Boundary Treaty of 1874 between Chile and Bolivia

| Treaty of Sucre | |

|---|---|

The border (24°S) was kept as 1866, but the Zone of Mutual Benefits was abolished | |

| Type | Boundary and economic |

| Signed | August 6, 1874 |

| Location | Sucre, Bolivia |

| Parties | Bolivia and Chile |

| Language | Spanish |

|

| |

The Boundary Treaty of 1874 between Chile and Bolivia, also called the Treaty of Sucre, was signed in Sucre on August 6, 1874 by the Bolivian Minister of Foreign Affairs Mariano Baptista and the Chilean plenipotentiary minister Carlos Walker Martínez. It superseded the Boundary Treaty of 1866 between Chile and Bolivia and it kept the border between both countries at the 24° South parallel from the Pacific Ocean to the eastern border of Chile.

The Treaty abolished the zone of bipartite tax collection on the export dues on minerals found between parallel 23°S and 25°S, and Bolivia promised explicitly in article 4 of the Treaty not to augment the existing taxes for twenty-five years on Chilean capital and industry.

To realize its Saltpeter Monopoly, Peru tried fruitless to prevent the signing of the treaty.

In February 1878, Bolivia imposed a new tax upon saltpeter and one year later began the War of the Pacific.

The Treaty of 1874 is of capital importance in the understanding of the causes of the War, because it established the legal position that existed between both countries when that war broke out.

Background

The 1866 Boundary Treaty

The 1866 treaty, the first boundary treaty between Bolivia and Chile, stipulated in seven articles:

- The international boundary will, in future, be drawn at the 24th parallel, and will be marked out on the ground "by means of visible and permanent signals — from the Pacific to the eastern boundary of Chile" by experts nominated by both countries.

- Notwithstanding the previous declaration, Chile and Bolivia shall divide between them the export duties paid on Guano and minerals in the zone included between the 23rd and 25th parallels, the Mutual Benefits Zone (MBZ).

- For the carrying out of this, Bolivia shall set up a custom-house in Mejillones which will be the only one authorized to receive these duties on the exportation of guano and metals from the aforesaid zone. Chile will have the right to nominate fiscal employees -who shall intervene in the counting house department of this aduana with full right of inspection. Bolivia will be conceded an equal right in the event of Chile establishing a custom-house in parallel 24°.

- All exports from the territory situated between the parallels of latitude 23° to 25° (MBZ), with the exception of guano and minerals, to be free from taxation, as will also be the natural production of Chile which may enter the country through Mejillones.

- By common accord between the two governments system will be adopted in the exploitation and sale of guano, and a similar agreement must he come to, to determine the duties on the exportation of minerals.

- Chile and Bolivia bind themselves to mutual preference in the event of the renting of the territories forming the subject matter of the present agreement, and to abstain from ceding them to any nation or individual.

- Eighty thousand pesos, withdrawn from ten percent, of the production of Mejillones will be granted to Bolivian concessionaires in guano exploitation whose, workings were suspended by act of the Chilean Government.

Nevertheless, both countries were dissatisfied with the treaty and looked for a solution.

The Lindsey-Corral agreement

On 5 December 1872, after difficult talks, Bolivian and Chilean negotiators Corral and Lindsay agreed to a clarification of the treaty of 1866. The Lindsay-Corral Protocol gave Chile the right to appoint customs officers to work alongside their Bolivian counterparts in the condominium zone, stipulated that tax rates could not be modified unilaterally, confirmed Bolivian acceptance of nitrates and borax as products included in the terms of the 1866 treaty, agreed that Bolivia would make a separate account of the amount to be received for taxes not derived from the common zone, and stated that the eastern limits of the common zone would be fixed by experts of both countries, and in case of disagreement, by a third nominated by the Emperor of Brazil. This Protocol was approved by Chile in January 1873.

A new grievance arose in August 1872 as Quintin Quevedo, a Bolivian diplomat, follower of Mariano Melgarejo who had been toppled as president in 1871, embarked on an expedition from Valparaiso against the Bolivian government, without any effective action of the Chilean authority, despite a warning by the Peruvian and Bolivian consulates about weapons and men on board the ships Maria Luisa and Paquete de Los Vilos.

Peru, which at that time enjoyed naval supremacy in South Pacific, responded with a naval demonstration in Mejillones, sending there the warships Huascar and the Chalaco. Peru's Minister of Foreign Affairs, Jose de la Riva Agüero, told the Chilean Government that Peru would not view with indifference the occupation of Bolivian territory by foreign forces.

The Peruvian government saw the Lindsay-Corral Protocol as an increase in the regional influence of Chile and urged Bolivia to reject it, and in fact on May 19, 1873 the Bolivian Assembly postponed approval to 1874. The Bolivian Assembly neither approved nor refused the treaty.

The increasing tensions between Peru and Chile

Because of the increasing tensions with Argentina and Peru, the Government of Chile ordered 1871 the purchase of two armored vessels, the Cochrane and the Blanco Encalada, which would shift the naval balance in the South Pacific in favor of Chile, but at the end of 1874.

On February 6, 1873, Peru and Bolivia signed the secret treaty of alliance between Peru and Bolivia; the parliamentary proceedings have disappeared since then.[1]

In Peru, which had large overseas debts, the economic situation deteriorated and the government imposed in 1873 a state control over production and sales of saltpeter. But there were also nitrate deposits in Bolivia and Chile. While the latter were not economically material, the exports from Bolivia by the Chilean Compañía de Salitres y Ferrocarriles de Antofagasta (CSFA) made Peruvian price controls impossible.

The Compañía de Salitres y Ferrocarriles de Antofagasta (CSFA) was a Chilean company, based in Valparaiso; a 29% minority share was held by the British Anthony Gibbs and Sons. From the 1860s the company had exploited the nitrate fields in Antofagasta, with a tax exemption license of the Bolivian government.[2]:99–100 The CSFA was the only competitor of Peruvian saltpeter in the international markets, and the urgent necessity to maintain the prices of saltpeter and guano brought the Peruvian government to intervene actively in the Bolivian saltpeter policy.

Peruvian historian Jorge Basadre asserts that the secret treaty and the Estanco were unrelated to each other, but Hugo Pereira Plascencia has contributed several items of evidences to the contrary: in 1873 the Italian author Pietro Perolari–Malmignati cited the Peruvian interest in defending its saltpeter monopoly against the Chilean production in Bolivia as the main cause of the secret treaty, and also said that the Peruvian Foreign Minister, José de la Riva-Agüero informed the Chilean Minister in Lima, Joaquín Godoy, about negotiations with Bolivia to expand the estanco in Bolivia.[3]

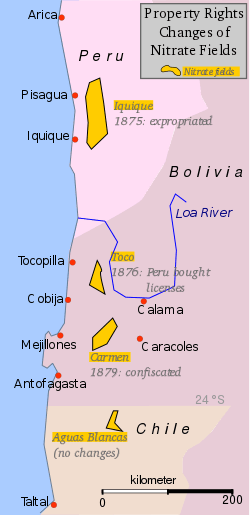

(Later, in 1875 the government expropriated the saltpeter industry and a full state monopoly on production and exports of saltpeter was imposed and in 1876 Peru bought Bolivian licences for nitrate fields in El Toco, Bolivia)

As the Peruvian Government knew from the rapprochement of Bolivia and Chile, its Chancellery took action to find some means of provoking the rupture and preventing the Chilean ships from leaving European waters, qualifying the conciliatory attitude of Walker Martinez as a blind and advising to Bolivia break the existing Treaties.[4]:2281 Peruvian Minister of Foreign Affairs Riva Agüero wrote in August 1873 to La Torre (Peruvian Plenipotentiary in Bolivia) as follows:[5]:71–72

- So, then, what Bolivia, ought to do is to waste no more time in time-killing discussions that conduce to nothing save to permit the arming of Chile. If the Government of Bolivia understands its own interests, if it does not want to lost part or the whole of its coast-line, it should utter its last word as regards the Treaty of 1866 and the Lindsay-Corral Convention: and it should definitely break these compacts whether by causing the extraordinary Assembly'to disapprove the one and resolve to substitute the other by reason of the insuperable difficulties which it has met with in practice, or by adopting some other measure conducive to the same end: always however so arranging matters that it is not Bolivia that breaks off relations but Chile that is obliged to do so.

- Relations once broken off and a state of war declared, Chile could not obtain possession of her ironclads, and lacking force with which of to attack, advantageously, would find herself in the necessity of accepting the mediation of Peru, which could in case of necessity — be converted into an armed mediation — if the forces of that republic sought to occupy Mejillones und Caracoles.

- To the foregoing consideration you may add other which will doubtless determine the decision of the Bolivian Government to adopt the line of conduct indicated. I refer to the practical certainty we have of the adhesion to the alliance of the Argentine Republic.

In 1874, Peruvian Navy officer Miguel Grau (Commander of the Navy during the war) adviced to the diplomacy of his country the internationalization of the Bolivian province of Antofagasta[6]

Content of the treaty

In August 1874, Bolivia and Chile substituted the Treaty of 1866 with a new Treaty that kept the 24th degree parallel as the boundary between both countries but ended the Mutual Benefits Zone defined in 1866 between the 23°S and 25°S. Further, Chile relinquished its share of export taxes on minerals shipped from Bolivia, and Bolivia agreed not to raise taxes on Chilean enterprises in Bolivia for 25 years.

Article 4 of the treaty is worded:

The duties of exportation that may be levied on minerals exploited in the zone referred to in the preceding articles shall not exceed those now in force, and Chilean citizens, industry, and capital shall not be subjected to any other contributions what ever except those now existing. The stipulations in this article shall last for twenty-five years.— Article 4, Chile-Bolivia Boundary Treaty of 1874

The Treaty of 1874 suffered formidable opposition in Bolivia. The suggestions of Peru had raised the aspirations of the country to such heights that mere peace would not suffice to satisfy them. The Legislative Assembly received the Treaty with violent hostility. There was a moment in which the Government found himself impotent to dominate the current of opposition, especially with reference to Article 4. which wounded the financial policy of Peru, which aimed to monopolize the nitrate production, and among the opposing bands in Congress attempts were made to make an arrangement on the basis of the deletion of this article.

The complementary protocol

On June 1875 a complementary protocol to the 1874 treaty was signed in order to amend articles 3 and 10 and incorporate an arbitration clause.

The breach of the treaty

In 1876 the Peruvian government bought the saltpeter licenses for "El Toco" fields in Bolivia through an intermediary, Henry Meiggs, the builder of the Peruvian railroads, but also with the involvement of Anthony Gibbs and Sons, the company that would owe Bolivia for the licenses. The picturesque agreement, as Crozier called it, about property would have long standing consequences; it was called "Caso Squire" in the Chilean courts after the war.[2]:116

In 1876 President Pardo urged Gibbs to ensure the success of the monopoly by limiting the production of the CSFA, and in 1878, Anthony Gibbs and Sons warned the management board of the CSFA that they would get trouble with a "neighbouring Government" [sic] if they insisted on swamping the market with their nitrate.[7]:69

Bolivian historian Querejazu cited George Hicks, manager of the Chilean CSFA, who knew that the highest bidder for the confiscated property of the CSFA on 14 February 1879 would be the Peruvian consul in Antofagasta.[8]

Having surrendered its claim to the disputed territories in return for a Bolivian promise not to increase tax,[9] Chile responded that the treaty did not allow for such a tax hike.[10] Bolivia suspended the tax in April 1878. In November Chile proposed a mediation and cautioned that Daza's refusal to cancel the tax would force Chile to declare null the 1874 Treaty. In December 1878 Bolivia, counting in its military alliance with Peru, challenged Chile and said the tax was unrelated to the treaty and that the claim of the CSFA should be addressed in Bolivian courts, and revived the tax.[11] When the company refused to pay the tax, Bolivia confiscated its property on 11 February and threatened to sell it on 14 February in order to liquidate the tax's debt.[12] On 14 February 1879, Chilean forces occupied Antofagasta.

Peru, bound with Bolivia by their secret treaty, tried to mediate, but on 1 March 1879 Bolivia declared war on Chile and called on Peru to activate their alliance, while Chile demanded that Peru declare its neutrality. On April 5, after Peru refused this, Chile declared war on both nations. The following day, Peru responded by acknowledging the casus foederis.

Notes and references

Notes

References

- ↑ Basadre 1964, p. 2278

- 1 2 Crozier 1997

- ↑ Hugo Pereira Plascencia, La política salitrera del presidente Manuel Pardo

- ↑ Basadre 1964

- ↑ Bulnes 1920

- ↑ Jorge Basadre, "La guerra con Chile", version pdf of the UNJBG/UTI (Universidad Jorge Basadre), Capítulo Primero, page 37. This passage doesn't appeared in the book edition 1964

- ↑ Manuel Ravest Mora, La Casa Gibbs y el Monopolio Salitrero Peruano, 1876-1878, Historia N°41, vol. I, enero-junio 2008: 63-77, ISSN 0073-2435

- ↑ Querejazu Calvo 1979, p. 211

- ↑ Sater 2007, p. 29

- ↑ Collier, Simon (1996). A History of Chile, 1808-1994. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-56827-2.

- ↑ Sater 2007, p. 31

- ↑ Sater 2007, p. 32

Bibliography

- Basadre, Jorge (1964). Historia de la República del Perú, La guerra con Chile (in Spanish). Lima, Perú: Peruamerica S.A.,.

- Bulnes, Gonzalo (1920). Chile and Peru: the causes of the war of 1879. Santiago, Chile: Imprenta Universitaria.

- Contreras Carranza, Carlos (2012). La economía pública en el Perú después del guano y del salitre (in Spanish) (Primera ed.). Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos. ISBN 978-9972-51-349-7.

- Crozier, Ronald D. (1997). "El salitre hasta la Guerra del Pacífico, una revisión". Historia (history of the Americas journal) (in Spanish). Instituto de Historia, Pontifical Catholic University of Chile. 30: 53–126.

- Greenhill, Robert G.; Miller, Rory M. (1973). "The Peruvian Government and the Nitrate Trade, 1873-1879". Journal of Latin American Studies. 5: 107–131. doi:10.1017/S0022216X00002236.

- Gonzales Miranda, Sergio (2014). "El problema de la propiedad salitrera en Tarapacá durante la década de 1880" (in Spanish). pp. 39–64. doi:10.4067/S0717-71942014000100002. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- Ravest Mora, Manuel (1983). La compañía salitrera y la ocupación de Antofagasta 1878-1879 (in Spanish). Santiago de Chile: Editorial Andrés Bello.

- Ravest Mora, Manuel (2008). La Casa Gibbs y el monopolio salitrero peruano: 1876-1879. Historia, n° 41, enero-junio 2008, Pontifical Catholic University of Chile (in Spanish). 1. Santiago de Chile. pp. 63–67.

- Sater, William F. (2007). Andean Tragedy: Fighting the War of the Pacific, 1879–1884. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-4334-7.

- St John, Ronald Bruce (1992). Foreign Policy of Peru. Colorado, USA: Lynne Rienner Publishers, Inc. p. 105. ISBN 1-55587-304-9.

- Querejazu Calvo, Roberto (1979). Guano, Salitre y Sangre (in Spanish). La Paz-Cochabamba, Bolivia: Editorial los amigos del Libro.