Anna May Wong

| Anna May Wong | |

|---|---|

Paramount Pictures publicity photo of Anna May Wong circa 1935 | |

| Born |

Wong Liu Tsong January 3, 1905 Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Died |

February 3, 1961 (aged 56) Santa Monica, California, U.S. |

| Occupation | Actress |

| Years active | 1919–1961 |

| Parent(s) |

Wong Sam Sing Lee Gon Toy |

| Awards |

Hollywood Walk of Fame – Motion Picture 1700 Vine Street |

| Anna May Wong | |||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 黃柳霜 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 黄柳霜 | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

Anna May Wong (January 3, 1905 – February 3, 1961) was an American actress. She is considered to be the first Chinese American movie star,[1] and also the first Asian American actress to gain international recognition.[2] Her long and varied career spanned silent film, sound film, television, stage and radio.

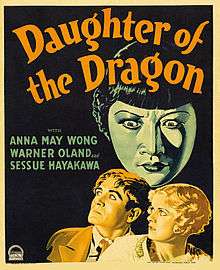

Born in Los Angeles to second-generation Chinese-American parents, Wong became infatuated with the movies and began acting in films at an early age. During the silent film era, she acted in The Toll of the Sea (1922), one of the first movies made in color and Douglas Fairbanks' The Thief of Bagdad (1924). Wong became a fashion icon and had achieved international stardom in 1924. Frustrated by the stereotypical supporting roles she reluctantly played in Hollywood, Wong left for Europe in the late 1920s, where she starred in several notable plays and films, among them Piccadilly (1929). She spent the first half of the 1930s traveling between the United States and Europe for film and stage work. Wong was featured in films of the early sound era, such as Daughter of the Dragon (1931) and Daughter of Shanghai (1937) and with Marlene Dietrich in Josef von Sternberg's Shanghai Express (1932).[3]

In 1935 Wong was dealt the most severe disappointment of her career, when Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer refused to consider her for the leading role of the Chinese character O-Lan in the film version of Pearl S. Buck's The Good Earth, choosing instead the German actress Luise Rainer to play the leading role. Wong spent the next year touring China, visiting her family's ancestral village and studying Chinese culture. In the late 1930s, she starred in several B movies for Paramount Pictures, portraying Chinese Americans in a positive light. She paid less attention to her film career during World War II, when she devoted her time and money to helping the Chinese cause against Japan. Wong returned to the public eye in the 1950s in several television appearances.

In 1951, Ms. Wong made history with her TV show The Gallery of Madame Liu-Tsong, the first ever U.S. television show starring an Asian American series lead.[4]

She had been planning to return to film in Flower Drum Song when she died in 1961, at the age of 56.

For decades after her death, Wong was remembered principally for the stereotypical "Dragon Lady" and demure "Butterfly" roles that she was often given. Her life and career were re-evaluated in the years around the centennial of her birth, in three major literary works and film retrospectives. Interest in her life story continues and another biography, Shining Star: The Anna May Wong Story, was published in 2009.[5]

Biography

Early life

Anna May Wong was born Wong Liu Tsong (meaning "yellow willow frost" respectively, though "yellow" being her family name can be considered functionless here semantically) on January 3, 1905, on Flower Street in Los Angeles, one block north of Chinatown, in an integrated community of Chinese, Irish, German and Japanese residents.[6][7] She was the second of seven children born to Wong Sam Sing, owner of the Sam Kee Laundry in Los Angeles, and his second wife Lee Gon Toy.[8]

Anna May Wong's parents were second-generation Chinese Americans; her maternal and paternal grandparents had resided in the U.S. since at least 1855.[9] Her paternal grandfather, A Wong Wong, was a merchant who owned two stores in Michigan Hills, a gold-mining area in Placer County. He had come from Chang On, a village near Taishan, Guangdong Province, China in 1853.[10] Anna May's father spent his youth traveling between the U.S. and China, where he married his first wife and fathered a son in 1890.[11] He returned to the U.S. in the late 1890s and in 1901, while continuing to support his family in China, he married a second wife, Anna May's mother.[12] Anna May's older sister Lew Ying (Lulu) was born in late 1902,[13] and Anna May was born in 1905, followed by five more children.

In 1910, the family moved to a neighborhood on Figueroa Street where they were the only Chinese on their block, living alongside mostly Mexican and Eastern European families. The two hills separating their new home from Chinatown helped Wong to assimilate into American culture.[14] She attended public school with her older sister at first, but then moved to a Presbyterian Chinese school when the girls became the target of racial taunts from other students. Classes were taught in English, but Wong attended a Chinese language school afternoons and on Saturdays.[15]

About that same time, U.S. motion picture production began to relocate from the east coast to the Los Angeles area. Movies were shot constantly in and around Wong's neighborhood. She began going to Nickelodeon movie theaters and quickly became obsessed with the "flickers", missing school and using lunch money to attend the cinema. Her father was not happy with her interest in films, feeling that it interfered with her studies, but Wong decided to pursue a film career regardless. At the age of nine, she constantly begged filmmakers to give her roles, earning herself the nickname "C.C.C." or "Curious Chinese Child".[16] By the age of 11, Wong had come up with her stage name of Anna May Wong, formed by joining both her English and family names.[17]

Early career

Wong was working at Hollywood's Ville de Paris department store when Metro Pictures needed 300 female extras to appear in Alla Nazimova's film The Red Lantern (1919). Without her father's knowledge, a friend of his with movie connections helped Anna May land an uncredited role as an extra carrying a lantern.[18]

She worked steadily for the next two years as an extra in various movies, including Priscilla Dean and Colleen Moore pictures. While still a student, Wong came down with an illness identified as St. Vitus's Dance which caused her to miss months of school. She was on the verge of emotional collapse when her father took her to a practitioner of traditional Chinese medicine. The treatments proved successful, though Wong later claimed this had more to do with her dislike of the methods.[19] Other Chinese thought such as Confucianism and particularly Taoism and the teachings of Laozi had a strong influence on Wong's personal philosophy throughout her life.[20] The family's religious life also included Christian thought, in the form of Presbyterianism and as an adult she was a Christian Scientist for some time.[21]

Finding it difficult to keep up with both her schoolwork and her passion, she dropped out of Los Angeles High School in 1921 to pursue a full-time acting career.[22][23] Reflecting on her decision, Wong told Motion Picture Magazine in 1931: "I was so young when I began that I knew I still had youth if I failed, so I determined to give myself 10 years to succeed as an actress."[24]

In 1921, Wong received her first screen credit for Bits of Life, the first anthology film, in which she played the wife of Lon Chaney's character, Toy Ling, in a segment entitled "Hop".[25] She later recalled it fondly as the only time she played the role of a mother;[26] her appearance earned her a cover photo in the British magazine Picture Show.

At the age of 17 she played her first leading role, in the early Metro two-color Technicolor movie The Toll of the Sea. Written by Frances Marion, the story was based loosely on Madama Butterfly. Variety magazine singled Wong out for praise, noting her "extraordinarily fine" acting.[27] The New York Times commented, "Miss Wong stirs in the spectator all the sympathy her part calls for and she never repels one by an excess of theatrical 'feeling'. She has a difficult role, a role that is botched nine times out of ten, but hers is the tenth performance. Completely unconscious of the camera, with a fine sense of proportion and remarkable pantomimic accuracy ... She should be seen again and often on the screen."[28]

Despite such reviews, Hollywood proved reluctant to create starring roles for Wong; her ethnicity prevented U.S. filmmakers from seeing her as a leading lady. David Schwartz, the chief curator of the Museum of the Moving Image, notes, "She built up a level of stardom in Hollywood, but Hollywood didn't know what to do with her."[29] She spent the next few years in supporting roles providing "exotic atmosphere",[30] for instance playing a concubine in Tod Browning's Drifting (1923).[24] Film producers capitalized on Wong's growing fame but they relegated her to supporting roles.[31] Still optimistic about a film career, in 1923 Wong said: "Pictures are fine and I'm getting along all right, but it's not so bad to have the laundry back of you, so you can wait and take good parts and be independent when you're climbing."[17]

Stardom

At the age of 19, Anna May Wong was cast in a supporting role as a scheming Mongol slave in the Douglas Fairbanks picture The Thief of Bagdad (1924). Playing a stereotypical "Dragon Lady" role, her brief appearances on-screen caught the attention of audiences and critics alike.[32] The film grossed more than $2 million and helped introduce Wong to the public. Around this time, Wong had an affair with director Tod Browning. It was a romance largely known of at the time: it was an interracial relationship and Wong was underage.[33]

After this second prominent role, Wong moved out of the family home into her own apartment. Conscious that Americans viewed her as "foreign born" even though she was born and raised in California, Wong began cultivating a flapper image.[34] In March 1924, planning to make films about Chinese myths, she signed a deal creating Anna May Wong Productions; when her business partner was found to be engaging in dishonest practices, Wong brought a lawsuit against him and the company was dissolved.[35]

It soon became evident that Wong's career would continue to be limited by American anti-miscegenation laws, which prevented her from sharing an on-screen kiss with any person of another race, even if the character was Asian, but being portrayed by a white actor.[36] The only leading Asian man in U.S. films in the silent era was Sessue Hayakawa. Unless Asian leading men could be found, Wong could not be a leading lady.[37]

Wong continued to be offered exotic supporting roles, playing indigenous native girls in two 1924 films. Filmed on location in the Territory of Alaska she portrayed an Eskimo in The Alaskan. She returned to Los Angeles to perform the part of Princess Tiger Lily in Peter Pan. Both films were shot by cinematographer James Wong Howe but Peter Pan was more successful; the hit of the Christmas season.[38][39] The next year, Wong was singled out for critical praise in a manipulative Oriental vamp role in the film Forty Winks.[40] Despite such favorable reviews, she became increasingly disappointed with her casting and began to seek other roads to success. In early 1925 she joined a group of serial stars on a tour of the vaudeville circuits; when the tour proved to be a failure, Wong and the rest of the group returned to Hollywood.[41]

In 1926, Wong put the first rivet into the structure of Grauman's Chinese Theatre when she joined Norma Talmadge for its groundbreaking ceremony, although she was not invited to leave her hand- and foot-prints in cement.[42][43]

In the same year Wong starred in The Silk Bouquet. Re-titled The Dragon Horse in 1927, the film was one of the first U.S. films to be produced with Chinese backing, provided by San Francisco's Chinese Six Companies. The story was set in China during the Ming Dynasty and featured Asian actors playing the Asian roles.[44]

Wong continued to be assigned supporting roles. Hollywood's Asian female characters tended toward two stereotypical poles: the naïve and self-sacrificing "Butterfly" and the sly and deceitful "Dragon Lady". In Old San Francisco (1927), directed by Alan Crosland for Warner Brothers, Wong played a "Dragon Lady", a gangster's daughter.[45] In Mr. Wu (1927) she played a supporting role as increasing censorship against mixed race onscreen couples cost her the lead. In The Crimson City, released the following year, this happened again.[46]

Move to Europe

Tired of being both typecast and being passed over for lead Asian character roles in favor of non-Asian actresses, Wong left Hollywood in 1928 for Europe.[47] Interviewed by Doris Mackie for Film Weekly in 1933, Wong complained about her Hollywood roles: "I was so tired of the parts I had to play."[48][49] She commented: "There seems little for me in Hollywood, because, rather than real Chinese, producers prefer Hungarians, Mexicans, American Indians for Chinese roles."[50]

In Europe, Wong became a sensation, starring in notable films such as Schmutziges Geld (aka Song and Show Life, 1928) and Großstadtschmetterling (Pavement Butterfly). Of the German critics' response to Song, The New York Times reported that Wong was "acclaimed not only as an actress of transcendent talent but as a great beauty". The article noted that Germans passed over Wong's American background: "Berlin critics, who were unanimous in praise of both the star and the production, neglect to mention that Anna May is of American birth. They mention only her Chinese origins."[51] In Vienna, she played the title role in the operetta Tschun Tschi in fluent German.[49] An Austrian critic wrote, "Fräulein Wong had the audience perfectly in her power and the unobtrusive tragedy of her acting was deeply moving, carrying off the difficult German-speaking part very successfully."[52]

While in Germany, Wong became an inseparable friend of the director Leni Riefenstahl. Her close friendships with several women throughout her life, including Marlene Dietrich and Cecil Cunningham, led to rumors of lesbianism which damaged her public reputation.[53] These rumors, in particular of her supposed relationship with Dietrich, embarrassed Wong's family who in any case had long been opposed to her acting career, at that time not considered to be an entirely respectable profession.[54]

London producer Basil Dean bought the play A Circle of Chalk for Wong to appear in with the young Laurence Olivier, her first stage performance in the UK.[49] Criticism of her California accent, described by one critic as a "Yankee squeak", led to Wong seeking vocal tutoring at Cambridge University, where she acquired a British accent.[55] Composer Constant Lambert, infatuated with the actress after having seen her in films, attended the play on its opening night and subsequently composed Eight Poems of Li Po, dedicated to her.[56]

Wong made her last silent film, Piccadilly, in 1929, the first of five English films in which she had a starring role. The film caused a sensation in the UK.[57] Gilda Gray was the top-billed actress, but Variety commented that Wong "outshines the star" and that "from the moment Miss Wong dances in the kitchen's rear, she steals 'Piccadilly' from Miss Gray."[58] Though the film presented Wong in her most sensual role in a British film, once again she was not permitted to kiss her Caucasian love interest and a controversial planned scene involving a kiss was cut before the film was released.[59] Forgotten for decades after its release, Piccadilly was later restored by the British Film Institute.[60] Time magazine's Richard Corliss calls Piccadilly Wong's best film,[61] and The Guardian reports that the rediscovery of this film and Wong's performance in it has been responsible for a restoration of the actress' reputation.[42]

While in London, Wong was romantically linked with writer and broadcasting executive Eric Maschwitz, who wrote the lyrics to "These Foolish Things (Remind Me Of You)" as an evocation of his longing for her after they parted.[42][62] Wong's first talkie was The Flame of Love (1930), which she recorded in French, English and German. Though Wong's performance – particularly her handling of the three languages – was lauded, all three versions of the film received negative reviews.[63]

Return to Hollywood

During the 1930s, American studios were looking for fresh European talent. Ironically, Wong caught their eye and she was offered a contract with Paramount Studios in 1930. Enticed by the promise of lead roles and top billing, she returned to the United States. The prestige and training she had gained during her years in Europe led to a starring role on Broadway in On the Spot,[64] a drama that ran for 167 performances and which she would later film as Dangerous to Know.[65] When the play's director wanted Wong to use stereotypical Japanese mannerisms, derived from Madame Butterfly, in her performance of a Chinese character, Wong refused. She instead used her knowledge of Chinese style and gestures to imbue the character with a greater degree of authenticity.[66] Following her return to Hollywood in 1930, Wong repeatedly turned to the stage and cabaret for a creative outlet.

In November 1930, Anna May's mother was run over and killed by an automobile in front of the Figueroa Street house.[67] The family remained at the house until 1934, when Wong's father returned to his hometown in China with Anna May's younger brothers and sister.[68] Anna May had been paying for the education of her younger siblings, who put their education to work after they relocated to China.[69] Before the family left, Wong's father wrote a brief article for Xinning, a magazine for overseas Taishanese, in which he expressed his pride in his famous daughter.[70]

With the promise of appearing in a Josef von Sternberg film, Wong accepted another stereotypical role – the title character of Fu Manchu's vengeful daughter in Daughter of the Dragon (1931).[71] This was the last stereotypically "evil Chinese" role Wong played,[72] and also her one starring appearance alongside the only other well-known Asian actor of the era, Sessue Hayakawa. Though she was given the starring role, this status was not reflected in her paycheck: she was paid $6,000, while Hayakawa received $10,000 and Warner Oland, who is only in the film for 23 minutes, was paid $12,000.[73]

Wong began using her newfound celebrity to make political statements: late in 1931, for example, she wrote a harsh criticism of the Mukden Incident and Japan's subsequent invasion of Manchuria.[74][75] She also became more outspoken in her advocacy for Chinese American causes and for better film roles. In a 1933 interview for Film Weekly entitled "I Protest", Wong criticized the negative stereotyping in Daughter of the Dragon, saying, "Why is it that the screen Chinese is always the villain? And so crude a villain – murderous, treacherous, a snake in the grass! We are not like that. How could we be, with a civilization that is so many times older than the West?"[48][76]

Wong appeared alongside Marlene Dietrich as a self-sacrificing courtesan in Sternberg's Shanghai Express.[71] Her sexually charged scenes with Dietrich have been noted by many commentators and fed rumors about the relationship between the two stars.[77] Though contemporary reviews focused on Dietrich's acting and Sternberg's direction, film historians today judge that Wong's performance upstaged that of Dietrich.[71][78]

The Chinese press had long given Wong's career very mixed reviews, and were less than favorable to her performance in Shanghai Express. A Chinese newspaper ran the headline: "Paramount Utilizes Anna May Wong to Produce Picture to Disgrace China" and continued, "Although she is deficient in artistic portrayal, she has done more than enough to disgrace the Chinese race."[79] Critics in China believed that Wong's on-screen sexuality spread negative stereotypes of Chinese women.[80] The most virulent criticism came from the Nationalist government, but China's intellectuals and liberals were not always so opposed to Wong, as demonstrated when Peking University awarded the actress an honorary doctorate in 1932. Contemporary sources reported that this was probably the only time that an actor had been so honored.[81]

In both America and Europe, Wong had been seen as a fashion icon for over a decade. In 1934, the Mayfair Mannequin Society of New York voted her "The World's best-dressed woman" and in 1938 Look magazine named her "The World's most beautiful Chinese girl".[82]

Atlantic crossings

After her success in Europe and prominent role in Shanghai Express, Wong's Hollywood career returned to its old pattern. Because of the Hays Code's anti-miscegenation rules, she was passed over for the leading female role in The Son-Daughter in favor of Helen Hayes. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer deemed her "too Chinese to play a Chinese" in the film,[83] and the Hays Office would not have allowed her to perform romantic scenes since the film's male lead, Ramón Novarro, was not Asian.[71] Wong was scheduled to play the role of a mistress to a corrupt Chinese general in Frank Capra's The Bitter Tea of General Yen (1933), but the role went instead to Toshia Mori.[84]

Again disappointed with Hollywood, Wong returned to Britain, where she stayed for nearly three years. In addition to appearing in four films she toured Scotland and Ireland as part of a vaudeville show. She also appeared in the King George Silver Jubilee program in 1935.[85] Her film Java Head (1934), though generally considered a minor effort, was the only film in which Wong kissed the lead male character, her white husband in the film. Wong's biographer, Graham Russell Hodges, commented that this may be why the film remained one of Wong's personal favorites.[86] While in London, Wong met Mei Lanfang, one of the most famous stars of the Beijing Opera. She had long been interested in Chinese opera and Mei offered to instruct Wong if she ever visited China.[87]

In the 1930s, the popularity of Pearl Buck's novels, especially The Good Earth, as well as growing American sympathy for China in its struggles with Japanese Imperialism, opened up opportunities for more positive Chinese roles in U.S. films.[88] Wong returned to the U.S. in June 1935 with the goal of obtaining the role of O-lan, the lead female character in MGM's film version of The Good Earth. Since its publication in 1931, Wong had made known her desire to play O-lan in a film version of the book;[89] and as early as 1933, Los Angeles newspapers were touting Wong as the best choice for the part.[90] Nevertheless, the studio apparently never seriously considered Wong for the role because Paul Muni, an actor of European descent, was to play O-lan's husband, Wang Lung. The Chinese government also advised the studio against casting Wong in the role. The Chinese advisor to MGM commented: "whenever she appears in a movie, the newspapers print her picture with the caption 'Anna May again loses face for China' ".[91]

According to Wong, she was instead offered the part of Lotus, a deceitful song girl who helps to destroy the family and seduces the family's oldest son.[92] Wong refused the role, telling MGM head of production Irving Thalberg, "If you let me play O-lan, I will be very glad. But you're asking me – with Chinese blood – to do the only unsympathetic role in the picture featuring an all-American cast portraying Chinese characters."[90] The role Wong hoped for went to Luise Rainer, who won the Best Actress Oscar for her performance. Wong's sister, Mary Liu Heung Wong, appeared in the film in the role of the Little Bride.[93] MGM's refusal to consider Wong for this most high-profile of Chinese characters in U.S. film is remembered today as "one of the most notorious cases of casting discrimination in the 1930s".[94]

Tour of China

After the major disappointment of losing the role in The Good Earth, Wong announced plans for a year-long tour of China, to visit her father and his family in Taishan.[68][95] Wong's father had returned to his hometown in China with her younger brothers and sister in 1934. Aside from Mei Lanfang's offer to teach her, she wanted to learn more about the Chinese theater and through English translations to better perform some Chinese plays before international audiences.[69][96] She told the San Francisco Chronicle on her departure, "... for a year, I shall study the land of my fathers. Perhaps upon my arrival, I shall feel like an outsider. Perhaps instead, I shall find my past life assuming a dreamlike quality of unreality."[68]

Embarking in January 1936, she chronicled her experiences in a series of articles printed in U.S. newspapers such as the New York Herald Tribune,[85] the Los Angeles Examiner, the Los Angeles Times, and Photoplay.[97] In a stopover in Tokyo on the way to Shanghai, local reporters, ever curious about her romantic life, asked if she had marriage plans, to which Wong replied, "No, I am wedded to my art." The following day, however, Japanese newspapers reported that Wong was married to a wealthy Cantonese man named Art.[85][98]

During her travels in China, Wong continued to be strongly criticized by the Nationalist government and the film community.[99] She had difficulty communicating in many areas of China because she was raised with the Taishan dialect rather than Mandarin. She later commented that some of the varieties of Chinese sounded "as strange to me as Gaelic. I thus had the strange experience of talking to my own people through an interpreter."[100]

The toll of international celebrity on Wong's personal life manifested itself in bouts of depression and sudden anger, as well as excessive smoking and drinking.[101] Feeling irritable when she disembarked in Hong Kong, Wong was uncharacteristically rude to the awaiting crowd, which then quickly turned hostile. One person shouted: "Down with Huang Liu Tsong – the stooge that disgraces China. Don't let her go ashore." Wong began crying and a stampede ensued.[102] After she left for a short trip to the Philippines, the situation cooled and Wong joined her family in Hong Kong. With her father and her siblings, Wong visited his family and his first wife at the family's ancestral home near Taishan.[95][103] Conflicting reports claim that she was either warmly welcomed or met with hostility by the villagers. She spent over 10 days in the family's village and some time in neighboring villages before continuing her tour of China.[104] After returning to Hollywood, Wong reflected on her year in China and her career in Hollywood: "I am convinced that I could never play in the Chinese Theatre. I have no feeling for it. It's a pretty sad situation to be rejected by Chinese because I'm 'too American' and by American producers because they prefer other races to act Chinese parts."[95] Wong's father returned to Los Angeles in 1938.[105]

Late 1930s

To complete her contract with Paramount Pictures, Wong made a string of B movies in the late 1930s. Often dismissed by critics, the films gave Wong non-stereotypical roles which were publicized in the Chinese-American press for their positive images. These smaller-budgeted films could be bolder than the higher-profile releases and Wong used this to her advantage to portray successful, professional, Chinese-American characters. Competent and proud of their Chinese heritage, these roles worked against the prevailing U.S. film portrayals of Chinese Americans.[106] In contrast to the usual official Chinese condemnation of Wong's film roles, the Chinese consul to Los Angeles gave his approval to the final scripts of two of these films, Daughter of Shanghai (1937) and King of Chinatown (1939).[107]

In Daughter of Shanghai, Wong played the Asian-American female lead in a role that was rewritten for her as the heroine of the story, actively setting the plot into motion rather than the more passive character originally planned.[109] The script was so carefully tailored for Wong that at one point it was titled, Anna May Wong Story.[96] Of this film, Wong told Hollywood Magazine, "I like my part in this picture better than any I've had before ... because this picture gives Chinese a break – we have sympathetic parts for a change! To me that means a great deal."[110] The New York Times gave the film a generally positive review, commenting of its B-movie origins, "An unusually competent cast saves the film from the worst consequences of certain inevitable banalities. [The cast] ... combine with effective sets to reduce the natural odds against any pictures in the Daughter of Shanghai tradition."[111] In October 1937, the press carried rumors that Wong had plans to marry her male co-star in this film, childhood friend and Korean-American actor Philip Ahn.[95] Wong replied, "It would be like marrying my brother."[112]

Bosley Crowther was not so kind to Dangerous to Know (1938), which he called a "second-rate melodrama, hardly worthy of the talents of its generally capable cast".[113] In King of Chinatown Wong played a surgeon who sacrifices a high-paying promotion in order to devote her energies to helping the Chinese fight the Japanese invasion.[114] The New York Times' Frank Nugent gave the film a negative review. Though he commented positively on its advocacy of the Chinese in their fight against Japan, he wrote, "... Paramount should have spared us and its cast ... the necessity of being bothered with such folderol".[115]

Paramount also employed Wong as a tutor to other actors, such as Dorothy Lamour in her role as a Eurasian in Disputed Passage.[95] Wong performed on radio several times, including a 1939 role as "Peony" in Pearl Buck's The Patriot on Orson Welles' The Campbell Playhouse.[116] Wong's cabaret act, which included songs in Cantonese, French, English, German, Danish, Swedish, and other languages, took her from the U.S. to Europe and Australia through the 1930s and 1940s.[117]

In 1938, having auctioned off her movie costumes and donated the money to Chinese aid, the Chinese Benevolent Association of California honored Wong for her work in support of Chinese refugees.[118] The proceeds from the preface that she wrote in 1942 to a cookbook titled New Chinese Recipes, one of the first Chinese cookbooks, were also dedicated to United China Relief.[119] Between 1939 and 1942, she made few films, instead engaging in events and appearances in support of the Chinese struggle against Japan.

Being sick of the negative typecasting that had enveloped her throughout her American career, Anna May Wong visited Australia for over 3 months in 1939. There she was the star attraction in a vaudeville show titled 'Highlights from Hollywood' at the Tivoli Theatre in Melbourne.[120][121]

Later years

Wong starred in Lady from Chungking (1942) and Bombs over Burma (1942), both anti-Japanese propaganda made by the poverty row studio Producers Releasing Corporation. She donated her salary for both films to United China Relief.[122] The Lady from Chungking differed from the usual Hollywood war film in that the Chinese were portrayed as heroes rather than as victims rescued by Americans. Even after American characters are captured by the Japanese, the primary goal of the heroes is not to free the Americans, but to prevent the Japanese from entering the city of Chongqing (Chungking). Also, in an interesting twist, the Chinese characters are portrayed by Chinese-American actors, while the Japanese villains – normally played by Chinese-American actors – are acted by European Americans. The film ends with Wong making a speech for the birth of a "new China".[122] The Hollywood Reporter and Variety both gave Wong's performance in The Lady from Chungking positive reviews, but commented negatively on the film's plot.

Later in life, Wong invested in real estate and owned a number of properties in Hollywood.[123] She converted her home on San Vicente Boulevard in Santa Monica into four apartments which she called "Moongate Apartments".[124] She served as the apartment house manager from the late 1940s until 1956, when she moved in with her brother Richard on 21st Place in Santa Monica.[125]

In 1949, Wong's father died in Los Angeles at the age of 91.[105] After a six-year absence, Wong returned to film the same year with a small role in a B movie called Impact.[126] From August 27 to November 21, 1951, Wong starred in a detective series that was written specifically for her, the DuMont Television Network series The Gallery of Madame Liu-Tsong,[126] in which she played the title role which used her birth name.[117] Wong's character was a dealer in Chinese art whose career involved her in detective work and international intrigue.[127] The ten half-hour episodes aired during prime time, from 9:00 to 9:30 p.m.[128] Although there were plans for a second season, DuMont canceled the show in 1952. No copies of the show or its scripts are known to exist.[129] After the completion of the series, Wong's health began to deteriorate. In late 1953 she suffered an internal hemorrhage, which her brother attributed to the onset of menopause, her continued heavy drinking, and financial worries.[130]

In 1956, Wong hosted one of the first U.S. documentaries on China narrated entirely by a Chinese American. Broadcast on the ABC travel series Bold Journey, the program consisted of film footage from her 1936 trip to China.[131] Wong also did guest spots on television series such as Adventures in Paradise, The Barbara Stanwyck Show, and The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp.[132]

For her contribution to the film industry, Anna May Wong received a star at 1708 Vine Street on the inauguration of the Hollywood Walk of Fame in 1960.[133] She is also depicted larger-than-life as one of the four supporting pillars of the "Gateway to Hollywood" sculpture located on the southeast corner of Hollywood Boulevard and La Brea Avenue, with the actresses Dolores del Río (Hispanic American), Dorothy Dandridge (African American) and Mae West.[134]

In 1960, Wong returned to film in Portrait in Black, starring Lana Turner. She still found herself stereotyped, with one press release explaining her long absence from films with a supposed proverb, which was claimed to have been passed down to Wong by her father: "Don't be photographed too much or you'll lose your soul",[42] a quote that would be inserted into many of her obituaries.[117]

Death

She was scheduled to play the role of Madame Liang in the film production of Rodgers and Hammerstein's Flower Drum Song, but was unable to take the role due to failing health.[135] On February 3, 1961, at the age of 56, Wong died of a heart attack as she slept at home in Santa Monica, two days after her final screen performance on the television show The Barbara Stanwyck Show. Her cremated remains were interred in her mother's grave at Rosedale Cemetery in Los Angeles. The headstone is marked with her mother's Anglicized name on top, and the Chinese names of Anna May (on the right) and her sister Mary (on the left) along the sides. She was survived by her 3 daughters: Shila (May 31, 1927 – August 9, 1963); Wanda (February 17, 1929 – March 26, 1996); and Leah (December 2, 1931 – April 13, 2001).

Legacy

Wong's image and career have left a legacy. Through her films, public appearances and prominent magazine features, she helped to humanize Asian Americans to white audiences during a period of overt racism and discrimination. Asian Americans, especially the Chinese, had been viewed as perpetually foreign in U.S. society but Wong's films and public image established her as an Asian-American citizen at a time when laws discriminated against Asian immigration and citizenship. Wong's hybrid image dispelled contemporary notions that the East and West were inherently different.[136]

Among Wong's films, only Shanghai Express retained critical attention in the U.S. in the decades after her death. In Europe and especially England, her films appeared occasionally at festivals. Wong remained popular with the gay community who often claimed her as one of their own and for whom her marginalization by the mainstream became a symbol.[137] Although the Chinese Nationalist criticism of her portrayals of the "Dragon Lady" and "Butterfly" stereotypes lingered, Wong herself was forgotten in China.[138] Nevertheless, the importance of Wong's legacy within the Asian-American film community can be seen in the Anna May Wong Award of Excellence, which is given yearly at the Asian-American Arts Awards;[139] the annual award given out by the Asian Fashion Designers was also named after Wong in 1973.[137]

For decades following her death, Wong's image remained as a symbol in literature as well as in film. In the 1971 poem "The Death of Anna May Wong", Jessica Hagedorn saw Wong's career as one of "tragic glamour" and portrayed the actress as a "fragile maternal presence, an Asian-American woman who managed to 'birth' however ambivalently, Asian-American screen women in the jazz age".[140] Wong's character in Shanghai Express was the subject of John Yau's 1989 poem "No One Ever Tried to Kiss Anna May Wong", which interprets the actress' career as a series of tragic romances.[141] In David Cronenberg's 1993 film version of David Henry Hwang's 1986 play, M. Butterfly, Wong's image was used briefly as a symbol of a "tragic diva".[142] Her life was the subject of China Doll, The Imagined Life of an American Actress, an award-winning[143] fictional play written by Elizabeth Wong in 1995.[144]

As the centennial of Wong's birth approached, a re-examination of her life and career took shape; three major works on the actress appeared and comprehensive retrospectives of her films were held at both the Museum of Modern Art and the American Museum of the Moving Image in New York City.[60][145] Anthony Chan's 2003 biography, Perpetually Cool: The Many Lives of Anna May Wong (1905–1961), was the first major work on Wong and was written, Chan says, "from a uniquely Asian-American perspective and sensibility".[146] In 2004, Philip Leibfried and Chei Mi Lane's exhaustive examination of Wong's career, Anna May Wong: A Complete Guide to Her Film, Stage, Radio and Television Work was published, as well as a second full-length biography, Anna May Wong: From Laundryman's Daughter to Hollywood Legend by Graham Russell Hodges. Though Anna May Wong's life, career and legacy reflect many complex issues which remain decades after her death, Anthony Chan points out that her place in Asian-American cinematic history, as its first female star, is permanent.[147]

Partial filmography

- The Red Lantern (1919) debut – uncredited

- Bits of Life (1921)

- The Toll of the Sea (1922) as Lotus Flower

- The Thief of Bagdad (1924) as a Mongol Slave

- A Trip to Chinatown (1926) as Ohati

- Old San Francisco (1927)

- Piccadilly (1929) as Shosho

- Elstree Calling (1930) as Herself

- The Flame of Love (1930) as Hai Tang

- The Road to Dishonour (1930) as Hai Tang

- Hai-Tang (1930) as Hai Tang

- Daughter of the Dragon (1931) as Princess Ling Moy

- Shanghai Express (1932) as Hui Fei

- A Study in Scarlet (1933)

- Limehouse Blues (1934) as Tu Tuan

- Dangerous to Know (1938) as Lan Ying

- Island of Lost Men (1939) as Kim Ling

- King of Chinatown (1939) as Dr. Mary Ling

- Bombs Over Burma (1942) as Lin Ying

- Lady from Chungking (1942) as Kwan Mei

- Impact (1949) as Su Lin

- Portrait in Black (1960) as Tawny

See also

- Portrayal of East Asians in Hollywood

- Racism in Film of the United States

- Stereotypes of East and Southeast Asians in American media

References

Notes

- ↑ Chan 2003, p. xi.

- ↑ Gan 1995, p. 83.

- ↑ Zia 1995, p. 415.

- ↑ "Film reveals real-life struggles of an onscreen 'Dragon Lady'." (2008).

- ↑ Maughan, Shannon. "Spring 2009 Sneak Previews: Shining Star by Paula Yoo, illus. by Lin Wang, a biography of Chinese-American actress Anna May Wong." Publishers Weekly Volume 255, Issue 29, July 2008, p. 125. Retrieved: August 1, 2008.

- ↑ Hodges 2004, pp. 2, 5.

- ↑ Corliss January 29, 2005, p. 2.

- ↑ Finch and Rosenkrantz 1979, p. 231.

- ↑ Hodges 2004, p. 1.

- ↑ Hodges 2004, p. 6.

- ↑ Chan 2003, p. 13.

- ↑ Hodges 2004, pp. 1, 7–8, 10.

- ↑ Hodges 2004, p. 2.

- ↑ Hodges 2004, p. 5.

- ↑ Hodges 2004, pp. 13–15.

- ↑ Hodges 2004, p. 21.

- 1 2 Wollstein 1999, p. 248.

- ↑ Chan 2003, p. 31.

- ↑ Hodges 2004, pp. 26–27.

- ↑ Chan 2003, pp. 145–146.

- ↑ Hodges 2004, p. 225.

- ↑ Lim 2005, p. 51.

- ↑ Hodges 2004, p. 41.

- 1 2 Wollstein 1999, p. 249.

- ↑ Gan 1995, p. 84.

- ↑ Hodges 2004, p. 35.

- ↑ The Toll of the Sea (film review) December 1, 1922.

- ↑ The Toll of the Sea (film review) November 27, 1922.

- ↑ Anderson, Melissa. "The Wong Show." Time Out: New York, Issue 544: March 2–8, 2006, TimeOut. Retrieved: March 24, 2008.

- ↑ Parish 1976, pp. 532–533.

- ↑ Hodges 2004, p. 58.

- ↑ Hodges 2004, p. 49.

- ↑ Hollywood Horror: from Gothic to Cosmic, Mark A. Vierra c. 2003

- ↑ Chan 2003, pp. 37, 139.

- ↑ Chan 2003, pp. 37–38.

- ↑ Leong 2005, pp. 181–182.

- ↑ Hodges 2004, p. 64.

- ↑ Hodges 2004, pp. 45–46.

- ↑ Bergfelder 2004, pp. 61–62.

- ↑ Forty Winks (film review), February 3, 1925.

- ↑ Wollstein 1999, p. 250.

- 1 2 3 4 Sweet 2008.

- ↑ Hodges 2004, p. 66.

- ↑ Chan 2003, p. 185.

- ↑ Liu 2000, p. 24.

- ↑ Rohter, Larry. " The Crimson City (1928)." The New York Times, September 2, 2010. Retrieved: September 2, 2010.

- ↑ Chan 2003, p. 42.

- 1 2 Leong 2005, pp. 83, 187.

- 1 2 3 Wollstein 1999, p. 252.

- ↑ Parish 1976, p. 533.

- ↑ Song (film review). August 22, 1928.

- ↑ Parish 1976, p. 534.

- ↑ Wollstein 1999, pp. 252, 253, 256.

- ↑ Hodges 2004, p. 87.

- ↑ Hodges 2004, p. 97.

- ↑ Motion 1986, p. 161.

- ↑ Hodges 2004, p. 92.

- ↑ Piccadilly (film review) July 24, 1929.

- ↑ Chan 2003, pp. xiii, 213, 215, 219.

- 1 2 Hsu 2004.

- ↑ Corliss January 29, 2005, pp. 1, 3.

- ↑ Hodges 2004, p. 178.

- ↑ Chan 2003, pp. 51–53.

- ↑ Lim 2005, p. 56.

- ↑ Hodges 2004, p. 187.

- ↑ Lim 2005, p. 57.

- ↑ Hodges 2004, p. 112.

- 1 2 3 Chan 2003, p. 90.

- 1 2 Hodges 2004, p. 155.

- ↑ Hodges 2004, p. 148.

- 1 2 3 4 Wollstein 1999, p. 253.

- ↑ Lim 2005, p. 59.

- ↑ Corliss February 3, 2005, p. 4.

- ↑ Hodges 2004, p. 118.

- ↑ Chan 2003, pp. 95–96.

- ↑ Lim 2005, p. 58.

- ↑ Chan 2003, p. 232.

- ↑ Lim 2005, p. 60.

- ↑ Leong 2005, p. 74.

- ↑ Leong 2005, p. 75.

- ↑ Mein Film 1932, p. 333. Cited in Hodges 2004, p. 125.

- ↑ Chan 2003, p. 33.

- ↑ Hodges 2004, p. 128.

- ↑ Hodges 2004, pp. 127–128.

- 1 2 3 Gan 1995, p. 89.

- ↑ Hodges 2004, pp. 144, 217.

- ↑ Hodges 2004, pp. 150, 155.

- ↑ Leong 2005, pp. 75, 94.

- ↑ Hodges 2004, pp. 150–151.

- 1 2 Hodges 2004, p. 152.

- ↑ Hodges 2004, p. 151.

- ↑ Leong 2005, p. 76.

- ↑ Chan 2003, p. 261.

- ↑ Berry 2000, p. 111.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Parish 1976, p. 536.

- 1 2 Liu 2000, p. 29.

- ↑ Liu 2000, pp. 28–29.

- ↑ Chan 2003, p. 97.

- ↑ Hodges 2004, pp. 159–160.

- ↑ Chan 2003, p. 99.

- ↑ Hodges 2004, p. 134.

- ↑ Hodges 2004, pp. 165–167.

- ↑ Chan 2003, pp. 122–123.

- ↑ Hodges 2004, p. 168.

- 1 2 Chan 2003, p. 280.

- ↑ Lim 2005, pp. 47, 63, 67.

- ↑ Leong 2005, p. 94.

- ↑ Hodges 2004, p. 180.

- ↑ Lim 2005, p. 66.

- ↑ Leung, Louise. "East Meets West", Hollywood Magazine, June 1938, pp. 40, 55. Quoted in Leong 2005, p. 94.

- ↑ Crisler 1937.

- ↑ Wollstein 1999, p. 256.

- ↑ Crowther 1938.

- ↑ Lim 2005, p. 47.

- ↑ Nugent 1939.

- ↑ Hodges 2004, p. 191.

- 1 2 3 Corliss January 29, 2005, p. 1.

- ↑ Leong 2005, p. 95.

- ↑ Hodges 2004, p. 203.

- ↑ "Oriental stardust: Anna May Wong in White Australia."

- ↑ "Anna May Wong's Lucky Shoes:1939 Australia through the eyes of an Art Deco Diva."

- 1 2 Leong 2005, p. 101.

- ↑ Finch and Rosenkrantz 1979, p. 156.

- ↑ Parish 1976, p. 538.

- ↑ Wollstein 1999, pp. 257–258.

- 1 2 Chan 2003, p. 78.

- ↑ Camhi 2004.

- ↑ Chan 2003, p. 80.

- ↑ Hodges 2004, pp. 216–217.

- ↑ Hodges 2004, pp. 217–218.

- ↑ Chan 2003, p. 124.

- ↑ Chan 2003, pp. 81, 268.

- ↑ Chung 2006, p. 26.

- ↑ Negra 2001, p. 1.

- ↑ Chan 2003, pp. 80–81.

- ↑ Lim 2005, pp. 49–51.

- 1 2 Hodges 2004, p. 232.

- ↑ Hodges 2004, pp. 231–232.

- ↑ Chan 2003, p. 276.

- ↑ Liu 2000, p. 35.

- ↑ Liu 2000, pp. 31–33.

- ↑ Liu 2000, pp. 34–35.

- ↑ "ACTF: The David Mark Cohen National Playwriting Award." Kennedy Center. Retrieved: March 8, 2010.

- ↑ "UCSB Special Collections: California Ethnic and Multicultural Archives." Library.ucsb.edu. Retrieved: March 8, 2010.

- ↑ Performing Race on Screen.

- ↑ Chan 2003, p. xvii.

- ↑ Chan 2003, p. 275.

Bibliography of cited sources

- Bergfelder, Tim. "Negotiating Exoticism: Hollywood, Film Europe and the cultural reception of Anna May Wong" in Stars: The Film Reader (Lucy Fischer and Marcia Landy, editors.) Psychology Press, 2004. ISBN 0-415-27892-9

- Berry, Sarah. Screen Style: Fashion and Femininity in 1930s Hollywood. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000. ISBN 0-8166-3312-6.

- Camhi, Leslie. "Film: A Dragon Lady and a Quiet Cultural Warrior". The New York Times, January 11, 2004.

- Chan, Anthony B. Perpetually Cool: The Many Lives of Anna May Wong (1905–1961). Lanham, Maryland: The Scarecrow Press, 2003. ISBN 0-8108-4789-2.

- Chung, Hye-seung. Hollywood Asian: Philip Ahn and the Politics of Cross-ethnic Performance. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2006. ISBN 1-59213-516-1.

- Corliss, Richard. "Anna May Wong Did It Right." Time, January 29, 2005. Retrieved: March 20, 2008.

- Corliss, Richard. "That Old Feeling: Anna May Win." Time, February 3, 2005. Retrieved: March 24, 2008.

- Crisler, B.R. Daughter of Shanghai (film review). The New York Times, December 24, 1937.

- Crowther, Bosley. Dangerous to Know (film review). The New York Times, March 11, 1938.

- "Film reveals real-life struggles of an onscreen 'Dragon Lady'." UCLA Today Online, January 3, 2008. Retrieved: May 27, 2008.

- Finch, Christopher and Linda Rosenkrantz. Gone Hollywood: The Movie Colony in the Golden Age. Garden City, New York: Doubleday, 1979. ISBN 978-0-385-12808-7.

- Forty Winks (film review). The New York Times, February 3, 1925.

- Gan, Geraldine. "Anna May Wong." Lives of Notable Asian Americans: Arts, Entertainment, Sports. New York: Chelsea House, 1995, pp. 83–91. ISBN 978-0-7910-2188-0.

- Hodges, Graham Russell. Anna May Wong: From Laundryman's Daughter to Hollywood Legend. Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004. ISBN 0-312-29319-4. 2nd Edition, Hong Kong University Press, 2012.

- Hsu, Shirley. ""Nobody's Lotus Flower: Rediscovering Anna May Wong" Film Retrospective." Asia Pacific Arts Online Magazine. UCLA Asia Institute. January 23, 2004. Retrieved: May 12, 2008.

- Leibfried, Philip and Chei Mi Lane. Anna May Wong: A Complete Guide to her Film, Stage, Radio and Television Work. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2004. ISBN 0-7864-1633-5.

- Leong, Karen J. The China Mystique: Pearl S. Buck, Anna May Wong, Mayling Soong, and the Transformation of American Orientalism. Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 2005. ISBN 0-520-24422-2.

- Lim, Shirley Jennifer. "I Protest: Anna May Wong and the Performance of Modernity, (Chapter title)"A Feeling of Belonging: Asian American Women's Public Culture, 1930–1960. New York: New York University Press, 2005, pp. 104–175. ISBN 0-8147-5193-8.

- Liu, Cynthia W. "When Dragon Ladies Die, Do They Come Back as Butterflies? Re-imagining Anna May Wong." Countervisions: Asian American Film Criticism. Hamamoto, Darrel and Sandra Liu, (editors). Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2000, pp. 23–39. ISBN 1-56639-776-6.

- Motion, Andrew. The Lamberts: George, Constant and Kit. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1986. ISBN 0-374-18283-3.

- Negra, Diane. Off-White Hollywood: American Culture and Ethnic Female Stardom. London: Routledge, 2001. ISBN 0-415-21678-8.

- Nugent, Frank. King of Chinatown (film review). The New York Times, March 16, 1939.

- Parish, James and William Leonard. "Anna May Wong." Hollywood Players: The Thirties. New Rochelle, New York: Arlington House Publishers, 1976, pp. 532–538. ISBN 0-87000-365-8.

- Performing Race on Screen. cinema.cornell.edu. Retrieved: May 12, 2008.

- Piccadilly (film review). Variety, July 24, 1929.

- Rollins, Peter C., ed. The Columbia Companion to American History on Film: How the Movies Have Portrayed the American Past. New York: Columbia University Press, 2003. ISBN 0-231-11223-8.

- Song (film review). The New York Times, August 22, 1928.

- Sweet, Matthew. "Snakes, Slaves and Seduction; Anna May Wong." The Guardian, February 6, 2008. Retrieved: March 20, 2008.

- The Toll of the Sea (film review). The New York Times, November 27, 1922.

- The Toll of the Sea (film review). Variety, December 1, 1922.

- Wang, Yiman and Catherine Russell, ed.. "The Art of Screen Passing: Anna May Wong's Yellow Yellowface Performance in the Art Deco Era." Camera Obscura 60: New Women of the Silent Screen: China, Japan, Hollywood. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press, 2005, pp. 159–191. ISBN 0-8223-6624-X.

- Wollstein, Hans J. "Anna May Wong." Vixens, Floozies, and Molls: 28 Actresses of late 1920s and 1930s Hollywood. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 1999. ISBN 0-7864-0565-1.

- Wong, Elizabeth: China Doll, The Imagined Life of an American Actress. Woodstock, Ill: Dramatic Publishing, 2005. ISBN 1-58342-315-X.

- Wood, Ean. The Josephine Baker Story. London: Sanctuary, 2000. ISBN 1-86074-286-6.

- Zia, Helen and Susan B. Gall. Notable Asian Americans. New York: Gale Research, 1995. ISBN 978-0-8103-9623-4.

Further reading

- Doerr, Conrad. "Reminiscences of Anna May Wong". Films in Review. New York, December 1968. ISSN 0015-1688.

- Griffith, Richard and Richard Mayer. The Movies. New York: Fireside, 1970. ISBN 0-600-36044-X.

- Schneider, Steven Jay, ed. 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die. Hauppauge, New York: Barron's Educational Series, 2005. ISBN 0-7641-5907-0.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Anna May Wong. |

- "The Anna May Wong Society". Archived from the original on 2012-03-27. Retrieved 2013-06-29.

- Anna May Wong at the Internet Movie Database

- Anna May Wong at the Internet Broadway Database

- Time Magazine: 'The Career of Anna May Wong'

- Anna May Wong Documentary Home

- Anna May Wong Documentary Women Make Movies

- Anna May Wong Tobacco Cards at Virtual History