The Call of the Wild

First edition cover | |

| Author | Jack London |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | Philip R. Goodwin and Charles Livingston Bull |

| Cover artist | Charles Edward Hooper |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Adventure fiction |

| Publisher | Macmillan |

Publication date | 1903 |

| Media type | Print (Serial, Hardcover & Paperback) |

| Pages | 231 pp (First Edition) |

| OCLC | 28228581 |

The Call of the Wild is a short adventure novel by Jack London published in 1903 and set in Yukon, Canada during the 1890s Klondike Gold Rush, when strong sled dogs were in high demand. The central character of the novel is a dog named Buck. The story opens at a ranch in Santa Clara Valley, California, when Buck is stolen from his home and sold into service as a sled dog in Alaska. He becomes progressively feral in the harsh environment, where he is forced to fight to survive and dominate other dogs. By the end, he sheds the veneer of civilization, and relies on primordial instinct and learned experience to emerge as a leader in the wild.

London spent almost a year in the Yukon collecting material for the book. The story was serialized in the Saturday Evening Post in the summer of 1903 and was published a month later in book form. The book’s great popularity and success made a reputation for London; much of its appeal derives from its simplicity as a tale of survival. As early as 1923, the story was adapted to film, and it has since seen several more cinematic adaptations.

Plot summary

The story opens with Buck, a large and powerful St. Bernard-Scotch Shepherd,[1][2] living happily in California's Santa Clara Valley as the pet of Judge Miller. He is stolen by the gardener's assistant, however, sold to fund the latter's gambling addiction, and shipped to Seattle. Put in a crate, he is starved and ill-treated. When released, he attacks the "man in the red sweater" but is badly beaten and taught to respect the "law of the club". Buck is then sold to a pair of French-Canadian dispatchers from the Canadian government, François and Perrault, who take him with them to the Klondike region of Canada. There, they train him as a sled dog. From his teammates, he quickly learns to survive cold winter nights and the pack society. A rivalry develops between Buck and the vicious, quarrelsome lead dog, Spitz. Buck eventually beats Spitz in a fight "to the death". Spitz is killed by the pack after his defeat by Buck, and Buck eventually becomes the leader of the team.

The team is then sold to a "Scottish half-breed" man working the mail service. The dogs must carry heavy loads to the mining areas, and the journeys they made were tiresome and long. One of the team, a morose husky named Dave, becomes sick and eventually has to be shot to end his misery.

Buck's next owners are a trio of stampeders (Hal, Charles, and a woman named Mercedes from the United States), who are inexperienced at surviving in the Northern wilderness. They struggle to control the sled and ignore warnings that the spring melt poses dangers. They overfeed the dogs and then starve them when the food runs out. On their journey they meet John Thornton, an experienced outdoorsman, who notices the dogs have been poorly treated and are in a weakened condition. He warns the trio against crossing the river, but they ignore his advice and order Buck to move on. Exhausted, starving, and sensing the danger ahead, Buck refuses and continues to lie unmoving in the snow. After Buck is beaten by Hal, Thornton recognizes him to be a remarkable dog. Disgusted by the driver's treatment of Buck, Thornton hits Hal with the butt of his axe, cuts Buck free from his traces, and tells the trio he is keeping him, much to Hal's displeasure. After some argument, the trio leaves and tries to cross the river, but as Thornton warned, the ice breaks, and the three fall into the river and drown, along with the sled and neglected dogs.

Buck comes to love and grow devoted to Thornton as he nurses him back to health. He saves Thornton when the man falls into a river. After Thornton takes him on trips to pan for gold, a bonanza king (someone who hit it rich in a certain area) wagers Thornton on the dog's strength and devotion. Buck wins by breaking a half-ton (1,000-pound (450 kg)) sled free of the frozen ground, pulling it 100 yards (91 m) and winning US$1,600 in gold dust. A king of the Skookum Benches offers a large sum to buy Buck, but Thornton has grown fond of him and declines.[3] While Thornton and his friends continue their search for gold, Buck explores the wilderness and socializes with a timber wolf from a local pack. One night, he returns from a long hunt to find that his beloved master and the others in the camp have been killed by a group of Yeehat natives. Buck eventually kills the natives to avenge Thornton, and he then is attacked by an entire pack of wolves. Buck wins the fight, then finds that the same timber wolf he had socialized with is in the pack he fought. Buck then follows the wolf and its pack into the forest, and answers the call of the wild. At the end of the story, Buck returns each year as the Ghost Dog of the Northland Legend, to mourn at the site of Thornton's death.

Background

California native Jack London had traveled around the United States as a hobo, returned to California to finish high school (he dropped out at age 14), and spent a year in college at Berkeley, when in 1897 he went to the Klondike by way of Alaska during the height of the Klondike Gold Rush. Later, he said of the experience: "It was in the Klondike I found myself."[4]

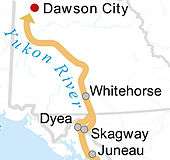

He left California in July and traveled by boat to Dyea, Alaska, where he landed and went inland. To reach the gold fields, he and his party transported their gear over the Chilkoot Pass, often carrying loads as heavy as 100 pounds (45 kg) on their backs. They were successful in staking claims to eight gold mines along the Stewart River.[5]

London stayed in the Klondike for almost a year, living temporarily in the frontier town of Dawson City, before moving to a nearby winter camp, where he spent the winter in a temporary shelter reading books he had brought: Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species and John Milton's Paradise Lost.[6] In the winter of 1898, Dawson City (today mostly deserted) was a city comprising about 30,000 miners, a saloon, an opera house, and a street of brothels.[7]

In the spring, as the annual gold stampeders began to stream in, London left. He had contracted scurvy, common in the Arctic winters where fresh produce was unavailable. When his gums began to swell he decided to return to California. With his companions, he rafted 2,000 miles (3,200 km) down the Yukon River, through portions of the wildest territory in the region, until they reached St. Michael. There, he hired himself out on a boat to earn return passage to San Francisco.[8]

In Alaska, London found the material that inspired him to write The Call of the Wild.[4] Dyea Beach was the primary point of arrival for miners when London traveled through there, but because its access was treacherous Skagway soon became the new arrival point for prospectors.[9] To reach the Klondike, miners had to navigate White Pass, known as "Dead Horse Pass", where horse carcasses littered the route because they could not survive the harsh and steep ascent. Horses were replaced with dogs as pack animals to transport material over the pass;[10] particularly strong dogs with thick fur were "much desired, scarce and high in price".[11]

London would have seen many dogs, especially prized Husky sled dogs, in Dawson City and in the winter camps situated close to the main sled route. He was friends with Marshall Latham Bond and his brother Louis Whitford Bond, the owners of a mixed St. Bernard-Scotch Collie dog about which London later wrote: "Yes, Buck is based on your dog at Dawson."[12] Beinecke Library at Yale University holds a photograph of Bond's dog, taken during London's stay in the Klondike in 1897. The depiction of the California ranch-style house in the beginning of the story was based on the Bond family ranch.[13]

Publication history

On his return to California, London was unable to find work and relied on odd jobs such as cutting grass. He submitted a query letter to the San Francisco Bulletin proposing a story about his Alaskan adventure, but the idea was rejected because, as the editor told him, "Interest in Alaska has subsided in an amazing degree."[8] A few years later, London wrote a short story about a dog named Bâtard who, at the end of the story, kills his master. London sold the piece to Cosmopolitan Magazine, which published it in the June 1902 issue under the title "Diablo — A Dog".[14] London's biographer, Earle Labor, says that London then began work on The Call of the Wild to "redeem the species" from his dark characterization of dogs in "Bâtard". Expecting to write a short story, London explains: "I meant it to be a companion to my other dog story "Bâtard" ... but it got away from me, and instead of 4,000 words it ran 32,000 before I could call a halt."[15]

Written as a frontier story about the gold rush, The Call of the Wild was meant for the pulp market. It was first published in four installments in The Saturday Evening Post, which bought it for $750 in 1903.[16][17] In the same year, London sold all rights to the story for $2,000 to Macmillan, which published it in book format.[17] The book has never been out of print since that time.[17]

Editions

- The first edition, by Macmillan, released in August 1903, had 10 tipped-in color plates by illustrators Philip R. Goodwin and Charles Livingston Bull, and a color frontispiece by Charles Edward Hooper; it sold for $1.50.[18][19] It is presently available with the original illustrations at the Internet Archive.[20]

Genre

.jpg)

The Call of the Wild falls into the genre of animal fiction, in which an animal is anthropomorphized and given human traits. In the story, London attributes human thoughts and insights to Buck, so much so that when the story was published he was accused of being a nature faker for attributing "unnatural" feelings to a dog.[21] Along with his contemporaries Frank Norris and Theodore Dreiser, London was influenced by the naturalism of European writers such as Émile Zola, in which themes such as heredity versus environment were explored. London's use of the genre gave it a new vibrancy, according to scholar Richard Lehan.[22]

The story is also an example of American pastoralism—a prevailing theme in American literature—in which the mythic hero returns to nature. As with other characters of American literature, such as Rip van Winkle and Huckleberry Finn, Buck symbolizes a reaction against industrialization and social convention with a return to nature. London presents the motif simply, clearly, and powerfully in the story, a motif later echoed by 20th century American writers William Faulkner and Ernest Hemingway (most notably in "Big Two-Hearted River").[23] Doctorow says of the story that it is "fervently American".[24]

The enduring appeal of the story, according to American literature scholar Donald Pizer, is that it is a combination of allegory, parable, and fable. The story incorporates elements of age-old animal fables, such as Aesop's Fables, in which animals speak truth, and traditional beast fables, in which the beast "substitutes wit for insight".[25] London was influenced by Rudyard Kipling's The Jungle Book, written a few years earlier, with its combination of parable and animal fable,[26] and by other animal stories popular in the early 20th century. In The Call of the Wild, London intensifies and adds layers of meaning that are lacking in these stories.[15]

As a writer London tended to skimp on form, according to biographer Labor, and neither The Call of the Wild nor White Fang "is a conventional novel".[27] The story follows the archetypal "myth of the hero"; Buck, who is the hero, takes a journey, is transformed, and achieves an apotheosis. The format of the story is divided into four distinct parts, according to Labor. In the first part, Buck experiences violence and struggles for survival; in the second part, he proves himself a leader of the pack; the third part brings him to his death (symbolically and almost literally); and in the fourth and final part, he undergoes rebirth.[28]

Themes

London's story is a tale of survival and a return to primitivism. Pizer writes that: "the strong, the shrewd, and the cunning shall prevail when ... life is bestial".[29]

Pizer also finds evident in the story a Christian theme of love and redemption, as shown by Buck's refusal to revert to violence until after the death of Thornton, who had won Buck's love and loyalty.[30] London, who went so far as to fight for custody of one of his own dogs, understood that loyalty between dogs (particularly working dogs) and their masters is built on trust and love.[31]

Writing in the "Introduction" to the Modern Library edition of The Call of the Wild, E. L. Doctorow says the theme is based on Darwin's concept of survival of the fittest. London places Buck in conflict with humans, in conflict with the other dogs, and in conflict with his environment—all of which he must challenge, survive, and conquer.[24] Buck, a domesticated dog, must call on his atavistic hereditary traits to survive; he must learn to be wild to become wild, according to Tina Gianquitto. He learns that in a world where the "club and the fang" are law, where the law of the pack rules and a good-natured dog such as Curly can be torn to pieces by pack members, that survival by whatever means is paramount.[32]

London also explores the question of "nature vs. nurture", according to Pizer. Buck, raised as a pet, is by heredity a wolf. The change of environment releases his innate characteristics and strengths to the point where he fights for survival and becomes leader of the pack. Furthermore, Pizer maintains that the story appeals to human nature with the theme of the strong prevailing, particularly when faced with harsh circumstances, and a return to the wild.[30]

The veneer of civilization is thin and fragile, writes Doctorow, and in the story London exposes the brutality at the core of humanity and the ease with which humans revert to a state of primitivism.[24] His interest in Marxism is evident in the sub-theme that humanity is motivated by materialism; and his interest in Nietzschean philosophy is shown by Buck's characterization.[24] Gianquitto writes that in Buck's characterization, London created a type of Nietschean Übermensch — in this case a dog that reaches mythic proportions.[33]

Doctorow sees the story as a caricature of a bildungsroman — in which a character learns and grows – in that Buck becomes progressively less civilized.[24] Gianquitto explains that Buck has evolved to the point that he is ready to join a wolf pack, which has a social structure uniquely adapted to and successful in the harsh arctic environment, unlike humans, who are weak in the harsh environment.[34]

Writing style

Old longings nomadic leap,

Chafing at custom’s chain;

Again from its brumal sleep

Wakens the ferine strain.

John Myers O'Hara, Atavism

The first chapter opens with the first quatrain of John Myers O'Hara's poem, Atavism,[35] published in 1902 in The Bookman. The stanza outlines one of the main motifs of The Call of the Wild: that Buck, when removed from the "sun-kissed" Santa Clara Valley where he was raised, will revert to his wolf heritage with its innate instincts and characteristics.[36]

The themes are conveyed through London's use of symbolism and imagery which, according to Labor, vary in the different phases of the story. The imagery and symbolism in the first phase, to do with the journey and self-discovery, depict physical violence, with strong images of pain and blood. In the second phase fatigue becomes a dominant image and death is a dominant symbol, as Buck comes close to being killed. The third phase is a period of renewal and rebirth and takes place in the spring, before ending with the fourth phase, when Buck fully reverts to nature is placed in a vast and "weird atmosphere", a place of pure emptiness.[37]

The setting is allegorical. The southern lands represent the soft, materialistic world; the north symbolizes a world beyond civilization and is inherently competitive.[30] The harshness, brutality, and emptiness in Alaska reduce life to its essence, as London learned, and shows in Buck's story. Buck must defeat Spitz, the dog who symbolically tries to get ahead and take control. When Buck is sold to Charles, Hal, and Mercedes, he finds himself in a camp that is dirty. They treat their dogs badly; they are artificial interlopers in the pristine landscape. Conversely, Buck's next masters, John Thornton and his two companions, are described as "living close to the earth". They keep a clean camp, treat their animals well, and represent man's nobility in nature.[23] Unlike Buck, Thornton loses his fight with his fellow species, and not until Thornton's death does Buck revert fully to the wild and his primordial state.[38]

The characters too are symbolic of types. Charles, Hal and Mercedes symbolize vanity and ignorance, while Thornton and his companions represent loyalty, purity, and love.[30] Much of the imagery is stark and simple with an emphasis on images of cold, snow, ice, darkness, meat, and blood.[38]

London varied his prose style to reflect the action. He wrote in an over-affected style in his descriptions of Charles, Hal, and Mercedes' camp as a reflection of their intrusion in the wilderness. Conversely when describing Buck and his actions, London wrote in a style that was pared down and simple—a style that would influence and be the forebear of Hemingway's style.[23]

The story was written as a frontier adventure and in such a way that it worked well as a serial. As Doctorow points out, it is good episodic writing that embodies the style of magazine adventure writing popular in that period. "It leaves us with satisfaction at its outcome, a story well and truly told," he said.[24]

Reception and legacy

.jpg)

The Call of the Wild was enormously popular from the moment it was published. H. L. Menken wrote of London's story: "No other popular writer of his time did any better writing than you will find in Call of the Wild."[4] A reviewer for The New York Times wrote of it in 1903: "If nothing else makes Mr. London's book popular, it ought to be rendered so by the complete way in which it will satisfy the love of dog fights apparently inherent in every man."[39] The reviewer for The Atlantic Monthly wrote that it was a book: "untouched by bookishness...The making and the achievement of such a hero [Buck] constitute, not a pretty story at all, but a very powerful one."[40]

The book secured London a place in the canon of American literature.[33] The first printing of 10,000 copies sold out immediately; it is still one of the best known stories written by an American author, and continues to be read and taught in schools.[24][41] It has been published in 47 languages.[42] London's first success, the book secured his prospects as a writer and gained him a readership that stayed with him throughout his career.[24][33]

After the success of The Call of the Wild London wrote to Macmillan in 1904 proposing a second book (White Fang) in which he wanted to describe the opposite of Buck: a dog that transforms from wild to tame: "I'm going to reverse the process...Instead of devolution of decivilization ... I'm going to give the evolution, the civilization of a dog."[43]

The first adaptation of London's story was a silent film made in 1923.[44] The 1935 version starring Clark Gable and Loretta Young expanded John Thornton's role and was the first "talkie" to feature the story. The 1972 movie The Call of the Wild, starring Charlton Heston as John Thornton, was filmed in Finland.[45]

References

- ↑ London 1998, p. 4.

- ↑ London 1903, Chapter 1.

- ↑ London 1903, Chapter 7.

- 1 2 3 "Jack London" 1998, p. vi.

- ↑ Courbier-Tavenier, p. 240.

- ↑ Courbier-Tavenier, p. 240–241.

- ↑ Dyer, p. 60.

- 1 2 Labor & Reesman, pp. 16–17.

- ↑ Giantquitto, 'Endnotes', pp. 294–295.

- ↑ Dyer, p. 59.

- ↑ "Comments and Questions", p. 301.

- ↑ Courbier-Tavenier, p. 242.

- ↑ Doon.

- ↑ Labor & Reesman, pp. 39–40.

- 1 2 Labor & Reesman, p. 40.

- ↑ Doctorow, p. xi.

- 1 2 3 Dyer, p. 61.

- ↑ Smith, p. 409.

- ↑ Leypoldt, p. 201.

- ↑ London, Jack & Goodwin, Philip R. (Illustrator) & Bull, Charles Livingston (Illustrator) (1903). The Call of the Wild (First ed.). MacMillan.

- ↑ Pizer, pp. 108–109.

- ↑ Lehan, p. 47.

- 1 2 3 Benoit, p. 246–248.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Doctorow, p. xv.

- ↑ Pizer, p. 107.

- ↑ Pizer, p. 108.

- ↑ Labor & Reesman, p. 38.

- ↑ Labor & Reesman, pp. 41–46.

- ↑ Pizer, p. 110.

- 1 2 3 4 Pizer, pp. 109–110.

- ↑ Giantquitto, 'Introduction', p. xxiv.

- ↑ Giantquitto, 'Introduction', p. xvii.

- 1 2 3 Giantquitto, 'Introduction', p. xiii.

- ↑ Giantquitto, 'Introduction', pp. xx–xxi.

- ↑ London 1998, p. 3.

- ↑ Giantquitto, 'Endnotes', p. 293.

- ↑ Labor & Reesman, pp. 41–45.

- 1 2 Doctorow, p. xiv.

- ↑ "Comments and Questions", p. 302.

- ↑ "Comments and Questions", pp. 302–303.

- ↑ Giantquitto, 'Introduction', p. xxii.

- ↑ WorldCat.

- ↑ Labor & Reesman, p. 46.

- ↑ "Call of the Wild, 1923". Silent Hollywood.com.

- ↑ "Inspired", p. 298.

Bibliography

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Benoit, Raymond (Summer 1968). "Jack London's 'The Call of the Wild'". American Quarterly. The Johns Hopkins University Press. 20 (2): 246–248. doi:10.2307/2711035. JSTOR 2711035.

- Courbier-Tavenier, Jacqueline (1999). "The Call of the Wild and The Jungle: Jack London and Upton Sinclair's Animal and Human Jungles". In Pizer, Donald. Cambridge Companion to American Realism and Naturalism: Howells to London. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-43876-6.

- Doctorow, E. L.; London, Jack (1998). "Introduction". The Call of the Wild, White Fang & To Build a Fire. The Modern Library hundred best novels of the twentieth century. 88 (reprint ed.). Modern Library. ISBN 978-0-375-75251-3. OCLC 38884558.

- Doon, Ellen. "Marshall Bond Papers". New Haven, Conn, USA: Yale University. Retrieved March 19, 2012.

- Dyer, Daniel (April 1988). "Answering the Call of the Wild". The English Journal. National Council of Teachers of English. 77 (4): 57–62. doi:10.2307/819308. JSTOR 819308.

- Barnes & Noble (2003). " 'Jack London' — Biographical Note". The Call of the Wild and White Fang. Barnes and Noble Classics. Introduction by Tina Giantquitto (reprint ed.). Barnes & Noble. ISBN 978-1-59308-002-0.

- Barnes & Noble (2003). " 'The World of Jack London'". The Call of the Wild and White Fang. Barnes and Noble Classics. Introduction by Tina Giantquitto (reprint ed.). Barnes & Noble. ISBN 978-1-59308-002-0.

- Giantquitto, Tina (2003). " 'Introduction'". The Call of the Wild and White Fang. Barnes and Noble Classics. Introduction by Tina Giantquitto (reprint ed.). Barnes & Noble. ISBN 978-1-59308-002-0.

- Giantquitto, Tina (2003). " 'Endnotes'". The Call of the Wild and White Fang. Barnes and Noble Classics. Introduction by Tina Giantquitto (reprint ed.). Barnes & Noble. ISBN 978-1-59308-002-0.

- Barnes & Noble (2003). " Inspired by 'The Call of the Wild' and 'White Fang'". The Call of the Wild and White Fang. Barnes and Noble Classics. Introduction by Tina Giantquitto (reprint ed.). Barnes & Noble. ISBN 978-1-59308-002-0.

- Barnes & Noble (2003). " 'Comments and Questions'". The Call of the Wild and White Fang. Barnes and Noble Classics. Introduction by Tina Giantquitto (reprint ed.). Barnes & Noble. ISBN 978-1-59308-002-0.

- Lehan, Richard (1999). "The European Background". In Pizer, Donald. Cambridge Companion to American Realism and Naturalism: Howells to London. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-43876-6.

- "Jack London's 'The Call of the Wild' ". Publishers Weekly. F. Leypoldt. 64 (1). August 1, 1903. Retrieved August 28, 2012.

- Labor, Earle; Reesman, Jeanne Campbell (1994). Jack London. Twayne's United States authors series. 230 (revised, illustrated ed.). New York: Twayne Publishers. ISBN 978-0-8057-4033-2. OCLC 485895575.

- London, Jack (1903). The Call of the Wild. Wikisource.

- London, Jack (1998). The Call of the Wild, White Fang & To Build a Fire. The Modern Library hundred best novels of the twentieth century. 88. Introduction by E. L. Doctorow (reprint ed.). Modern Library. ISBN 978-0-375-75251-3. OCLC 38884558.

- Modern Library (1998). " 'Jack London' — Biographical Note". The Call of the Wild, White Fang & To Build a Fire. The Modern Library hundred best novels of the twentieth century. 88. Introduction by E. L. Doctorow (reprint ed.). Modern Library. ISBN 978-0-375-75251-3. OCLC 38884558.

- Pizer, Donald (1983). "Jack London: The Problem of Form". Studies in the Literary Imagination. 16 (2): 107–115.

- Smith, Geoffrey D. (August 13, 1997). American Fiction, 1901–1925: A Bibliography. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-43469-0. Retrieved August 28, 2012.

- "London, Jack 1876–1916". The call of the wild. WorldCat. Retrieved October 26, 2012.

Further reading

- Fusco, Richard. "On Primitivism in The Call of the Wild. American Literary Realism, 1870-1910. Vol. 20, No. 1 (Fall, 1987), pp. 76–80

- McCrum, Robert. "The 100 best novels: No 35 - The Call of the Wild by Jack London (1903)". The Guardian. 19 May 2014. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

External links

The Call of the Wild public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Call of the Wild public domain audiobook at LibriVox- The Call of the Wild ePub/Mobi version