Antisymmetric relation

In mathematics, a binary relation R on a set X is antisymmetric if there is no pair of distinct elements of X each of which is related by R to the other. More formally, R is antisymmetric precisely if for all a and b in X

- if R(a,b) and R(b,a), then a = b,

or, equivalently,

- if R(a,b) with a ≠ b, then R(b,a) must not hold.

As a simple example, the divisibility order on the natural numbers is an antisymmetric relation. And what antisymmetry means here is that the only way each of two numbers can be divisible by the other is if the two are, in fact, the same number; equivalently, if n and m are distinct and n is a factor of m, then m cannot be a factor of n.

In mathematical notation, this is:

or, equivalently,

The usual order relation ≤ on the real numbers is antisymmetric: if for two real numbers x and y both inequalities x ≤ y and y ≤ x hold then x and y must be equal. Similarly, the subset order ⊆ on the subsets of any given set is antisymmetric: given two sets A and B, if every element in A also is in B and every element in B is also in A, then A and B must contain all the same elements and therefore be equal:

Partial and total orders are antisymmetric by definition. A relation can be both symmetric and antisymmetric (e.g., the equality relation), and there are relations which are neither symmetric nor antisymmetric (e.g., the "preys on" relation on biological species).

Antisymmetry is different from asymmetry, which requires both antisymmetry and irreflexivity.

Examples

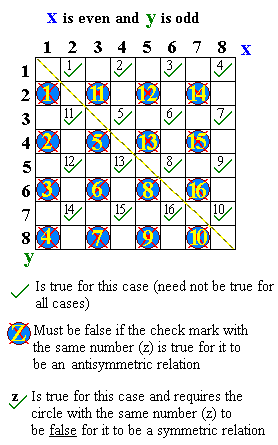

The relation "x is even, y is odd" between a pair (x, y) of integers is antisymmetric:

Every asymmetric relation is also an antisymmetric relation.

See also

References

- Lipschutz, Seymour; Marc Lars Lipson (1997). Theory and Problems of Discrete Mathematics. McGraw-Hill. p. 33. ISBN 0-07-038045-7.