Alphonse Bertillon

| Alphonse Bertillon | |

|---|---|

|

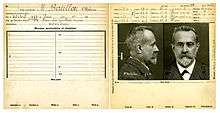

Mug shot of Bertillon | |

| Born |

24 April 1853 Paris, France |

| Died |

13 February 1914 (aged 60) Münsterlingen, Switzerland |

| Occupation | law enforcement officer and biometrics researcher |

| Parent(s) |

|

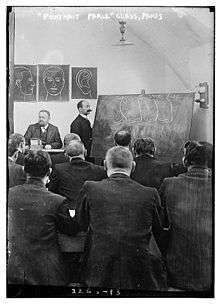

Alphonse Bertillon (French: [bɛʁtijɔ̃]; 24 April 1853 – 13 February 1914) was a French police officer and biometrics researcher who applied the anthropological technique of anthropometry to law enforcement creating an identification system based on physical measurements. Anthropometry was the first scientific system used by police to identify criminals. Before that time, criminals could only be identified by name or photograph. The method was eventually supplanted by fingerprinting.[1]

He is also the inventor of the mug shot. Photographing of criminals began in the 1840s only a few years after the invention of photography, but it was not until 1888 that Bertillon standardized the process.

Biography

Bertillon was born in Paris.[2] He was a son of statistician Louis-Adolphe Bertillon and younger brother of the statistician and demographer Jacques Bertillon.

After being expelled from the Imperial Lycée of Versailles, Bertillon drifted through a number of jobs in England and France, before being conscripted into the French army in 1875. Several years later, he was discharged from the army with no real higher education, so his father arranged for his employment in a low-level clerical job at the Prefecture of Police in Paris. Thus, Bertillon began his police career on 15 March 1879 as a department copyist.

Being an orderly man, he was dissatisfied with the ad hoc methods used to identify the increasing number of captured criminals who had been arrested before. This, together with the steadily rising recidivism rate in France since 1870,[3] motivated his invention of anthropometrics. His road to fame was a protracted and hard one, as he was forced to do his measurements in his spare time. He used the famous La Santé Prison in Paris for his activities, facing jeers from the prison inmates as well as police officers.

Bertillon also created many other forensics techniques, including forensic document examination, the use of galvanoplastic compounds to preserve footprints, ballistics, and the dynamometer, used to determine the degree of force used in breaking and entering.

The nearly 100-year-old standard of comparing 16 ridge characteristics to identify latent prints at crime scenes against criminal records of fingerprint impressions was based on claims in a 1912 paper published in France by Bertillon.[4] The images of fingerprints which Bertillon published in his paper and upon which his claims were based were found later to have been altered and were forgeries.[5]

Bertillon died 13 February 1914 in Münsterlingen, Switzerland.

Bertillon and the Dreyfus Affair

Bertillon was a witness for the prosecution in the Dreyfus affair in 1894 and again in 1899. He testified as a handwriting expert and claimed that Alfred Dreyfus had written the incriminating document (known as the “bordereau”). However, he was not a handwriting expert, and his convoluted and flawed evidence was a significant contributing factor to one of the most infamous miscarriages of justice – the condemnation of the innocent Dreyfus to life imprisonment on Devil’s Island.

Using a complex system of measurements, he attempted to prove that Dreyfus had disguised his handwriting by imitating his own handwriting as if someone else was doing so, so that if anyone thought the bordereau was in Dreyfus’s hand, he would be able to say that someone else had forged his writing. Both courts martial evidently accepted this, and Dreyfus was convicted. The verdict of the second court martial caused a huge scandal, and it was eventually overturned.

Bertillon was by many accounts regarded as extremely eccentric. According to Maurice Paleologue, who observed him at the second court-martial, Bertillon was “certainly not in full possession of his faculties”. Paleologue goes on to describe Bertillon’s argument as “a long tissue of absurdities”, and writes of “his moonstruck eyes, his sepulchral voice, the saturnine magnetism” which made him feel that he was “in the presence of a necromancer”.[6]

Bertillon pretended that his graphological system was based on mathematical probability calculus. A later expertise undertaken in 1904 by three renowned mathematicians, Henri Poincaré, Jean Gaston Darboux, and Paul Émile Appell, concluded that Bertillon's system was deprived of any scientific value and that he had failed both to apply the method and to present his data properly.[7] With this key evidence against Dreyfus debunked, he was finally acquitted in 1906.

Legacy

Bertillon is referenced in the Sherlock Holmes story The Hound of the Baskervilles, in which one of Holmes’ clients refers to Holmes as the “second highest expert in Europe” after Bertillon. Also, in "The Naval Treaty", speaking of the Bertillon system of measurements Holmes himself “... expressed his enthusiastic admiration of the French savant.”

In the Arsène Lupin story The Escape of Arsène Lupin by Maurice Leblanc, Lupin escapes by exploiting the same flaws in anthropometry that led to its eventual disuse. In Surfeit of Lampreys by Ngaio Marsh Chief Inspector Roderick Alleyn touches on the system in Chapter 14, Part 1.

Bertillon is also referenced in the Caleb Carr novel The Alienist. The Isaacson brothers, who are detectives, mention that they are trained in Bertillon system. The Bertillon Measurements are also mentioned in Sax Rohmer's Fu Manchu-inspired The Emperor of America (Cassel, 1929, p. 61), the Ross MacDonald novels The Drowning Pool and "Blue City" (p.30), and Yves Fey's mystery Floats the Dark Shadow. Bertillonage is mentioned in Chapter 4 and in an appendix of the mystery "The Assassin in the Marais" by Claude Izner.

Bertillon appears in Eric Zencey's novel Panama.

Bertillon is the main character of the third episode of Czech TV series The Adventures of Criminology called “Bertillonage”.

Bertillon is also mentioned in the second episode of the seventh season of FX television series Archer.

Bertillon was also referenced in a series called Elementary. Season 2, Episode 17 (Ears to you).

See also

nice beard dead

References and sources

- References

- ↑ Olsen, Robert D. Sr (November 1987). "A Fingerprint Fable: The Will and William West Case". Identification News. 37 (11).

- ↑ Rhodes, Henry T.F. Rhodes (1956). Alphonse Bertillon: Father of Scientific Detection. New York: Abelard-Schuman. p. 27.

- ↑ Ginzburg 1984, p. 105

- ↑ "Les empreintes digitales", Archives d’anthropologie criminelle, pp. 36–52

- ↑ Miller, Clifford G. (8 March 2013) Fingerprint Identification Not Scientific Nor Infallible & Based On Fraud. The Law Society Advocacy Section Newsletter.

- ↑ Paleologue, Maurice (1957) My Secret Diary of the Dreyfus Case, Secker and Warburg, p. 197

- ↑ Rapport de MM. les experts, 1904

- Sources

- Ginzburg, Carlo (1984). "Morelli, Freud, and Sherlock Holmes: Clues and Scientific Method". In Eco, Umberto; Sebeok, Thomas. The Sign of Three: Dupin, Holmes, Peirce. Bloomington, IN: History Workshop, Indiana University Press. pp. 81–118. ISBN 978-0-253-35235-4. LCCN 82049207. OCLC 9412985. Ginzburg describes Bertillon's role in the development of forensic science. This essay is a discussion of the conjectural paradigm as evidenced by the methods of Giovanni Morelli, Sigmund Freud and Sherlock Holmes in the light of Charles Sanders Peirce's logic of making good guesses or abductive reasoning.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Alphonse Bertillon. |

- The Adventure of Criminalistics (Dobrodružství kriminalistiky)

- Criminocorpus: Alphonse Bertillon and the Identification of Persons 1880–1914

- "Central Missouri State University: Criminal Justice: Alphonse Bertillon". Archived from the original on 13 July 2001. Retrieved 2013-06-10.

- Example of Bertillon Measurements in practice

- Instructions signalétiques by Alphonse Bertillon

- Ancestral Criminal Records – includes Bertillon cards.