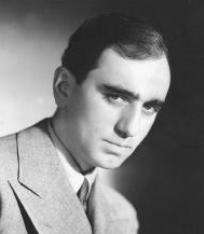

Busby Berkeley

| Busby Berkeley | |

|---|---|

(c.1935) | |

| Born |

Berkeley William Enos November 29, 1895 Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Died |

March 14, 1976 (aged 80) Palm Desert, California, U.S. |

| Resting place | Desert Memorial Park, Cathedral City, California |

| Occupation | film director, choreographer |

| Years active | 1901–1971 |

Busby Berkeley (born Berkeley William Enos; November 29, 1895 – March 14, 1976)[1] was a Hollywood movie director and musical choreographer.

Berkeley devised elaborate musical production numbers that often involved complex geometric patterns. Berkeley's works used large numbers of showgirls and props as fantasy elements in kaleidoscopic on-screen performances.

Early life and career

Berkeley was born in Los Angeles, California, to stage actress Gertrude Berkeley. Among Gertrude's friends, and a performer in Tim Frawly's Stock company run by Busby Berkeley's father Francis Enos (who died when Busby was eight), were actress Amy Busby from which Berkeley gained the appellation "Buzz" or Busby"[2][3] and actor William Gillette, then only four years away from playing Sherlock Holmes. Whether he was actually christened Busby Berkeley William Enos,[4] or Berkeley William Enos, with "Busby" being a nickname, is not unanimous[2][5] – the "Child's names" entry on his birth certificate is blank.[4]

In addition to her stage work, Gertrude played mother roles in silent films while Berkeley was still a child. Berkeley made his stage début at five, acting in the company of his performing family. During World War I, Berkeley served as a field artillery lieutenant. Watching soldiers drill may have inspired his later complex choreography. During the 1920s, Berkeley was a dance director for nearly two dozen Broadway musicals, including such hits as A Connecticut Yankee. As a choreographer, Berkeley was less concerned with the terpsichorean skill of his chorus girls as he was with their ability to form themselves into attractive geometric patterns. His musical numbers were among the largest and best-regimented on Broadway.

His earliest film work was in Samuel Goldwyn's Eddie Cantor musicals, where he began developing such techniques as a "parade of faces" (individualizing each chorus girl with a loving close-up), and moving his dancers all over the stage (and often beyond) in as many kaleidoscopic patterns as possible. Berkeley's top shot technique (the kaleidoscope again, this time shot from overhead) appeared seminally in the Cantor films, and also the 1932 Universal drama film Night World (where he choreographed the number "Who's Your Little Who-Zis?"). His numbers were known for starting out in the realm of the stage, but quickly exceeding this space by moving into a time and place that could only be cinematic, only to return to shots of an applauding audience and the fall of a curtain. As choreographer, Berkeley was allowed a certain degree of independence in his direction of musical numbers, and they were often markedly distinct from (and sometimes in contrast to) the narrative sections of the films. The numbers he choreographed were mostly upbeat and focused on decoration as opposed to substance; one exception to this is the number "Remember My Forgotten Man" from Gold Diggers of 1933, which dealt with the treatment of World War I veterans during The Great Depression.

Berkeley's popularity with an entertainment-hungry Great Depression audience was secured when he choreographed four musicals back-to-back for Warner Bros.: 42nd Street, Footlight Parade, the aforementioned Gold Diggers of 1933 and Fashions of 1934, as well as In Caliente and Wonder Bar with Dolores del Río. Berkeley's innovative and often sexually charged dance numbers have been analyzed at length by cinema scholars. In particular, the numbers have been critiqued for their display (and some say exploitation) of the female form as seen through the "male gaze", and for their depiction of collectivism (as opposed to traditionally American rugged individualism) in the spirit of Roosevelt's New Deal. Berkeley always denied any deep significance to his work, arguing that his main professional goals were to constantly top himself and to never repeat his past accomplishments.

As the outsized musicals in which Berkeley specialized became passé, he turned to straight directing. The result was 1939's They Made Me a Criminal, one of John Garfield's best films. Berkeley had several well-publicized run-ins with MGM stars such as Judy Garland. In 1943, he was removed as director of Girl Crazy because of disagreements with Garland, although the lavish musical number "I Got Rhythm", which he directed, remained in the picture.[6]

.jpg)

His next stop was at 20th Century-Fox for 1943's The Gang's All Here, in which Berkeley choreographed Carmen Miranda's "Lady in the Tutti-Frutti Hat" number. The film made money, but Berkeley and the Fox brass disagreed over budget matters. Berkeley returned to MGM in the late 1940s, where among many other accomplishments he conceived the Technicolor finales for the studio's Esther Williams films. Berkeley's final film as choreographer was MGM's Billy Rose's Jumbo (1962).

Later career

In the late 1960s, the camp craze brought the Berkeley musicals back to the forefront. He toured the college and lecture circuit, and even directed a 1930s-style cold medication commercial, complete with a top shot of a dancing clock. In his 75th year, Berkeley returned to Broadway to direct a successful revival of No No Nanette starring his old Warner Brothers colleague and "42nd Street" star Ruby Keeler; both also played cameos in the 1970 film The Phynx the same year.

Berkeley was inducted into the National Museum of Dance's Mr. & Mrs. Cornelius Vanderbilt Whitney Hall of Fame in 1988.

Personal life

Berkeley was married six times[7] and was survived by his wife Etta Dunn. He was also involved in an alienation of affections lawsuit in 1938 involving Carole Landis.[8] In September 1935, Berkeley was the driver responsible for an automobile accident in which two people were killed, five seriously injured; Berkeley himself was badly cut and bruised.[9] Berkeley, brought to court on a stretcher,[10] heard testimony that Time magazine said made him wince:[9]

- 'Witnesses testified that motorist Berkeley sped down Roosevelt Highway in Los Angeles County one night, changed lanes, crashing headlong into one car, sideswiped another. Some witnesses said they smelled liquor on him'.[9]

After the first two trials for second degree murder ended with hung juries, he was acquitted in a third trial.

Berkeley died on March 14, 1976 in Palm Springs, California at the age of 80 from natural causes.[11] He is buried in the Desert Memorial Park in Cathedral City, California.[1][12]

Broadway credits

- A Connecticut Yankee (1927) (choreographer)

- Whoopee! (1928) (choreographer)

- No, No, Nanette (1971) (production supervisor)

Partial filmography

- Whoopee! (1930) (choreographer)

- Kiki (1931) (choreographer)

- Palmy Days (1931) (choreographer)

- Flying High (1931) (choreographer)

- The Kid from Spain (1932) (choreographer)

- Night World (1932) (choreographer)

- She Had to Say Yes, 1933) (directorial debut)

- 42nd Street (1933) (choreographer)

- Gold Diggers of 1933 (1933) (choreographer)

- Footlight Parade (1933) (choreographer)

- Roman Scandals (1933) (choreographer)

- Fashions of 1934 (1934) (director/choreographer of musical numbers)

- Wonder Bar (1934) (designer of musical numbers)

- Dames (1934) (director/choreographer of musical numbers)

- Gold Diggers of 1935 (1935) (director/also created and staged dances)

- In Caliente (1935) (director/choreographer of musical numbers)

- I Live for Love (1935) (director)

- Gold Diggers of 1937 (1936) (director/choreographer of musical numbers)

- Stage Struck (1936) (director)

- The Go Getter (1937) (director)

- The Singing Marine (1937) (director/choreographer of musical numbers)

- Hollywood Hotel (1937) (director)

- Varsity Show (1937) (director of finale)

- Gold Diggers in Paris (1938) (director/choreographer of musical numbers)

- Men Are Such Fools (1938) (director)

- Comet Over Broadway (1938) (director, replaced by John Farrow)

- They Made Me a Criminal (1939) (director)

- Fast and Furious (1939) (director)

- Broadway Serenade (1939) (director of finale)

- The Wizard of Oz (1939) (director of deleted "If I Only Had a Brain" dance)

- Babes in Arms (1939) (director)

- Strike Up the Band (1940) (director)

- Forty Little Mothers (1940) (director)

- Ziegfeld Girl (1941) (director of musical numbers)

- Babes on Broadway (1941) (director)

- Lady Be Good (1941) (director of musical numbers)

- For Me and My Gal (1942) (director)

- Cabin in the Sky (1943) (director of "Shine" sequence)

- Girl Crazy (1943) (director of "I Got Rhythm" finale)

- The Gang's All Here (1943) (director)

- Cinderella Jones (1946) (director)

- Romance on the High Seas (1948) (choreographer)

- Take Me Out to the Ball Game (1949) (director)

- Annie Get Your Gun (1950) (uncredited director)

- Two Weeks with Love (1950) (choreographer)

- Call Me Mister (1951) (choreographer)

- Two Tickets to Broadway (1951) (choreographer)

- Million Dollar Mermaid (1952) (choreographer)

- Small Town Girl (1953) (choreographer)

- Easy to Love (1953) (choreographer)

- Rose Marie (1954) (choreographer)

- Billy Rose's Jumbo (1962) (choreographer)

See also

References

- 1 2 Palm Springs Cemetery District, "Interments of Interest"

- 1 2 Joseph F. Clarke (1977). Pseudonyms. BCA. p. 112.

- ↑ Amy Busby portrait gallery; New York Public Library Retrieved April 28, 2015

- 1 2 Spivak, Jeffrey, Buzz, The Life and Art of Busby Berkeley (University Press of Kentucky, 2010), pp. 6-7.

- ↑ "Busby Berkeley – Hollywood's Golden Age".

- ↑ Hugh Fordin, The World of Entertainment: The Freed Unit at MGM, 1975

- ↑ Hanley, Robert (1976). "Busby Berkeley, the Dance Director, Dies", in the New York Times, March 15, 1976, p. 33

- ↑ Fleming, E.J. (2005). Carole Landis: A Tragic Life in Hollywood. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland and Co. ISBN 978-0-7864-2200-5, p. 49

- 1 2 3 People, Sep. 30, 1935, from Time magazine

- ↑ Choreographer and film director Busby Berkeley being carried into his manslaughter trial on a stretcher, a Los Angeles Times photo from the website of the UCLA Charles E. Young Research Library

- ↑ Johns, Howard, (2004). Palm Springs Confidential: Playground of the Stars. Fort Lee, New Jersey: Barricade Books. ISBN 1-56980-297-1

- ↑ Brooks, Patricia; Brooks, Jonathan (2006). "Chapter 8: East L.A. and the Desert". Laid to Rest in California: a guide to the cemeteries and grave sites of the rich and famous. Guilford, CT: Globe Pequot Press. pp. 240–2. ISBN 978-0-7627-4101-4. OCLC 70284362.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Busby Berkeley. |

- Busby Berkeley at the Internet Broadway Database

- Busby Berkeley at the Internet Movie Database

- Busby Berkeley at the TCM Movie Database

- Busby Berkeley at AllMovie

- Kit and Morgan Benson (January 1, 2001). "Busby Berkeley". Motion picture director. Find a Grave. Retrieved June 29, 2011.

- Hooray for Hollywood: Busby Berkeley

- Busby Berkeley at Classic Movie Favorites Tribute site: galleries, bio, filmography and more.

- bio & pics on Busby Berkeley