Bath (UK Parliament constituency)

| Bath | |

|---|---|

|

County constituency for the House of Commons | |

|

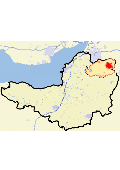

Constituency location within Bath and North East Somerset, Somerset | |

|

Location of Somerset within England. | |

| County | Somerset |

| Population | 88,859 (2011 census)[1] |

| Electorate | 66,690 (December 2010)[2] |

| Current constituency | |

| Created | 1295 |

| Member of parliament | Ben Howlett (Conservative) |

| Number of members |

Two (1295–1918) One (1918–present) |

| Overlaps | |

| European Parliament constituency | South West England |

Bath is a constituency[n 1] in the House of Commons of the Parliament of the United Kingdom[n 2] represented by Ben Howlett of the Conservative Party.

Perhaps its best-known representatives have been the two with international profiles: William Pitt the Elder (Prime Minister 1766–1768) and Chris Patten.[n 3]

History

Bath is an ancient constituency which has been constantly represented in Parliament since boroughs were first summoned to send members in the 13th century.

The unreformed constituency (before 1832)

Bath was one of the cities summoned to send members in 1295 and represented ever since, although Parliaments in early years were sporadic. Like almost all English constituencies before the Great Reform Act of 1832, it originally returned two members to each Parliament.

The precise way in which its MPs were chosen in medieval times is unknown. It is recorded that "election was by the Mayor and three citizens being sent from thence to the county court who in the name of the whole community, and by the assent of the community, returned their representatives"; but what form the "assent of the community" took is unrecorded, even assuming it was not a complete dead letter. By the 17th century elections had become more competitive, and the means of election in Bath had been formalised to a franchise restricted to the Mayor, Aldermen and members of the Common Council (the City Corporation), a total of thirty voters. The freemen of the city challenged this state of affairs in 1661 and again in 1705 claiming the right to vote and petitioning against the election of the candidates chosen by the corporation, but on both occasions the House of Commons, which at the time was still the final arbiter of such disputes, decided against them. The Commons resolution of 27 January 1708, "That the right of election of citizens to serve in Parliament for this city is in the mayor, aldermen and common-council only", settled the matter until 1832.

Bath was the biggest of the English boroughs where the right to vote was restricted to the corporation (at the time of the 1801 census it was one of the ten largest towns or cities in England by population), and almost unique in that the voters generally exercised their powers responsibly and independently. As was the case elsewhere, the Common Council was not popularly elected, all vacancies being filled by co-option by the remaining members, so that once a united interest gained majority control it was easy to retain it. Most corporation boroughs quickly became pocket boroughs in this way, the nomination of their MPs being entirely under the influence of a patron who may have given some large benefaction to the area or simply used bribery to ensure only supporters or croneys became members of the corporation. But in Bath, the Common Council retained its independence in most periods and took pride in electing suitable MPs who either had strong local connections or a national reputation. Nor was there any suggestion of bribery or other corruption, prolific in other "independent" constituencies. Pitt the Elder wrote to the corporation in 1761, on the occasion of his re-election as Bath's MP, to pay tribute to "a city ranked among the most ancient and most considerable in the kingdom, and justly famed for its integrity, independence, and zeal for the public good".

But even in Bath the limited electorate who voted for the MP in question expected that MP to work to procure favours for their constituents and enterprises to a degree that would be considered utterly corrupt today. By exercising efforts successfully in this direction, MPs could in return expect a degree of control over the voters that differed little from patronage in pocket boroughs except that its duration was limited. Thus the lawyer Robert Henley, MP from 1747 and Recorder of Bath from 1751, seems to have been assumed to have had control over both seats while he remained Bath's MP and immediately after; yet when he was transferred to the House of Lords, Pitt replaced him on the understanding of being independently chosen. Pitt himself then acquired similar influence: the Council vetoed Viscount Ligonier's suggestion that he should be succeeded by his nephew when he was elevated the Lords in 1763, but instead allowed Pitt to nominate a candidate to be his new colleague, and voted overwhelmingly for him when he was opposed by a local man. But Pitt's influence also waned when he fell out with the Council over the Treaty of Paris.

In the final years before the Reform Act, however, local magnates exerted more control-like influence in Bath. Oldfield, writing early in the 19th century, stated that at that time the Marquess of Bath nominated one member and John Palmer the other; both were former MPs for the City (the Marquess having sat under the title Viscount Weymouth), but neither was still in the Commons – each had a family member sitting in their stead as MP for Bath. Palmer had succeeded as MP Earl Camden[n 4] who held one of the nominations before 1802. At the time of the Reform Act, the Marquess of Bath was still being listed as influencing one of the seats, though the second was considered independent once more.

The reformed constituency (1832–1918)

The Great Reform Act opened up the franchise to all resident (male) householders whose houses were valued at least £10 a year and imposed uniform voting provisions for boroughs. Reflecting not just the city's medium size but its general property values, this multiplied Bath's electorate by a factor of almost 100[n 5], and created a competitive and generally marginal constituency which swung between Whig and Conservative control. The constituency boundaries were also slightly extended, but only to take in those areas where the city proper had filled. Bath's most notable MP during this period was probably the Conservative social reformer Lord Ashley, better remembered under his eventual title of 7th Earl of Shaftesbury for the Factory Acts, the first of which came into effect while he was MP for Bath.

The franchise was further reformed in 1867 and 1885 with only minor boundary changes. Bath was lucky to retain double-member representation in the 1885 reforms – its electorate of under 7,000 was near the lower limit, a situation that lasted until 1918 reforms. The continued Liberal strength was unusual for a prosperous and predominantly middle-class town, and the seats could until 1918 not be considered safe for the Conservatives.

The modern single-member constituency (since 1918)

Bath's representation was reduced to a single member in 1918. The Conservatives held the seat continuously until 1992 except in the 1923 Parliament, and until World War II generally won comfortably – Liberals retained strength so that the non-Conservative vote was split and Labour could not rise above third place until the landslide of 1945, when the Conservative James Pitman achieved a very marginal majority. From 1945 to 1975 Bath Labour presented the main challengers came within 800 votes of taking the seat in 1966.

The Liberal revival in the 1970s saw the two more left-wing parties swap places, helped by the adoption of a nationally known candidate, Christopher Mayhew who had defected from the Labour Party. The formation of the SDP–Liberal Alliance made Bath a realistic target. The SDP came 1500 votes from winning in 1987 under Malcolm Dean. In 1992, Conservative Chris Patten was ousted by Liberal Democrat Don Foster in a narrow defeat widely blamed on Patten's strategising, campaign leading and communicating as Conservative Party chairman rather than canvassing his own constituents. At each election since 1992 a different [Conservative candidate has taken second place.

The boundary changes implemented in 1997 took Bathampton, Batheaston, Bathford, Charlcombe and Freshford from the Wansdyke district, containing about 7,000 voters – these were given elsewhere in 2010. Nominally this had slightly higher tendency to prefer a Conservative candidate but, the national government suffering from sleaze, in 1997 Don Foster more than doubled his almost 4,000 vote majority to over 9,000 votes. After winning two intervening elections, in 2010 Foster achieved his highest majority to date of 11,883 votes. This result followed the trend in the south-west led by the election performance of Nick Clegg and reflects a loss of the villages mentioned.

Trivia

Bath is one of only two UK Parliament constituencies to be surrounded by another constituency. Bath is entirely surrounded by the North East Somerset constituency. The other constituency, York Central, is entirely surrounded by York Outer.

Boundaries

Current boundaries

Following the review of the constituencies in the former county of Avon carried out by the Boundary Commission for England, as of the 2010 general election the constituency covers only the city of Bath, and none of the surrounding rural area. Between 1997 and 2010, it also included some outlying villages such as Southstoke and Freshford now in the North East Somerset constituency. The changes in 2010 also resulted in Bath becoming a borough constituency, instead of a county constituency as it was before.

The constituency's electoral wards are:[n 6]

- Abbey, Bathwick, Combe Down, Kingsmead, Lambridge, Lansdown, Lyncombe, Bath, Newbridge, Odd Down, Oldfield, Southdown, Twerton, Walcot, Westmoreland, Weston and Widcombe.

Historic boundaries

- Before 1832: The parishes of St James (Bath), St Peter and St Paul (Bath), St Michael (Bath), and part of the parish of Walcot.

- 1832–1867: As above, plus the parishes of Bathwick and Lyncombe & Widcombe, and a further part of the parish of Walcot.

- 1867–1918: As above, plus part of the parish of Twerton.

- 1918–1983: The county borough of Bath

- 1983–1997: The City of Bath

- 1997–2010: The City of Bath, and the Bathampton, Batheaston, Bathford, Charlcombe and Freshford wards of the District of Wansdyke.

Members of Parliament

The current Member of Parliament is Ben Howlett of the Conservative Party.

William Pitt the Elder was briefly Prime Minister from 30 July 1766 while a Bath MP ending when on 4 August 1766 he was raised to the peerage as Earl of Chatham.

Members of Parliament 1295–1640

- Constituency created (1295)

Members of Parliament 1640–1918

Members of Parliament since 1918

Elections

Elections in the 2010s

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ± | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservative | Ben Howlett [14] | 17,833 | 37.8 | +6.4 | |

| Liberal Democrat | Steve Bradley [15] | 14,000 | 29.7 | −26.9 | |

| Labour | Ollie Middleton [16][17] | 6,216 | 13.2 | +6.3 | |

| Green | Dominic Tristram [18] | 5,634 | 11.9 | +9.6 | |

| UKIP | Julian Deverell [19] | 2,922 | 6.2 | +4.3 | |

| Independent | Loraine Morgan-Brinkhurst [20][21] | 499 | 1.1 | +1.1 | |

| English Democrat | Jenny Knight | 63 | 0.1 | +0.1 | |

| Majority | 3,833 | 8.1 | −7 | ||

| Turnout | 47,167 | 77.5 | 5.7 | ||

| Conservative gain from Liberal Democrat | Swing | +16.7 | |||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ± | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liberal Democrat | Don Foster | 26,651 | 56.6 | +11.2 | |

| Conservative | Fabian Richter | 14,768 | 31.4 | −0.5 | |

| Labour | Hattie Ajderian | 3,251 | 6.9 | −7.5 | |

| Green | Eric Lucas | 1,120 | 2.4 | −3.6 | |

| UKIP | Ernie Warrender | 890 | 1.9 | +0.2 | |

| Christian | Steve Hewett | 250 | 0.5 | N/A | |

| Independent | A.N.ON | 69 | 0.1 | N/A | |

| Independent | Sean Geddis | 56 | 0.1 | N/A | |

| All The South Party | Robert Craig | 31 | 0.1 | N/A | |

| Majority | 11,883 | 25.2 | +15.1 | ||

| Turnout | 47,086 | 71.8 | +2.7 | ||

| Liberal Democrat hold | Swing | +5.8 | |||

Elections in the 2000s

The 2005 general election saw two more candidates stand than in 2001, both of whom were independent. All parties apart from the Liberal Democrats ran different candidates.

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ± | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liberal Democrat | Don Foster | 20,101 | 43.9 | −6.6 | |

| Conservative | Sian Dawson | 15,463 | 33.7 | +4.6 | |

| Labour | Harriet Ajderian | 6,773 | 14.8 | −0.9 | |

| Green | Eric Lucas | 2,494 | 5.4 | +2.2 | |

| UKIP | Richard Crowder | 770 | 1.7 | +0.2 | |

| Independent | Patrick Cobbe | 177 | 0.4 | N/A | |

| Independent | Graham Walker | 58 | 0.1 | N/A | |

| Majority | 4,638 | 10.1 | −11.3 | ||

| Turnout | 45,836 | 68.6 | +3.7 | ||

| Liberal Democrat hold | Swing | −5.6 | |||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ± | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liberal Democrat | Don Foster | 23,372 | 50.5 | +2.0 | |

| Conservative | Ashley Fox | 13,478 | 29.1 | −2.1 | |

| Labour | Marilyn Hawkings | 7,269 | 15.7 | −0.7 | |

| Green | Michael Boulton | 1,469 | 3.2 | +2.1 | |

| UKIP | Andrew Tettenborn | 708 | 1.5 | +0.9 | |

| Majority | 9,894 | 21.4 | +4.1 | ||

| Turnout | 46,296 | 64.9 | −11.3 | ||

| Liberal Democrat hold | Swing | ||||

Elections in the 1990s

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ± | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liberal Democrat | Don Foster | 26,169 | 48.5 | −0.4 | |

| Conservative | Alison McNair | 16,850 | 31.2 | −9.4 | |

| Labour | Tim Bush | 8,828 | 16.4 | +8.6 | |

| Referendum | Tony Cook | 1,192 | 2.2 | N/A | |

| Green | Richard Scrase | 580 | 1.1 | +0.3 | |

| UKIP | Peter Sandell | 315 | 0.6 | N/A | |

| Natural Law | Nicholas Pullen | 55 | 0.1 | N/A | |

| Majority | 9,319 | 17.3 | +10.2 | ||

| Turnout | 53,989 | 76.2 | −9.3 | ||

| Liberal Democrat hold | Swing | ||||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ± | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liberal Democrat | Don Foster | 25,718 | 48.9 | +6.3 | |

| Conservative | Christopher Francis Patten | 21,950 | 41.8 | −3.6 | |

| Labour | Mrs Pamela Rosemary Richards | 4,102 | 7.8 | −2.8 | |

| Green | Duncan McCanlis | 433 | 0.8 | −0.5 | |

| Liberal | Mrs May Joan Barker | 172 | 0.3 | +0.3 | |

| Anti-Federalist League | Alan Sked | 117 | 0.2 | +0.2 | |

| Independent | John Albert S. Rumming | 79 | 0.2 | +0.2 | |

| Majority | 3,768 | 7.2 | +4.4 | ||

| Turnout | 52,571 | 82.4 | +2.9 | ||

| Liberal Democrat gain from Conservative | Swing | +4.9 | |||

Elections in the 1980s

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ± | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservative | Christopher Francis Patten | 23,515 | 45.4 | ||

| Social Democratic | James Malcolm Dean | 22,103 | 42.7 | ||

| Labour | Jenny Smith | 5,507 | 10.6 | ||

| Green | Derek Wall | 687 | 1.3 | ||

| Majority | 1,412 | 2.7 | |||

| Turnout | 79.4 | ||||

| Conservative hold | Swing | ||||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ± | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservative | Christopher Francis Patten | 22,544 | 47.1 | ||

| Social Democratic | James Malcolm Dean | 17,240 | 36.0 | ||

| Labour | A. J. Pott | 7,259 | 15.2 | ||

| Ecology | D. Grimes | 441 | 0.9 | ||

| Progressive Liberal | R. S. Wandle | 319 | 0.7 | ||

| World Government | Sidney Gilbert Young | 67 | 0.1 | ||

| Majority | 5,304 | 11.1 | |||

| Turnout | 74.4 | ||||

| Conservative hold | Swing | ||||

Elections in the 1970s

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ± | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservative | Christopher Francis Patten | 23,025 | 46.4 | ||

| Liberal | Christopher Paget Mayhew | 13,913 | 28.0 | ||

| Labour | M. Baber | 11,407 | 23.0 | ||

| Ecology | D. Grimes | 1,082 | 2.2 | ||

| National Front | T. Mundy | 206 | 0.4 | ||

| Majority | 9,112 | 18.4 | |||

| Turnout | 78.1 | ||||

| Conservative hold | Swing | ||||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ± | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservative | Sir Edward Joseph Brown | 18,470 | 37.7 | ||

| Liberal | Christopher Paget Mayhew | 16,348 | 33.4 | ||

| Labour | Malcolm Leslie Bishop | 14,011 | 28.6 | ||

| United Democratic | John Vernon Kemp | 150 | 0.3 | ||

| Majority | 2,122 | 4.3 | |||

| Turnout | 78.6 | ||||

| Conservative hold | Swing | ||||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ± | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservative | Sir Edward Joseph Brown | 20,920 | 40.8 | ||

| Liberal | P. Downey | 15,738 | 30.7 | ||

| Labour | Malcolm Leslie Bishop | 14,396 | 27.9 | ||

| Independent Conservative | H. B. de Laterriere | 204 | 0.4 | ||

| World Government | Sidney Gilbert Young | 118 | 0.2 | ||

| Majority | 5,182 | 10.1 | |||

| Turnout | 83.0 | ||||

| Conservative hold | Swing | ||||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ± | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservative | Sir Edward Joseph Brown | 22,344 | 49.0 | ||

| Labour | David Wright Young | 16,493 | 36.1 | ||

| Liberal | Roger H. Crowther | 5,957 | 13.1 | ||

| World Government | Sidney Gilbert Young | 840 | 1.8 | ||

| Majority | 5,851 | 12.8 | |||

| Turnout | 45,634 | 77.1 | |||

| Conservative hold | Swing | ||||

Elections in the 1960s

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ± | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservative | Sir Edward Joseph Brown | 19,344 | 43.0 | ||

| Labour | Frederick S. Moorhouse | 18,544 | 41.2 | ||

| Liberal | Roger H. Crowther | 7,095 | 15.8 | ||

| Majority | 800 | 1.8 | |||

| Turnout | 44,983 | 80.5 | |||

| Conservative hold | Swing | +3.2 | |||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ± | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservative | Sir Edward Joseph Brown | 22,255 | 46.5 | ||

| Labour | Frederick S. Moorhouse | 16,464 | 34.4 | ||

| Liberal | Dr. Brian R. Pamplin | 8,795 | 18.4 | ||

| World Government | Sidney Gilbert Young | 318 | 0.7 | ||

| Majority | 5,791 | 12.1 | |||

| Turnout | 45,832 | 84.2 | |||

| Conservative hold | Swing | ||||

Elections in the 1950s

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ± | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservative | Isaac James Pitman | 24,048 | 50.33 | ||

| Labour | George E Mayer | 17,515 | 36.66 | ||

| Liberal | George Allen | 6,214 | 13.01 | ||

| Majority | 6,533 | 13.67 | |||

| Turnout | 47,777 | 83.60 | |||

| Conservative hold | Swing | ||||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ± | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservative | Isaac James Pitman | 24,489 | 51.94 | ||

| Labour | Thomas W Richardson | 17,646 | 37.43 | ||

| Liberal | Miss Barbara Burwell | 5,011 | 10.63 | ||

| Majority | 6,843 | 14.51 | |||

| Turnout | 47.146 | 82.46 | |||

| Conservative hold | Swing | ||||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ± | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservative | Isaac James Pitman | 27,826 | 55.26 | ||

| Labour | C J Victor Mishcon | 22,530 | 44.74 | ||

| Majority | 5,296 | 10.52 | |||

| Turnout | 85.64 | ||||

| Conservative hold | Swing | ||||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ± | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservative | Isaac James Pitman | 23,070 | 47.16 | ||

| Labour | Hugh Bruce Oliphant Cardew | 19,340 | 39.54 | ||

| Liberal | Philip W. Hopkins | 6,508 | 13.30 | ||

| Majority | 3,730 | 7.63 | |||

| Turnout | 87.28 | ||||

| Conservative hold | Swing | ||||

Elections in the 1940s

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ± | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservative | Isaac James Pitman | 20,196 | 43.6 | ||

| Labour | Lady Dorothy Archibald | 18,120 | 39.2 | ||

| Liberal | Philip W. Hopkins | 7,952 | 17.2 | ||

| Majority | 2,076 | 4.5 | |||

| Conservative hold | Swing | ||||

Election in the 1930s

General Election 1939/40:

Another General Election was required to take place before the end of 1940. The political parties had been making preparations for an election to take place and by the Autumn of 1939, the following candidates had been selected;

- Conservative: Lord Ronaldshay[31]

- Liberal: Philip W. Hopkins[32]

- Labour: George Gilbert Desmond[33]

- A minority of Bath Conservatives, led by the town Mayor, Adrian Hopkins objected to Ronaldshay who had no link with the town. Hopkins was considering running as an Independent.[34] Desmond was under pressure to withdraw in favour of the Liberal candidate fighting on a Popular Front programme.

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ± | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservative | Thomas Loel Evelyn Bulkeley Guinness | 20,670 | 56.6 | -7.4 | |

| Liberal | Sidney Reginald Daniels | 8,650 | 23.7 | +2.4 | |

| Labour | George Gilbert Desmond | 7,185 | 19.7 | +5.0 | |

| Majority | 12,020 | 32.9 | -9.8 | ||

| Turnout | 74.5 | -6.0 | |||

| Conservative hold | Swing | -4.7 | |||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ± | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservative | Thomas Loel Evelyn Bulkeley Guinness | 24,696 | 64.0 | +17.1 | |

| Liberal | Sidney Reginald Daniels | 8,241 | 21.3 | -8.8 | |

| Labour | George Gilbert Desmond | 5,680 | 14.7 | -8.3 | |

| Majority | 16,455 | 42.6 | +25.8 | ||

| Turnout | 80.6 | -0.7 | |||

| Conservative hold | Swing | +12.9 | |||

Election in the 1920s

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ± | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unionist | Hon. Charles William Baillie-Hamilton | 17,845 | 46.9 | +1.8 | |

| Liberal | Sidney Reginald Daniels | 11,485 | 30.1 | +0.8 | |

| Labour | George Gilbert Desmond | 8,769 | 23.0 | -2.7 | |

| Majority | 6,360 | 16.8 | +1.0 | ||

| Turnout | 81.3 | +8.5 | |||

| Unionist hold | Swing | +0.5 | |||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ± | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unionist | Hon. Charles William Baillie-Hamilton | 11,171 | 45.1 | -10.7 | |

| Liberal | Sidney Reginald Daniels | 7,255 | 29.3 | -1.3 | |

| Labour | George Gilbert Desmond | 6,359 | 25.7 | +12.1 | |

| Majority | 3916 | 15.8 | -9.4 | ||

| Turnout | 24,785 | 72.8 | -11.7 | ||

| Unionist hold | Swing | -4.6 | |||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ± | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unionist | Charles Talbot Foxcroft | 16,067 | 55.8 | +7.4 | |

| Liberal | Frank Walter Raffety | 8,800 | 30.6 | -21.0 | |

| Labour | Walter Barton Scobell | 3,914 | 13.6 | +13.6 | |

| Majority | 7,267 | 25.2 | 28.4 | ||

| Turnout | 84.5 | +5.4 | |||

| Unionist gain from Liberal | Swing | +14.2 | |||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ± | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liberal | Frank Walter Raffety | 13,694 | 51.6 | +19.6 | |

| Unionist | Charles Talbot Foxcroft | 12,830 | 48.4 | -1.8 | |

| Majority | 864 | 3.2 | 21.4 | ||

| Turnout | 79.1 | -3.3 | |||

| Liberal gain from Unionist | Swing | +10.7 | |||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ± | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unionist | Charles Talbot Foxcroft | 13,666 | 50.2 | -24.6 | |

| Liberal | Edward Harold Spender | 8,699 | 32.0 | n/a | |

| Labour | Herbert Henry Elvin | 4,849 | 17.8 | -7.4 | |

| Majority | |||||

| Turnout | 82.4 | ||||

| Unionist hold | Swing | ||||

Election in the 1910s

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ± | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unionist | 15,605 | n/a | |||

| Labour | Alfred James Bethell | 5,244 | n/a | ||

| Majority | n/a | ||||

| Turnout | n/a | ||||

| Unionist win | |||||

- endorsed by Coalition Government

General Election 1914/15:

Another General Election was required to take place before the end of 1915. The political parties had been making preparations for an election to take place and by July 1914, the following candidates had been selected;

- Unionist: Sir Charles Hunter, Lord Alexander George Boteville Thynne

- Liberal: Harry Geen,[37] J.C. Meggott[38]

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ± | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservative | Lord Alexander George Boteville Thynne | 3,875 | |||

| Conservative | Sir Charles Roderick Hunter | 3,841 | |||

| Liberal | George Peabody Gooch | 3,631 | |||

| Liberal | George Alexander Hardy | 3,585 | |||

| Majority | |||||

| Turnout | |||||

| Conservative hold | Swing | ||||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ± | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservative | Lord Alexander George Boteville Thynne | 3,961 | |||

| Conservative | Sir Charles Roderick Hunter | 3,889 | |||

| Liberal | Donald Maclean | 3,771 | |||

| Liberal | George Peabody Gooch | 3,757 | |||

| Majority | |||||

| Turnout | |||||

| Conservative gain from Liberal | Swing | ||||

Elections in the 1900s

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ± | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liberal | Donald Maclean | 4,102 | |||

| Liberal | George Peabody Gooch | 4,069 | |||

| Conservative | Lord Alexander George Boteville Thynne | 3,123 | |||

| Conservative | Sir Charles Wyndham Murray | 3,088 | |||

| Majority | 946 | ||||

| Turnout | |||||

| Liberal gain from Conservative | Swing | ||||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ± | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservative | Charles Wyndham Murray | 3,486 | |||

| Liberal Unionist | Rt Hon. Edmond Robert Wodehouse | 3,439 | |||

| Liberal | Donald Maclean | 2,605 | |||

| Liberal | Alpheus Cleophas Morton | 2,549 | |||

| Majority | 834 | ||||

| Turnout | |||||

| Conservative hold | Swing | ||||

See also

Notes and references

- Notes

- ↑ A borough constituency (for the purposes of election expenses and type of returning officer)

- ↑ Previously represented by two MPs in the House of Commons of England

- ↑ Conservative Party chairman 1990–1992 and last Governor of Hong Kong.

- ↑ Formerly known as John Jeffreys Pratt

- ↑ 2,853 voters registered at the first reformed election, in December 1832)

- ↑ These form the City of Bath in Bath and North East Somerset

- References

- ↑ "Bath: Usual Resident Population, 2011". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- ↑ "Electorate Figures – Boundary Commission for England". 2011 Electorate Figures. Boundary Commission for England. 4 March 2011. Archived from the original on 6 November 2010. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 "History of Parliament". History of Parliament Trust. Retrieved 2 November 2011.

- ↑ http://historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1386-1421/member/chapman-william

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "History of Parliament". History of Parliament Trust. Retrieved 2 November 2011.

- ↑ Wroughton, John (2006). Tudor Bath – Life and strife in the little city, 1485–1603. Bath: Lansdown Press. pp. 58–59. ISBN 0-9520249-6-9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "History of Parliament". History of Parliament Trust. Retrieved 2 November 2011.

- 1 2 "Bath". The History of Parliament. The History of Parliament Trust. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- ↑ Popham was also elected for Wiltshire

- ↑ Field Marshal from 1743

- ↑ Created Viscount Ligonier (in the Peerage of Ireland), December 1757

- ↑ Styled Viscount Bayham from May 1786

- ↑ "Election Data 2015". Electoral Calculus. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

- ↑ Bath Conservatives (2 November 2013). "Ben Howlett selected as Conservative Prospective Parliamentary Candidate for Bath". Archived from the original on 4 October 2014. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- ↑ BathNES Liberal Democrats (May 2014). "Bath Lib Dems Select Steve Bradley for 2015". Archived from the original on 19 January 2015. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- ↑ Western Daily Press (3 December 2013). "Bath Labour candidate Ollie Middleton could become youngest-ever MP". Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- ↑ Bath Labour (18 February 2014). "Ollie Middleton selected as Bath Labour PPC". Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- ↑ bath.greenparty.org.uk (11 March 2014). "Dominic Tristram Selected As PPC For Bath". Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- ↑ Bath UKIP (25 February 2014). "Bath UKIP Selects Julian Deverell To Contest Bath Seat In 2015 Generel Election". Archived from the original on 19 January 2015. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- ↑ Jaynes, Anita. "Independent bids to become first female MP for Bath". Excaliber. Retrieved 1 November 2016.

- ↑ Bath Chronicle (29 January 2015). "Councillor Loraine Morgan-Brinkhurst to stand in General Election as independent MP candidate for Bath". Retrieved 30 January 2015.

- ↑ "Election Data 2010". Electoral Calculus. Archived from the original on 26 July 2013. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

- ↑ "BBC – Election 2010 – Bath". BBC News.

- ↑ "Election Data 2005". Electoral Calculus. Archived from the original on 15 October 2011. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- ↑ "Election Data 2001". Electoral Calculus. Archived from the original on 15 October 2011. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- ↑ "Election Data 1997". Electoral Calculus. Archived from the original on 15 October 2011. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- ↑ "Election Data 1992". Electoral Calculus. Archived from the original on 15 October 2011. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- ↑ "Politics Resources". Election 1992. Politics Resources. 9 April 1992. Retrieved 6 December 2010.

- ↑ "Election Data 1987". Electoral Calculus. Archived from the original on 15 October 2011. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- ↑ "Election Data 1983". Electoral Calculus. Archived from the original on 15 October 2011. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- ↑ Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 6 May 1939

- ↑ 8 May 1937, Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette

- ↑ Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 26 February 1938

- ↑ Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 1 April 1939

- 1 2 3 4 British parliamentary election results 1818–1949, Craig, F. W. S.

- ↑ British parliamentary election results 1885–1918, Craig, F.W.S.

- ↑ Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 2 May 1914

- ↑ Taunton Courier, and Western Advertiser, 21 Jan 1914

- 1 2 Debrett's House of Commons & Judicial Bench, 1916

- 1 2 The Liberal Year Book, 1907

- ↑ Debrett's House of Commons & Judicial Bench, 1901

Sources

- "Parliamentary representation". Aspects of Somerset History. Retrieved 26 April 2005.

- "Bath". 2001 election results. Retrieved 26 April 2005.

- "Bath election history". Guardian Unlimited Politics. London. Archived from the original on 8 May 2005. Retrieved 26 April 2005.

- "Boundary Commission for England – Bath". Boundary changes. Archived from the original on 12 March 2005. Retrieved 3 July 2005.

- "Constituencies in the unreformed House". Constituency start dates. Retrieved 3 July 2005.

- The BBC/ITN Guide to the New Parliamentary Constituencies (Chichester: Parliamentary Research Services, 1983)

- Robert Beatson, A Chronological Register of Both Houses of Parliament (London: Longman, Hurst, Res & Orme, 1807)

- D Brunton & D H Pennington, Members of the Long Parliament (London: George Allen & Unwin, 1954)

- Cobbett's Parliamentary history of England, from the Norman Conquest in 1066 to the year 1803 (London: Thomas Hansard, 1808)

- The Constitutional Year Book for 1913 (London: National Union of Conservative and Unionist Associations, 1913)

- F W S Craig, British Parliamentary Election Results 1832–1885 (2nd edition, Aldershot: Parliamentary Research Services, 1989)

- F W S Craig, British Parliamentary Election Results 1918–1949 (Glasgow: Political Reference Publications, 1969)

- Lewis Namier & John Brooke, The History of Parliament: The House of Commons 1754–1790 (London: HMSO, 1964)

- T. H. B. Oldfield, The Representative History of Great Britain and Ireland (London: Baldwin, Cradock & Joy, 1816)

- Henry Pelling, Social Geography of British Elections 1885–1910 (London: Macmillan, 1967)

- J Holladay Philbin, Parliamentary Representation 1832 – England and Wales (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1965)

- Edward Porritt and Annie G Porritt, The Unreformed House of Commons (Cambridge University Press, 1903)

- Colin Rallings & Michael Thrasher (eds), Media Guide to the New Parliamentary Constituencies (London: BBC/ITN/PA News/Sky, 1995)

- Robert Walcott, English Politics in the Early Eighteenth Century (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1956)

- Robert Waller, The Almanac of British Politics (1st edition, London: Croom Helm, 1983)

- Frederic A Youngs, jr, Guide to the Local Administrative Units of England, Vol I (London: Royal Historical Society, 1979)

External links

| Parliament of the United Kingdom | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by vacant. Last was Buckingham in 1765 |

Constituency represented by the Prime Minister 1766 |

Succeeded by vacant. Next was Banbury in 1770 |

Coordinates: 51°22′51″N 2°21′37″W / 51.3809°N 2.3603°W