Antigonus I Monophthalmus

| Antigonus I Monophthalmus Ἀντίγονος ὁ Μονόφθαλμος | |

|---|---|

| Basileus | |

.jpg) Coin of Antigonus, the Greek inscription reads "ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ ΑΝΤΙΓΟΝΟΥ" meaning [coin] of king Antigonus | |

| Reign | 306–301 BC |

| Coronation | 306 BC, Antigonia. |

| Predecessor | Alexander IV |

| Successor | Demetrius I |

| Born |

382 BC Elimeia, Macedon |

| Died |

301 BC (aged 81) Ipsus, Phrygia |

| Consort | Stratonice |

| Issue | Demetrius I, Philip |

| Dynasty | Antigonid dynasty |

| Father | Philip (the son of Machatas?) |

Antigonus I Monophthalmus (Ancient Greek: Ἀντίγονος ὁ Μονόφθαλμος, Antigonus the One-eyed, 382–301 BC), son of Philip from Elimeia, was a Macedonian nobleman, general, and satrap under Alexander the Great. During his early life he served under Philip II, and he was a major figure in the Wars of the Diadochi after Alexander's death, declaring himself king in 306 BC and establishing the Antigonid dynasty.

Biography

Career

Antigonus was appointed governor of Greater Phrygia in 333 BC. He was primarily responsible for defending Alexander's lines of supply and communication during the latter's extended campaign against the Achaemenid Persian Empire. Following Alexander's victory at Issus, the Persian mercenary commander Memnon of Rhodes ordered a counter-attack into Asia Minor in an attempt to sever Alexander's lines of supply and communication; however, Antigonus defeated the Persian forces in three separate battles.

As part of the division of the provinces after Alexander's death in 323 BC, Antigonus also received Pamphylia and Lycia from Perdiccas, regent of the empire, at the Partition of Babylon. He incurred the enmity of Perdiccas, the regent, by refusing to assist Eumenes to obtain possession of the provinces allotted to him, Paphlagonia and Cappadocia. Leonnatus had left with his army for Greece, leaving Antigonus alone to deal with Cappadocia, a task he apparently couldn't complete without additional aid.

Perdiccas seems to have viewed this as a direct affront to his authority and went up with the royal army himself to conquer the area. From there Perdiccas turned west towards Phrygia in order to humble Antigonus, who escaped with his son Demetrius to Greece, where he obtained the favour of Antipater, regent of Macedonia (321 BC), and Craterus.

With the death of Perdiccas in 321 BC, a new attempt at division of the empire took place at Triparadisus and Antigonus found himself entrusted with the command of the war against Eumenes, who had joined Perdiccas against the coalition of Antipater, Antigonus, Ptolemy, Craterus, and the other generals. Eumenes was defeated and forced to retire to the fortress of Nora (Greek: Νῶρα) in Cappadocia, and a new army that was marching to his relief was routed by Antigonus.

When Antipater died in 319 BC, he gave the regentship to Polyperchon, excluding Cassander, his son. Antigonus and the other dynasts refused to recognize Polyperchon, since it would undermine their own ambitions. He entered into negotiations with Eumenes, but Eumenes had already been swayed by Polyperchon, who also gave him authority over anyone within the empire. Effecting his escape from Nora, he raised an army and built a fleet in Cilicia and Phoenicia, and soon after formed a coalition with the satraps of the eastern provinces. Antigonus fought against Eumenes in two great battles at Paraitacene in 317 BC and Gabiene in 316 BC. Both were inconclusive, however. Yet in the aftermath of the second battle, Antigonus managed to capture the family and riches of the Silvershields, an elite regiment within Eumenes' army, who in turn handed over Eumenes to Antigonus in return for their release. After some deliberation, Antigonus had Eumenes executed.

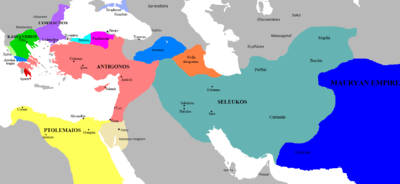

As a result, Antigonus now was in possession of the empire's Asian territories, his authority stretching from the eastern satrapies to Syria and Asia Minor in the west. He seized the treasures at Susa and entered Babylon. The governor of the city, Seleucus fled to Ptolemy and entered into a league with him, Lysimachus and Cassander (315 BC) against Antigonus. In 314 BC Antigonus invaded Phoenicia, under Ptolemy's control, and besieged Tyre for more than a year. His son Demetrius was defeated at the Battle of Gaza by Ptolemy in 312 BC, and after the battle, Seleucus made his way back to Babylonia. Seleucus returned to Babylon let him build up a base of his own, and he soon established control of the eastern satrapies. The Babylonian War began between Antigonus and Seleucus, where Seleucus defeated both Demetrius and Antigonus, and secured Babylonia.

After the war had been carried on with varying success from 315 to 311, peace was concluded, by which the government of Asia Minor and Syria was provisionally secured to Antigonus. This agreement was soon violated on the pretext that garrisons had been placed in some of the free Greek cities by Antigonus, and Ptolemy and Cassander renewed hostilities against him. Demetrius Poliorcetes, the son of Antigonus, wrested part of Greece from Cassander.

After defeating Ptolemy at the naval Battle of Salamis in 306 BC, Demetrius conquered Cyprus. Following the victory Antigonus assumed the title king and bestowed the same upon his son, a declaration that he now was independent from the empire. The other dynasts, Cassander, Ptolemy, Lysimachus and Seleucus, soon followed. He now prepared a large army and a formidable fleet, the command of which he gave to Demetrius, and hastened to attack Ptolemy in his own dominions. His invasion of Egypt, however, proved a failure; he was unable to penetrate Ptolemy's defences and was obliged to retire, yet inflicting high losses on Ptolemy. Demetrius in 305 BC attempted the reduction of Rhodes, which had refused to assist Antigonus against Egypt. The siege of Rhodes lasted a year and ended in 304 BC when Demetrius, meeting with obstinate resistance, was obliged to make a peace treaty upon the terms that the Rhodians would build ships for Antigonus and aid him against any enemy except for Ptolemy, on whom they bestowed the title Soter (savior) for his aid during the lengthy siege.

The dynasts unite against Antigonus

The most powerful dynasts of the empire, now kings in their own right, Cassander, Seleucus, Ptolemy and Lysimachus, responded to Antigonus's successes by allying with each other, often through marriage. Antigonus soon found himself at war with all four, largely because his territory shared borders with each of them. Once he had Cassander in a bad position, having gained the support of the Greeks and defeating him repeatedly, he demanded from Cassander the unconditional submission of Macedonia. Seleucus, Lysimachus and Ptolemy responded by joining forces and attacking him. Lysimachus invaded Asia Minor from Thrace, crossing the Hellespont. He had soon secured most of the Ionian cities, and Seleucus was on his way marching through Mesopotamia and Cappadocia. Antigonus was obliged to recall Demetrius from Greece, where his son had recently had a sterile encounter with Cassander in Thessaly; the two men, and their army, then moved against Lysimachus.

However, the army of father and son was defeated by the united forces of Seleucus and Lysimachus at the decisive Battle of Ipsus in 301 BC. Antigonus himself died in the battle after being struck by a javelin, in the eighty-first year of his life. Prior to Ipsus, he had never before lost a battle. With his death, any plans the court of Antigonus may have had of reuniting Alexander's empire came to an end. Antigonus's kingdom was divided up, with most ending up in the hands of new kingdoms under Lysimachus and Seleucus. The victors largely followed Antigonus's precedent and had themselves named as kings, but they did not claim power over the erstwhile empire of Alexander nor each other. Instead, these kings established a troubled (and in the end failed) modus vivendi with each other, and accepted their kingdoms as separate realms.

Meanwhile, Antigonus's surviving son Demetrius took control of Macedon in 294 BC; Antigonus's descendants held this possession, off and on, until it was conquered by the Roman Republic at the Battle of Pydna in 168 BC.

Monophthalmus in historical fiction

Mary Renault, in Funeral Games, translates the sobriquet into English: "One Eye."

In the 2004 Oliver Stone film Alexander, Antigonus is played by Ian Beattie.

Antigonus appears (under the Greek form of his name, Antigonos) in L. Sprague de Camp's historical novel, The Bronze God of Rhodes.

References

- Austin, M. M. (1981). The Hellenistic World from Alexander to the Roman Conquest: A Selection of Ancient Sources in Translation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- The contemporary Babylonian Chronicles, especially the Chronicle of the Diadochi (= ABC 10 = BCHP 3).

- Bar-Kochva, B. (1976). The Seleucid Army. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Billows, Richard A. (1990). Antigonos the One-Eyed and the Creation of the Hellenistic State. Berkeley and Los Angeles, California: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-20880-3.

- De Ste. Croix, G.E.M. (1981). The Class Struggle in the Ancient Greek World: From the Archaic Age to the Arab Conquests. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Diodorus Siculus xviii., xx. 46-86

- Gardner, Jane F. (1974). Leadership and the Cult of Personality. London: Dent.

- Gruen, Erich S. (1984). The Hellenistic World and the Coming of Rome. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Justin xv. 1-4

- Köhler, "Das Reich des Antigonos," in the Sitzungsberichte d. Berl. Akad., 1898, p. 835 f.

- Nepos, Eumenes

- Plutarch, Demetrius, Eumenes

- Simpson, R. H. (1959). "Antigonus the One-Eyed and the Greeks". Historia. 8: 385–409.

- Walbank, R. W. (1981). The Hellenistic World. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

-

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Antigonus Cyclops". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Antigonus Cyclops". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

External links

- A genealogical tree of Antigonus

- Antigonus I Monophthalmus entry in historical sourcebook by Mahlon H. Smith

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by - |

Antigonid dynasty 306–301 BC |

Succeeded by Demetrius I of Macedon |