Blue Comet

|

A reproduced sign for former Blue Comet service at Communipaw Terminal in Jersey City | |||||

| Overview | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Service type | Inter-city rail | ||||

| Status | Discontinued | ||||

| Locale | New Jersey, United States | ||||

| First service | February 21, 1929 | ||||

| Last service | September 27, 1941 | ||||

| Former operator(s) | Central Railroad of New Jersey | ||||

| Route | |||||

| Start | Jersey City, New Jersey | ||||

| End | Atlantic City, New Jersey | ||||

| Average journey time | 3 hours | ||||

| Service frequency | varied | ||||

| On-board services | |||||

| Seating arrangements | Reserved coach seat | ||||

| Catering facilities | Dining car | ||||

| Observation facilities | Observation car | ||||

| Technical | |||||

| Track gauge | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) | ||||

| |||||

The Blue Comet was a named passenger train operated by Central Railroad of New Jersey from 1929 to 1941 between the New York metropolitan area and Atlantic City.

Designed by Central Railroad of New Jersey (CNJ) president R.B. White in 1928, this train whisked passengers from Communipaw Terminal in Jersey City to Atlantic City, making the total trip from Manhattan (via ferry to the Jersey City terminal) to Atlantic City in three hours. The Blue Comet would take NY&LB trackage to Red Bank, then follow the Southern Division Main Line to Winslow Junction, where it would travel over the Atlantic City Railroad's tracks to Atlantic City.[1]

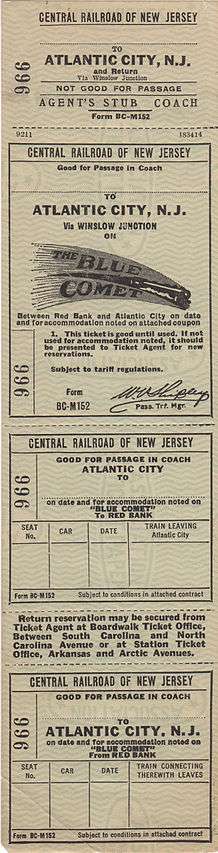

The colors chosen for the Blue Comet's locomotive and passenger cars were ultramarine and Packard Blue, for the sea, cream, for the sandy coastal beaches, and nickel. The tickets for the train were blue, the dining car chairs were upholstered in blue linen, and the porters were dressed in blue as well. The locomotive was capable of 100 miles per hour, and the railroad claimed the train itself was the first east of the Mississippi to be equipped with roller bearings for easy starting and stopping.[2]

History

Inaugurated on February 21, 1929, the Blue Comet was designed to provide coach passengers with deluxe equipment, accommodations, and service at a regular coach fare. The first revenue passengers to board the CNJ's new flagship at Communipaw Terminal were Miss Beatrice Winter and Miss Helen Lewis of New York. As the Blue Comet made its way to Atlantic City, it was put on display for patrons, railfans, and local residents to see and inspect. Thousands of spectators along the line came to see the new train. This was due in part to a clever ad campaign via radio and newspaper which spurred public interest. Following its first arrival in Atlantic City, a formal dinner was held for railroad officials at the Hotel Dennis. The Blue Comet was published in several periodicals and trade magazines such as Railway Age (March 1929), Fortune (The first issue in February, 1930), The Modelmaker, and several advertisements for ELESCO Superheaters and Feedwater Heaters. Periodic articles about the train would also appear in the New York Times, Philadelphia Enquirer, and local papers such as the Red Bank Register. It was even featured in a British 1937 Gallaher Ltd collection of tobacco cards entitled "Trains of the world." Billed as the "Seashore's Finest Train", it was dubbed a "Symphony in Blue." Lionel founder Joshua Lionel Cowen, was among those who frequently rode the Blue Comet. Inspired by the train's elegant beauty, speed, and the sublime power of its towering locomotive, Lionel offered a standard gauge model of the train in 1930. This gave the train and Lionel an almost mythical quality.

There were three factors behind the creation of the Blue Comet:

- To eliminate passenger service south of Winslow Junction, and replace rail service with bus connections.

- To better compete with the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR) for Atlantic City passengers.

- To eliminate a costly Pullman parlor car lease, in which the CNJ had a loss ten months of the year.

The Blue Comet would offer extra accommodations at the regular coach fare and have assigned seats so passengers knew exactly where they would sit. The PRR charged extra for its all-parlor car Atlantic City Limited and New York Limited. In addition, the PRR charged extra fees for parlor cars on the Nellie Bly. The Blue Comet ran on-schedule 97 percent of the time for the first five years.[3] A billboard was installed on the Routes 33 and 34 overpass at Farmingdale listing the times the train would pass that area.

The Blue Comet was initially a success but fell victim to the Great Depression. Service was reduced to a single round trip by April 1933. Also that year, the PRR and Reading Company (RDG) consolidated their southern New Jersey routes and formed the Pennsylvania-Reading Seashore Lines.[4] After the merger, the PRR owned two-thirds of the trackage. Reports from travelers indicate that Blue Comet information was not readily available at the Atlantic City station. This had the Blue Comet service at a disadvantage, as PRR Atlantic City-New York information was readily available for passengers heading to points north.

Ocean County stops for the Blue Comet included Lakewood and Lakehurst. The Lakewood stop was to pick up and drop off passengers as well as Jolly Tar Trail bus service. The stop at Lakehurst was for people needing a connection for the Barnegat Branch, later replaced by Jolly Tar Trail service during off-peak hours in the early 1930s, and for the locomotives to take on water. For residents of the more isolated sections of the Pine Barrens, the Blue Comet's railroad crews would drop off newspapers. In Chatsworth, the train slowed as it went through the center of town on its return from Atlantic City to disperse a bundle of the daily papers - including The New York Times, Philadelphia Inquirer, among other big-city publications - which had been provided for passengers to read while on board. This goodwill gesture offered a way for locals who did not have radios or electricity to stay informed on current events. Community lore has it that residents would show their appreciation by bringing baskets of freshly picked berries for the crew. However, this anecdote has been disputed by some who lived in the area at the time and insisted the express train did not stop in a location where such an exchange would have happened.

The train's last run was on September 27, 1941, Its main competitor, the Nellie Bly, lasted until 1961.

Accidents

On Friday, December 26, 1935 the Blue Comet experienced a small fire in the roof of the dining car Giaccobini. The fire was discovered while the train was en route to Red Bank by the chef, who promptly alerted the steward Lewis Herring. The two men attempted to put out the fire themselves using fire extinguishers, however the origin of the fire was inaccessible. An overheated flue from the coal stove had cause some of the roof structure to burn between the ceiling and the roof of the dining car. Red Bank firefighters were summoned as the train pulled into the station, and the fire was quickly put out. Damage was estimated at only $50.00. The passengers were unaware that there was any problem until they were politely asked to leave the dining car at the station. The Blue Comet was delayed for 39 minutes while the fire was put out and the dining car removed from service. The train arrived in Atlantic City only 22 minutes behind schedule.[5]

On August 19, 1939, train No 4218 was traveling east-bound with a consist of (1) combine (Halley), (1) coach (D'Arrest), one diner (Giacobini), (1) coach (Winnecki), and (1) observation car (Beila). Engine No. 820, a 4-6-2 Pacific was on point. Conductor Walsh and Engineman Thomas were in charge of the train, which was carrying 49 passengers and crew. Extraordinarily heavy rains fell in the area throughout the day. It is estimated that roughly 13 1⁄2 inches of rain fell, and about 10 3⁄4 inches fell between 2 and 6 pm. The train's crew had reduced speed from the usual 70 mph to between 35-40 mph, as visibility was poor and the crew had been given a message at Winslow Junction to keep a lookout for sand on the crossings due to the heavy rains. Near milepost 86, about a mile west of Chatsworth[6] station, the train hit a washout at 4:37 pm. The surface water had overwhelmed two 24-inch culverts, and undermined the roadbed. The engine and tender made it across the damaged track, with the rear tender truck being derailed. The rear truck floating lever was damaged, rendering the tender brakes inoperative. The entire 5-car consist, however, had become uncoupled from the tender and derailed.[7] The cars came to rest in general line with the track, and were leaning at various angles. Roughly 500 feet of track was destroyed. When the train failed to arrive at Chatsworth Station, personnel and local residents waded over a mile through the woods in water waist deep in parts to reach the wreck. Reports that one hundred people were killed led to a flurry of ambulances from northern parts of the state. Actually, only forty-nine people were on board. The injured included 32 passengers, 4 dining car employees, 1 porter, and 1 train service employee. The chef, Joseph Coleman, was crushed and badly scalded in the kitchen of the dining car when the stove fell on top of him as the car overturned. He later died from his injuries.[8] The majority of the injuries were minor, resulting from the flying wicker chairs in the observation car. CNJ crews replaced about six hundred feet of damaged track in approximately forty-eight hours. A relief train arrived a few hours later to take the remaining passengers. An investigation concluded that the derailment was caused by the washout which resulted from the unusually heavy rainfall. Today, the mainline track and wreck site are abandoned and very overgrown.

All of the equipment involved in the wreck was repaired and returned to service, except for the dining car Giaccobini. Being a steel-clad wooden car, it was unable to withstand the forces of the wreck and was too badly damaged to repair. It was used as a rail yard freight office until it was eventually scrapped.

Crossing accidents

On Friday, January 10, 1936, William Taylor, 42, an African-American farmhand, was instantly killed when his produce truck was struck by the Blue Comet while crossing the tracks at Finkel's Lane, Shrewsbury. Mr. Taylor was employed on the farm owned by C. Borderson of Shrewsbury and had been transporting produce from one side of farm to the other. The crossing was on private property and had no watchman. The engineer, William J. Smith of Elizabeth, was taken into custody for questioning and later released. Engineer Smith stated that the bell of the Blue Comet had been kept ringing ever since the train pulled out of the Red Bank station. The whistle, he said, had also been sounded. The truck was demolished and the locomotive badly damaged. A steam valve cap from the automatic safety control of the engine was damaged and the steam escaped. After a delay of about an hour, the train limped into Eatontown station, where an extra locomotive from Red Bank took up the interrupted journey.[9]

Shortly before noon on January 14, 1936, a National Biscuit Company trailer-truck, stalled on the tracks of the New York & Long Branch railroad at the Shrewsbury Avenue crossing, was struck by a southbound Pennsylvania train. The driver, Joseph Clark, 53, of Corona, Long Island, jumped from the cab of the truck before the train crashed into it. According to the driver, the motor of the truck stalled just as it reached the tracks. A wrecking crew removed the truck from the tracks so as to permit the Blue Comet, due at Red Bank at 10:04 o'clock, to pass.[10]

At 6:10 PM on Monday, September 8, 1941, a mother and two of her children were killed when the Blue Comet express train crashed into a light delivery truck at an unprotected crossing not far from their home. They were Mrs. Antionette Macciocca, 35 of White Horse Pike Elm, and her two daughters, Gloria 13, and Joanne, 4. The accident took place as Mrs. Mocciocca was driving back to her home after visiting a neighbor to obtain advice on canning vegetables. The crash occurred a few minutes after the Blue Comet left Hammonton, bound from Atlantic City to Jersey City. State police said the crossing was marked with a sign but was without watchman, crossing bells, or signal lights. The train stopped several hundred yards up the tracks after the incident and was delayed for an hour. The crew included A. Feryling, Phillipsburg, engineer, and J.F. Walsh, Somerville.[11]

Equipment

Three brand-new G3s Pacific locomotives were assigned to the train; numbers 831, 832 and 833. The CNJ totally refurbished sixteen cars for Blue Comet service, inside and out. The train and its engines were painted in Packard Blue to suggest the sea and the sky. The passenger cars all had a cream band running the length of the side at the windows to evoke the sand of the shore. The paint scheme was unusual, since the road name did not appear on each car; rather, only the name of the train, "THE BLUE COMET", appeared in gold lettering on the letter board. Each car was named for a different comet. The name of each car was placed in gold lettering at the middle of each side below the windows. The underframes and trucks were painted royal blue and varnished. The locomotives' marker lights, headlights, handrails, coupler lifting rods, cylinder head covers, and back valve chambers were nickel-plated. Side rods were polished. The name of the train was painted in gold lettering on a blue nameboard that was mounted to the front of the smoke box just below the Elesco feedwater heater. The train was also known by its distinctive whistle. Mounted on the fireman's side of the steam dome, it was usually angled forward. While the manufacturer and cadence of the specific whistle has not been verified (none are known to exist), it is reported to have been a long-bell 3-chime steamboat whistle similar to a Hancock or Star Brass 6" long-bell 3-chime.

In later years as ridership declined, the usual G3s locomotives were sometimes used in other service. As a result, a variety of motive power was used. Sometimes the Blue Comet was pulled by other CNJ fast Pacifics such as #820, or Camelback locomotives such as #592. 592 was one of the CNJ's fastest Camelbacks and could frequently be found on point in Blue Comet service.

Inside the train, the cars were lavishly furnished. Each car was clad in circassian walnut with a gold inlay pattern. The headliners were cream colored. Window shades were made of blue Spanish pantasote. The luggage racks were nickel-plated. Each car had a drinking fountain by the North Pole Sanitary Drinking Fountain company of Chicago. Collapsible cone-shaped paper cups with the train's logo were available via a dispenser above the fountain. Coaches were fitted out with 64 individual seats which rotated, nickel-plated coat hooks, and umbrella holders mounted to the back of the seats. Upholstery was Persian Blue, rendered in figured mohair. The seats were triple-cushioned, 48 rattan lounge chairs in silver and blue lined either side of the observation car. These were upholstered in Persian blue Avalon plush, with a gold-tinted floral pattern. The coaches and combines had a men's lavatory and toilet located at one end of the car on opposite sides of the aisle. The coaches and observation car were fitted out with a generous women's lounge with an adjoining toilet. The lounge had a full-length mirror, two wicker arm chairs, a boudoir chair, and a cup and towel vendor. The floor covering was a Persian blue carpet with a gold modern pattern. The combines had 48 blue leather bucket seats. The flooring was a blue-and-cream diagonal checkerboard linoleum tile. This same flooring was utilized in the vestibules and lavatories as well as the observation platform. The dining car could accommodate 36 patrons. Porters in blue uniforms served savory dishes and homemade goodies. The tables were set with the finest embroidered blue tablecloths with the train's logo, special china and flatware, and a silver base lamp with parchment shade. The lampshades had an astral pattern of comets and stars, and tinted lightbulbs were employed to cast a soft blue glow. Apparently the fresh apple pie with a slice of sharp cheddar cheese was a popular offering. Each train consisted of a baggage car, combine-smoker, coaches, and an observation car. The diner accompanied the early morning trip to Atlantic City and the evening return to Jersey City.

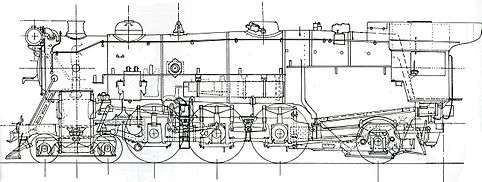

Locomotive

- Builder: Baldwin Locomotive Works

- Year Built: 1928

- Tractive Force: 46,841 lbs.

- Weight on Drivers: 197,660 lbs.

- Total Weight: 326,470 lbs.

- Factor of Adhesion: 4.21

- Pilot Truck:

- Commonwealth cast steel w/ pedestals cast integral with frame

- Weight on Front Truck: 65,850 lbs.

Front Elevation Erection Drawing of Baldwin G-3s Heavy Pacific 4-6-2 locomotive

Front Elevation Erection Drawing of Baldwin G-3s Heavy Pacific 4-6-2 locomotive - Front Truck: 36"

- Frames: Vanadium Cast Steel

- Driving Wheel Base: 13'-10'

- Driver Diameter: 79"

- Trailing Truck:

- Commonwealth Delta type

- Weight on Trailing Truck: 62,960 lbs.

- Wheel Diameter: 55"

Drive train

- Cylinders: 26"x 28"

- Valve Gear: Walschaerts

- Piston Valves: 13"

- Pistons: 5" diameter. Heat treated Steel Casting.

- Reverse: Alco Power Reversing Gear

- Crossheads: Underhung type with forged steel box guides.

- Side Rods: Floating Bushings, grease cups forged solid & integral

- Counterbalancing: 55% of the reciprocating weight

Suspension

- Chrome Silicon Manganese driving & truck springs.

Firebox

- Firebox Dimensions: 126-1/8"x 97-1/4"

- Stoker: Type B

Boiler

- Steam Pressure: 230 lbs.

- Boiler Diameter 1st Ring: 78"

- Number of 2" Flues: 251

- Number of 5-3/8" Flues: 36

- Length of Flues/Tubes: 228"

- Grate Area: 84.3 SF

- Superheater: Type "A" w/36 heating elements

- Total heating surfaces: 4,647 SF

- Elesco Feedwater Heater mounted on front of smoke box above the headlamp.

Lubrication system

- Nathan Eight Feed mechanical lubricator w/ 20 pint capacity.

Throttle

- Chambers backhead throttle valve

Drifting valves

- Automatic

Automatic train control

- Union Switch & Signal coded continuous

- (2) Westinghouse Simplex Air Compressors mounted on right side of boiler.

Tender

- Commonwealth one-piece cast steel water bottom underframe.

- Tender Water Capacity: 10,000 Gallons

- Tender Fuel Capacity: 15 Tons bituminous coal

- Weight of Tender: 217,000 lbs.

- Total Engine & Tender: 543,470 lbs.

- Wheel Base Engine & Tender: 72'-2"

- Overall Height to top of Cab: 15'-0-7/8"

Rolling stock

- Diner: Giacobini 81

- Combines: Halley 300, Encke 302

- Baggage cars: Olbers 391, Barnard 392

- Coaches: Tuttle 1170, Holmes 1171, Westphal 1172, D'Arrest 1173, Faye 1174, Spitaler 1175, Winnecke 1176, Brorsen 1177

- Observation cars: DeVico 1178, Biela 1179, Tempel 1169 [12]

As passenger traffic diminished, the G3s were withdrawn from Blue Comet service and other locomotives pulled the train. Frequently, one would find camelback locomotive 592 at the point,[13] or other Pacifics. Pacific 820 was on the point for the only derailment of the Blue Comet on August 19, 1939.

-

Blue Comet locomotive.

-

Observation platform.

-

Interior of observation car.

-

Smoking lounge.

-

Interior of coach car.

-

The dining car.

-

Side view of locomotive.

Crew

Conductors

- Joe Ross

- Joseph F. Walsh

- Walter G. Cline

Engineers

- George L. Robinson

- John Vary Wait

- John Decker

- Thomas

- A. Feryling

- William J. Smith

Firemen

- James Plunkett

- (x)Cinque

- Warren Crater

- John Weckman

Trainmen

- Paul Kennedy

- James B. Roemer

Chefs

- Joseph L Coleman

Dining car stewards

- Lewis Herring

Dining car waiters

- (x) Saunders

- (x) Adams

Porters

- James S. McKennan

Disposition

All of the G3s Pacific 4-6-2 locomotives were scrapped by Luria Brothers sometime around 1954-55.

Coach "Winnecke", 1176, was scrapped in Red Bank during the 1980s. In its last years, it had been used as a locker room. Various pieces of Winnecke were salvaged and eventually donated by the United Railroad Historical Society of New Jersey to the Black River & Western Railroad's restoration of CNJ coach 1009.

CNJ camelback locomotive #592 is preserved in the roundhouse at the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Museum in Maryland.[13]

In Tuckahoe, New Jersey the Tri-State Railway Historical Society, Inc., has former Blue Comet observation car "Tempel" (later known as CNJ car #1169) parked awaiting restoration.[14] The historical society would like to restore the car and use it in passenger service along the Cape May Seashore Lines.[15]

Blue Comet observation car "Biela" was moved to Clinton, New Jersey in the 1970s and continues to serve as part of a restaurant there. Biela was one of the cars involved in the wreck at Chatsworth in 1939.[16]

The "De Vico" (later known as CNJ #1178) observation car was in use by New Jersey Transit as an inspection car from 1982 until 1993.[17] The car, renumbered NJT-1, was donated in 2003 to the United Railroad Historical Society (URHS) of New Jersey, an organization that plans to restore the car. It currently is located in Boonton, NJ and has been recently painted in Blue Comet livery.[18][19] The

URHS also owns two coaches "Westphal" (later known as CNJ #1172) and "D'Arrest" (later known as CNJ #1173).[19] Both are presently located at Winslow Junction, NJ with no definitive plans for restoration.

The combine "Halley" #300 was reconfigured, repainted and used in service on the Santa Fe Southern Railway. "Halley", a smoker/combine, has been modified a bit with the removal of the vestibules, and the baggage area window has been blanked out.

The dining car "Giaccobini" was too badly damaged in the 1939 wreck. It was never returned to service and spent the rest of its days as a freight office. It was eventually scrapped.

In 2010 a "Jersey Coast" commuter club car, formerly used along the North Jersey Coast Line (but not in Blue Comet service), was rebuilt to appear like a Blue Comet observation car by the Whippany Railway Museum in Whippany, New Jersey.[20]

Legacy

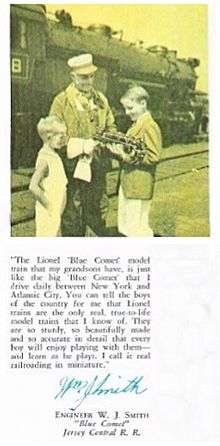

- In the 1930s the Lionel Corporation produced a Blue Comet model train, which is now considered a desirable collectable. While the set was popular, it bore little resemblance to the actual train.[21][22]

Lionel Ad.

Lionel Ad. - A sixth season episode of HBO's The Sopranos is titled "The Blue Comet".[23] In the episode toy train buff and mobster Bobby Baccalieri is murdered in a hobby shop as he bargains for an antique Lionel Blue Comet set.

- The Comet passenger railcar class of the 1970s and later was named to honor the Blue Comet.

- In December 1975 a special Blue Comet Nostalgia Train operated with a steam locomotive from Raritan Bay to Bay Head along the former New York and Long Branch Railroad (today's North Jersey Coast Line).[24] The nostalgia trip was filmed and appeared in a Christmas special edition of the Tomorrow television program with host Tom Snyder on December 25, 1975.

- Rivarossi produced a special HO-scale anniversary edition in 1979. It consisted of the 1978 steam locomotive 4-6-2 Heavy Pacific 831 CNJ plus two sets of four different coaches. The set was not prototypical of the actual train.[25][26] International Hobby Corporation reproduced the Rivarossi HO sets, including a DCC ready locomotive.

- Overland Brass made an HO-scale limited edition of the Blue Comet G3s Pacific locomotive. These models are accurately detailed and considered valuable.

- Bethlehem Car Works makes an HO version of the prototypical coaches, diner, and combine. However, these models are not painted in Blue Comet livery.

- In 1979 The Little Rascals Christmas Special, Spanky learns that his mother (voiced by Darla Hood) is getting him a Blue Comet model train set, only to later find out that his mother had to sell her winter overcoat to buy the train. He then tries to raise the funds with the gang in order to buy the coat back.[27]

- MTH produced several versions of the Blue Comet in O gauge. One is a faithful replica of the 1930s Lionel. Another under their Rail King line is more prototypical, and features sound and synchronized smoke features.

- Aristo Craft produced a G-scale Blue Comet set. Like other manufacturers' Blue Comet representations, some minor details deviate from the original.

- Documentary filmmaker Robert A. Emmons, Jr., details the history of the Blue Comet in the 2009 documentary film De Luxe: The Tale of the Blue Comet.[28][29]

- In 1998 Lionel produced a second Blue Comet with a model 4-6-4.

- The Black Cat Motorcycle Club of Lansdale, Pennsylvania often encountered the Blue Comet on their rides to the Jersey Shore. Members renamed the club "Blue Comet MC" in 1937.[30]

- In 2001 Lionel produced another Blue Comet model train with a real model 4-6-2; only 1,000 were produced. This model was an entire set.

- Also in 2001 Lionel produced a separate two car pack consisting of Combo car Halley, and Coach car Tuttle.

- In 2003 Lionel produced a separate model of diner "Giacobini".

- In 2009, Auran produced CGI models of the Blue Comet train as an add-on for its Trainz Railroad Simulator 2009 PC game. This package contains two G-3s models, one in the Blue Comet's blue livery and one in the later black livery, as well as a P-47 model in a similar, but unlined version of the latter livery. The package also includes models of the train's baggage, combine, coach, diner and observation cars.

- In 2012 Lionel produced a fourth Blue Comet model train with a real model 4-6-2. The locomotive and four cars are sold separately.

References

- ↑ When the Blue Comet started service in 1929 the Atlantic City Railroad was wholly owned by the Reading Railroad. By 1933 the Pennsylvania-Reading Seashore Lines were jointly owned by the Reading Company and the Pennsylvania Railroad.

- ↑ "New De Luxe Train Viewed". New York Times. Feb 15, 1929. Retrieved 2011-02-25.

- ↑ Wilk, Tom; Waltzer, Jim (December 1, 2010). "Blue Comet Memories Keep Chugging – Boardwalk Empire Notes". Atlantic City Weekly. Retrieved 2010-12-28.

- ↑ Wentzel, Don (Spring 1994). "Winslow Junction Revisited". South Jersey Magazine.

- ↑ "Fire in Dining Car". Red Bank Register. December 26, 1935.

- ↑ Bradley, Stephen; Bradley, Jennifer. "Blue Comet". Retrieved 2010-12-25.

- ↑ Jerseyman (November 21, 2007). "The Travail of the Blue Comet". Ben Ruset & NJPineBarrens.com. Retrieved 2011-10-21.

- ↑ Whiten, Jon (August 19, 2011). "Today in History: Train Bound for Jersey City Crashes in the Pine Barrens". Jersey City Independent. Retrieved 2011-10-21.

- ↑ "Killed When Blue Comet Hits Truck". Red Bank Register. January 16, 1936.

- ↑ "Trailer-Truck Hit By Train; Driver Escapes". Red Bank Register. January 16, 1936.

- ↑ "Express kills Elm mother, two children". Hammonton News. Hammonton N.J. September 12, 1941.

- ↑ Laufer, Joseph M. "BLUE COMET, "THE SEASHORE'S FINEST TRAIN"". Archived from the original on 2009-10-29. Retrieved 2010-12-27.

- 1 2 Bradley, Stephen; Bradley, Jennifer. "Baltimore & Ohio Museum". Retrieved 2010-12-27.

- ↑ "Tempel". Retrieved 2010-12-28.

- ↑ Bradley, Stephen; Bradley, Jennifer. "Cape May Seashore Lines". Archived from the original on 2011-04-06. Retrieved 2010-12-28.

- ↑ "Clinton Station Diner". Retrieved 2010-12-28.

- ↑ Corso, Joseph (December 2001). "The Central Railroad of New Jersey". Retrieved 2010-12-28.

- ↑ Steinberg, Michael. "NJT-1 - NJ TRANSIT's Glorious Relic". Retrieved 2010-12-28.

- 1 2 "URHS of NJ Equipment Roster". Retrieved 2010-12-28.

- ↑ Tupaczewski, Paul R. "The Jersey Coast". Retrieved 2010-12-28.

- ↑ "Lionel Train Sets & Products: Operating Cars, Passenger Cars & Accessories: Blue Comet Passenger set (LOCO #831)". Lionel, LLC. Retrieved 2010-12-27.

- ↑ "Roadshow Archive : Lionel Blue Comet Train, ca. 1935". Retrieved 2010-12-28.

- ↑ The Blue Comet at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ "New York & Long Branch". Retrieved 2011-10-21.

- ↑ http://www.rivarossi-memory.it/Grandi_Treni/The_Blue_Comet.htm

- ↑ http://www.rivarossi-memory.it/Riva_Loco_Americane/Riva_Pacific.htm#Locomotiva_a_Vapore_4-6-2_Heavy_Pacific_-_Blue_Comet__Central_Railroad_of_New_Jersey__

- ↑ The Little Rascals' Christmas Special (TV 1979) at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ De Luxe: The Tale of the Blue Comet (2009) at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ Barna, John (February 26, 2011). "The tale of the 'Blue Comet' rail line to be explored at Camden County College event". Gloucester County Times. Retrieved 2011-10-21.

- ↑ "The History of BCMC". Blue Comet M.C. Retrieved 2011-10-21.

Further reading

- Rosenbaum, Joel; Gallo, Tom (1983). The Seashore’s Finest Train: The Blue Comet. Piscataway, NJ: Railpace Company, Inc.

External links

- Bradley, Stephen; Bradley, Jennifer. "Blue Comet". Retrieved 2010-12-25.

- Laufer, Joseph M. "BLUE COMET, "THE SEASHORE'S FINEST TRAIN"". Archived from the original on 2009-10-29. Retrieved 2010-12-27.

- Staples, Robert A. "CENTRAL RAILROAD OF NEW JERSEY". Archived from the original on June 18, 2012. Retrieved 2010-12-28.