Cape Verde hurricane

A Cape Verde hurricane is an Atlantic hurricane that originates at low-latitude in the deep tropics, titularly from a tropical wave that has passed over or near the Cape Verde islands after exiting the coast of West Africa. The average hurricane season has about two Cape Verde hurricanes, which are often the largest and most intense storms of the season due to having plenty of warm open ocean over which to develop before encountering land or other factors prompting weakening. A good portion of Cape Verde storms are large, some setting records. Most of the longest-lived tropical cyclones in the Atlantic basin are Cape Verde hurricanes. While many move harmlessly out to sea, some move across the Caribbean sea and into the Gulf of Mexico, becoming damaging storms for Caribbean nations, Central America, Mexico, Bermuda, the United States, and occasionally even Canada. Research projects since the 1970s have been launched to understand the formation of these storms.

Origin

Prior to the early 1940s, the term Cape Verde hurricane referred to August and early September storms that formed to the east of the surface plotting charts in use at the time.[1] Cape Verde hurricanes typically develop from tropical waves which form in the African savanna during the wet season, then move into the African steppes. The disturbances move off the western coast of Africa and become tropical storms or tropical cyclones soon after moving off the coast,[2] within 10 to 15 degrees longitude, or 10,760 kilometres (6,690 mi) to 16,140 kilometres (10,030 mi), of the Cape Verde Islands;[1] this comprises the tropical latitudes east of the 40th meridian west. In the years since the phrase's coining, increasing detection has allowed meteorologists to determine that Cape Verde hurricanes have formed as early as July 4 (Hurricane Bertha of 1996) or as late as September 26 (Hurricane Flora).

Typical tracks

A Cape Verde hurricane forms from a tropical depression or tropical wave which passed through or near the Cape Verde islands, and strengthens into a named system (eventually becoming a hurricane at some point) in the mid-Atlantic. The initial track of a Cape Verde storm tends to be generally westward from Cape Verde, with a turn to the north at some stage in the track for most storms lasting more than a few days. Once the cyclone begins approaching South America, a Cape Verde hurricane can take several basic tracks and from there diverge, become extra-tropical, or dissipate.

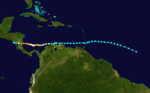

- It can continue to the west, and if it is far enough south, it will cross the Windward Islands into the Caribbean Sea, possibly affecting Venezuela to some degree. From there it will often continue westward into Nicaragua, Honduras, or Belize.[3] For example, Hurricane Joan–Miriam took this southerly route in 1988, causing severe flooding in South America, making landfall in Central America, and continuing into the Pacific Basin, just as Hurricane Irene–Olivia did in 1971. Rarely, a storm will make landfall in South America.

Joan (1988), on a southern track.

Joan (1988), on a southern track. - Some storms pass unabated into the Gulf of Mexico. Hurricane Ivan of 2004 began with a very southerly route yet it made landfall far to the north in Alabama. Somewhere in the middle of these extremes, storms such as 1980's Hurricane Allen track toward the coast of Mexico, affecting areas from the Yucatán Peninsula to Texas. Many of these southerly hurricanes strike Jamaica, like the Galveston Hurricane of 1915 and Hurricane Gilbert of 1988. Hurricane Janet of 1955 will be remembered as one of the deadliest and strongest storms to strike the Yucatán Peninsula of Mexico.

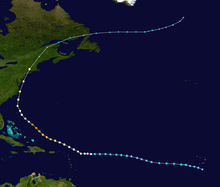

Emily (2005), on a Mexican track.

Emily (2005), on a Mexican track. - If the storm is further north, it may travel past the Leeward Islands and into the Greater Antilles. In 1998, Hurricane Georges took a track of this nature as it continued into Mississippi. Slightly further north, and the storm will track through the Bahamas and into Florida in the manner of 1992's Hurricane Andrew.[3] Many of these storms passing through the center of the Caribbean will strike the islands of Hispaniola and Cuba, like Hurricane David and Hurricane Frederic did, both in 1979. Some storms on this track will turn to the west once in the Gulf, and thereby make landfall in Texas, as the Galveston Hurricane of 1900 and Hurricane Ike of 2008 did. Similarly, Hurricane Inez of 1966 followed a Caribbean track that took the storm into the Bahamas where it weakened, only to turn sharply west and make a final landfall in Mexico.

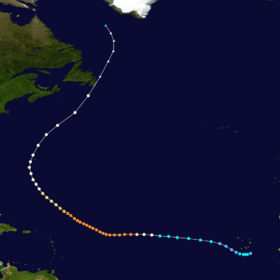

Georges (1998), on a Caribbean track.

Georges (1998), on a Caribbean track. - A more northerly storm will often have its track affected by the high pressure that typically occurs over the eastern Atlantic in late summer. As these storms pass north of the Antilles, their tracks begin to curve to the north and to the east of the Florida Peninsula, often sending them away from land. A few storms will track northwest, making landfall in North or South Carolina. Hurricane Hugo of 1989 and Hurricane Fran of 1996 are typical examples. Occasionally storms following this track can accelerate to the north and strike New England. The New England Hurricane of 1938 and Hurricane Gloria in 1985 were two such cases.[3]

Gloria (1985) struck the East Coast.

Gloria (1985) struck the East Coast. - When a storm tracks very far north, its potential for landfall is much less. Some of these storms will strike Bermuda before re-curving out to sea, such as the 1948 Bermuda–Newfoundland hurricane and Hurricane Fabian in 2003. Occasionally, the storm will track west-northwest to strike the Atlantic coast of the U.S., such as the 1933 Chesapeake–Potomac hurricane and Hurricane Isabel of 2003, which struck the mid-Atlantic. Other Cape Verde storms make landfall in Canada, such as Hurricane Luis in 1995 and Hurricanes Earl and Igor of 2010. If the storm's track is affected significantly, it will often pass near the Eastern U.S., Nova Scotia, and Newfoundland Island and curve back out to sea, where it becomes extratropical over cooler water. An example of such was Hurricane Edouard in 1996. At the extreme, Cape Verde hurricanes can track so far north as to curve all the way to Europe, such as Hurricane Debbie of 1961, Hurricane Isaac of 2000, and Hurricane Katia of 2011, all of which affected Ireland.

Igor (2010) struck Atlantic Canada.

Igor (2010) struck Atlantic Canada. - Sometimes, the subtropical ridge is displaced from its normal position, which allows storms to recurve quickly by being driven around the east side of an upper trough in the central Atlantic, generally missing land completely as they dissipate. Both Hurricane Danielle and Hurricane Karl were affected like this in 2004.[3] In other cases, storms are steered north very early in their development near Cape Verde, such as the 1989 storms Hurricane Erin and Hurricane Felix, which both traveled northwest and never threatened land. However, in extremely rare cases, these storms will hit Cape Verde or the Azores at a significant intensity. Some notable examples of this include Hurricane Fred, which hit Cape Verde in 2015, and a hurricane which struck the Azores in 1893; both of which wrought considerable destruction.

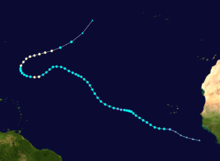

Philippe (2011) dissipated in the central Atlantic.

Philippe (2011) dissipated in the central Atlantic.

Because most Cape Verde hurricanes take a near-westward path that starts in the eastern Atlantic, they can avoid the two situations that typically end the life of a tropical cyclone: interaction with land, and movement over cool water. Since storms that far out at sea can go over a week without moving over cooler water or near a landmass, Cape Verde hurricanes are some of the longest-lived storms. Hurricane Faith, the third longest lasting Atlantic hurricane on record,[3] was a Cape Verde hurricane. It lasted 16 days total and was a hurricane for 14.[4] Hurricane Joan–Miriam of 1988 and Hurricane Irene–Olivia of 1971 lasted longer, both having crossed narrow parts of Central America and regaining cyclonic motion in the Pacific.

Research

Twenty nations took part in the GATE research project in 1974, where Douglas DC-6 aircraft examined tropical waves which spawn Cape Verde hurricanes.[5] In 2006, there was a two-month research project known as NAMMA-06 (short for NASA African Monsoon Multidisciplinary Activities)[6] which flew Douglas DC-8s into seedling disturbances in the eastern Atlantic which had the potential to become Cape Verde hurricanes.[7][8]

See also

References

- 1 2 Gordon E. Dunn; Banner I. Miller (1960). Atlantic Hurricanes. Louisiana State University Press. p. 54. ASIN B0006BM85S.

- ↑ Chris Landsea (1997-07-18). "FAQ: HURRICANES, TYPHOONS AND TROPICAL CYCLONES (Part 1 of 2) Subject: A2) What are "Cape Verde"-type hurricanes?". Faqs.org. Retrieved 2009-10-08.

- 1 2 3 4 5 National Hurricane Center; Hurricane Research Division (July 6, 2016). "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)". United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved December 5, 2016.

- ↑ Colin J. McAdie; Christopher W. Landsea; Charles J. Neumann; Joan E. David; Eric S. Blake; Gregory R. Hammer (2009). Historical Climatology Series 6-2: Tropical Cyclones of the North Atlantic Ocean, 1851–2006 (with 2007 and 2008 track maps included) (PDF). National Climatic Data Center. p. 161. Retrieved 2009-10-08.

- ↑ National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (2007-02-01). "Feature Stories : Fifty Years of NOAA Hurricane Research". Department of Commerce. Retrieved 2010-01-20.

- ↑ R. K. Kakar (Fall 2006). "NASA's Three Pronged Approach to Hurricane Research". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2010-01-20.

- ↑ Jon Hamilton (2006-10-17). "Off Africa's Coast, a Hurricane Nursery". National Public Radio. Retrieved 2010-01-20.

- ↑ Marc Kaufman (2006-08-07). "Research Team Seeking Clues to a Hurricane's Birth". Washington Post. Retrieved 2010-01-20.

External links

- NOAA AOML Hurricane Research Division definition of a Cape Verde hurricane

- Talks about hurricanes in general and Cape Verde hurricanes