Bristle-faced free-tailed bat

| Bristle-faced Free-tailed Bat Temporal range: Late Eocene to recent | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Chiroptera |

| Suborder: | Microchiroptera |

| Superfamily: | Molossoidea |

| Family: | Molossidae |

| Genus: | Mormopterus |

| Subgenus: | Setirostris |

| Species: | M. eleryi |

| Binomial name | |

| Mormopterus eleryi Reardon & McKenzie, 2008 | |

| |

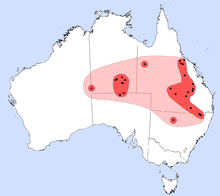

| Mormopterus eleryi range (2014) | |

The bristle-faced free-tailed bat (Mormopterus eleryi), previously known as the hairy-rostrum or hairy-nosed freetail bat, is a small insectivorous bat that is the only member of the molossid sub-genus Setirostris.[4] The bristle-faced free-tailed bat differs from all other bats in the Family Molossidae by possessing unique dentition, a distinctive echolocation call, diagnostic genital and glans penis morphology and small body size.[5] It is readily distinguished from other Mormopterus species by the presence of characteristic stout bristles on the muzzle and face.[6]

Taxonomy

A 1998 genetic study of species boundaries in Australian free-tailed bats (Family Mollossidae) indicated that the bristle-faced free-tailed bat (referred to as Mormopterus sp 6) was one of a group of eight distinct and unresolved genetic groups in the Australian Mormopterus.[7] Mormopterus sp 6 was genetically distinct from all other types, however only a single specimen from central Australia was included in the study.[7] Accumulation of additional specimens (n=24) in Museum collections and targeted trapping facilitated formal description of the bristle-faced free-tailed bat in 2008 on the basis of morphology, the results of allozyme electrophoresis and investigation of echolocation call characteristics.[5] Further resolution of the Australian Molossidae has shown that the bristle-faced free-tailed bat and the east-coast free-tailed bat (Mormopterus norfolkensis) are only distantly related to other Australian Mollosid taxa, and the differences between these two species and remaining taxa in the Mormopterus 'planiceps' group lead to the erection of three new subgenera in 2014.[4] These subgenera include Setirostris (Reardon, McKenzie & Adams 2014) for Mormopterus eleryi, Micronomus (Reardon, McKenzie & Adams 2014) for Mormopterus norfolkensis and Ozimops (Reardon, McKenzie & Adams 2014) for the remaining seven Australian taxa and several Indo-Papuan forms formerly in the planiceps group.[4] The subgeneric name Setirostris (seta + rostrum) refers to the characteristic bristles on the face of the bristle-faced free-tailed bat [4] and the specific name eleryi is for Elery Hamilton-Smith in recognition of contributions to bat research and conservation.[5]

Description

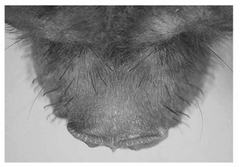

The bristle-faced free-tailed bat is distinctly small in size when compared to all other free-tailed bats, with a mean weight of 5.2 g (0.18 oz), a maximum weight of 8 g (0.28 oz) and a forearm length of 31.5 to 36 mm (1.24 to 1.42 in).[5][8] The face and muzzle is relatively long and narrow.[8] The ears are triangular, are not joined across the forehead and the tragus is rounded.[5] The muzzle and face are lightly haired with the exception of a unique series of 26 to 30 conspicuous bristles on each side and a fringe of fur on the upper lip.[5] The dorsal colour ranges from sandy-brown to grey-brown with lighter colouration on the ventral surface.[5][8]

A prominent long and slender genital projection is present in both male and female bristle-faced free-tailed bats.[5] The function of the projection remains unknown but these features are not shared by any other Australian Chiroptera [9] with the exception of Mormopterus norfolkensis.[5] Males of the bristle-faced free-tailed bat also possess unique serrated lateral flanges on the acutely pointed glans penis.[5][10] Features of the dentition of the bristle-faced free-tailed bat are also unique this species.[5]

Range and distribution

The bristle-faced free-tailed bat is uncommon and widely dispersed across broad areas of inland Australia, with specimens and records from central Australia and the remote south-western corner of the Northern Territory, northern South Australia, western and central Queensland and north western NSW.[5][8] The distribution of the bristle-faced free-tailed bat is unusual in that it ranges from extremely arid areas of the central Australian interior, where average annual rainfall is less than 200 mm (7.9 in), to areas of the north-eastern Queensland dry tropics where average annual rainfall can exceed 1,000 mm (39 in).[5] In the eastern component of its distribution the bristle-faced free-tailed bat occurs to the west of the Great Dividing Range within the Brigalow Belt (north and south), Mulga Lands, Darling Riverine Plains and Nandewar Biogeographic Regions.[5][11] In the western component of its distribution the bristle-faced free-tailed bat occurs within the Finke, MacDonnell Ranges, Simpson Strzelecki Dunefields and Central Ranges Bioregions.[5][11]

The presence of outlying records at Kaltukatjara (south-western Northern Territory), Mount Isa (north-western Queensland) and the area south of Bourke (north-western New South Wales) indicate that the bristle-faced free-tailed bat may have a greater distribution in the arid and semi-arid regions of NSW, Queensland, Northern Territory and Western Australia than available records indicate. However its range and status remain relatively poorly known. In 2008 it had been recorded at 26 localities[4] and few additional locations have been recorded in subsequent years.[12]

Habitat

Records of the bristle-faced free-tailed bat are predominantly individuals captured in mist nets or harp traps in riparian habitats on ephemeral streams, floodways, pools or dams, usually at sites supporting large fringing eucalypts.[5][6][8][12][13][14] Capture sites are consistently associated with riparian and floodplain habitats that support canopy eucalypts including Eucalyptus camaldulensis, Eucalyptus coolabah, Eucalyptus microtheca, Eucalyptus populnea, Eucalyptus polyanthemos and Eucalyptus citriodora.[5] At Gundabooka National Park in western NSW the bristle-faced free-tailed bat was only trapped along drainage lines with fringing Eucalyptus camaldulensis and Eucalyptus populnea.[13][15] During radio tracking studies at the Gundabooka site bristle-faced free-tailed bats were observed to preferentially forage along drainage lines and open channels, rarely moving into adjacent mulga vegetation, and all roost sites identified were in tall eucalypts within or adjacent to riparian zones.[13]

The preference of this species for riparian habitats is consistent across its known range. At the type locality in northern South Australia the bristle-faced free-tailed bat was captured on a floodway in Acacia cambagei low woodland with emergent Eucalyptus coolabah.[5] At Idalia National Park in western Queensland bristle-faced free-tailed bats (n=2) were captured in riparian woodland near open water, with canopy species including Eucalyptus camaldulensis and Eucalyptus populnea.[14] At a site in north-eastern NSW (Kwiambal National Park) the bristle-faced free-tailed bat was captured on a riparian terrace adjacent to a river, with canopy trees at the location including Eucalyptus camaldulensis, Eucalyptus blakelyi and Angophora floribunda.[12]

Behaviour and ecology

Information on the behaviour and ecology of the bristle-faced free-tailed bat is mainly derived from a short study conducted at Gundabooka National Park in western NSW in 2005.[13]

Roost sites

Bristle-faced free-tailed bats maintain diurnal roosts in the main trunk or branches of live or dead riparian eucalyptus trees.[13] All known roost sites (n=3) were in tall Eucalyptus populnea or Eucalyptus intertexta at a height of 3 to 6 m (9.8 to 19.7 ft) above the ground and displayed very small 13 to 20 mm (0.51 to 0.79 in) entrance holes leading to a larger chamber.[13] Diurnal roosts were shared with between four and twenty other bats (including bats of other species) and in some cases roosts are used on consecutive nights.[13] The roosts were located an average distance of 3.2 to 4 km (2.0 to 2.5 mi) from capture sites and females were found to occupy separate maternity roosts.[13]

Foraging and diet

Bristle-faced free-tailed bats emerge from their roosting sites and forage at night along drainage lines and open channels, flying with slow fluttering movements below the riparian canopy at 3 to 4 m (9.8 to 13.1 ft) in height.[13] Prey items (flying invertebrates) are captured in the air close to the ground or adjacent vegetation.[13] The specific composition of the invertebrate diet of the bristle-faced free-tailed bat is unknown.[8]

Echolocation

The echolocation call of the bristle-faced free-tailed bat contrasts with all other Australian molossid bats in that it displays a strongly frequency modulated search phase pulse.[5] The bristle-faced free-tailed bat also has the highest mean characteristic frequency (36 kHz) of any Australian Mormopterus.[13]

Reproduction

Information on the reproduction of the bristle-faced free-tailed bat is limited. A maternity roost located in December at Gundabooka National Park in western NSW contained a colony of 15 lactating females.[13] A female captured in the Northern Territory was in advanced pregnancy in October.[8]

Conservation status and threats

IUCN assessment and legislative status

The bristle-faced free-tailed bat has not been assessed by the IUCN (2014.2).[1] It is listed as endangered in NSW [2] and vulnerable in South Australia.[3] It is listed as a common or least concern species in the Northern Territory, Queensland and under Australian Commonwealth legislation.[5]

Population status

The bristle-faced free-tailed bat appears to be extremely rare across its range.[16] It has been detected at a limited number of localities and at these sites it appears to be uncommon, often comprising less than 2% of the bats captured during surveys.[5][13][14] In NSW it has only been recorded at a small number of locations despite recent extensive surveys at over 300 sites in suitable habitat.[16] Its preferred mode of foraging by flying at low levels along stream corridors suggests that the low numbers captured in surveys using mist nets and harp traps are an indication of rarity and are not an artifact of the survey methodology.[16] Long-term monitoring of known populations is required to determine changes in population status of the bristle-faced free-tailed bat.[17]

Threats

Identified and potential threats to populations of the bristle-faced free-tailed bat are related to the direct and indirect actions of humans (Homo sapiens), including land clearing,[16] timber harvesting, manipulation of water resources, altered fire regimes, use of pesticides, stocking with exotic ruminants, spread of feral animals and weeds [13] and atmospheric pollution leading to global warming.[18]

Key threatening processes

The most significant threat to the bristle-faced free-tailed bat is likely to be ongoing land clearing in semi-arid bioregions of Queensland and NSW.[16] The eastern Australian Bioregions that comprise the core range of the bristle-faced free-tailed bat, particularly the Brigalow Belt (north and south), have been subjected to broad scale clearing and habitat modification since European settlement.[19] Clearing of vegetation for agriculture and removal of hollow bearing trees for firewood collection and forestry are likely to reduce the availability of roosting sites for the bristle-faced free-tailed bat.[16] Clearing of native vegetation and removal of dead wood and dead trees have been recognised as key threatening processes for the bristle-faced free-tailed bat in NSW.[16]

Additional key threatening processes that are considered likely to impact the bristle-faced free-tailed bat include the alteration to natural flow regimes, competition from introduced western honey bees (Apis mellifera) for tree hollows, inappropriate fire regimes, reduction of invertebrate prey related to pesticide drift and lack of tree regeneration due to overgrazing and weeds.[13]

Anthropogenic climate change

Climate can influence bat distribution, movements and biogeography, access to food resources, timing of reproduction and emergence and rate of energy expenditure.[18][20] In combination with other factors, including ongoing loss and degradation of habitat, global climate change or global warming presents a serious and increasing threat to bats and other fauna.[18] The affinity of the bristle-faced free-tailed bat for riparian zones in arid and semi-arid environments renders it potentially vulnerable to the effects of water stress and extreme weather events.[18] Ecological factors that qualify the bristle-faced free-tailed bat as being at increased risk of the potential impacts of global climate change include habitat (species that rely on riparian habitats in water stress prone environments), foraging type (aerial hawking insectivore), roost type (tree hollow specialist), biogeography (species with limited dispersal ability, limited ranging behaviour) and extreme weather (species that occur in regions where there is an increasing risk of extreme temperature events or changes in rainfall patterns).[18]

Conservation reserves

The bristle-faced free-tailed bat has been recorded in a number of conservation reserves, including Gundabooka National Park (NSW),[13][15] Kwiambal National Park (NSW),[12] Dthinna Dthinnawan National Park (NSW),[12] Idalia National Park (QLD),[14] Mariala National Park (QLD) [5] and Witjira National Park (SA).[5] However the bioregions that are known to support bristle-faced free-tailed bat populations in the eastern component of its range, as well as a subset of bioregions where it occurs in central Australia, display very low rates of land area reserved for conservation (less than 5%).[21] Based on locality data [5][12][13] only 25% of sites known to support populations of bristle-faced free-tailed bats are protected within conservation reserves.

References

- 1 2 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2014.2 Accessed 19-09-2014. Mormopterus eleryi - not assessed.

- 1 2 , NSW Government (2014). Threatened Species Conservation Act 1995 Schedule 1: Endangered Species, Populations and Communities. Current version for 29 August 2014 to date (accessed 19 September 2014).

- 1 2 , Government of South Australia (2013). South Australia National Parks and Wildlife Act 1972 Version 16.5.2013. Schedule 8 - Vulnerable species.

- 1 2 3 4 5 , Reardon, T.B, McKenzie, N.L., Cooper, S. J. B., Appleton, B., Carthew, S. and Adams, M. (2014). A molecular and morphological investigation of species boundaries and phylogenetic relationships in Australian free-tailed bats Mormopterus (Chiroptera: Molossidae). Australian Journal of Zoology 62: 109–136.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 , Reardon, T.B., Adams. M., McKenzie, N.L. and Jenkins, P. (2008). A new species of Australian freetail bat Mormopterus eleryi sp. nov. (Chiroptera: Molossidae) and a taxonomic reappraisal of M. norfolkensis (Gray). Zootaxa 1875: 1–31.

- 1 2 Van Dyck, S., Gynther, I. and Baker, A. (eds) (2013). Field Companion to the Mammals of Australia. New Holland.

- 1 2 Adams. M., Reardon, T.B., Baverstock, P.R. and Watts, C.H.S. (1988). Electrophoretic resolution of species boundaries in Australian microchiroptera. IV. Molossidae (Chiroptera). Australian Journal of Biological Science 41: 315–26.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 , Churchill, S. (2009). Australian Bats. Second Edition. Allen and Unwin.

- ↑ Reardon, T.B. (2001). The unusual penis morphology of the hairy-nosed freetail bat. The Australasian Bat Society Newsletter 17: 53-54.

- ↑ , Reardon, T.B., McKenzie, N.L., Cooper, S.J.B., Appleton, B., Carthew, S. and Adams, M. (2014). A molecular and morphological investigation of species boundaries and phylogenetic relationships in Australian free-tailed bats Mormopterus (Chiroptera : Molossidae). Australian Journal of Zoology 62: 109–136.

- 1 2 , Commonwealth of Australia (2012). Interim Biorgeographic Regionalisation for Australia Version 7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 , Scotts, D. (2012). A record of the Bristle-faced free-tailed bat Mormopterus eleryi from Kwiambal National Park. Australian Zoologist 36: 49–54.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 , Pennay, M. (2006). Ecological Study of the Endangered Bristle-nosed Bat (Mormopterus species 6) and Survey of Microchiropteran Bats in Gundabooka National Park. Unpublished report, NSW National Parks & Wildlife Service Upper Darling Region.

- 1 2 3 4 , Young, R. A. and Ford, G. I. (2000). Bat fauna of a semi-arid environment in central western Queensland, Australia. Wildlife Research 27: 203–215.

- 1 2 , Ellis, M. (1998). The first record of the Hairy-nosed Freetail Bat in New South Wales. Australian Zoologist 31: 608–609.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 , Adam, P. (2004). Hairy-nosed Freetail Bat - endangered species listing. UNSW Scientific Committee - final determination.

- ↑ , OEH (2014). Bristle-faced free-tailed bat – Species Action Statement Priority Actions. Accessed 20 September 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Sherwin, H.A., Montgomery, W.I. and Lundy, M.J. (2012). The impact and implications of climate change for bats. Mammal Review 42: 171-183.

- ↑ , Seabrook, L., McAlpine, C., and Fensham, R. (2006). Cattle, crops and clearing: Regional drivers of landscape change in the Brigalow Belt, Queensland, Australia, 1840–2004. Landscape and Urban Planning 78: 373–385.

- ↑ Frick, W.F., Stepanian, P.M., Kelly, J.F., Howard, K.W., Kuster, C.M., Kunz, T.H. and Chilson, P.B. (2012). Climate and Weather Impact Timing of Emergence of Bats. PLoS ONE 7: e42737-e42737.

- ↑ , Natural Resource Management Ministerial Council (2010). Australia’s Strategy for the National Reserve System 2009–2030. Commonwealth of Australia.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mormopterus eleryi. |

- NSW Threatened Species Profile for Mormopterus eleryi

- NSW Scientific Committee Endangered species listing Mormopterus eleryi - final determination