Attacker-class escort carrier

HMS Attacker | |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Attacker class |

| Builders: |

|

| Operators: | Royal Navy |

| Preceded by: | Avenger class |

| Succeeded by: | Ruler class |

| Built: | 1941–1943 |

| In commission: | 1942–1946 |

| Planned: | 8 |

| Completed: | 8 |

| Retired: | 5 |

| Scrapped: | 3 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type: | Escort carrier |

| Displacement: | 11,420 long tons (11,600 t) |

| Length: | 492 ft (150 m) |

| Beam: | 69.5 ft 6 in (21.34 m) |

| Draught: | 23.25 m (76.3 ft) |

| Installed power: | 9,350 shp (6,970 kW) |

| Propulsion: |

|

| Speed: | 17 knots (31 km/h; 20 mph) |

| Complement: | 646 |

| Armament: |

|

| Aircraft carried: | 24 |

| Aviation facilities: |

|

Attacker-class escort carriers were a type of aircraft carrier in service with the British Royal Navy during the Second World War. There were eight ships in the class, all constructed in the United States and supplied under the terms of Lend-Lease to the Royal Navy.

The ships served in two different roles: as convoy escort carriers, equipped with both anti-submarine and fighter aircraft, and as strike carriers, equipped with just fighter aircraft. When used as convoy escorts, the ships' aircraft were successful in deterring German submarines from attacking Allied convoys, with a number of German submarines and aircraft destroyed or damaged by the aircraft. Those carriers operating in the strike role took part in two major landings in the Mediterranean and an operation against the German battleship Tirpitz in Norwegian waters. Seven of the ships ended the war in the Far East in the campaigns against the Japanese Empire and were then used to transport home prisoners of war.

All eight ships survived the war and were eventually returned to the United States Navy, which sold five of them for conversion into merchant ships. The other three ships were scrapped.

Design and description

The Attacker class comprised eight ships built in the United States for the Royal Navy during the Second World War.[1][2] They were all built between 1941 and 1942 by Ingalls Shipbuilding or Western Pipe & Steel shipyards; both companies completed four ships.[1] They were then supplied under the terms of Lend-Lease to the Royal Navy for their use. The ships had a complement of 646 men. Crew accommodations were significantly different from the normal for the Royal Navy at the time. Instead of food being prepared by separate messes, it was cooked in the galley and served cafeteria-style in a central dining area. Unlike British-built ships, they were equipped with a modern laundry and a barber shop. The traditional hammocks were replaced by three-tier bunk beds, 18 to a cabin, which were hinged and could be tied up to provide extra space when not in use.[3]

The ships had an overall length of 492.25 feet (150.04 m), a beam of 69.5 feet (21.2 m), and a height of 23.25 ft (7.09 m). They displaced 11,420 long tons (11,600 t) at deep load.[4] Propulsion was provided by two steam turbine engines connected to one shaft, giving 8,500 brake horsepower (BHP), which could propel the ship at 17 knots (31 km/h; 20 mph).[5]

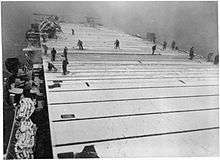

All the escort carriers had the capacity for up to 24 anti-submarine or fighter aircraft, which could be a mixture of the British Hawker Sea Hurricane, Supermarine Seafire, and Fairey Swordfish, and the American Grumman Wildcat, Vought F4U Corsair and Grumman Avenger.[4] The exact composition of the embarked squadrons depended upon the mission. Some squadrons were composite squadrons for convoy defence, and would be equipped with anti-submarine and fighter aircraft,[6] while other squadrons working in a strike-carrier role would only be equipped with fighter aircraft.[7] Aircraft facilities consisted of a small combined bridge–flight control on the starboard side above the 450-by-120-foot (137 by 37 m) flight deck,[8] two aircraft lifts measuring 42 by 34 feet (13 by 10 m), and nine arrestor wires. Aircraft could be housed in the 260 by 62 feet (79 by 19 m) hangar below the flight deck.[4]

The ships' armament concentrated on anti-aircraft (AA) defence and comprised two 4-inch AA guns in single mounts, eight Bofors 40 mm AA guns in twin mounts, and 21 Oerlikon 20 mm AA cannons in single or twin mounts as the standard fit.[4] In practice all the ships had slightly different weapons mounted. Attacker, Chaser, and Hunter only had four single 20 mm AA cannons, the rest being double mounts. Of the other ships, Battler had two, Stalker had six, and Fencer had seven single 20 mm cannons. Pursuer had four extra 40 mm AA guns, and Striker had six extra in place of twin 20 mm mounts.[9]

Before any of these ships entered service with the Royal Navy, they went to Burrards shipbuilders in British Columbia for some modifications. These modifications, 150 of them in total, were paid for by the Canadian government.[10] Further modifications to turn the escort carriers into assault carriers were undertaken by the Caledon Shipbuilding & Engineering Company in Dundee, Scotland. This included installing over 100 telephones in a shipboard network. A new briefing room with an army plot for operations ashore was installed and extra cabins were built, providing an additional 140 bunks.[11] The carriers were also fitted for a secondary role of providing oil and provisions for their accompanying destroyers. Fueling could be a lengthy process and was done on the move. It took 40 minutes from firing a line across to starting to pump oil, two hours to pump 96 long tons (98 t) of oil, and a further 35 minutes to disconnect the hose and secure the equipment.[12]

Service history

| Ship | Builder | Laid down | Launched | Commissioned | Fate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HMS Attacker | Western Pipe, San Francisco, California | 17 April 1941 | 27 September 1941 | 10 October 1942 | Returned 5 January 1946, later SS Castel Forte |

| HMS Battler | Ingalls Shipbuilding, Pascagoula, Mississippi | 15 April 1941 | 4 April 1942 | 15 November 1942 | Scrapped 1946–48 |

| HMS Chaser | Ingalls Shipbuilding, Pascagoula, Mississippi | 28 June 1941 | 15 January 1942 | 9 April 1943 | Returned 12 May 1946, SS Aagtekerk |

| HMS Fencer | Western Pipe, San Francisco, California | 5 September 1941 | 4 April 1942 | 20 February 1943 | Returned 11 December 1946, SS Sydney |

| HMS Hunter | Ingalls Shipbuilding, Pascagoula, Mississippi | 15 May 1941 | 22 May 1942 | 11 January 1943 | Returned 29 December 1946, SS Almdijk |

| HMS Pursuer | Ingalls Shipbuilding, Pascagoula, Mississippi | 31 July 1941 | 18 July 1942 | 14 June 1943 | Scrapped 1946–48 |

| HMS Stalker | Western Pipe, San Francisco, California | 6 October 1941 | 5 March 1942 | 30 December 1943 | Returned 29 December 1945, SS Riouw |

| HMS Striker | Western Pipe, San Francisco, California | 15 December 1941 | 7 May 1942 | 29 April 1943 | Scrapped 1946–48 |

| HMS Tracker | Seattle-Tacoma Shipbuilding Corporation, Tacoma, Washington | 3 November 1941 | 7 March 1942 | 31 January 1943 | Sold into merchant service as the Corrientes. Scrapped in 1964. |

Convoy escorts

Escort carriers were designed to accompany other ships, forming the escort for convoys.[13] The anti-submarine aircraft employed were initially Fairey Swordfish and later Grumman Avengers, which could be armed with torpedoes, depth charges, 250-pound (110 kg) bombs, or the RP-3 rocket projectile.[14] As well as carrying out their own attacks on U-boats, these aircraft identified target locations for the convoy's escorts to attack.[15] Typically anti-submarine patrols would be flown between dawn and dusk. One aircraft would fly about 10 miles (16 km) ahead of the convoy, while another patrolled astern. Patrols would last between two and three hours, using both radar and visual observation in their search for U-boats.[16] By 1944, it was usual to have two escort carriers working as a pair on convoy escort. Experience had shown it was best to have two composite squadrons. One squadron included fighters and the by then obsolete Fairey Swordfish equipped with air-to-surface vessel (ASV) radar for night patrols. The other squadron would be equipped with fighters and the Grumman Avenger for long-range day patrols, as they could not be fitted with the ASV radar.[17]

The Fleet Air Arm squadrons flying off the Attacker class escort carriers did have some successes of their own. The first of six confirmed U-boats destroyed by aircraft flying off Attacker class ships was on 10 February 1944, when two Fairey Swordfish from the 842 Naval Air Squadron on board Fencer sank U-666 west of Iceland.[15][18] On 4 March, while on Arctic convoy patrol, Fairey Swordfish from 816 Naval Air Squadron on board Chaser so severely damaged U-472 with a salvo of RP-3 rockets that she could not submerge and was sunk by HMS Onslaught. For the rest of the day Chaser's Fairey Swordfish kept the U-boats at bay by identifying their locations to her escorts. They also damaged two other U-boats themselves.[15][19] The U-366 was sunk by RP-3 rockets fired from a Fairey Swordfish on 5 March,[15] and the U-973 on 6 March. Three other U-boats sighted managed to evade an attack in foggy conditions.[20][21] Operating from Fencer, 842 Squadron sank their second submarine, U-277, on 1 May,[22] and sunk U-959 and U-674 on 2 May 1944.[15][20]

The carriers' aircraft could also claim some success against the Luftwaffe's long-range bombers. On 1 December 1943, two Grumman Wildcats from 842 Naval Air Squadron on board Fencer shot down a Focke-Wulf Fw 200 that was spying on Convoy OS 60.[23] The next confirmed air-to-air success came on 24 February 1944, when four Grumman Wildcats from 881 Naval Air Squadron on board Pursuer were scrambled after the ship's radar had identified at least three aircraft approaching. The approaching bombers comprised a mixed force of seven Focke-Wulf Fw 200 and Heinkel He 177s carrying glider bombs. One Fw 200 and one He 177 were shot down by Grumman Wildcats. The rest of the Germans kept their distance due to the combined efforts of the fighters and the ships' anti-aircraft fire.[24] Off Cape Finisterre in March 1944, Grumman Wildcat fighters from Pursuer shot down a Heinkel He 177 and a Focke-Wulf Fw 200, and damaged a Fw 200.[25] In August 1944, the Arctic convoys had started again, the first one being escorted by Striker and HMS Vindex, a British-built escort carrier. On board Striker was 824 Naval Air Squadron with twelve Fairey Swordfish IIs, ten Grumman Wildcat Vs, and two spares. The Grumman Wildcats shot down a Blohm & Voss BV 138 on 22 August.[26] For Operation Neptune from 5 June 1944 to the middle of the month, five all-fighter escort carriers, including Fencer, provided air cover to protect the anti-submarine groups on the flanks of the Normandy invasion fleet.[27]

Strike operations

During the Salerno landings, Force V, commanded by Admiral Philip Vian and consisting of Attacker, Battler, Hunter, and Stalker, along with the light fleet carrier Unicorn, provided air cover. The five carriers were expected to keep a fighter aircraft force of 22 Supermarine Seafires over the landing area until the ground forces had seized an Italian airfield for use by ground-based aircraft.[28] On the first day, 9 September 1943, they flew 265 sorties. They had expected to be relieved by 10 September, but a suitable airfield was not captured until 12 September.[29] Of the carriers' 105 fighters, ten were lost in action and 33 written off in accidents. In exchange, they claimed two German aircraft destroyed and four others probably destroyed.[30] For the landings in the south of France on 15 August 1944, Attacker, Stalker, and Hunter, each equipped with 24 Supermarine Seafires and Pursuer, with 24 Grumman Wildcats, formed part of the aircraft carrier force dubbed Task Force 88.[7]

The success of the Allied navies against U-boats in the Atlantic forced the Germans to move some of them into the Indian Ocean. To counter this threat, a task force was formed with HMS Battler, the cruisers Suffolk and Newcastle, and the destroyers Quadrant and Roebuck. Their objective was to locate and destroy the U-boats and their supply ships and protect the shipping lanes between India, Aden, and South Africa. In March 1944, one of Battler's planes sighted the German supply ship Brake and three surfaced U-boats. They guided the Roebuck to the supply ship, which was scuttled by her captain. The three U-boats submerged before the start of the action.[31]

In April 1944, aircraft from Fencer and Pursuer took part in Operation Tungsten: the attack on the German battleship Tirpitz in the Kaafjord and at Tromsø.[22] Fairey Barracuda bombers from HMS Victorious were escorted by Supermarine Seafires, Vought Corsairs, Grumman Hellcats, and from the two escort carriers, Grumman Wildcats. The Hellcats carried out attacks on the anti-aircraft defences and the Wildcats attacked the Tirpitz with machine gun fire, just prior to the Fairey Barracudas bombing run.[32] Tirpitz was hit multiple times during the attack, killing over 100, and wounding over 300, of her crew. There was some damage to her superstructure but no bombs pierced the armoured deck.[33]

On 26 April 1944, Pursuer's aircraft successfully attacked a German convoy off Bodø in northern Norway. The convoy consisted of four merchant ships and five escorts; of these, all the merchant ships and one of the escorts were bombed and three of the merchant ships were set on fire. At the same time, other aircraft bombed and set on fire a large merchant ship at Bodø Harbour.[34] On 6 May 1944, while on an anti-shipping sweep in the same area, Grumman Wildcats of 882 Naval Air Squadron from Searcher shot down two Blohm & Voss BV 138 seaplanes.[35]

Early in 1944, the trend was for the strike carrier to move eastwards. Firstly Attacker, Hunter, and Pursuer were sent to the Aegean sea to conduct operations against Axis garrisons in the area.[13] They then moved to the Indian Ocean, joining Fencer and Stalker in supporting the Allied armies in Burma. Here they supported the Fourteenth Army amphibious landings and interdicted Japanese shipping in the Bay of Bengal and the Straits of Malacca. As the war in the east progressed, the British and U.S. Pacific fleets combined. Two more Attacker-class ships arrived in the area, Chaser and Striker. These were used to ferry replacement aircraft for the other carriers, and after the Japanese surrender were given another role: repatriating prisoners of war.[13]

When the war was over, the surviving Lend-Lease ships were returned to the U.S. Navy, which now had a surplus of these ships, so some were sold into merchant service. HMS Attacker became Costel Forte, HMS Chaser Aagtekerk, HMS Fencer Sydney, HMS Stalker Rionw, and HMS Hunter Almdijk. The other three Attacker-class ships, HMS Battler, HMS Pursuer, and HMS Striker, were not sold into merchant service; all three were scrapped between 1946 and 1948.[13][36]

Battle honours

All eight ships were awarded battle honours by the Royal Navy.

- HMS Attacker: Atlantic 1943–1944, Salerno 1943, South France 1944, Aegean 1944

- HMS Battler: Atlantic 1942–1945, Salerno 1943

- HMS Chaser: Atlantic 1943, Arctic 1944, Okinawa 1945

- HMS Fencer: Atlantic 1943–1944, Norway 1944, Arctic 1944

- HMS Hunter: Atlantic 1942–1944, Salerno 1943, South France 1944, Aegean 1944, Burma 1945, Malaya 1945

- HMS Pursuer: Atlantic 1943–1945, Norway 1944, Normandy 1944, South France 1944, Aegean 1944, Atlantic 1944, Norway 1945, Arctic 1945

- HMS Stalker: Atlantic 1943–1944, Salerno 1943, South France 1944, Aegean 1944, Burma 1945

- HMS Striker: Atlantic 1943–1944, Arctic 1944, Norway 1944, Okinawa 1945[37]

Notes

- 1 2 Cocker (2008), p. 79.

- ↑ Morison (2002), p. 344.

- ↑ Poolman (1972), pp. 74–75.

- 1 2 3 4 Cocker (2008), p. 80.

- ↑ Cocker (2008), pp. 80–81.

- ↑ Poolman(1972), p.98.

- 1 2 Morison (2002), p.342.

- ↑ Poolman (1972), p.57.

- ↑ Friedman (1988), p.188.

- ↑ Poolman (1972), pp. 88–89

- ↑ Poolman (1972), p. 89.

- ↑ Poolman (1972), pp. 102–103

- 1 2 3 4 Poolman (1972), p.155

- ↑ Poolman (1972), p.135.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Cocker (2008) p.147

- ↑ Poolman (1972), p.79.

- ↑ Poolman (1972), p.118.

- ↑ Poolman (1972), p.116.

- ↑ Poolman (1972), p.127.

- 1 2 Cocker (2008), p.148.

- ↑ Poolman (1972), p.128.

- 1 2 Cocker (2008), p.146.

- ↑ Poolman (1972), p.109.

- ↑ Poolman (1972), p.117.

- ↑ Imperial War Museum. "THE ROYAL NAVY DURING THE SECOND WORLD WAR (A 22179)". archive.iwm.org.uk. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

See also Imperial War Museum (2013). "THE ROYAL NAVY DURING THE SECOND WORLD WAR (A 22179)". IWM Collection Search. Retrieved 3 April 2013. - ↑ Poolman (1972), p.143.

- ↑ Poolman (1972), p.142.

- ↑ Speller (2004), p.99.

- ↑ Poolman (1972), p.91.

- ↑ Poolman (1972), p.92.

- ↑ Morison (2002), p.278.

- ↑ Poolman (1972), p.12.

- ↑ Imperial War Museum. "THE ROYAL NAVY DURING THE SECOND WORLD WAR (A 22631)". archive.iwm.org.uk. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

See also Imperial War Museum (2013). "THE ROYAL NAVY DURING THE SECOND WORLD WAR (A 22631)". IWM Collection Search. Retrieved 3 April 2013. - ↑ Imperial War Museum. "THE ROYAL NAVY DURING THE SECOND WORLD WAR (A 23059)". archive.iwm.org.uk. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

See also Imperial War Museum (2013). "THE ROYAL NAVY DURING THE SECOND WORLD WAR (A 23059)". IWM Collection Search. Retrieved 3 April 2013. - ↑ Thomas (2007), p.62.

- ↑ "Altamaha". Naval Historical Center. Retrieved 12 October 2010.

- ↑ "Ships". Fleet Air Arm Officers Association. Retrieved 7 October 2010.

References

- Cocker, Maurice (2008). Aircraft-Carrying Ships of the Royal Navy. Stroud, Gloucestershire: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-4633-2.

- Friedman, Norman (1988). British Carrier Aviation: the Evolution of the Ships and their Aircraft. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-0-85177-488-6.

- Morison, Samuel (2002). History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-07062-4.

- Poolman, Kenneth (1972). Escort Carrier 1941–1945. London: Ian Allen. ISBN 0-7110-0273-8.

- Speller, Ian (2004). The Royal Navy and Maritime Power in the Twentieth Century. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-35004-4.

- Thomas, Andrew (2007). Royal Navy Aces of World War 2. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84603-178-6.