Baal Shem

Baal Shem (Hebrew: בַּעַל שֵׁם, pl. Baalei Shem) in Hebrew meaning "Master of the Name", refers to a historical Jewish occupation of certain kabbalistic rabbis with knowledge of using names of God in Judaism for practical kabbalah healing, miracles,[1] exorcism[2] and blessing.

History

The unofficial title was given by others who recognised or benefited from the Baal Shem's ability to perform wondrous deeds, and emerged in the Middle Ages, continuing until the early-Modern era. Baal Shem were seen as miracle workers who could bring about cures and healing, as well having mystical powers to foresee or interpret events and personalities. They were considered to have a "direct line" to Heaven evoking God's mercies and compassion on suffering human beings. In Jewish society, the practical theurgic role of Baalei Shem among the common folk was a mystical institution, contrasted with the more theosophical and ecstatic Kabbalistic study circles, who were isolated from the populance. The Baal Shem, the communal Maggid preacher, and the Mokhiakh (מוֹכִיחַ/preacher) of penitence were seen as lower level unofficial Jewish intelligentsia, below contract Rabbis and study Kabbalists.[2]

The activity of Baalei Shem among the community, as well as the influence of kabbalistic ideas, contributed to the popular belief in Tzadikim Nistarim (Concealed Righteous). Hasidic tradition records Elijah Ba'al Shem of Chelm in the 16th century, founding a "Nistarim" mystical brotherhood to offer physical and spiritual encouragement to the Jewish populace, making him the first Baal Shem, and from which movement Hasidism later emerged.[3]

Hasidism

A few people received the title of Baal Shem among Eastern and Central European Ashkenazi Jewry. The name is most well known in reference to the founder of Hasidic Judaism, the Baal Shem Tov (Besht – "Master of the Good Name") – Israel ben Eliezer (1698–1760) in Ukraine. However, this is misleading. The Baal Shem Tov started public life as a traditional Baal Shem, but with his teachings of Hasidism, introduced a new way into mystical thought and practice. His role is distinguished from other, predominantly earlier, Baal Shem by the addition of Tov – Good to his title. Hasidism popularised esoteric Kabbalah into a social mysticism movement. The new mystical role of the Hasidic Tzadik leader replaced Baal Shem activity among the populace, combining Kabbalist and Maggid, and replacing practical kabbalah with the Tzadik's divine intercession. The 1814–15 Praises of the Besht sets the Baal Shem Tov's teaching circle against his remaining occupation as travelling Baal Shem.[4][5]

Baal Shem practice and Kabbalah

| Part of a series on | |||||||||||||||||||

| Kabbalah | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||

|

Concepts |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Role

|

|||||||||||||||||||

The "Name" referred to in "Master of the Name" is the most holy Four-Letter Name of God or Tetragrammaton. In Jewish tradition, this Name was pronounced only by the High Priest on Yom Kippur. With the destruction of the Second Temple by the Romans in the year 70 CE, the true pronunciation was presumably lost. (Jews today do not pronounce the Name out loud, and substitute another Hebrew word, usually Adonai, in prayers and texts.) In some accounts, a Baal Shem was believed to have re-discovered the true pronunciation, perhaps during deep meditation, and could use it in magical ways to work miracles. Some stories say he pronounced it out loud, others say he visualized the Name in his mind. He also used the names of angels in this way.

Amulets and Practical Kabbalah

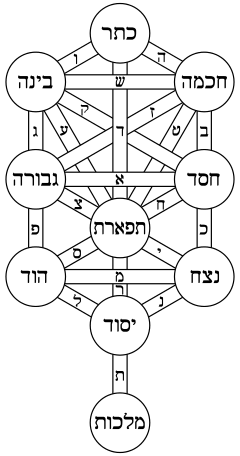

There are two differentiated streams in Kabbalah, that leading Kabbalists separated over concerns of illegitimate use of Practical Kabbalah:[6]

- Kabbalah Iyunit, "Contemplative Kabbalah" (Theosophical-Meditative)

- Kabbalah Ma'asit, "Practical Kabbalah" (Seeking to alter Nature in holiness)

The leading Kabbalist Isaac Luria (1534–1572) forbade people of his time to use Practical Kabbalah. As the Temple in Jerusalem is not standing, and no one possesses the ashes of the Red Heifer, people are unable to become pure. Without these things, he said, Practical Kabbalah is very damaging. Yitzchak Ginsburgh describes the connection of Jewish amulets to Practical Kabbalah:

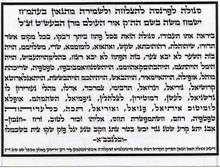

Amulets are on the border between Practical Kabbalah and an external manifestation of Kabbalah, such as name calculation. There is a source for amulets in the Torah. When a great sage writes Holy Names, without pronouncing them, on parchment and puts it into a container which is worn by the recipient, it can possess healing and spiritual powers. At the beginning of the Baal Shem Tov's life, since he was a healer, he used amulets. Sometimes the amulet works because of the faith of the recipient in the spiritual power of the amulet. At the end of his life, the Baal Shem Tov never wrote the Names of God, only his own signature, Yisrael ben Sara or Yisrael ben Eliezer. This was the ultimate amulet given by the Ba'al Shem Tov.

The Sages teach us that whoever receives a coin from the hands of Job (a tzadik) receives a blessing. This is the source in the Talmud that receiving a coin from a great tzaddik brings with it a blessing. Thus we see that there are amulets that are permissible. The determining factor is the righteousness and intentions of the person giving the amulet.[7]

Recorded Baalei Shem

A rare group of people have been recorded as holding the title of Baal Shem. The first recorded person to receive the title was Eliyahu of Chelm.[1]

Other Baalei Shem (besides the above) include:

- Elchanan, rabbi in Vienna, 17th century[1]

- Elijah Loans (1555-1636)[1][8]

- Eliyahu Baal Shem of Worms[9]

- Hayyim Samuel Jacob Falk of London (1708-1782)[1]

- Gedaliah of Worms, an eminent Talmudist (died between 1622 and 1624)[1]

- Joel (I) b. Isaac Heilprin of Zamość ([ˈzamɔɕt͡ɕ]; Yiddish: Zamoshtsh), student of Eliyahu Baal Shem of Worms and Rabbi Yoel Sirkis, mid 17h century[1][8][10][11]

- Joel (II) b. Uri Heilprin, grandson of Joel (I), beginning of the 18th century[1][12]

- Selig of Lublin, beginning of the 18th century[1]

- Wolf, lived in Poland, beginning of the 18th century[1]

- Sekl Loeb Wormser (1768-1846), the Baal Shem of Michelstadt, still known in Germany under that name[1][13]

- Adam Baal Shem, student of Yoel Baal Shem (I) of Zamość, teacher or colleague of Rabbi Israel Baal Shem Tov

- Binyamin Binush, author of Amtahat Binyamin[14] (published 1716[15])

- Hirsch Fraenkel (end of 17th century and 1st half of 18th century), rabbi in several German communities including Heidelberg and Ansbach[16]

- Yosef of Jerusalem (visited Pinchas Kantzelnbogen in 1720)[17]

- Naphtali Cohen of Poznań[16]

Hasidic replacement of the Baal Shem

Contemporary legacies

The name "Baal Shem" mainly survives in Jewish surnames of people descending from Ba'ale Shem such as Balshem, Balshemnik and Bolshemennikov.

In recent years, some new age Jewish groups have revived the term as referring to the Jewish equivalent of a shaman or folk healer.

See also

- Chassidei Ashkenaz

- Kabbalah

- Practical Kabbalah

- Meditative Kabbalah

- Hasidic Judaism

- Tzadik

- Tzadikim Nistarim

- Maggid

- Baal Shem Tov

- Pneumatics

References

- Some Notes on the Social Background of Early Hasidism and A Circle of Pneumatics in Pre-Hasidism, in Studies in East European Jewish Mysticism and Hasidism, Joseph Weiss, Littman Library pub.

- Lubavitcher Rabbi's Memoirs: Tracing the Origins of the Chasidic Movement, 3 Volumes, Joseph Isaac Schneersohn, translated by Nissan Mindel, Kehot publications. Traces the early Nistarim brotherhood circle of Baal Shem and associates, in which the Baal Shem Tov became a member, and from which Hasidism emerged

- Der Ba’al Schem von Michelstadt. Ein deutsch-jüdisches Heiligenleben zwischen Legende und Wirklichkeit. Mit einem Neuabdruck der Legenden aus der Hand von Judaeus und Arthur Kahn, Karl E. Grözinger, Frankfurt/New York (Campus) 2010. A latter-day Baal Shem

Sources

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Kohler, Kaufmann; Ginzberg, Louis (1906). "Ba'al Shem". JewishEncyclopedia.com. Retrieved October 28, 2014.

- 1 2 Studies in East European Jewish Mysticism and Hasidism, Joseph Weiss, Littman Library: chapter 1 "Some Notes on the Social Background of Early Hasidism", chapter 2 "A Circle of Pneumatics in Pre-Hasidism"

- ↑ Lubavitcher Rabbi's Memoires, Joseph Isaac Schneersohn, Kehot publications, 3 volumes

- ↑ Life Stories: Shivhei Ha-Besht by Moshe Rosman, hasidicstories.com

- ↑ Two recent studies of the historical Baal Shem Tov: Founder of Hasidism: A Quest for the Historical Ba'al Shem Tov, Moshe Rosman, California University 1996; The Besht: Magician, Mystic, and Leader, Immanuel Etkes, Brandeis 2004

- ↑ What is Practical Kabbalah? from www.inner.org

- ↑ Are Amulets Considered Practical Kabbalah? Do they work? from www.inner.org

- 1 2 Etkes, Immanuel. The Besht: Magician, Mystic, and Leader. p. 25. Retrieved Nov 5, 2014.

- ↑ Schneersohn, Yosef Y. (2004) [First published 1960]. Lubavitcher Rabbi's Memoirs (PDF). 2. English Rendition by Nissan Mindel (Revised ed.). Brooklyn, New York: Kehot Publication Society. p. 32. ISBN 0-8266-0622-9. Retrieved Aug 17, 2016.

- ↑ Schneersohn, Yosef Y. (2004) [First published 1960]. "The Baal Shem of Zamoshtch". Lubavitcher Rabbi's Memoirs (PDF). 2. English Rendition by Nissan Mindel (Revised ed.). Brooklyn, New York: Kehot Publication Society. p. 89. ISBN 0-8266-0622-9. Retrieved Nov 18, 2014.

- ↑ "Rabbi Yoel Baal Shem, Charms And Amulets". bibliopolis.com. 2014. Retrieved Nov 18, 2014.

- ↑ Etkes. The Besht: Magician, Mystic, and Leader. p. 33. Retrieved Nov 5, 2014.

- ↑ Etkes. The Besht: Magician, Mystic, and Leader. p. 27. Retrieved Mar 26, 2015.

- ↑ Etkes. The Besht: Magician, Mystic, and Leader. pp. 17, 27. Retrieved Mar 26, 2015.

- ↑ Amtahat Binyamin אמתחת בנימן (in Hebrew). Retrieved Mar 24, 2015.

- 1 2 Etkes. The Besht: Magician, Mystic, and Leader. p. 26. Retrieved Mar 26, 2015.

- ↑ Etkes. The Besht: Magician, Mystic, and Leader. pp. 18, 291. Retrieved Mar 25, 2015;

Kantzelnbogen, Pinchas. Yesh Manchilin יש מנחילין (in Hebrew). Jerusalem. p. 96. OCLC 232936737. Retrieved Mar 25, 2015.

External links

- Baal Shem entry in the online 1906 Jewish Encyclopedia

- Historical analysis of Shivhei HaBesht by Moshe Rosman; the Baal Shem Tov's occupation as Baal Shem vs mystical teacher