Bassel al-Assad

| Bassel al-Assad باسل الأسد | |

|---|---|

|

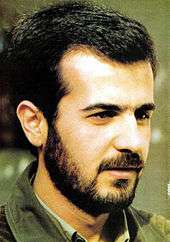

Bassel al-Assad, c. 1992 | |

| Birth name | Bassel al-Assad |

| Nickname(s) | The Golden Knight |

| Born |

23 March 1962 Damascus, Syria |

| Died |

21 January 1994 (aged 31) Damascus, Syria |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/branch | Syrian Arab Army |

| Years of service | 1983–1994 |

| Rank |

|

| Unit |

2nd Special Forces Regiment, 14th Airborne Division Republican Guard |

| Commands held |

42nd Special Forces Regiment 12th Armoured Battalion, Syrian Arab Republican Guard. |

| Awards |

Hero of the Republic Order of Salahaddin |

Bassel al-Assad (Arabic: باسل الأسد, Bāssel al Assad; 23 March 1962 – 21 January 1994) was a Syrian engineer, colonel and politician who was the eldest son of former President of Syria Hafez al-Assad and the older brother of Bashar al-Assad. It was widely expected that he would succeed his father as President of Syria until he died in a car accident in 1994.

Early life and education

Bassel al-Assad was born on 23 March 1962.[1] He was trained as a civil engineer, and he held a PhD in military sciences.[2][3]

We saw father at home but he was so busy that three days could go by without us exchanging a word with him. We never had breakfast or dinner together, and I don't remember ever having lunch together as a family, or maybe we only did once or twice when state affairs were involved. As a family, we used to spend a day or two in Lattakia in the summer, but then too he used to work in the office and we didn't get to see much of him.

Career and succession

Trained in parachuting, he was commissioned in the Special Forces and later switched to the armoured corps after training in the Soviet Military Academies.[3] He rapidly progressed through the ranks, becoming a major and then commander of a brigade in the Republican Guard.[1][5]

After his father recovered from a serious illness in 1984, Bassel began to accompany him and he emerged on the national scene in 1987, when he won several equestrian medals at a regional tournament.[6][5] The Ba'ath Party press in Syria eulogised him as the "Golden Knight" because of his prowess on horseback.[7] He also had a reputation for his interest in fast cars, and his friends described him as charismatic and commanding.[8][9] Assad was soon appointed Head of Presidential Security.[10][11] In addition, he launched the Syrian Computer Society in 1989, which was later headed by Bashar.[12]

Originally Assad's uncle, Rifaat al-Assad, was Hafez's chosen successor but Rifaat attempted to usurp Hafez while he was in a coma in 1984, which led to Rifaat's exile.[3] Following the incident, Bassel was groomed to succeed his father.[13][14] Hafez's efforts intensified to make Bassel the next President of Syria in the early 1990s;[3] after Hafez's election victory in 1991, the President was publicly referred to as "Abu Basil" (Father of Bassel).[15] Assad was also being introduced to European and Arab leaders; he was a close friend of the children of King Hussein of Jordan and had been also introduced to King Fahd of Saudi Arabia.[7]

Assad had a significant role in Lebanese affairs, and was known to Lebanese leaders of all sects.[16] He organised a highly publicised anti-corruption campaign within the government and frequently appeared in full military uniform at official receptions to signal the government's commitment to the armed forces.[8]

Personal life

Bassel is said to have spoken French and Russian fluently.[7] According to leaked United States diplomatic cables, he had a relationship with a Lebanese woman who later married Lebanese journalist and deputy Gebran Tueni.[17]

Death and burial

On 21 January 1994, while he was driving his Mercedes at a high speed through fog to Damascus International Airport for a flight to Germany in the early hours of the morning,[18][19] Bassel collided with a motorway roundabout without wearing a seatbelt, and died instantly.[8][20] Hafez Makhlouf was with him and was hospitalized with injuries after the accident, and a chauffeur in the back seat was unhurt.[20][8]

Assad's body was taken to Al Assad University Hospital and then buried in Qardaha, where his father's body was also later buried.[18][21]

Aftermath

After his death, shops, schools and public offices in Syria closed for three days, and luxury hotels suspended the sale of alcohol in respect.[5] He was elevated by the state into "the martyr of the country, the martyr of the nation and the symbol for its youth".[5]

Numerous squares and streets were named after him. The new international swimming complex, various hospitals, sporting clubs and a military academy were named after him. The international airport in Latakia was named after him, Bassel Al-Assad International Airport. His statue is found in several Syrian cities, and even after his death, he is often pictured on billboards with his father and brother.[5]

Consequences

Bassel Assad's death led to his lesser-known brother, Bashar al-Assad, who was then undertaking postgraduate training in ophthalmology in London, to assume the mantle of president-in-waiting. Bashar became President following the death of his father, on 10 June 2000.[22] Bassel Assad's posters and his name were also used to secure a smooth transition after Hafez Assad through the slogan "Basil, the Example: Bashar, the Future."[23]

References

- 1 2 Zisser, Eyal (September 1995). "The Succession Struggle in Damascus". Middle East Forum. 2 (3): 57–64. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

- ↑ "Assad son dies in car accident". Rome News Tribune. 21 June 1994. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 Ghadbian, Najib (Autumn 2001). "The New Asad: Dynamics of Continuity and Change in Syria" (PDF). Middle East Journal. 55 (4). Retrieved 19 August 2013.

- ↑ "Mid-East Realities". Middle East. 11 June 2000. Retrieved 9 March 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Sipress, Alan (8 November 1996). "Syria Creates Cult Around Its President's Dead Son Bassel Assad". Inquirer. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

- ↑ Kathy A. Zahler (1 August 2009). The Assads' Syria. Twenty-First Century Books. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-8225-9095-8. Retrieved 12 March 2010.

- 1 2 3 Fisk, Robert (22 January 1994). "Syria mourns death of a 'golden son'". The Independent. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 Schmidt, William E. (22 January 1994). "Assad's Son Killed in Auto Crash". New York Times. Retrieved 27 August 2013.

- ↑ Bennet, James (10 July 2005). "The Enigma of Damascus" (PDF). The New York Times. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- ↑ Boustany, Nora (22 January 1994). "Car crash kills Assad's son". The Daily Gazette. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- ↑ Edwards, Alex (July–August 2012). "Understanding Dictators" (PDF). The Majalla. 1574: 32–37. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ↑ Alterman, Jon B. (1998). "New Media New Politics?" (PDF). The Washington Institute. 48. Retrieved 7 April 2013.

- ↑ Brownlee, Jason (Fall 2007). "The Heir Apparency of Gamal Mubarak" (PDF). Arab Studies Journal: 36–56. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- ↑ Hemmer, Christopher (n.d.). Syria Under Bashar Asad: Clinging To His Roots? (PDF). CPC.

- ↑ Cook, Steven A. (December 1996). "On the Road: In Asad's Damascus". Middle East Quarterly: 39–43. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- ↑ "Asad insider sees Bashar coming to help, wants to sell US airplanes". Wikileaks. 19 December 1994. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- ↑ "Daily "An Nahar" reeling from publisher's assassination, in-house feuding". Wikileaks. 2 February 2006. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- 1 2 Bell, Don (November 2009). "Shadowland". National Geographic. Retrieved 9 March 2013.

- ↑ "Basil Assad killed by his brother and father s". The Press Courier. 21 January 1994. Retrieved 27 August 2013.

- 1 2 Sipress, Alan (22 January 1994). "Assad's Son is Killed in a Car". Inquirer. Retrieved 27 August 2013.

- ↑ "Hafez Al Assad passes away". Ain Al Yaqeen. 16 June 2000. Archived from the original on 2 May 2014. Retrieved 9 March 2013.

- ↑ Zisser, Eyal (June 2006). "What does the future hold for Syria?" (PDF). MERIA. 10 (2). Retrieved 14 July 2012.

- ↑ "Nepotism, cronyism, and weakness in Arabdom". MER. 7 September 1998. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

External links

- The death of Bassel al Assad BBC World Service Witness episode