Apache Scouts

| Apache Scouts | |

|---|---|

|

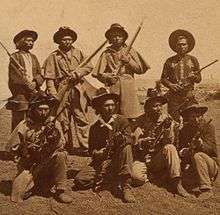

Apache scouts at Fort Apache, Arizona in the 1880s | |

| Active | 1860s - 1947 |

| Country |

|

| Branch |

|

| Type | Indian scouts |

| Engagements |

Chiricahua War |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders |

George Crook Albert Sieber Tom Horn |

The Apache Scouts were part of the United States Army Indian Scouts, most of their service was during the Apache Wars up to 1886 though the last scout retired in 1947. The Apache scouts were the eyes and ears of the United States military and sometimes the cultural translators for the various Apache bands and the Americans. Apache scouts also served in the Navajo War, the Tonto War, the Mexican Border War and they saw stateside duty during World War II. There has been a great deal written about Apache scouts, both as part of United States Army reports from the field and more colorful accounts written after the events by non-Apaches in newspapers and books. Men such as Al Sieber and Tom Horn were sometimes in charge of small groups of Apaches. As was the custom in the United States military, scouts were enlisted with Anglo nicknames or single names. Many Apache scouts received citations for bravery.

Apache Scouts by band

It is important to note that Apaches were lumped together as a group by outsiders. However, while they may have shared many similar customs and language, they defined themselves by loose bands which tended to be associated with a geographical area. A band was semi nomadic and had clan and kinship ties with neighboring groups. Thus, a Western Apache band did not have many ties to an Eastern Apache band and might be very distrustful. Apache scouts were usually grouped in operational units by band.

Tonto Apache scouts were recruited to assist General Crook find Chief Delshay's band who fled the Fort Verde reservation. Crook's Chief of Scouts, Albert Sieber always seemed to have his Tonto scouts with him through the Apache Wars.

White Mountain scouts served with Company B under Lieutenant Charles B. Gatewood from Fort Apache in 1885 to 1886. General George Crook had high praise for this group which is composed of several bands. "Chiricahuas were the most subordinate, energetic, untiring and, by odds, the most efficient of their command." These scouts were sent to Florida by General Miles, along with those who they tracked for sixteen months in 1885 and 1886, as if these Apache scouts were hostiles to be punished. They were kept captive under nominal arrest as prisoners of war, along with the rest of Geronimo's band whom they'd helped the army track down, for twenty-six years before finally being released.

Warm Springs Apache scouts served in Company B under Lieutenant Britton Davis and were in the field tracking Geronimo and Nana. In 1885 Mescalero scouts were with Major Vanm Horn cavalry which was trying to prevent Geronimo, Nana and others from crossing the Rio Grande near Fort Stanton.

Service History

Navajo War

Mescalero Apache scouts served with the army during the Navajo War in 1863 and 1864. One of the last battles of the war involving the scouts occurred along the Pecos River of New Mexico Territory on January 4, 1864. After a band of about 100 Navajo warriors raided the reservation at Bosque Redondo, the local Indian agent led sixty Mescalero's south in the pursuit of the raiders and eventually caught up with them at the Pecos. When the fighting started, the Navajo realized they couldn't escape with their herd of stolen livestock so they took up defensive positions to try to fight off their pursuers. Initially, the Navajo were successful in keeping their enemies back, but, eventually, United States Army reinforcements began to arrive. After a long battle the Navajo were forced to retreat without the livestock, leaving an estimated forty dead on the field. Another twenty-five Navajos were estimated to have been wounded and a group the same size escaped. There were no casualties among the Americans or the Apache scouts and they recovered fifty horses and mules. Less than two weeks later Colonel Kit Carson would lead an expedition into Canyon de Chelly, the heart of Navajo territory, capturing most of the inhabitants and ending the war.[1]

Yavapai War

Apache scouts were employed by the United States Army throughout most of the Apache Wars but it wasn't until about 1870 when General George Crook introduced the idea of enlisting entire companies of scouts. However, at that time, few Apaches were willing to join Crook so he was forced to recruit native Americans from various tribes across the Southwest. The majority of Crook's scouts were Apache, divided into two companies, but at first there were also Navajos, Pimas, Yaquis, Opatas, Papagos, Walapais, Yavapais, and Paiutes, as well as some Mexicans and Americans. General Crook allowed any captured Apache male to join his scouts, believing that "the wilder the Apache was, the more he was likely to know the wiles and statagems of those still out in the mountains. (sic)" While Crook was recruiting natives to fight for him, he was also fighting against the Western Apaches and the closely associated Yavapai tribe in central Arizona Territory. During the Tonto Basin Campaign in 1872, Crook deployed his scouts at the Battle of Salt River Canyon on December 28. Over 100 Yavapai and Tonto men, women and children were held up inside a cave overlooking the Salt River. With some 130 cavalrymen, and about thirty scouts, Crook attacked the cave, killing seventy-six people, including non combatants, and capturing the remaining thirty-four. The general followed up the victory with another at Turret Peak, on March 27, 1873, in which another fifty-seven Yavapais and Tonto Apaches were killed. Only one man was killed on the Americans' side during both engagements and soon after the Yavapai and the Tontos began flocking to Camp Verde to surrender.[2][3][4]

The war was not over yet though, small bands of Yavapai and Apache raiders continued to harass the army and the settlers in and around Tonto Basin for two years more. The fighting was mostly skirmishing, but it was enough to keep the scouts busy. One of these skirmishes occurred on November 1, 1874 after Tonto Apaches stole some livestock from a rancher. Some forty Apache scouts and cavalrymen were then dispatched from Camp Verde to pursue the hostiles and they caught up with them at Sunset Pass, near the Little Colorado River. During the fight that ensued, Lieutenant Charles King was badly wounded in the arm and temporarily stranded. King was rescued by his men who engaged the hostiles for some time, but, eventually, the order to retreat was given. King later wrote a book, titled "Sunset Pass", about his experiences serving with the Apache scouts in Arizona Territory. After the war ended, General Crook departed Arizona for Dakota Territory in 1876. Colonel Augustus P. Kautz took over the command of the scouts and he formed a third company in early 1877 and a fourth in 1878. Upon taking command of the scouts, Kautz wrote; "These scouts supported by a small force of cavalry, are exceedingly efficient, and have succeeded, with one or two exceptions, in finding every party of Indians they have gone in pursuit of. They are a great terror to the runaways [renegades] from the Reservations, and for such work are more efficient than double the number of soldiers. (sic)"[2][5]

Border War

Following Geronimo's surrender in 1886, there was little need for Apache scouts so their ranks were thinned down to just fifty men by 1891. In 1915 there were only twenty-four left. However, after Pancho Villa's attack on Columbus, New Mexico, in March 1916, General John J. Pershing was ordered to command a punitive expedition into Mexico to capture or kill Villa. Accordingly, Pershing authorized the enlistment of seventeen new Apache scouts, raising their strength to thirty-nine men. Pancho Villa and his rebels were operating in Chihuahua when Pershing led his army across the international border; the terrain was rugged desert, littered with canyons and other concealed positions, making the pursuit of Villa difficult for the army, but not for the Apaches. The scouts were divided into two groups, though they engaged in only two small skirmishes, they had plenty of opportunities to use their tracking abilities against the Villistas and army deserters. The first group headed into Mexico from Fort Huachuca, Arizona, to join up with the 10th Cavalry Buffalo Soldiers, while the second group departed from Fort Apache, to join the 11th Cavalry. However, by the time the scouts arrived in Chihuahua, Mexico, the hunt for Villa was already suspended by Pershing, due to the defeat in the Battle of Carrizal, in which the Americans engaged Mexican government troops, known as Carrancistas. The hunt was never continued and after that Pershing began an occupation of northern Chihuahua, followed by a slow withdrawal back to the United States, under President Wilson's orders.[6][7]

The first battle involving the scouts was fought at Ojo Azules Ranch. On May 5, a small group of scouts joined up with a troop from the 11th Cavalry to attack about 150 Villistas. During the half-hour battle that followed, the Apaches played a significant role. In all sixty-one Mexicans were killed and another seventy were captured, all without sustaining any casualties. In April 1917, Captain James A. Shannon, 11th Cavalry, wrote an article titled With the Apache Scouts in Mexico, which described the tactics employed by the scouts and his experiences with them. Shannon wrote the following: "The Indian cannot be beaten at his own game. But in order to get results, he must be allowed to play that game in his own way. You tell a troop of white soldiers there is an enemy a thousand yards in your front and they will go straight at him without questions. The Indian under the same circumstance wants to look it all over first. He wants to go to one side and take a look. Then to the other side and take a look. He is like a wild animal stalking its prey. Before he advances he wants to know just what is in his front. This extreme caution, which we dont like to see in the white man, is one of the qualities that makes him a perfect scout. It would be almost impossible to surprise an outfit that had a detachment of Apache scouts in its front. They do not lack courage by any means. They have taken part in some little affairs in Mexico that required plenty of courage, but they must be allowed to do things in their own way. (sic)"[6][8]

The second battle involving the scouts occurred on June 1, 1916 at Las Varas Pass after some Villistas stole a pair of United States Army horses from the 5th Cavalry. Captain Shannon wrote; "They started off on the trail and after going a short distance came to a rocky stretch where the trail was hard to follow. They circled out like a pack of hounds and soon one of them gave a grunt and all the rest went over where he was and started off again. After a while the trail seemed to divide, so the detachment split up into two parties following the two trails. After about an hour or so, one of these parties overtook the villistas in a very narrow ravine. They shot two of them, and on account of the narrowness of the pass, unfortunately shot two of the horses, one of which proved to be the private horse of Lieutenant Ely of the Fifth Cavalry. They recovered one government horse and got some Mexican saddles, rifles, etc. (sic)"[6][8]

After the expedition ended in February 1917, the Apache scouts were once again without a real purpose for existence so the army disbanded about half of the force, leaving twenty-two scouts for duty. Their war-time service was not completely over though, conflict between the United States Army and Mexicans continued until 1919 and Mexican raids across the border were a frequent occurrence into the 1920s.[6]

See also

- Traditional Apache scout

- Navajo Scouts

- Pawnee Scouts

- Crow Scouts

- Black Seminole Scouts

- Chatto (Apache)

- Crawford Affair

References

Sources

- Thrapp, Dan L. (1995). Al Sieber: Chief of Scouts. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-2770-8.

- Anon (1956). Record of Enlistments in the United States Army,"Volumes 150-151 (1866-77) Indian Scouts. Washington D.C.: National Archives [Microcopy 233].

- Thrapp, Dan L. (1979). The Conquest of Apacheria. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-1286-7.

- Bourke, John G. (1980). On the Border with Crook. Time-Life Books. ISBN 0-8094-3585-3.

- Michno, Gregory (2003). Encyclopedia of Indian wars: western battles and skirmishes, 1850-1890. Mountain Press Publishing. ISBN 0-87842-468-7.

- Beede, Benjamin R. (1994). The War of 1898, and U.S. interventions, 1898-1934: an encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0-8240-5624-8.

- Boot, Max (2003). The Savage Wars of Peace: Small Wars and the Rise of American Power. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 046500721X. LCCN 2004695066.