Assumption Chapel

Coordinates: 45°27′21″N 94°24′51″W / 45.45583°N 94.41417°W

Assumption Chapel, also known as the Grasshopper Chapel, was built in petition for relief from the Grasshopper Plagues of the 1870s. The Chapel is situated on the top of a hill on the outskirts of Cold Spring, Minnesota. Pilgrimage Road winds up the steep hill first lined with huge lilac bushes and then shrouded by enormous trees. The top of the hill is covered with lush grass and more trees. In the midst of a clearing in the trees stands the granite form of the Chapel.

History

Plagues

The first chapel built on this site was known as Maria Hilf, which means "Mary's Help" in German. At the time of its original construction in 1877 much of the Midwest was suffering from locust plagues. The plagues began in the summer of 1873, when Rocky Mountain Locust left the home for which they are named and laid claim to a territory spreading from southern Wyoming over Nebraska and the Dakotas all the way to Iowa and Minnesota.[1]

The first year the grasshoppers came looking for food and found it in the plentiful wheat fields, where they laid eggs. The newly hatched fledgling grasshoppers were wingless for the first six to eight weeks but their work was no less devastating for the lack of wings. Until they could fly they crawled along and feasted on the tender, new growth of crops. When their wings grew strong enough they flew off for another field. This cycle would continue from 1873 to 1877, bringing widespread destruction to a part of the country primarily dependent on an agricultural economy.

Large black clouds made up of thousands of grasshoppers moved from field to field, from county to county.[1] One historian reported that "grasshoppers, sixty to eighty per square yard, could devour one ton of hay per day each forty acres they covered."[2] The grasshoppers ate everything and anything: crops, fruit trees, wooden fork handles and even items of clothing.[1] In her book On the Banks of Plum Creek, Laura Ingalls Wilder records her eyewitness accounts of the plight of these plagues. She relates how they could not even keep grasshoppers out of the milk pail while milking.[3] She tells how some of the men headed to the eastern side of the state to find work with the harvest as those farms had not been infected with the grasshoppers.[3]

The farmers who stayed to fight the plague tried anything and everything to overcome the grasshopper plague. Some used smudge pots to keep the grasshoppers in flight. Others set their doomed crops on fire in order to kill the fledgling grasshoppers. Many farmers resorted to catching them by hand or in buckets. People started building makeshift "hopper dozers". These machines were basically a piece of sheet metal smeared with tar which would be dragged over the field. The grasshoppers would get stuck in the tar and be wiped off and burned at each end of the field and then the "hopper dozer" would make another pass.[1] Unfortunately the grasshoppers devastated crops at a speed that no human invention could compete with.[1]

The number of grasshoppers and the destruction they brought with them grew with each consecutive year. By the spring of 1877, grasshopper eggs covered approximately two thirds of Minnesota.[2] Each year the Minnesota State Legislature appropriated more and more funds to assist its distressed citizens with the purchase of seed and even the necessities of food and clothing.[2] By the beginning of the fifth year of the plagues the damage was nearly complete. Manmade inventions failing, the people turned to spiritual means to relieve the suffering and devastation of the plague. Minnesota governor John S. Pillsbury declared April 26, 1877, a statewide day of prayer.[4] That night and the following day the weather shifted and the rain which fell soon turned to snow.[1] The people thought this could be the event to impede the grasshoppers' destructive advances, but when the storm passed they were as plentiful as ever.

The chapel

In Stearns County, about a month after the State wide day of Prayer, newly ordained Father Leo Winter, OSB, was assigned to the Parish of St. James in Jacobs Prairie with the mission of St. Nicholas some eight miles away.[2] In the midst of the ongoing devastation Father Winter encouraged the people to continue their prayers of supplication.[2] Father Winter felt that they should petition the Virgin Mary to intercede for them to God for relief from the grasshoppers.[5] Father Winter talked over the idea with fellow parishioners. They decided to build a chapel in Mary’s honor and to offer Masses of Thanksgiving every Saturday.[2]

The parishioners of the two parishes agreed. They would build a chapel "to honor the mother of God, to take refuge in her as their intercessor and be freed from the ravages of the grasshopper plague."[5] Two farmers donated seven acres half way between the two parishes of St. James and St. Nicholas.[2] Construction on the Chapel began July 16, 1877.[2] Laura Ingalls Wilder recorded that the grasshoppers left suddenly, one day in July. They rose up and flew West from whence they had come.[3]

All told, the chapel cost a total of $865 and was complete in less than a month.[2] The day after completion, August 15, 1877, Father Winter consecrated the altar and celebrated the first Mass.[2] According to a document signed and notarized with six witnesses, by the time the second mass was offered on September 8, 1877, not one grasshopper could be found.[2]

Legacy

The grasshoppers did not return in the spring of 1878 and they had not stayed long enough to lay their eggs the previous summer. In fact there has not been grasshopper plague in Minnesota or the Midwest since 1877.[2] The masses in Maria Hilf continued as promised and the farmers began to rebuild their farms which afforded bountiful harvests the very next year. The original chapel was destroyed June 28, 1894, by a tornado.[2] The wooden chapel was picked up and smashed into a grove of trees where, for over a hundred years, those twisted trees stood as a reminder of the tragedy. Everything had been ruined except for the statue of the Virgin Mary which lay unharmed in the rubble of the chapel.[2] The hill would stand vacant for fifty-eight years.

Description

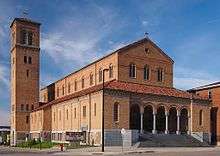

In 1952, in honor of the centennial of the diocese of Saint Cloud, the Chapel was rebuilt. The current chapel stands sixteen by twenty-six, the approximate size of the original chapel.[2] It is constructed of rough granite, much of which was donated by the Cold Spring Granite Company, a major local business.[5] The inside of the Chapel is simple and has no pews, only an altar. The chapel walls are made of polished agate and carnelian granite.[2] Four simple stained glass windows enhance the interior of the chapel. Above the altar stands the wooden statue that had been carried in procession through the Cold Spring community at the time of the Chapel's original consecration. The most telling feature and testimony to the history of the chapel is the stone carving above the door. It is inscribed "Assumpta est Maria" ("Mary has been taken up"), referring to the new name given to this reconstructed chapel. Mary is pictured between the words but at her feet, bowing in submission, are two kneeling grasshoppers.

Today

This new chapel was dedicated on October 7, 1952.[2] Today, in continuation of the hundred and thirty-odd year old promise there is an annual August 15 Mass celebrated on the Hill. Also, since 1990, for nine consecutive weeks in May and June, Mass is celebrated on Thursday evenings; a novena for the intention of a safe planting season and a good harvest. The surrounding parishes take turns celebrating the mass.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Atkins, Annette (1984). Harvest of Grief. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Voigt, Robert J. (1993). The Story of Mary and the Grasshoppers. Cold Spring, MN.

- 1 2 3 Wilder, Laura Ingalls (1965). On the Banks of Plum Creek. New York: Harper & Row Publishers.

- ↑ "Assumption Chapel" accessed April 5, 2011.

- 1 2 3 Gross, Stephen John (April 2006). "The Grasshopper Shrine at Cold Spring, Minnesota: Religion and Market Capitalism among German-American Catholics" (PDF). The Catholic Historical Review. 92 (2): 215–243. doi:10.1353/cat.2006.0133.