Bethnal Green tube station

| Bethnal Green | |

|---|---|

|

Southwestern entrance | |

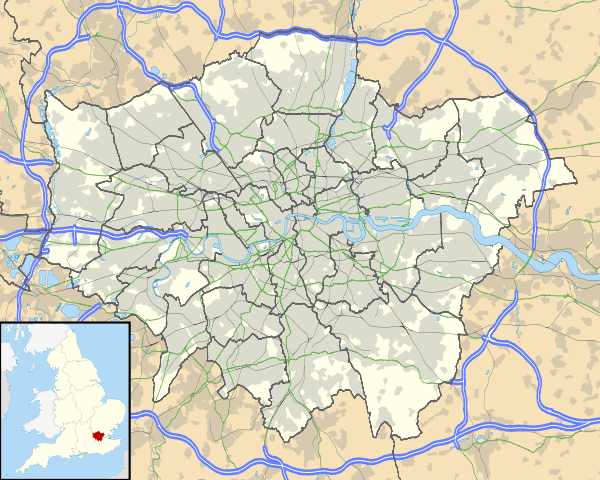

Bethnal Green Location of Bethnal Green in Greater London | |

| Location | Bethnal Green |

| Local authority | Tower Hamlets |

| Managed by | London Underground |

| Owner | Transport for London |

| Number of platforms | 2 |

| Fare zone | 2 |

| London Underground annual entry and exit | |

| 2012 |

|

| 2013 |

|

| 2014 |

|

| 2015 |

|

| Railway companies | |

| Original company | London Passenger Transport Board |

| Key dates | |

| 4 December 1946 | Station opened |

| Other information | |

| Lists of stations | |

| WGS84 | 51°31′38″N 0°03′20″W / 51.5272°N 0.0556°WCoordinates: 51°31′38″N 0°03′20″W / 51.5272°N 0.0556°W |

|

| |

Bethnal Green is a London Underground station in Bethnal Green in Greater London, England. The station is situated in the East End of London and is served by the Central line lying between Liverpool Street and Mile End stations. The station was opened as part of the long planned Central line eastern extension on 4 December 1946; before that it was used as an air-raid shelter. On 3 March 1943, 173 people were killed in a crush while attempting to enter the shelter.

The station is an example of the "New Works Programme 1935 - 1940" style adopted by London Transport for its new tube stations. Extensive use is made of pale yellow tiling, originally manufactured by Poole Pottery. This has been replicated during the 2007 modernisation although several panels of original tiling were retained on the platforms. The finishes include relief tiles, showing symbols of London and the area served by the London Passenger Transport Board, designed by Harold Stabler. The station entrances, all in the form of subway access staircases to the subterranean ticket hall, all show the design influences of Charles Holden, the consulting architect for London Transport at this time.

Wartime disaster

Construction of the Central line's eastern extension was started in the 1930s, and the tunnels were largely complete at the outbreak of the Second World War although rails were not laid. The facilities at Bethnal Green were requisitioned in 1940 at the onset of the first Blitz and administration was assigned to the local authority, the Metropolitan Borough of Bethnal Green, under the supervision of the 'Regional Commissioners', the generic name for London civil defence. Heavy air raids began in October and thousands of people took shelter there, often remaining overnight. However, usage of the shelter dwindled in 1941 as the Luftwaffe was redirected away from London and against the Soviet Union. A relative lull occurred although the number of shelterers rose again when retaliatory bombing in response to Royal Air Force raids was expected.

This was the case on 3 March 1943, after British media reported a heavy RAF raid on Berlin on the night of 1 March. The air-raid Civil Defence siren sounded at 8:17 pm, triggering a heavy but orderly flow of people down the blacked-out staircase from the street. A middle-aged woman and a child fell over, three steps up from the base and others fell around her, tangled in an immovable mass which grew, as they struggled, to nearly 300 people. Some managed to get free but 173, most of them women and children, were crushed and asphyxiated. Some 60 others were taken to hospital. News of the disaster was withheld for 36 hours and reporting of what had happened was censored, giving rise to allegations of a cover-up, although it was in line with existing wartime reporting restrictions. Among the reports which never ran was one filed by Eric Linden of the Daily Mail, who witnessed the disaster. The story which was reported instead was that there had been a direct hit by a German bomb. The results of the official investigation were not released until 1946.[2]

At the end of the war, the Minister of Home Security, Herbert Morrison, quoted from a secret report to the effect that there had been a panic, caused by the discharge of anti-aircraft rockets, fired from nearby Victoria Park. But other authorities who looked into what had happened disagreed; the Shoreditch Coroner, Mr W R H Heddy,[3] said that there was "nothing to suggest any stampede or panic or anything of the kind"; Mr Justice Singleton, summarising his decision in Baker v Bethnal Green Corporation, an action for damages by a bereaved widow,[4] said "there was nothing in the way of rushing or surging" on the staircase; the Master of the Rolls, Lord Greene, reviewing the lower court's judgement[5] said "it was perfectly well known .. that there had been no panic". Lord Greene also rebuked the Ministry for getting the case to be held in secret.

The Baker lawsuit was followed by other claims, resulting in a total payout of nearly £60,000, the last of which was made in the early 1950s. The secret official report, by a Metropolitan magistrate, Laurence Rivers Dunne, acknowledged that Bethnal Green Council had warned London Civil Defence, in 1941, that the staircase needed a crush barrier to slow down the crowds, but was told that would be a waste of money.[6]

It was not until 50 years after the disaster that a discreet commemorative plaque was erected at the site.

The crush at Bethnal Green is thought to have been the largest single loss of civilian life in the UK in World War II and the largest loss of life in a single incident on the London Underground network. The largest number killed by a single wartime bomb was 107 at Wilkinson's Lemonade Factory in North Shields (1941),[7] though there were many more British civilians killed in single bombing raids.[8]

Although the deaths were not due to enemy action, the 173 dead are all recorded by name by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission among the 527 civilian war dead in the Bethnal Green Municipal Borough.[9] All are recorded as "Died [date] in Tube Shelter accident".[10]

The "Stairway to Heaven Memorial Trust" was established in 2007 to create a memorial to those who died in the disaster. Planning permission has been granted for a memorial in the form of a bronze staircase with 173 points of light, designed by local architects Harry Patticas and Jens Borstlemann.[11]

On 1 April 2016, Dr Joan Martin, who was on duty as a junior casualty officer at the nearby Queen Elizabeth Hospital for Children and led the medical team dealing with the dead and wounded from the incident, told BBC Radio 4's Eddie Mair about her personal experiences on the evening of the disaster, and its long-term effects on her life.[12]

'TUBE' Art Installation

In November 2013 sound artist Kim Zip [13] created an installation [14] commemorating the Bethnal Green Tube Disaster. The work was backed by London's Whitechapel Gallery and promoted as part of the organisation's 'First Thursdays' [15] initiative for popular art.

'TUBE' [16] exhibited over a period of four weeks in the belfry of Sir John Soane's St John on Bethnal Green Church. St John's overlooks the site of the tragedy and was commandeered as a temporary mortuary on the night of 3 March 1943.

Derailment on the Central line

On 5 July 2007, a Central line train was derailed when it hit a roll of fire blanket which had been blown out of a cross passage between the two tunnels by the strong cross winds.[17]

London Fire Brigade sent 14 fire engines to the scene, including four urban search and rescue vehicles.

Connections

London Buses routes 8, 106, 254, 309, 388, D3 and D6 and night routes N8 and N253, and National Express Coaches route A9 serve the station.

Gallery

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bethnal Green tube station. |

-

Westbound platform looking east

-

Eastbound platform looking east

-

Roundel on Westbound platform

-

Memorial to the 1943 disaster, on southeastern staircase

References

- 1 2 3 4 "Multi-year station entry-and-exit figures" (XLS). London Underground station passenger usage data. Transport for London. April 2016. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- ↑ Bethnal Green - disaster at the tube, Wednesday 24 September 2003, 19.30 BBC Two Archived 13 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Nat. Archives MEPO 2/1942

- ↑ The Times, 19 July 1944

- ↑ The Times, 9 December 1944

- ↑ Nat.Archives PREM 4/40/15

- ↑ http://northshields173.org

- ↑ "Bethnal Green Tube disaster marked 70 years on". BBC News. 3 March 2013. Archived from the original on 2013-03-06.

- ↑ CWGC Cemetery record, civilian casualties Bethnal Green Municipal Borough.

- ↑ Example CWGC Casualty record for Betty Diana Aarons.

- ↑ "The Appeal". Stairway to Heaven Memorial Trust. Archived from the original on 2008-03-07.

- ↑ "Bethnal Green Tube Disaster: 'I tried to black it out'". BBC News Online. 1 April 2016. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- ↑ "Bomb Everyone". Bomb Everyone website. 1 January 2011.

- ↑ "Remembrance art marks Bethnal Green's 1943 air-raid shelter disaster". East London Advertiser. 4 November 2013.

- ↑ "Whitechapel Gallery's First Thursdays". Whitechapel Gallery. 31 October 2013.

- ↑ "Kim Zip Presents TUBE on Soundcloud". Soundcloud. 1 November 2013.

- ↑ Rail Accident Report - Derailment of a London Underground Central Line train near Mile End station 5 July 2007 (PDF). Department of Transport - Rail Accident Investigation Branch. January 2008. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-01-30.

External links

- Cooper, Nick. "The Underground at war". Subterra. Archived from the original on 2009-12-14.

- "The hush-hush catastrophe". The Guardian. 15 February 2003. Archived from the original on 2003-03-02.

- "Bethnal Green Memorial". Stairway to Heaven Memorial Trust. Archived from the original on 2007-12-21. Site relating to proposed new memorial. It also lists the victims' names.

- Charity Commission. Stairway to Heaven Memorial Trust, registered charity no. 1118618.

- Bernier, Nichole (2 December 2010). "Interview with writer/researcher of the Bethnal Green tragedy of 3 March 1943". The report. Beyond the margins.

- "Bethnal Green Disaster 3rd March 1943". BBC History. BBC. 2 December 2005. Archived from the original on 2013-06-30.

| Preceding station | Following station | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Central line |