de 1980 LookWeb.com.br. Retrieved 12 October 2006.

- ↑ Alain Prost Helmet JmJauto.com. Retrieved 12 October 2006.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Alain Prost Information – Alain's career year by year, 1973–2006 ProstFan.com. Retrieved 11 October 2006.

- 1 2 Team Prost – a dream or reality? GrandPrix.com. Retrieved 12 October 2006.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 GrandPrix.com – GP Encyclopedia – Constructor – Prost Grand Prix GrandPrix.com. Retrieved 8 September 2006.

- ↑ Jean-Michel Desnoues; Patrick Camus & Jean-Marc Loubat Formula 1 99 . Queen Anne Press. ISBN 1-85291-606-0

- ↑ Alain Prost 2002 Bicycle Racing, ProstFan.com. Retrieved 11 October 2006.

- ↑ Trophée Andros Championship Standings, p. 3. ProstFan.com. Retrieved 11 October 2006.

- ↑ Trophée Andros Championship Standings, p. 4. ProstFan.com. Retrieved 11 October 2006.

- ↑ Trophée Andros Championship Standings, p. 5. ProstFan.com. Retrieved 11 October 2006.

- ↑ Trophée Andros, ProstFan.com. Retrieved 11 October 2006.

- ↑ Beer, Matt (11 March 2010). "Prost joins stewards for Bahrain". autosport.com. Haymarket Publications. Retrieved 11 March 2010.

- ↑ Vandezande, Luke (23 February 2012). "Alain Prost Named New Renault Brand Embassador". AutoGuide. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ↑ "Absa Cape Epic Website". Retrieved 29 October 2012.

- ↑ "Alain Prost & Jean-Paul Driot team up for Formula E". FIA Formula E Championship. 24 October 2013. Retrieved 28 June 2015.

- ↑ "Buemi & Prost sign for newly-titled e.dams-Renault". FIA Formula E Championship. 30 June 2014. Retrieved 28 June 2015.

- ↑ Baldwin, Alan (28 June 2015). Ferris, Ken, ed. "Renault to invest more in electric series". reuters.com. Retrieved 28 June 2015.

Further reading

- Alan Henry, Alain Prost (Champion Series) ISBN 0-946132-30-5

- Pierre Ménard and Jacques Vassal, Alain Prost: The Science of Racing (Formula 1 Legends S.) ISBN 2-84707-062-1

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Alain Prost. |

- Alain Prost – fan page: interviews, photos, statistics, regularly updated

- Grand Prix History – Hall of Fame

- Alain Prost statistics

- Alain Prost Biography – McLaren

All Formula One race and championship results are taken from:

- Official Formula One website, Results for 1980–93 seasons. Retrieved 16 August 2006.

- Official Formula One website, Results for 1997–2001 seasons. Retrieved 17 August 2006.