California Southern Railroad

|

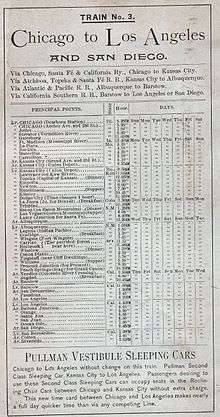

Route map of the California Southern Railroad upon its completion in 1885. | |

| Locale | San Diego – Barstow, California |

|---|---|

| Dates of operation | 1880–1889 |

| Successor | Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge |

| Headquarters | National City, California |

The California Southern Railroad was a subsidiary railroad of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway (Santa Fe) in Southern California. It was organized July 10, 1880, and chartered on October 23, 1880, to build a rail connection between what has become the city of Barstow and San Diego, California.[1]

Construction began in National City, just south of San Diego, in 1881, and proceeded northward to the present day city of Oceanside. From there, the line turned to the northeast through Temecula Canyon, then on to the present cities of Lake Elsinore, Perris and Riverside before a connection to the Southern Pacific Railroad (SP) in Colton. Following a frog war where the SP refused to let the California Southern cross its tracks, a dispute that was resolved by court order in favor of the California Southern, construction continued northward through Cajon Pass to the present day cities of Victorville and Barstow. The line, completed on November 9, 1885, formed the western end of Santa Fe's transcontinental railroad connection to Chicago. Portions of the original line are still in use today as some of the busiest rail freight and passenger routes in the United States.

History

The California Southern was organized on July 10, 1880, as a means to connect San Diego to a connection with the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad at an as-yet undetermined point. Among the organizers were Frank Kimball, a prominent landowner and rancher from San Diego who also represented the Chamber of Commerce and the Board of City Trustees of San Diego, Kidder, Peabody & Co., one of the main financial investment companies involved in the Santa Fe, B.P. Cheney, L.G. Pratt, George B. Wilbur and Thomas Nickerson who was president of the Santa Fe. The organizers set a deadline of January 1, 1884, to complete the connection, a deadline that was later adjusted due to problems in the construction of the Atlantic and Pacific that forced it to stop at Needles, California.[2]

The California Southern built its track northward from a point in National City, south of San Diego. The route, portions of which are still in use, connected the present day cities of National City, San Diego, Fallbrook, Temecula, Lake Elsinore, Perris, Riverside, San Bernardino, Colton, Cajon (not to be confused with El Cajon), Victorville and Barstow.

In Barstow, then known as Waterman, the California Southern would connect to another Santa Fe subsidiary, the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad. The Atlantic and Pacific was chartered in 1866 to build a railroad connection westward from Springfield, Missouri, connecting Albuquerque, New Mexico, then along the 35th parallel to the Colorado River. From there, the railroad was to continue to the Pacific Ocean following whatever proved to be the best route. The route was scheduled to be completed by July 4, 1878.[3] However, the Southern Pacific was able to get a clause favorable to their own interests inserted into the charter:

- "... the Southern Pacific Railroad ... is hereby authorized to connect with the said Atlantic and Pacific railroad formed under this act, at such point, near the boundary line of the State of California, as they shall deem most suitable for a railroad line to San Francisco."[4]

Southern Pacific had already established a connection to Mojave, so their crews built eastward from there through Barstow (then called Waterman) to Needles, California, completing the connection across the Colorado River on August 3, 1883.[5] The California segment was leased to the Santa Fe in August 1884,[6] and fully acquired by the Santa Fe under foreclosure in 1897.

San Diego

The California Southern began construction in National City on land originally acquired by Frank Kimball. The railroad's main yards and locomotive maintenance shops were located here, and until the connection was made with Barstow, all tools and equipment ordered by the railroad arrived here by ship around Cape Horn from points in the eastern United States, while the wooden ties arrived by ship from Oregon.[7] Surveys and construction between National City and San Diego were well underway by March 1881. The railroad reached Fallbrook and opened between there and San Diego in January 1882.[8]

In 1881 and 1882, the California Southern received ten locomotive shipments by sea at National City. The last three of these, delivered in November 1882 aboard the ship Anna Camp, have been identified as the last three locomotives ever delivered to the United States Pacific coast after traveling around Cape Horn.[9]

Temecula Canyon

To connect to the Atlantic and Pacific line in the quickest way possible, surveyors and engineers for the California Southern pushed the route through Fallbrook and Temecula—bypassing what was, at the time, the pueblo of Los Angeles. The railroad, however, didn't understand the nature of Southern California's dry washes. Local inhabitants warned the railroad of the dangers of building through such an area, that it could become a raging torrent of water, but the railroad built through the canyon anyway.[10]

Despite the warnings, track work through the canyon proceeded at a quick pace. They completed the line to Fallbrook on January 2, 1882, then to Temecula on March 27, 1882.[11]

Many parts of the canyon had suffered storms. In February 1884, a storm hit. The train was delayed and the canyon walls brought boulders crashing down on the rails. On February 3, the train was unable to get through. A few days later, the wires were down. The train from Colton to San Diego could not get through. Disaster was averted because a local resident, Charlie Howell, hurried up the tracks from his family homestead near Willow Glen and managed to stop the train.[12] A series of devastating washouts on the section through Temecula Canyon occurred amid heavy rain storms that flooded the area starting on February 16, 1884, just six months after the first trains operated the entire route between San Diego and San Bernardino. The storms brought more than 40 inches (1,000 mm) of rain in a four-week period. Two thirds of the mainline through the canyon were washed out with ties seen floating as far as 80 miles (129 km) away in the ocean.[13] Temporary track repairs were made after the first storms, but later in the month, additional rains and flooding washed out the entire route through the canyon. Repairs were estimated at nearly $320,000, a figure that could not be recouped effectively.[6]

The canyon was finally bypassed completely with the completion of the Surf Line on August 12, 1888, and the line through the canyon was relegated to branch line status.[14] By 1900 it had been abandoned by AT&SF. Finally, the 1928 construction of Railroad Canyon Dam submerged the section of track between Elsinore and Perris beneath Railroad Canyon Lake (now known as Canyon Lake).

The crossing at Colton

Construction of the California Southern was repeatedly interrupted by Santa Fe's rival, Southern Pacific Railroad (SP). In one instance, the California Southern was set to build a level junction across the SP tracks in Colton, a move that would end Southern Pacific's monopoly in Southern California.[15]

The Colton Crossing was the site of one of the more notable frog wars in American railroad history. In the summer of 1882, tensions reached their boiling point when construction of tracks for the California Southern reached Colton, California. In an attempt to forcibly prevent the California Southern Railroad crews from completing construction, the Southern Pacific (SP) parked and then slowly moved a locomotive and gondola along the SP track at the location of the planned crossing. In addition, the SP hired armed men, including the famous Virgil Earp, to guard the tracks. Before the violence could get out of hand, Governor Robert Waterman ordered San Bernardino County Sheriff J.B. Burkhart to enforce the state court order. Waterman personally ordered Earp and the crowd to comply with the court order. Earp backed down and told the SP engineer to move the locomotive. The crossing was built, ending the Southern Pacific's monopoly in Southern California.[15][16][17]

Cajon Pass

The first structure that the California Southern used as a depot in San Bernardino was a converted boxcar.[18] Building north from San Bernardino, the California Southern was able to piggyback on the survey work done by the Los Angeles and Independence Railroad up to a point near Cajon.[11]

The original grade of the line up the pass rose at a 2.2% slope between San Bernardino and Cajon, where the grade steepened to 3% until reaching the summit 6 miles (9.7 km) further.[19] The route over Cajon Pass was completed with a "last spike" on November 9, 1885,[20] and the first train to use the pass carried a load of rails southward from Barstow on November 12 to be installed near Riverside.[21] The first through train from Chicago via Santa Fe lines arrived in San Diego on November 17, 1885.[22]

Construction of the original route through Cajon Pass was overseen by Jacob Nash Victor, who by this time had become General Manager of the California Southern. He operated the first train through the pass in 1885, proclaiming "No other railroad will ever have the nerve to build through these mountains. All who follow will prefer to rent trackage from us." Victor's assertion remained true for a while as the San Pedro, Los Angeles and Salt Lake Railroad (which later became part of Union Pacific Railroad) signed an agreement to operate over the California Southern track via trackage rights on April 26, 1905,[23] but Victor was proven wrong eighty years later when SP built the Palmdale Cutoff in 1967 at a slightly higher elevation through the pass.[24] In honor of his work through the pass, the city of Victorville was named after Victor.[25]

Consolidation

To reach Los Angeles, the Santa Fe leased trackage rights over the Southern Pacific from San Bernardino on November 29, 1885, at $1,200 per mile per year.[21] Naturally, the Santa Fe sought ways to reduce the fees. On November 20, 1886, the Santa Fe incorporated the San Bernardino and Los Angeles Railway to build a rail connection between its namesake cities. California Southern track crews performed the construction work, and the first train on the new line arrived in Los Angeles on May 31, 1887.

During construction, Santa Fe officials worked to consolidate the many subsidiary railroads in Southern California to reduce costs. At a stockholder meeting on April 23, the eight railroads and their prominent stockholders, minus the California Southern, voted in favor of consolidation, and the California Central Railway was formed as a result on May 20, 1887. After the consolidation, although the California Southern remained a separate subsidiary, the National City shops were downgraded and the services provided there were moved to the newly constructed shops in San Bernardino.[26] One of the first official lists of stations on the California Southern and California Central railroads published on July 13, 1887, shows the California Southern divided operationally into two divisions: the San Diego division covered the territory between National City and Colton; from there, the San Bernardino Division covered the route through Cajon Pass to Barstow.[27]

The Santa Fe underwent a massive financial overhaul in 1889. The major investors in Boston, Massachusetts, were mostly replaced by investors from New York and London at the annual meeting on May 9. The investors replaced the company's board of directors with a new board that included George C. Magoun (who would later be linked with the company's 1893 receivership). The new investors disliked the number of subsidiary companies and sought to further consolidate them. The California Southern, California Central and Redondo Beach Railway companies were consolidated into the Southern California Railway on November 7, 1889.[28] The California Central had consolidated with the Los Angeles and San Gabriel Valley Railroad in 1887, giving it ROW through the San Gabriel Valley. The Santa Fe finally purchased outright the holdings of the Southern California railroad on January 17, 1906, ending the railway's subsidiary status and making it fully a part of the Santa Fe railroad.[29][30]

Company officers

Presidents of the California Southern Railroad were:

- Benjamin Kimball 1880

- Thomas Nickerson 1880-1885

- George B. Wilbur 1885-1887

- George O. Manchester 1887-__[31][32]

Visible remnants

Much of the right-of-way graded and used by the California Southern is still in use. Several structures built for or by the railroad, or in some cases their remains, can still be seen. Some of the buildings that remain are still in use in their primary purposes.

The two ends of the former railroad are still in use as of 2013. The section between Barstow and Riverside through Cajon Pass, which includes the disputed crossing in Colton, remains one of the busiest rail freight corridors in the United States, seeing trains of BNSF Railway and Union Pacific Railroad as well as Amtrak's daily Southwest Chief passenger train. At Cajon the concrete pads that served as the foundations for the railroad's station facilities and water tanks there remain long after the buildings atop them were removed. The Santa Fe realigned the track at several places during the 20th century to straighten curves along Cajon Creek (between Cajon and San Bernardino), lower grades for eastbound trains with the 1913 addition of a separate track through what has come to be known as Sullivan's Curve, and to reduce some curvature and lower the pass's summit elevation by 50 ft (15 m).

The maintenance shops in San Bernardino are still in use by BNSF Railway, although not to the extent that they were used in the 20th century. The San Bernardino station that was opened by the California Southern was destroyed by fire on November 16, 1916.[33] It was replaced in 1918[34] by the Santa Fe with the current structure that now serves Metrolink's San Bernardino Line commuter trains on runs that terminate at Los Angeles Union Station. Until the introduction of weekend service on the 91 Line in July 2014, limited service from San Bernardino to Riverside was provided by some San Bernardino Line trains, and the Metrolink Riverside Line terminates at the Riverside station although it reaches the station via a more southerly route. South of Riverside the track is still in place to Perris, where the Orange Empire Railway Museum has a connection to the mainline. This section is being rehabilitated to the Perris Valley Line, an extension of Metrolink 91 Line service to stations at Hunter Park, March Air Reserve Base, Perris, and South Perris.

At the southern end the section between San Diego and Oceanside also sees heavy use by Amtrak California's Pacific Surfliner trains as well as those of the San Diego Coaster. As part of the Santa Fe's rail network, it was part of what has come to be known as the Surf Line. As of January 2006, this line is the second busiest passenger rail line in the United States.[35]

Although San Diego's Union Station replaced the railroad's original station there in 1915, the California Southern's station and office building in National City has been preserved and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[36]

References

- Notes

- ↑ Serpico, p 18

- ↑ Waters, p 72, and Serpico, p 18.

- ↑ Waters, p 64-65.

- ↑ Waters, p 65.

- ↑ Waters, pp 69-71.

- 1 2 Waters, p 73.

- ↑ Dodge, Richard V. (April 10, 1958). "The Fallbrook Line". Retrieved July 9, 2006.

- ↑ Serpico, p 18-19.

- ↑ Huffman, Wendell W. (Spring 1999). "Railroads Shipped by Sea". Railroad History (180): 7–30. Retrieved July 9, 2006.

- ↑ Duke and Kistler, p 22.

- 1 2 Duke and Kistler, p 27

- ↑ "A Chinese American in 1884; Floods, Fall Brook And Fallbrook". Fallbrook Historical Society. 1998. Archived from the original on February 19, 2007. Retrieved March 7, 2007.

- ↑ Duke and Kistler, p 29.

- ↑ Duke and Kistler, p 43

- 1 2 Serpico, Philip C. (1988). Santa Fé Route to the Pacific. Palmdale, California: Omni Publications. ISBN 0-88418-000-X.

- ↑ Waters, Leslie L. (1950). Steel Trails to Santa Fe. Lawrence, Kansas: University of Kansas Press.

- ↑ The Earp Brothers of Tombstone: The Memoirs of Alvira Earp, by Frank Waters

- ↑ Serpico, p 20.

- ↑ Walker, Chard (1990). Cajon: A Pictorial Album. Glendale, California: Trans-Anglo Books. p. 10. ISBN 0-87046-095-1.

- ↑ Waters, p 74.

- 1 2 Duke and Kistler, p 32

- ↑ Signor, p 18.

- ↑ Signor, p 37.

- ↑ Yenne, Bill (1985). The History of the Southern Pacific. Bonanza, New York, NY. p. 122. ISBN 0-517-46084-X.

- ↑ City of Victorville, California (22 August 2014). "City History". Retrieved August 22, 2014.

- ↑ Serpico, p 23-24.

- ↑ Serpico, p 26.

- ↑ Serpico, p 30.

- ↑ Serpico, p 34

- ↑ Duke and Kistler, p 45-46.

- ↑ Poor's Directory of Railway Officials. New York and London: Poor's Railroad Manual Company. 1887. p. 23.

- ↑ The Official Railway List. Chicago: Railway Purchasing Agent Company. 1888. p. 25.

- ↑ San Bernardino Associated Governments (2004). "A Brief History of the Santa Fe Depot". Archived from the original on September 23, 2006. Retrieved July 17, 2006.

- ↑ San Bernardino Convention and Visitors Bureau (2006). "A Brief History of San Bernardino". Retrieved July 17, 2006.

- ↑ Amtrak (January 2006). "Monthly Performance Report for January 2006" (PDF). Retrieved July 10, 2006.

- ↑ "National Register of Historic Places: California - San Diego County - Vacant / Not In Use". Retrieved July 9, 2006.

- Sources

- Duke, Donald; Kistler, Stan (1963). Santa Fe ...Steel Rails Through California. San Marino, California: Golden West Books. ISBN 0-87095-009-6.

- The Official Railway List. Chicago: Railway Purchasing Agent Company. 1888.

- Serpico, Philip C. (1988). Santa Fé Route to the Pacific. Palmdale, California: Omni Publications. ISBN 0-88418-000-X.

- Signor, John R. (1988). The Los Angeles and Salt Lake Railroad Company; Union Pacific's Historic Salt Lake Route. San Marino, California: Golden West Books. ISBN 0-87095-101-7.

- Waters, Leslie L. (1950). Steel Trails to Santa Fe. Lawrence, Kansas: University of Kansas Press.

Further reading

- Duke, Donald (1995). Santa Fe...The Railroad Gateway to the American West. 1. San Marino, CA: Golden West Books. ISBN 0-8709-5110-6. OCLC 32745686.

- Eichstadt, Howard (October 1941). "Cajon Pass". Trains: 38.

- Hoyt, Franklyn. San Diego's first railroad: The California Southern. ASIN B0007FWTA2.

- Middlebrook, R.P. (November 1957). "Santa Fe Fallbrook Branch". Pacific Railway Journal. San Marino, California: Southern California Chapter, Railway and Locomotive Historical Society. 2 (4).

- Walker, Chard (1987). Cajon: Rail Passage to the Pacific. Interurban Press. ISBN 0-87046-072-2.

External links

- The California Southern Railroad and the Growth of San Diego - Part I and Part II; from the Journal of San Diego History.

- A Chinese American in 1884: Floods, Fall Brook And Fallbrook; describes the washouts in Temecula Canyon in 1884. (Dead link)

- Perris and its Railroad; by Richard V. Dodge, 1959.

- Santa Fe Railroad Routes in Southern California 1888