Batting average

Batting average is a statistic in cricket, baseball, and softball that measures the performance of batsmen in cricket and batters in baseball. The development of the baseball statistic was influenced by the cricket statistic.[1]

Cricket

In cricket, a player's batting average is the total number of runs they have scored divided by the number of times they have been out. Since the number of runs a player scores and how often they get out are primarily measures of their own playing ability, and largely independent of their team mates, batting average is a good metric for an individual player's skill as a batsman. The number is also simple to interpret intuitively. If all the batsman's innings were completed (i.e. they were out every innings), this is the average number of runs they score per innings. If they did not complete all their innings (i.e. some innings they finished not out), this number is an estimate of the unknown average number of runs they score per innings. Batting average has been used to gauge cricket players' relative skills since the 18th century.

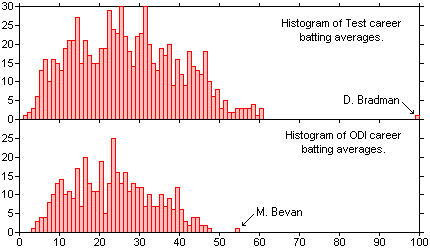

Most players have career batting averages in the range of 20 to 40. This is also the desirable range for wicket-keepers, though some fall short and make up for it with keeping skill. Until a substantial increase in scores in the 21st century due to improved bats and smaller grounds among other factors, players who sustained an average above 50 through a career were considered exceptional, and before the development of the heavy roller in the 1870s an average of 25 was considered very good.[2]

- All-rounders who are more prominent bowlers than batsmen typically average something between 20 and 30.

- 15 and under is typical for specialist bowlers.

- A small number of "rabbits" have averaged less than 5 for a complete career, though a player with such an average is a liability unless an exceptional bowler as Alf Valentine or B. S. Chandrasekhar were.

Career records for batting average are usually subject to a minimum qualification of 20 innings played or completed, in order to exclude batsmen who have not played enough games for their skill to be reliably assessed. Under this qualification, the highest Test batting average belongs to Australia's Sir Donald Bradman, with 99.94. Given that a career batting average over 50 is exceptional, and that only four other players have averages over 60, this is an outstanding statistic. The fact that Bradman's average is so far above that of any other cricketer has led several statisticians to argue that, statistically at least, he was the greatest sportsman in any sport.[3] As at 21 October 2016, Adam Voges of Australia has recorded an average of 72.75 from 27 innings played, but only 20 innings completed.

Batting averages in One Day International (ODI) cricket tend to be lower than in Test cricket,[4] because of the need to score runs more quickly and take riskier strokes and the lesser emphasis on building a large innings. It should also be remembered, especially in relation to the ODI histogram above, that there were no ODI competitions when Bradman played.

If a batsman has been dismissed in every single innings, then their total number of runs scored divided by the number of times they have been out gives exactly the average number of runs they score per innings. However, for a batsman with innings which have finished not out, this statistic is only an estimate of the average number of runs they score per innings – the true average number of runs they score per innings is unknown as it is not known how many runs they would have scored if they could have completed all their not out innings. If their scores have a geometric distribution then total number of runs scored divided by the number of times out is the maximum likelihood estimate of their true unknown average.[5]

Batting averages can be strongly affected by the number of not outs. For example, Phil Tufnell, who was noted for his poor batting,[6] has an apparently respectable ODI average of 15 (from 20 games), despite a highest score of only 5 not out, as he scored an overall total of 15 runs from 10 innings, but was out only once.[7]

A different, and more recently developed, statistic which is also used to gauge the effectiveness of batsmen is the strike rate. It measures a different concept however – how quickly the batsman scores (number of runs from 100 balls) – so it does not supplant the role of batting average. It is used particularly in limited overs matches, where the speed at which a batsman scores is more important than it is in first-class cricket.

Leading Test batting averages

(Source: Cricinfo Statsguru 6 August 2016)

| Rank | Batsman | Tests | Innings | N.O. | Runs | Highest | Ave[8] | Career dates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | |

52 | 80 | 10 | 6996 | 334 | 99.94 | 1928–1948 |

| 2 | |

17 | 25 | 7 | 1432 | 269* | 79.55 | 2015–present |

| 3 | |

23 | 41 | 4 | 2256 | 274 | 60.97 | 1963–1970 |

| 4 | |

22 | 40 | 4 | 2190 | 270* | 60.83 | 1930–1954 |

| 5 | |

54 | 84 | 9 | 4555 | 194 | 60.73 | 1924–1935 |

| 6 | |

42 | 77 | 11 | 3937 | 215 | 59.65 | 2010–present |

| 7 | |

20 | 31 | 5 | 1540 | 243 | 59.23 | 1931–1939 |

| 8 | |

82 | 131 | 15 | 6806 | 256 | 58.67 | 1955–1968 |

| 9 | |

48 | 81 | 5 | 4455 | 207 | 58.61 | 1948–1958 |

| 10 | |

85 | 140 | 16 | 7249 | 336* | 58.45 | 1927–1947 |

Table shows players with at least 20 innings completed.

* denotes not out.

Major League Baseball

In baseball, the batting average (BA) is defined by the number of hits divided by at bats. It is usually reported to three decimal places and read without the decimal: A player with a batting average of .300 is "batting three-hundred." A point (or percentage point) is understood to be .001 . If necessary to break ties, batting averages could be taken to more than three decimal places.

Henry Chadwick, an English statistician raised on cricket, was an influential figure in the early history of baseball. In the late 19th century he adapted the concept behind the cricket batting average to devise a similar statistic for baseball. Rather than simply copy cricket's formulation of runs scored divided by outs, he realized that hits divided by at bats would provide a better measure of individual batting ability. This is because while in cricket, scoring runs is almost entirely dependent on one's own batting skill, in baseball it is largely dependent on having other good hitters on one's team. Chadwick noted that hits are independent of teammates' skills, so used this as the basis for the baseball batting average. His reason for using at bats rather than outs is less obvious, but it leads to the intuitive idea of the batting average being a percentage reflecting how often a batter gets on base, whereas in contrary, hits divided by outs is not as simple to interpret in real terms.

In modern times, a season batting average higher than .300 is considered to be excellent, and an average higher than .400 a nearly unachievable goal. The last player to do so, with enough plate appearances to qualify for the batting championship, was Ted Williams of the Boston Red Sox, who hit .406 in 1941, though the best modern players either threaten to or actually do achieve it occasionally, if only for brief periods of time. There have been numerous attempts to explain the disappearance of the .400 hitter, with one of the more rigorous discussions of this question appearing in Stephen Jay Gould's 1996 book Full House.

Ty Cobb holds the record for highest career batting average with .367, 9 points higher than Rogers Hornsby who has the second highest average in history at .358. The record for lowest career batting average for a player with more than 2,500 at-bats belongs to Bill Bergen, a catcher who played from 1901 to 1911 and recorded a .170 average in 3,028 career at-bats. The modern-era record for highest batting average for a season is held by Napoleon Lajoie, who hit .426 in 1901, the first year of play for the American League. The modern-era record for lowest batting average for a player that qualified for the batting title is held by Rob Deer, who hit .179 in 1991. While finishing six plate appearances short of qualifying for the batting title, Adam Dunn of the Chicago White Sox hit .159 for the 2011 season, twenty points (and 11.2%) lower than the record. The highest batting average for a rookie was .408 in 1911 by Shoeless Joe Jackson.

For non-pitchers, a batting average below .230 is often considered poor, and one below .200 is usually unacceptable. This latter level is sometimes referred to as "The Mendoza Line", named for Mario Mendoza (a lifetime .215 hitter), a stellar defensive shortstop whose defensive capabilities just barely made up for his offensive shortcomings. The league batting average in Major League Baseball for 2004 was just higher than .266, and the all-time league average is between .260 and .275.

In rare instances, MLB players have concluded their careers with a perfect batting average of 1.000. John Paciorek had three hits in all three of his turns at bat. Esteban Yan went two-for-two, including a home run. Hal Deviney's two hits in his only plate appearances included a triple, while Steve Biras, Mike Hopkins, Chet Kehn, Jason Roach and Fred Schemanske also went two-for-two. A few dozen others have hit safely in their one and only career at-bat.

Sabermetrics, the study of baseball statistics, considers batting average a weak measure of performance because it does not correlate as well as other measures to runs scored, thereby causing it to have little predictive value. Batting average does not take into account walks or power, whereas other statistics such as on-base percentage and slugging percentage have been specifically designed to measure such concepts. Adding these statistics together form a player's On-base plus slugging or "OPS". This is commonly seen as a much better, though not perfect, indicator of a player's overall batting ability as it is a measure of hitting for average, hitting for power and drawing bases on balls.

In 1887, Major League Baseball counted bases on balls as hits. The result of this was skyrocketed batting averages, including some near .500, and the experiment was abandoned the following season.

Qualifications for the batting title

The Major League Baseball batting averages championships (often referred to as "the batting title") is awarded annually to the player in each league who has the highest batting average. Ty Cobb holds the MLB (and American League) record for most batting titles, officially winning 11 in his pro career.[9] The National League record of 8 batting titles is shared by Honus Wagner and Tony Gwynn. Most of Cobb's career and all of Wagner's career took place in what is known as the Dead-Ball Era, which was characterized by higher batting averages and much less power, whereas Gwynn's career took place in the Live-Ball Era.

To determine which players are eligible to win the batting title, the following conditions have been used over the sport's history:[10]

- Pre-1920 – A player generally is required to appear in at least 100 or more games when the schedule was 154 games, and 90 games when the schedule was 140 games. An exception to the rule was made for Ty Cobb in 1914, who appeared in 98 games but had a big lead and was also a favorite of League President Ban Johnson.

- 1920–1949 – A player had to appear in 100 games to qualify in the National League; the AL used 100 games from 1920–1935, and 400 at-bats from 1936–1949. The NL was advised to adopt 400 at-bats for the 1945 season, but League President Ford Frick refused, feeling that 100 games should stand for the benefit of catchers and injured players. (Taffy Wright is often erroneously said to have been cheated out of the 1938 batting title; he batted .350 in exactly 100 games, with 263 ABs. Jimmie Foxx hit .349, in 149 games and 565 AB. But since the AL requirement that year was 400 at-bats, Foxx's batting title is undisputed.)

- 1950–1956 – A player needed 2.6 at-bats per team game originally scheduled. (With the 154-game schedule of the time, that meant a rounded-off 400 at-bats.) From 1951–1954, if the player with the highest average in a league failed to meet the minimum at-bat requirement, the remaining at-bats until qualification (e.g., 5, if the player finished the season with 395 ABs) were hypothetically considered hitless at-bats; if his recalculated batting average still topped the league, he was awarded the title. This standard applied in the AL from 1936–1956.

- 1957 to the present – A player has needed 3.1 plate appearances per team game originally scheduled; thus, players were no longer penalized for walking so frequently, nor did they benefit from walking so rarely. (In 1954, for example, Ted Williams batted .345 but had only 386 ABs, while topping the AL with 136 walks. Williams thus lost the batting title to Cleveland's Bobby Ávila, who hit .341 in 555 ABs.) In the 154-game schedule, the required number of plate appearances was 477, and since the era of the 162-game schedule, the requisite number of PAs has been 502. (Adjustments to this 502 PA figure have been made during strike-shortened seasons, such as 1972, 1981, 1994, and 1995.)

From 1967 to the present, if the player with the highest average in a league fails to meet the minimum plate-appearance requirement, the remaining at-bats until qualification (e.g., 5 ABs, if the player finished the season with 497 plate appearances) are hypothetically considered hitless at-bats; if his recalculated batting average still tops the league, he is awarded the title. This is officially called Rule 10.22(a), but it is also known as the Tony Gwynn rule because the Padres' legend won the batting crown in 1996 with a .353 average on just 498 plate appearances (i.e., was four shy). Gwynn was awarded the title since he would have led the league even if he'd gone 0-for-4 in those missing plate appearances. His average would have dropped to .349, five points better than second-place Ellis Burks' .344.[11] In 2012, a one-time amendment to the rule was made to disqualify Melky Cabrera from the title. Cabrera requested that he be disqualified after serving a suspension that season for a positive testosterone test. He had batted .346 with 501 plate appearances, and the original rule would have awarded him the title over San Francisco Giants teammate Buster Posey, who won batting .336.[12][13]

All-time leaders

| # | Player | Avg [14] | Team(s) | Year(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ty Cobb | .366 | Detroit, Philadelphia (AL) | 1905–28 |

| 2 | Rogers Hornsby | .358 | St. Louis (NL), New York (NL), Boston (NL), Chicago (NL), St. Louis (NL), St. Louis (AL) | 1915–37 |

| 3 | Shoeless Joe Jackson | .356 | Philadelphia (AL), Cleveland, Chicago (AL) | 1908-20 |

| 4 | Lefty O'Doul | .349 | New York (AL), Boston (AL), New York (NL), Philadelphia (NL), Brooklyn | 1919–23, 1928–34 |

| 5 | Ed Delahanty | .346 | Philadelphia (NL), Cleveland (PL), Philadelphia (NL), Washington | 1888–1903 |

| 6 | Tris Speaker | .345 | Boston (AL), Cleveland, Washington (AL), Philadelphia (AL) | 1907–28 |

| 7 | Ted Williams | .344 | Boston (AL) | 1939–42, 1946–60 |

| 7 | Billy Hamilton | .344 | Kansas City (AA), Philadelphia (NL), Boston (NL) | 1888–1901 |

| 9 | Dan Brouthers | .342 | Troy, Buffalo, Detroit (NL), Boston (NL), Boston (PL), Brooklyn (NL), Baltimore (NL), Louisville, Philadelphia (NL), New York (NL) | 1879–96, 1904 |

| 9 | Babe Ruth | .342 | Boston (AL), New York (AL), Boston (NL) | 1914–35 |

Other contexts

Following from usage in cricket and baseball, batting average has come to be used for other statistical measures of performance and in the general usage on how a person did in a wide variety of actions.

An example is the Internet Archive, which uses the term in ranking downloads. Its "batting average" indicates the correlation between views of a description page of a downloadable item, and the number of actual downloads of the item. This avoids the effect of popular downloads by volume swamping potentially more focused and useful downloads, producing an arguably more useful ranking.

References

- ↑ "Baseball Statistics". Cosmic Baseball Association. Archived from the original on 31 October 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-29.

- ↑ See Rae, Simon; W.G. Grace: A Life; p. 26. ISBN 0571178553

- ↑ "Sir Donald Bradman". Players and Officials. Cricinfo.com. Retrieved 2006-04-27.

- ↑ – Highest Career Battin Average in ODIs

- ↑ Das, S. (2011). "On Generalized Geometric Distributions: Application to Modeling Scores in Cricket and Improved Estimation of Batting Average in Light of Notout Innings". Social Science Research Network.

- ↑ Cricinfo – The Jack of all rabbits

- ↑ Phil Tufnell

- ↑ "Test Career Highest Batting Averages". Cricinfo. Archived from the original on 12 February 2007. Retrieved 2007-02-12.

- ↑ "Year-by-Year League Leaders for Batting Average". Sports Reference, Inc. Archived from the original on 9 February 2007. Retrieved 2007-01-30.

- ↑ "Leaderboard Glossary – Baseball". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved 2012-05-26.

- ↑ http://triblive.com/sports/2424892-74/cabrera-batting-crown-rule-league-baseball-gwynn-mccutchen-347-anyone

- ↑ "Cabrera, Posey are MVPs". The State. Associated Press. 16 November 2012. Archived from the original on 13 December 2012.

- ↑ Baggarly, Andrew. "Melky Cabrera ruled ineligible to win batting crown". CSN Bay Area. Archived from the original on 13 December 2012.

- ↑ "Career Leaders for Batting Average". Baseball Reference. Retrieved 2007-01-30.