Angkor Thom

| Angkor Thom | |

|---|---|

|

Gateway to Angkor Thom[2] | |

Angkor Thom Location within Cambodia | |

| Name | |

| Proper name | Prasat Angkor Thom |

| Geography | |

| Coordinates | 13°24′45″N 103°52′0″E / 13.41250°N 103.86667°ECoordinates: 13°24′45″N 103°52′0″E / 13.41250°N 103.86667°E |

| Country | Cambodia |

| Locale | Angkor, Siem Reap Province, Cambodia |

| Architecture | |

| Architectural styles | Khmer, Dravidian |

| History and governance | |

| Date built | 12th century |

| Creator | Jayavarman VII |

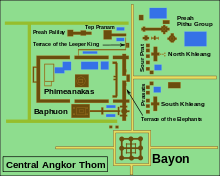

Angkor Thom (Khmer: អង្គរធំ; literally: "Great City"), located in present-day Cambodia, was the last and most enduring capital city of the Khmer empire. It was established in the late twelfth century by King Jayavarman VII.[3]:378–382[4]:170 It covers an area of 9 km², within which are located several monuments from earlier eras as well as those established by Jayavarman and his successors. At the centre of the city is Jayavarman's state temple, the Bayon, with the other major sites clustered around the Victory Square immediately to the north.

Angkor Thom was established as the capital of Jayavarman VII's empire, and was the centre of his massive building programme. One inscription found in the city refers to Jayavarman as the groom and the city as his bride.[5]:121

Angkor Thom seems not to be the first Khmer capital on the site, however. Yasodharapura, dating from three centuries earlier, was centred slightly further northwest, and Angkor Thom overlapped parts of it. The most notable earlier temples within the city are the former state temple of Baphuon, and Phimeanakas, which was incorporated into the Royal Palace. The Khmers did not draw any clear distinctions between Angkor Thom and Yashodharapura: even in the fourteenth century an inscription used the earlier name.[5]:138 The name of Angkor Thom—great city—was in use from the 16th century.

The last temple known to have been constructed in Angkor Thom was Mangalartha, which was dedicated in 1295. Thereafter the existing structures continued to be modified from time to time, but any new creations were in perishable materials and have not survived.

The Ayutthaya Kingdom, led by King Borommarachathirat II, sacked Angkor Thom, forcing the Khmers under Ponhea Yat to relocate their capital southeast.[6]:29

Angkor Thom was abandoned some time prior to 1609, when an early western visitor wrote of an uninhabited city, "as fantastic as the Atlantis of Plato".[5]:140 It is believed to have sustained a population of 80,000–150,000 people.

Style

Angkor Thom is in the Bayon style. This manifests itself in the large scale of the construction, in the widespread use of laterite, in the face-towers at each of the entrances to the city and in the naga-carrying giant figures which accompany each of the towers.

The site

The city lies on the west bank of the Siem Reap River, a tributary of Tonle Sap, about a quarter of a mile from the river. The south gate of Angkor Thom is 7.2 km north of Siem Reap, and 1.7 km north of the entrance to Angkor Wat. The walls, 8 m high and flanked by a moat, are each 3 km long, enclosing an area of 9 km². The walls are of laterite buttressed by earth, with a parapet on the top. There are gates at each of the cardinal points, from which roads lead to the Bayon at the centre of the city. As the Bayon itself has no wall or moat of its own, those of the city are interpreted by archaeologists as representing the mountains and oceans surrounding the Bayon's Mount Meru.[7]:81 Another gate—the Victory Gate—is 500 m north of the east gate; the Victory Way runs parallel to the east road to the Victory Square and the Royal Palace north of the Bayon.

The faces on the 23 m towers at the city gates, which are later additions to the main structure, take after those of the Bayon and pose the same problems of interpretation. They may represent the king himself, the bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara, guardians of the empire's cardinal points, or some combination of these. A causeway spans the moat in front of each tower: these have a row of devas on the left and asuras on the right, each row holding a naga in the attitude of a tug-of-war. This appears to be a reference to the myth, popular in Angkor, of the Churning of the Sea of Milk. The temple-mountain of the Bayon, or perhaps the gate itself,[7]:82 would then be the pivot around which the churning takes place. The nagas may also represent the transition from the world of men to the world of the gods (the Bayon), or be guardian figures.[8] The gateways themselves are 3.5 by 7 m, and would originally have been closed with wooden doors.[7]:82 The south gate is now by far the most often visited, as it is the main entrance to the city for tourists.

At each corner of the city is a Prasat Chrung—corner shrine—built of sandstone and dedicated to Avalokiteshvara. These are cruciform with a central tower, and orientated towards the east.

Within the city was a system of canals, through which water flowed from the northeast to the southwest. The bulk of the land enclosed by the walls would have been occupied by the secular buildings of the city, of which nothing remains. This area is now covered by forest.

Most of the great Angkor ruins have vast displays of bas-relief depicting the various gods, goddesses, and other-worldly beings from the mythological stories and epic poems of ancient Hinduism (modified by centuries of Buddhism). Mingled with these images are actual known animals, like elephants, snakes, fish, and monkeys, in addition to dragon-like creatures that look like the stylized, elongated serpents (with feet and claws) found in Chinese art.

But among the ruins of Ta Prohm, near a huge stone entrance, one can see that the "roundels on pilasters on the south side of the west entrance are unusual in design."

What one sees are roundels depicting various common animals—pigs, monkeys, water buffaloes, roosters and snakes. There are no mythological figures among the roundels, so one can reasonably conclude that these figures depict the animals that were commonly seen by the ancient Khmer people in the twelfth century.[8]

In popular culture

- Lara Croft: Tomb Raider features several characters visiting Angkor Thom during their trip to Cambodia to recover the first piece of the Triangle of Light.

- In James Rollins' SIGMA Force Book 4: The Judas Strain (2007), the characters' journey to find a cure for a plague, which requires following in the steps of Marco Polo, leads them to the Angkor Thom.

- In Peter Bourne's novel The Golden Pagans (c.1956), the main characters are sent to Arabia during the Crusades, captured, and forced into servitude by the Khmers. The prisoners build a portion of what becomes known as Angkor Thom.

- In Patlabor the Movie 2, the opening scene appears to be based on the Angkor Thom, as said by Hayao Miyazaki in an interview with Animage magazine (October 1993).

- In Civilization IV: Beyond the Sword, Angkor Thom is the third city built in the Khmer Empire, after Yasodharapura and Hariharalaya.

- In Eternal Darkness: Sanity's Requiem, Angkor Thom is the region where a Cambodian temple is located, housing the Ancient Mantorok.

References

Notes

- ↑ http://www.angkor-net.de/

- ↑ http://www.angkor-net.de/

- ↑ Higham, C., 2014, Early Mainland Southeast Asia, Bangkok: River Books Co., Ltd., ISBN 9786167339443

- ↑ Coedès, George (1968). Walter F. Vella, ed. The Indianized States of Southeast Asia. trans.Susan Brown Cowing. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-0368-1.

- 1 2 3 Higham, Charles. 2001. The Civilization of Angkor. Phoenix. ISBN 1-84212-584-2.

- ↑ Chakrabongse, C., 1960, Lords of Life, London: Alvin Redman Limited

- 1 2 3 Glaize, Maurice. 2003. English translation of the 1993 French fourth edition. The Monuments of the Angkor Group. Retrieved 14 July 2005.

- 1 2 Freeman, Michael and Jacques, Claude 1997. Angkor Cities and Temples. Bangkok: River Books.

Bibliography

- Albanese, Marilia (2006). The Treasures of Angkor (Paperback). Vercelli: White Star Publishers. ISBN 88-544-0117-X.

- Freeman, Michael; Jacques, Claude (2003). Ancient Angkor (Paperback). Bangkok: River Books. ISBN 974-8225-27-5.

- Jessup, Helen Ibbitson; Brukoff, Barry (2011). Temples of Cambodia - The Heart of Angkor (Hardback). Bangkok: River Books. ISBN 978-616-7339-10-8.

External links

Media related to Angkor Thom at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Angkor Thom at Wikimedia Commons