Deneb

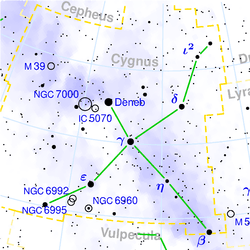

Cygnus, the constellation in which Deneb is located. | |

| Observation data Epoch J2000 Equinox J2000 | |

|---|---|

| Constellation | Cygnus |

| Right ascension | 20h 41m 25.9s[1] |

| Declination | +45° 16′ 49″[1] |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | 1.25[2] (1.21 - 1.29[3]) |

| Characteristics | |

| Spectral type | A2 Ia[4] |

| U−B color index | −0.23[2] |

| B−V color index | +0.09[2] |

| Variable type | Alpha Cyg[3] |

| Astrometry | |

| Radial velocity (Rv) | −4.5[5] km/s |

| Proper motion (μ) | RA: 1.99[1] mas/yr Dec.: 1.95[1] mas/yr |

| Parallax (π) | 2.29 ± 0.32[1] mas |

| Distance | 802 ± 66[6] pc |

| Absolute magnitude (MV) | −8.38[6] |

| Details | |

| Mass | 19 ± 4[6] M☉ |

| Radius | 203 ± 17[6] R☉ |

| Luminosity | 196,000 ± 32,000[6] L☉ |

| Surface gravity (log g) | 1.10 ± 0.05[6] cgs |

| Temperature | 8,525 ± 75[6] K |

| Metallicity [Fe/H] | -0.25[6] dex |

| Rotational velocity (v sin i) | 20 ± 2[6] km/s |

| Other designations | |

| Database references | |

| SIMBAD | data |

Deneb (/ˈdɛnɛb/), also designated Alpha Cygni (α Cygni, abbreviated Alpha Cyg, α Cyg), is the brightest star in the constellation of Cygnus. It is one of the vertices of the asterism known as the Summer Triangle and forms the 'head' of the Northern Cross. It is the 19th brightest star in the night sky, with an apparent magnitude of 1.25. A blue-white supergiant, Deneb is also one of the most luminous stars. However, its exact distance (and hence luminosity) has been difficult to calculate; it is estimated to be somewhere between 55,000 and 196,000 times as luminous as the Sun.[7]

Nomenclature

α Cygni (Latinised to Alpha Cygni) is the star's Bayer designation. The traditional name Deneb is derived from dhaneb, Arabic for "tail", from the phrase ذنب الدجاجة Dhanab ad-Dajājah, or "tail of the hen".[8] In 2016, the International Astronomical Union organized a Working Group on Star Names (WGSN)[9] to catalog and standardize proper names for stars. The WGSN's first bulletin of July 2016[10] included a table of the first two batches of names approved by the WGSN; which included Deneb for this star. It is now so entered in the IAU Catalog of Star Names.[11]

Visibility

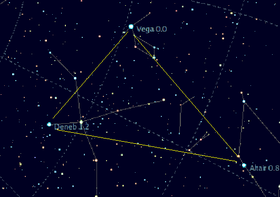

Deneb lies at one vertex of a widely spaced asterism called the Summer Triangle, the other two members of which are the zero-magnitude stars Vega in the constellation Lyra and Altair in Aquila.[12] This formation is the approximate shape of a right triangle, with Deneb located at one of the acute angles. The Summer Triangle is recognizable in the northern skies for there are few other bright stars in its vicinity.[13]

Deneb is also easily spotted as the tip of the Northern Cross asterism made up of the brightest stars in Cygnus, the others being Beta (Albireo), Gamma, Delta, and Epsilon Cygni.[14] It never dips below the horizon at or above 45° north latitude, just grazing the northern horizon at its lowest point at such locations as Minneapolis, Montréal and Turin.

In the northern hemisphere Deneb is high in the sky during summer evenings.[14]

In the southern hemisphere, Deneb is not at all visible south of 45° south parallel, so it just barely rises above the horizon in Tasmania and southern New Zealand during the southern winter (which corresponds to the northern summer).

Pole star

Due to the Earth's axial precession, Deneb will become the Pole star at around 9800 AD.[15]

Distance and properties

Deneb's exact distance from the Earth is still rather uncertain. The currently accepted distance of around 2,600 light-years (and the associated physical data shown in the starbox) is derived by a variety of methods, including spectral luminosity classes, atmospheric modelling, stellar evolution models, assumed membership of the Cygnus OB7 association, and direct measurements of angular diameter. The original rather inaccurate Hipparcos parallax measurement[16][17] was not inconsistent with this distance, but the more recent re-analysis[1] gives a much larger parallax and a distance barely half the widely accepted value. One 2008 calculation using the Hipparcos data[18] puts the most likely distance at 1,550 light-years, with an uncertainty of only around 10%, although parallax measurements of asymmetric, pulsating stars embedded within shells are known to be unreliable. The controversy over whether the direct Hipparcos measurements can be ignored in favour of a wide range of indirect stellar models and interstellar distance scales is similar to the better known situation with the Pleiades.[1] The Gaia satellite should provide distance measurements at least two orders of magnitude more reliable than Hipparcos and resolve many such questions, although it will not measure Deneb itself.[19]

Deneb's absolute magnitude is currently estimated as −8.4, placing it among the most luminous stars known, with an estimated luminosity nearly 200,000 times that of the Sun. This is towards the upper end of various published values over the last few decades.[7][20][21]

Deneb is the most luminous of the stars with apparent magnitude brighter than 1.5, and the most distant, by a factor of almost 2, of the 30 brightest stars. Based on its temperature and luminosity, and also on direct measurements of its tiny angular diameter (a mere 0.002 second of arc), Deneb appears to have a diameter of about over 200 times that of the Sun;[7] if placed at the center of the Solar System, Deneb would extend out to the orbit of the Earth. It is one of the largest white stars.

Deneb is a bluish-white star of spectral type A2Ia, with a surface temperature of 8,500 kelvin. Since 1943, its spectrum has served as one of the stable anchor points by which other stars are classified.[4] It is the prototype of a class of variable stars known as Alpha Cygni variables. Its surface undergoes non-radial fluctuations which cause its brightness to vary by up to 0.15 magnitude with no clear periodicity, and the spectral type to change slightly.[22]

Deneb's mass is estimated at 19 solar masses (M☉). Its stellar wind causes it to lose mass at a rate of 8±3×10−7 M☉ per year, one hundred thousand times the flow rate from the Sun.[23]

Binary companion

Deneb has been reported as a possible single line spectroscopic binary, where the radial velocity of the spectral lines from the primary star changes in a periodic fashion, but no spectral features from a companion are seen.[24] More detailed analysis of the spectrum over time has not found any support for this.[22]

Evolutionary state

Deneb spent much of its early life as a 23 M☉ O-type main-sequence star but it has now exhausted the supply of hydrogen in its core and begun to cool and expand.[6] Stars in the mass range of Deneb eventually expand to become the most luminous red supergiants, and within a few million years their cores will collapse producing a supernova explosion. It is now known that red supergiants up to a certain mass explode as the commonly seen type II-P supernovae, but more massive ones lose their outer layers to become hotter again. Depending on their initial masses and the rate of mass loss, they may explode as yellow hypergiants or luminous blue variables, or they may become Wolf-Rayet stars before exploding in a type Ib or Ic supernova. Identifying whether Deneb is currently evolving towards a red supergiant or is currently evolving bluewards again would place valuable constraints on the classes of stars that explode as red supergiants and those that explode as hotter stars.[25]

Stars evolving redwards for the first time are most likely fusing hydrogen in a shell around a helium core that has not yet grown hot enough to start fusion to carbon and oxygen. Convection has begun to dredge up the products of fusion but these are not visible at the surface. Post-red supergiant stars are expected to show those fusion products at the surface due to stronger convection during the red supergiant phase and due to loss of the obscuring outer layers of the star. Deneb is thought to be evolving redwards, although current models do not exactly reproduce the surface elements showing in its spectrum.[25]

Etymology and cultural significance

Names similar to Deneb were given to at least seven different stars, most notably Deneb Kaitos, the brightest star in the constellation of Cetus; Deneb Algedi, the brightest star in Capricornus; and Denebola, the second brightest star in Leo. All these stars are referring to the tail of the animals that their respective constellations represent.

Denebadigege was used in the Alfonsine Tables,[26] other variants include Deneb Adige, Denebedigege and Arided. This latter name was derived from Al Ridhādh, a name for the constellation. Johann Bayer called it Arrioph, derived from Aridf and Al Ridf, 'the hindmost' or Gallina. German poet and author Philippus Caesius termed it Os rosae, or Rosemund in German, or Uropygium – the parson's nose.[8] The names Arided and Aridif have fallen out of use.

In Chinese, 天津 (Tiān Jīn), meaning Celestial Ford, refers to an asterism consisting of Deneb, γ Cygni, δ Cygni, 30 Cygni, ν Cygni, τ Cygni, υ Cygni, ζ Cygni and ε Cygni.[27] Consequently, Deneb itself is known as 天津四 (Tiān Jīn sì, English: the Fourth Star of the Celestial Ford).[28]

In the Chinese love story of Qi Xi, Deneb marks the magpie bridge across the Milky Way, which allows the separated lovers Niu Lang (Altair) and Zhi Nü (Vega) to be reunited on one special night of the year in late summer. In other versions of the story Deneb is a fairy who acts as chaperone when the lovers meet.

The north pole of Mars points to the midpoint of the line connecting Deneb and the star Alderamin.[29]

Namesakes

USS Arided was a United States Navy Crater-class cargo ship named after the star.

Deneb in fiction

The star Deneb, and hypothetical planets orbiting it, have been used many times in literature, film, electronic games, and music. Examples include several episodes of the Star Trek TV series, the Silver Surfer comic book, the Rush albums A Farewell to Kings and Hemispheres, the Descent: FreeSpace – The Great War computer game, Stellaris (video game), science fiction novel Hyperion, and Andy Weir, in his novel The Martian.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 van Leeuwen, F. (2009). "The Hipparcos catalog". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 500: 505–506. Bibcode:2009A&A...500..505V. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/200912202.

- 1 2 3 Ducati, J. R. (2002). "VizieR Online Data Catalog: Catalogue of Stellar Photometry in Johnson's 11-color system". CDS/ADC Collection of Electronic Catalogues. 2237: 0. Bibcode:2002yCat.2237....0D.

- 1 2 Samus, N. N.; Durlevich, O. V.; et al. (2009). "VizieR Online Data Catalog: General Catalogue of Variable Stars (Samus+ 2007–2013)". VizieR On-line Data Catalog: B/gcvs. Originally published in: 2009yCat....102025S. 1: 02025. Bibcode:2009yCat....102025S.

- 1 2 Garrison, R. F. (1993). "Anchor Points for the MK System of Spectral Classification". Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society. 25: 1319. Bibcode:1993AAS...183.1710G. Retrieved 2012-02-04.

- ↑ Gontcharov, G. A. (2006). "Pulkovo Compilation of Radial Velocities for 35 495 Hipparcos stars in a common system". Astronomy Letters. 32 (11): 759. Bibcode:2006AstL...32..759G. doi:10.1134/S1063773706110065.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Schiller, F.; Przybilla, N. (2008). "Quantitative spectroscopy of Deneb". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 479 (3): 849–858. arXiv:0712.0040

. Bibcode:2008A&A...479..849S. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20078590.

. Bibcode:2008A&A...479..849S. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20078590. - 1 2 3 Chesneau, O.; Dessart, L.; Mourard, D.; Bério, Ph.; Buil, Ch.; Bonneau, D.; Borges Fernandes, M.; Clausse, J. M.; Delaa, O.; Marcotto, A.; Meilland, A.; Millour, F.; Nardetto, N.; Perraut, K.; Roussel, A.; Spang, A.; Stee, P.; Tallon-Bosc, I.; McAlister, H.; Ten Brummelaar, T.; Sturmann, J.; Sturmann, L.; Turner, N.; Farrington, C.; Goldfinger, P. J. (2010). "Time, spatial, and spectral resolution of the Hα line-formation region of Deneb and Rigel with the VEGA/CHARA interferometer". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 521: A5. arXiv:1007.2095

. Bibcode:2010A&A...521A...5C. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201014509.

. Bibcode:2010A&A...521A...5C. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201014509. - 1 2 Allen, R. H. (1963). Star Names: Their Lore and Meaning (Reprint ed.). Dover Publications. p. 195. ISBN 0-486-21079-0.

- ↑ "IAU Working Group on Star Names (WGSN)". Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- ↑ "Bulletin of the IAU Working Group on Star Names, No. 1" (PDF). Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- ↑ "IAU Catalog of Star Names". Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- ↑ Pasachoff, J. M. (2000). A Field Guide to Stars and Planets (4th ed.). Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-93431-1.

- ↑ Upgren, A. R. (1998). Night Has a Thousand Eyes: A Naked-Eye Guide to the Sky, Its Science, and Lore. Basic Books. ISBN 0-306-45790-3.

- 1 2 Smith, C. E. (1937). "Stars of the Summer Sky". Astronomical Society of the Pacific Leaflets. 3: 23. Bibcode:1937ASPL....3...23S.

- ↑ "Deneb". June 19, 1998. Retrieved November 29, 2015.

- ↑ Perryman, M. A. C.; Lindegren, L.; Kovalevsky, J.; Hoeg, E.; Bastian, U.; Bernacca, P. L.; Crézé, M.; Donati, F.; Grenon, M.; Grewing, M.; Van Leeuwen, F.; Van Der Marel, H.; Mignard, F.; Murray, C. A.; Le Poole, R. S.; Schrijver, H.; Turon, C.; Arenou, F.; Froeschlé, M.; Petersen, C. S. (1997). "The Hipparcos Catalogue". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 323: L49–L52. Bibcode:1997A&A...323L..49P.

- ↑ Perryman, M. (2010). The Making of History's Greatest Star Map. Springer-Verlag. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-11602-5. ISBN 978-3-642-11601-8.

- ↑ Maíz Apellániz, J.; Alfaro, E. J.; Sota, A. (2008). "Accurate distances to nearby massive stars with the new reduction of the Hipparcos raw data". 0804: 2553. arXiv:0804.2553

[astro-ph]. Bibcode:2008arXiv0804.2553M.

[astro-ph]. Bibcode:2008arXiv0804.2553M. - ↑ Turon, Catherine; Luri, Xavier; Masana, Eduard (2012). "Building the cosmic distance scale: From Hipparcos to Gaia". Astrophysics and Space Science. 341: 15. arXiv:1202.3645

. Bibcode:2012Ap&SS.341...15T. doi:10.1007/s10509-012-1026-5.

. Bibcode:2012Ap&SS.341...15T. doi:10.1007/s10509-012-1026-5. - ↑ van de Kamp, P. (1953). "The Twenty Brightest Stars". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 65: 30. Bibcode:1953PASP...65...30V. doi:10.1086/126523.

- ↑ Lamers, H. J. G. L. M.; Stalio, R.; Kondo, Y. (1978). "A study of mass loss from the mid-ultraviolet spectrum of α Cygni (A2 Ia), β Orionis (B8 Ia), and η Leonis (A0 Ib)". The Astrophysical Journal. 223: 207. Bibcode:1978ApJ...223..207L. doi:10.1086/156252.

- 1 2 Richardson, N. D.; Morrison, N. D.; Kryukova, E. E.; Adelman, S. J. (2011). "A Five-year Spectroscopic and Photometric Campaign on the Prototypical α Cygni Variable and A-type Supergiant Star Deneb". The Astronomical Journal. 141: 17. arXiv:1009.5994

. Bibcode:2011AJ....141...17R. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/141/1/17.

. Bibcode:2011AJ....141...17R. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/141/1/17. - ↑ Aufdenberg, J. P.; Hauschildt, P. H.; Baron, E.; Nordgren, T. E.; Burnley, A. W.; Howarth, I. D.; Gordon, K. D.; Stansberry, J. A. (2002). "The Spectral Energy Distribution and Mass-Loss Rate of the A-Type Supergiant Deneb". The Astrophysical Journal. 570: 344. arXiv:astro-ph/0201218

. Bibcode:2002ApJ...570..344A. doi:10.1086/339740.

. Bibcode:2002ApJ...570..344A. doi:10.1086/339740. - ↑ Lucy, L. B. (1976). "An analysis of the variable radial velocity of alpha Cygni". Astrophysical Journal. 206: 499. Bibcode:1976ApJ...206..499L. doi:10.1086/154405.

- 1 2 Georgy, Cyril; Saio, Hideyuki; Meynet, Georges (2014). "The puzzle of the CNO abundances of α Cygni variables resolved by the Ledoux criterion". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society: Letters. 439: L6. arXiv:1311.4744

. Bibcode:2014MNRAS.439L...6G. doi:10.1093/mnrasl/slt165.

. Bibcode:2014MNRAS.439L...6G. doi:10.1093/mnrasl/slt165. - ↑ Kunitzsch, P. (1986). "The Star Catalogue Commonly Appended to the Alfonsine Tables". Journal for the History of Astronomy. 17 (49): 89–98. Bibcode:1986JHA....17...89K.

- ↑ (Chinese) 中國星座神話, written by 陳久金. Published by 台灣書房出版有限公司, 2005, ISBN 978-986-7332-25-7.

- ↑ (Chinese) 香港太空館 - 研究資源 - 亮星中英對照表, Hong Kong Space Museum. Accessed on line November 23, 2010.

- ↑ Barlow, N. G. (2008). Mars: An introduction to its interior, surface and atmosphere. Cambridge University Press. p. 21. ISBN 0-521-85226-9.

Coordinates: ![]() 20h 41m 25.9s, +45° 16′ 49″

20h 41m 25.9s, +45° 16′ 49″