Bomb vessel

A bomb vessel, bomb ship, bomb ketch, or simply bomb was a type of wooden sailing naval ship. Its primary armament was not cannons (long guns or carronades)—although bomb vessels carried a few cannons for self-defence—but mortars mounted forward near the bow and elevated to a high angle, and projecting their fire in a ballistic arc. Explosive shells (also called bombs at the time) or carcasses were employed rather than solid shot. Bomb vessels were specialized ships designed for bombarding (hence the name) fixed positions on land. In the 20th century, the same role was carried out by battleships, cruisers, destroyers, and the purpose-built World War I- and II-era monitors.

Development

The first recorded deployment of bomb vessels by the English was for the Siege of Calais in 1347 when Edward III deployed single deck ships with bombardes and other artillery.[1] The first specialised bomb vessels were built towards the end of the 17th century, based on the designs of Bernard Renau d'Eliçagaray, and used by the French Navy.[2][3][4] They were first called galiote à bombe (a word derived from the Dutch galliot, denoting a short, beamy vessel well suited for the powerful downward recoil of its weapons).[5] Five such vessels were used to shell Algiers in 1682 destroying the land forts, and killing some 700 defenders. Two years later the French repeated their success at Genoa.[2] The early French bomb vessels had two forward-pointing mortars fixed side-by-side on the foredeck. To aim these weapons, the entire ship was rotated by letting out or pulling in a spring anchor.[3] The range was usually controlled by adjusting the gunpowder charge.[2] The French later adopted the word bombarde for this vessel,[6] but it should not to be confused with the horizontal fire, stone throwing bombard of earlier centuries.[7]

The French design was copied by the Royal Navy,[2] who continued to refine the class over the next century or more, after Huguenot exiles brought designs over to England and the United Provinces. The side-by-side, forward-pointing mortars were replaced in the British designs by mortars mounted on the centerline on revolving platforms. These platforms were supported by strong internal wooden framework to transmit the forces of firing the weapons to the hull. The interstices of the framework were used as storage areas for ammunition.

Early bomb vessels were rigged as ketches with two masts. They were awkward vessels to handle, in part because bomb ketches typically had the masts stepped farther aft than would have been normal in other vessels of similar rig, in order to accommodate the mortars forward and provide a clear area for their forwards fire. As a result, by the 1800s British bomb vessels were designed as full rigged ships with three masts, and two mortars, one between each neighboring pair of masts.[8] Bomb vessels often had the front rigging made of chain, to better withstand the muzzle blast of the mortars.[3]

Mortars were the only kind of naval armament to fire explosive shells rather than solid shot until the invention of the Paixhans gun. Since it was considered dangerous to have large stocks of shells on board the ships that were firing them, and because the reinforced mortar platforms occupied so much space below decks, bomb vessels were usually accompanied by a tender to carry ammunition as well as the ordnance officers in charge of firing the mortars. However, as naval warfare became more advanced, bomb ships were also accompanied by frigates to protect them from direct assault by faster, smaller vessels.

Bomb vessels were traditionally named after volcanoes, or given other names suggestive of explosive qualities. Some were also given names associated with the underworld. Vessels of other types which were later converted to bomb ships generally retained their original names.

Bomb vessels were highly specialized and expensive to fit out and maintain, and only marginally suited for their secondary role as cruisers. Because bomb vessels were built with extremely strong hulls to withstand the recoil of the mortars, several were converted in peacetime as ships for exploration of the Arctic and Antarctic regions, where pack ice and icebergs were a constant menace. Most famously, these ships included HMS Erebus and HMS Terror. In this case, the volcanoes – Mount Erebus and Mount Terror on Ross Island in Antarctica – were named after the ships, instead of vice versa.

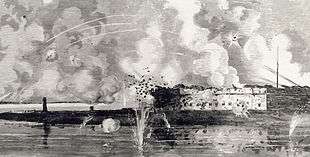

Although horizontal fire naval guns propelling explosive shells had entered all major navies by the 1840s (see Paixhans gun), there was still room for a specialized vessel on occasion. During the American Civil War, the Union fleet included armored gunboats armed with 13 inch mortars; the weapon weighed 17,250 lbs and its bedding another 4,500 lbs. They fired 204-lb shells, with a bursting charge of 7 lbs of gunpowder, and had a range of three miles. At this distance, the projectile spent 30 seconds in flight. They were used to attack several forts, for example Fort Pulaski, Georgia.[9]

Notable bomb vessels and actions

- The bomb vessels Racehorse and Carcass were further strengthened for an expedition of discovery to the North Pole in the 1770s. The uncompleted expedition included a young Horatio Nelson.

- Bomb vessels Discovery, Explosion, Hecla, Sulphur, Terror, Volcano, and Zebra participated in the 1st Battle of Copenhagen in 1801.

- Thunder, Vesuvius, Aetna, and Zebra participated in the 2nd Battle of Copenhagen in 1807.

- Thunder and Aetna additionally participated in the Battle of the Basque Roads in 1808 (this action was also notable for including three rocket vessels in support of the bombs).

- The "bombs bursting in air" recorded by Francis Scott Key at the Battle of Baltimore in 1814 were provided by the Volcano, Meteor, Devastation, Aetna, and a new Terror.

- Bomb vessels were part of the British forces that attacked Fort St. Philip in January 1815, during the War of 1812. This engagement is known as the Siege of Fort St. Philip.

- Another Hecla and her sister ship Fury were used by William Edward Parry on a series of voyages to the Arctic between 1819 and 1827.

- During the Battle of Veracruz in 1838, the bomb vessels Cyclope and Vulcain fired most of the shells used by the French, and scored decisive hits on Mexican ammunition depots.

- Erebus and Terror served as exploration vessels in the expeditions of James Clark Ross to the Antarctic in 1840–1843, and of John Franklin to the Arctic in 1845–1848. Terror had also previously been used by George Back in his 1836–1837 Arctic expedition.

In fiction

The Commodore (published 1945), a Horatio Hornblower novel written by C. S. Forester, features several actions by British bomb vessels. The text includes a highly detailed account of the procedures used to load the mortars and aim, which involved anchoring fore-and-aft, receiving feedback from shot monitors, and precisely adjusting the aim using a spring-line attached to a windlass to adjust the direction of the shot, and by using sometimes tiny adjustments in the amount of charge to adjust the range. A later book, Hornblower in the West Indies, features a small portable "ship's mortar" mounted in a boat, used to bombard a target during a riverine operation.

In his stirring fictionalized account, war correspondent, author, and yachtsman G. A. Henty describes in vivid detail the deployment of ten bomb-ketches by the Spanish beseigers during the final period of the siege of Gibraltar.[10]

On September 13, 1781, a tremendous fire was suddenly opened with redhot shot and carcasses upon the enemy’s ten battering-ships that were lined up in the Bay of Gibraltar. By mid-afternoon most of the battering-ships and the Spanish admiral’s flagship were showing signs of being on fire.

By the early hours of September 14, eight of the battering-ships were in conflagration. Shortly after 5am two of the battering-ships exploded. Of the six battering-ships still in flames, three blew up before eleven o'clock. The other three burned to the waterline as the magazines had been flooded by the Spaniards before they abandoned the ships. The British hoped that the two remaining battering-ships might be saved to be sent home as trophies of the victory, but about noon one of them suddenly burst into flames and then blew up. The other was examined and found to be so damaged that she could not be saved. She was accordingly set on fire too and destroyed. Thus the whole of the ten battering-ships that were considered by their Spanish builders to be invincible were destroyed.

Over the next five months nothing of any importance took place till, on the 2nd of February, 1782, the Spanish commander sent a communication to advice that the preliminaries of a general peace had been signed by Great Britain, France, and Spain, and three days later the blockade at sea was discontinued, and the port of Gibraltar again open.

In The Ramage Touch by Dudley Pope (published 1979), Captain Lord Ramage and the crew of the Calypso frigate capture two bomb ketches, which they subsequently use to thwart a French invasion plan in the Mediterranean. Like the Hornblower books, The Ramage Touch describes in great detail the technical aspects of employing a bomb vessel during the Napoleonic era.

In H.M.S. Cockerell by Dewey Lambdin (published 1995), First Lieutenant Alan Lewrie is set ashore by his vindictive captain, for 'land service' during the Siege of Toulon. There Admiral Goodall gives him a bomb ketch, which he commands for several weeks until it is blown out of the water and sunk by a young Colonel of artillery named Buonaparte.

See also

References

- ↑ Royal Artillery Institution, ed. (1894). Journal of the Royal Artillery. Woolwich: Royal Artillery Institution. 21: 31. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - 1 2 3 4 Spencer Tucker (2000). Handbook of 19th century naval warfare. Naval Institute Press. pp. 4–5. ISBN 0-7509-1972-8.

- 1 2 3 Tuncay Zorlu (2008). Innovation and empire in Turkey: Sultan Selim III and the modernisation of the Ottoman Navy. I.B.Tauris. p. 128. ISBN 978-1-84511-694-1.

- ↑ Stephen Bull (2004). Encyclopedia of military technology and innovation. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 44. ISBN 978-1-57356-557-8.

- ↑ McLaughlan, Ian (2014). The Sloop of War 1650-1763. Seaforth Publishing. p. 109. ISBN 9781848321878.

- ↑ Encyclopédie des gens du monde, par une société de savans. 1834. p. 661.

- ↑ Augustin Jal (1848). Glossaire nautique: répertoire polyglotte de termes de marine anciens et modernes. Firmin Didot frères. p. 306.

- ↑ Leo Block (2003). To harness the wind: a short history of the development of sails. Naval Institute Press. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-55750-209-4.

- ↑ Stephen Bull (2004). Encyclopedia of military technology and innovation. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 112. ISBN 978-1-57356-557-8.

- ↑ George A. Henty, Held Fast for England: a tale of the siege of Gibraltar (1779-83) (London: Blackie, 1892) downloaded from the Internet Archive

Recommended reading

- Lavery, Brian: Nelson's Navy. ISBN 1-59114-611-9.

- Ware, Chris: The Bomb Vessel. ISBN 1-55750-071-1.

- Naval History of Great Britain