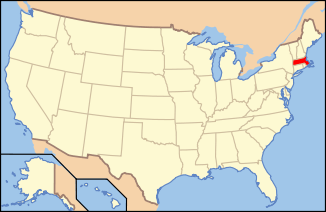

Boston Common

|

Boston Common | |

|

View of the water celebration on Boston Common on October 25, 1848 | |

| |

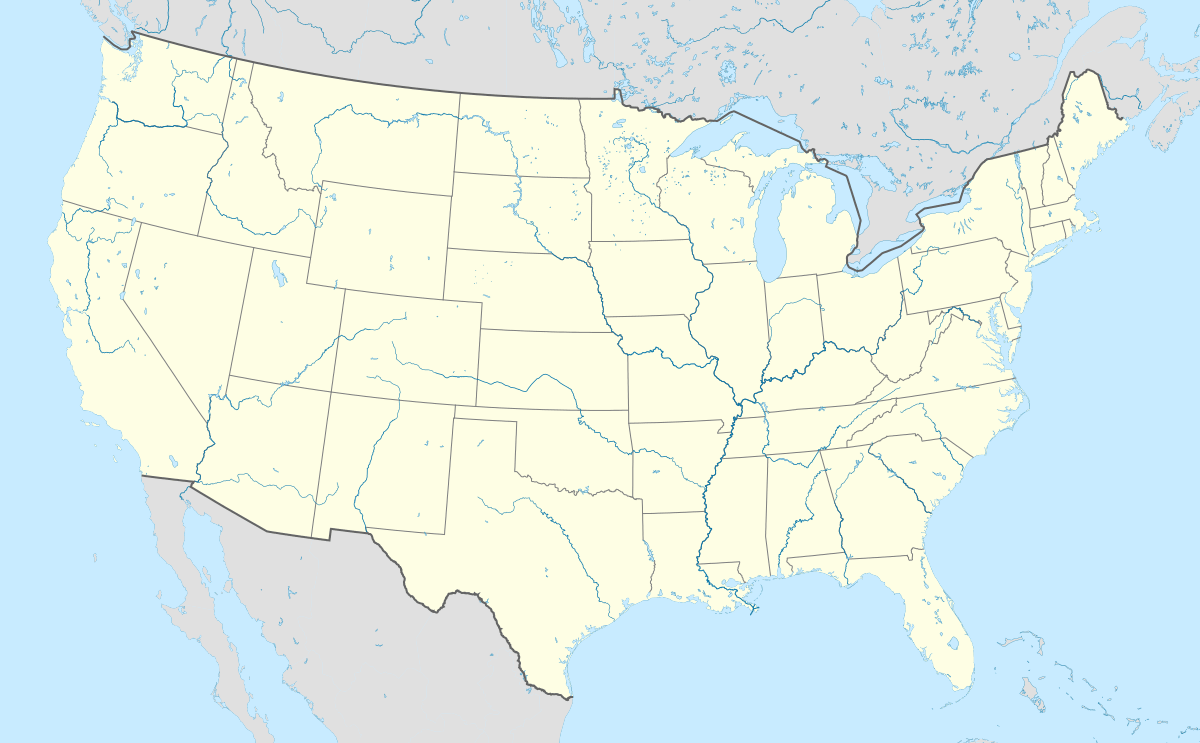

| Location | Boston, Massachusetts |

|---|---|

| Area | 50 acres (200,000 m2)[1] |

| Built | 1634 |

| Architect | Multiple, including Augustus St. Gaudens |

| NRHP Reference # |

72000144 (original) 87000760 (new) |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP |

July 12, 1972 (original, in NRHP also including Boston Public Garden) February 27, 1987 (new, in NHL of Boston Common alone)[2] |

| Designated NHLD | February 27, 1987[3] |

Boston Common (also known as the Common) is a central public park in downtown Boston, Massachusetts. It is sometimes erroneously referred to as the "Boston Commons".[4][5] Dating from 1634, it is the oldest city park in the United States.[6] The Boston Common consists of 50 acres (20 ha) of land bounded by Tremont Street, Park Street, Beacon Street, Charles Street, and Boylston Street. The Common is part of the Emerald Necklace of parks and parkways that extend from the Common south to Franklin Park in Roxbury. A visitors' center for all of Boston is located on the Tremont Street side of the park.

The Central Burying Ground is located on the Boylston Street side of Boston Common and contains the burial sites of the artist Gilbert Stuart and the composer William Billings. Also buried there are Samuel Sprague and his son, Charles Sprague, one of America's earliest poets. Samuel Sprague was a participant in the Boston Tea Party and fought in the Revolutionary War. The Common was designated as a Boston Landmark by the Boston Landmarks Commission in 1977.

History

_-_Walters_372766.jpg)

The Common's purpose has changed over the years. It was once owned by William Blaxton (often given the modernized spelling "Blackstone"), the first European settler of Boston, until it was bought from him by the Puritan founders of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. During the 1630s, it was used by many families as a cow pasture. However, this only lasted for a few years, as affluent families bought additional cows, which led to overgrazing, a real-life example of the Tragedy of the commons.[8] After grazing was limited in 1646 to 70 cows at a time,[9] the Boston Common continued to host cows until they were formally banned from it in 1830 by Mayor Harrison Gray Otis.[10]

The Common was used as a camp by the British before the American Revolutionary War, from which they left for the Battle of Lexington and Concord. It was used for public hangings up until 1817, most of which were from a large oak which was replaced with a gallows in 1769. On June 1, 1660, Quaker Mary Dyer was hanged there by the Puritans for repeatedly defying a law that banned Quakers from the Colony.[11] Dyer was one of the four Quakers executed on the Common and known as the Boston martyrs.[12][13]

On May 19, 1713, two hundred citizens rioted on the Common in reaction to a food shortage in the city. They later attacked the ships and warehouses of wealthy merchant Andrew Belcher, who was exporting grain to the Caribbean for higher profits. The lieutenant governor was shot during the riot.[14]

True park status seems to have emerged no later than 1830, when the grazing of cows was ended and renaming the Common as Washington Park was proposed. Renaming the bordering Sentry Street to Park Place (later to be called Park Street) in 1804[15] already acknowledged the reality. By 1836, an ornamental iron fence fully enclosed the Common and its five perimeter malls or recreational promenades, the first of which, Tremont Mall, had been in place since 1728, in imitation of St. James's Park in London. Given these improvements dating back to 1728, a case could be made that Boston Common is in fact the world's first public urban park, since these developments precede the establishment of the earliest public urban parks in England—Derby Arboretum (1840), Peel Park, Salford (1846), and Birkenhead Park (1847)—which are often considered the first.

Originally, the Charles Street side of Boston Common, along with the adjacent portions of the Public Garden, were used as an unofficial dumping ground, due to being the lowest-lying portions of the two parks; this, along with the Garden's originally having been a salt marsh, resulted in the portions of the two parks being "a moist stew that reeked and that was a mess to walk over", driving visitors away from these areas. Although plans had long been in place to regrade the Charles Street-facing portions of Boston Common and the Public Garden, the cost of moving the amount of soil necessary (approximately 62,000 cu yd (47,000 m3), weighing 93,000 short tons (84,000,000 kg), for the Common, plus an additional 9,000 cu yd (6,900 m3), weighing 14,000 short tons (13,000,000 kg), for the adjoining portions of the Public Garden) prevented the work from being undertaken. This finally changed in the summer of 1895, when the required quantity of soil was made available as a result of the excavation of the Tremont Street Subway, and was used to regrade the Charles Street sides of both Boston Common and the Public Garden.[16]

A hundred people gathered on the Common in early 1965 to protest the Vietnam War. A second protest happened on October 15, 1969, this time with 100,000 people protesting.[17]

Today, the Common serves as a public park for all to use for formal or informal gatherings. Events such as concerts, protests, softball games, and ice skating (on Frog Pond) often take place in the park. Famous individuals such as Martin Luther King Jr. and Pope John Paul II have made speeches there. Judy Garland gave her largest concert ever (100,000+) on the Common, on August 31, 1967.

It was declared a U.S. National Historic Landmark in 1987.[1][3] The Boston Common is a public park managed by the Boston Park Department. A private advocacy group, the Friends of the Public Garden, provides additional funding for maintenance and special events.[18]

On October 21, 2006, the Common became the site of a new world record, when 30,128 Jack-o'-lanterns were lit simultaneously around the park at the Life is good Pumpkin Festival.[19] The previous record, held by Keene, New Hampshire since 2003, was 28,952.[20]

On August 27, 2007, two teenagers were shot on the Common. One of the bullets fired during the shooting struck the Massachusetts State House.[21] A strict curfew has since been enforced, which has been protested by the homeless population of Boston.[22][23]

Notable features

Grounds

- The Common forms the southern foot of Beacon Hill.

- Boston Common is the southern end of Boston's Freedom Trail.

- The softball fields lie in the southwest corner of the Common.

- A grassy area forms the western part of the park and is most commonly used for the park's largest events. A parking garage lies under this part of the Common. A granite slab there commemorates Pope John Paul II's October 1979 visit to Boston.

- In 1913 and 1986 prehistoric sites were discovered on the Common indicating Native American presence in the area as far back as 8,500 years ago.[24]

- Since 1971 the Province of Nova Scotia has donated the annual Christmas Tree to the City of Boston as an enduring thank-you for the relief efforts of the Boston Red Cross and the Massachusetts Public Safety Committee following the Halifax Explosion of 1917. In recent years the tree has been located on the Common.

Structures

- A monumental inscription at the corner of Park Street and Tremont Street reads:

In or about the year of our Lord One Thousand Six Hundred thirty and four the then present inhabitants of the Town of Boston of whom the Hon John Winthrop Esq Gov of the Colony was Chiefe did treat and agree with Mr William Blackstone for the purchase of his Estate and any Lands living within said neck of Land called Boston after which purchase the Town laid out a plan for a trayning field for which ever since and now is used for that purpose and for the feeding of cattell.

- Plaque to the Great Elm tree, which had been adorned with lanterns to represent liberty, used as a point of fortification, and used for hangings.[25] It was destroyed in a storm in 1876.

- The Robert Gould Shaw Memorial to Robert Gould Shaw and the Afro-American 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry stands at Beacon and Park Streets, the northeast corner of the Common, opposite the State House.

- The Soldiers and Sailors Monument is a victory column on Flag Staff Hill in the Common, commemorating Civil War dead.

- The Boston Massacre Memorial was dedicated November 14, 1888.

- The Oneida Football Monument memorializes the Common as the site of the first organized football games in the United States, played by the Oneida Football Club in 1862.[26]

- Frog Pond, a public ice-skating rink in winter months, is situated in the northern portion.

- Brewer Fountain stands near the corner of Park and Tremont Streets, by Park Street Station. The 22-foot-tall (6.7 m), 15,000-pound (6,800 kg) bronze fountain, cast in Paris, was a gift to the city by Gardner Brewer. It began to function for the first time on June 3, 1868.

- Boylston and Park Street stations, the first two subway stations in the Western Hemisphere, lie underneath the southern and eastern corners of the park, respectively; both stations have been in near-continuous operation since the opening of the first portion of the Tremont Street Subway (now part of the MBTA's Green Line) on 1 September 1897.

- Parkman Bandstand, in the eastern part of the park, is used in musical and theatrical productions.

-

Beacon St. Mall, 19th century (photo by E.L. Allen)

-

Old Elm tree, 19th century

-

Plaque to the Great Elm tree

-

Boston Massacre Memorial

-

The Frog Pond

-

Boston Common

Neighboring structures

- The Massachusetts State House stands across Beacon Street from the northern edge of the Common.

- The Boston Public Garden, a more formal landscaped park, lies to the west of the Common across Charles Street (and was originally considered an extension of the Common).

- The Masonic Grand Lodge of Massachusetts headquarters sits across from the southern corner of the Common at the intersection of Boylston and Tremont Streets.

- Across from the southern corner of the Common, along Boylston and Tremont Streets, lies the campus of Emerson College.

- Across from the Common, to the southeast, Suffolk University has a dorm on Tremont Street.

Notable recurring events

- Commonwealth Shakespeare Company's Shakespeare on the Common

- Boston Lyric Opera's Outdoor Opera Series

- Ancient Fishweir Project Installation Event

- Massachusetts Cannabis Reform Coalition's Freedom Rally

- Lighting of the Christmas tree gifted by Halifax, Nova Scotia.

- Fireworks display on the evening of December 31 as part of Boston's First Night celebration

See also

- Boston martyrs

- Granary Burying Ground

- King's Chapel burying ground

- Boston Public Garden

- List of National Historic Landmarks in Boston

- National Register of Historic Places listings in northern Boston, Massachusetts

References

- 1 2 James H. Charleton (November 1985). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination: Boston Common" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved 2009-06-22. and Accompanying photos: one aerial from 1972 and three from 1985 (1.43 MB)

- ↑ National Park Service (2007-01-23). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- 1 2 "Boston Common". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Retrieved 2008-04-16.

- ↑ "Boston Common". City of Boston. Retrieved 2011-11-09.

- ↑ "Place Names: Boston English". Adam Gaffin and by content posters. Retrieved 2011-11-09.

- ↑ "Boston Common". CelebrateBoston.com. 2006. Retrieved 2011-03-26.

- ↑ "Boston Street Scene (Boston Common)". The Walters Art Museum.

- ↑ Loewen, James (1999). Lies Across America: What Our Historic Sites Get Wrong. New York: The New Press. p. 414. ISBN 0-9650031-7-5.

- ↑ Boston Common & Public Gardens - Great Public Spaces | Project for Public Spaces. PPS. Retrieved on 2013-08-21.

- ↑ Lowen, James (1994) Planning the City Upon a Hill: Boston Since 1630University of Massachusetts Press (Boston) ISBN 0-87023-923-6, ISBN 978-0-87023-923-6, p. 53

- ↑ Rogers, Horatio, 2009. Mary Dyer of Rhode Island: The Quaker Martyr That Was Hanged on Boston pp.1–2. BiblioBazaar, LLC

- ↑ J. Besse, A Collection of the Sufferings of the People called Quakers, 1753, Vol. 2, pp. 203-05.

- ↑ ODNB article by John C. Shields, ‘Leddra, William (d. 1661)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, Sept 2004; online edn, May 2007 , accessed 16 Aug 2009

- ↑ Zinn, Howard. A People's History of the United States. New York: Perennial, 2003. p.51 ISBN 0-06-052837-0

- ↑ "A Brief History of the Union Club". The Union Club of Boston. Retrieved 4 October 2012.

- ↑ Most, Doug (2014). The Race Underground: Boston, New York, and the Incredible Rivalry that Built America's First Subway. St. Martin's Press. pp. 233–234. ISBN 978-1-250-06135-5.

- ↑ Zinn, Howard. p.486

- ↑ http://www.friendsofthepublicgarden.org

- ↑ "Life is good" site Archived March 9, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Levenson, Michael; McCabe, Kathy (October 22, 2006). "A love in Common for pumpkins". The Boston Globe.

- ↑ Drake, John C. (August 28, 2007). "Shots on Common strike teens, State House". The Boston Globe.

- ↑ Abel, David (August 30, 2007). "Curfew targets crime on Common". The Boston Globe.

- ↑ "Homeless Protest Boston Common Curfew: Park Closed After 11 P.M.". TheBostonChannel.Com. 2007-08-30. Retrieved 2008-04-16.

- ↑ Research at Boston University. Bu.edu (2007-01-10). Retrieved on 2013-08-21.

- ↑ http://www.celebrateboston.com/sites/boston-common-great-elm.htm. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Winthrop Saltonstall Scudder, An historical sketch of the Oneida football club of Boston, 1862-1865 (Boston, 1926)

Further reading

- The public rights in Boston Common: Being the report of a committee of citizens. Boston: Press of Rockwell and Churchill, 1877 Google books

- Samuel Barber. Boston Common: a diary of notable events, incidents, and neighboring occurrences, 2nd ed. Boston: Christopher Publishing House, 1916. Google books

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Boston Common. |

- "A View on Cities," article on Boston Common

- Boston National Historical Park

- Friends of the Public Garden, an advocacy group formed in 1970 to preserve and enhance Boston Common

- Boston Common Frog Pond Foundation, a not-for profit body which overseas activities at The Common.

- New York Historical Society. Afternoon Rainbow, Boston Common from Charles Street Mall. Watercolor by George Harvey, 19th century

- BPL. Illus. by Winslow Homer

- City of Boston Archives. Ticket for July 4, 1883 bicycle race

- City of Boston, Boston Landmarks CommissionBoston Common Study Report

Coordinates: 42°21′18″N 71°03′56″W / 42.35500°N 71.06556°W

| Preceded by First location – beginning of trail |

Locations along Boston's Freedom Trail Boston Common |

Succeeded by Massachusetts State House |

.jpg)