Chach Nama

Chach Nama (Sindhi: چچ نامو; Urdu: چچ نامہ), also known as the Fateh nama Sindh (Sindhi: فتح نامه سنڌ), and as Tarekh-e-Hind wa Sindh Arabic (تاريخ الهند والسند), one of the main historical sources for the history of Sindh in the seventh to eighth centuries CE. It is in Persian.

Contents

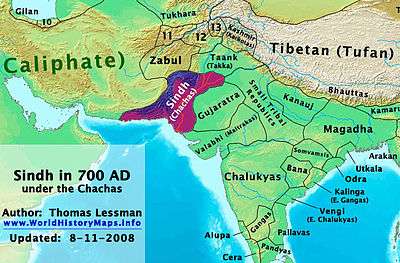

It contains an introductory chapter about the history of Sindh just before its conquest by the Arabs. The body of the work narrates the Arab inclursions into Sindh of the 7th-8th centuries CE.[1] Thus it chronicls the Chacha Dynasty's period, following the demise of the Rai Dynasty and the ascent of Chach of Alor to the throne, down to the Arab conquest by Muhammad bin Qasim in early 8th century CE.[2] The text concludes with 'an epilogue describing the tragic end of the Arab commander Muḥammad b. al-Ḳāsim and of the two daughters of Dāhir, the defeated king of Sind'.[3]

Historical Significance

As one of the only written sources about the Arab conquest of Sindh, and therefore the origins of Islam in India, the Chach Nama is a key historical text that has been co-opted by different interest groups for several centuries, and it has significant implications for modern imaginings about the place of Islam in South Asia. Accordingly, its implications are much disputed.[4] According to Modern South Asia by historians Sugata Bose and Ayesha Jalal:

| “ | The Chachnama, the principal source of our information on the Muslim conquest of Sind, elaborates a royal code which demands sensitivity to the fluidity and shifting nature of the real world of politics. This is in contrast to Kautilya’s ‘classical’ and largely theoretical text Arthashastra, which advises princes on ways to avoid the dilution of absolute and centralized power. The pardoning of a fallen enemy, described by the Chachnama, provided a quick route to legitimacy by renegotiating a balance between different hierarchically arranged layers of sovereignty. The Arab conquest of Sind, instead of representing a sharp disjuncture, can be seen as a form of adaptation to pre-existing political conditions in India. | ” |

Origins, authorship, and preservation

As we have it today, the Chach Nama is the work of ʿAlī b. Ḥāmid b. Abī Bakr Kūfī. He was writing in Persian, but claimed to be translating a book in Arabic, which he had discovered among the possessions of the ḳāḍī of Alōr, Ismāʿīl b. ʿAlī ... b. ʿUthmān al-Thaḳafī (who was appointed the first kādī of Alōr by Muhammad Kāsim after the conquest of the Sindh.[5])[6] It is possible, however, that no such book existed and that the work is entirely a composition by ʿAlī (a view championed in 2016 by Manan Ahmed Asif),[7] leading to debate about the source-value of the Chach Nama. In the assessment of Y. Friedmann,

a comparison between the Čač-Nāma and Arab historians such as Balādhurī [...] bears out the Arab provenance of those parts of the book that describe the battles leading to the conquest of Sind; Kūfī might well have used Madāʾinī’s Kitāb Thaghr al-Hind and Kitāb ʿUmmāl (or Aʿmāl) al-Hind [...] The Čač-Nāma seems to have preserved Madāʾinī’s tradition concerning India in a much fuller fashion than classical Arab histories. On the other hand, the book also comprises a considerable amount of material which probably reflects a local Indian historical tradition. The part dealing with the rise of the Čač dynasty (14-72), the story of Darōhar, Djaysinha and Djanki (229-234), and some traditions attributed to a Brahman called Rāmsiya (179) and to “some Brahman elders” (baʿḍī mashāyikh-i barāhima) (197; cf. also 20614) deserve to be mentioned in this context.[8]

At one time it was considered to be a romance until Mountstuart Elphinstone's observations of its partial historical veracity.

The Chach Nama survived in the folllowing key manuscripts: British Library Or. 1787; India Office, Ethé 435.[9]

Accuracy

The Táríkh Maasúmí, and the Tuhfatulkirám are two other Muslim histories of the same period and on occasion give differing accounts of some details. Later Muslim chronicles like those by Nizamuddin Ahmad, Nurul Hakk, Firishta, and Masum Shah draw their account of the Arab conquest from the Chach Nama.

While Muhammad Ali bin Hamid bin Abu Bakr Kufi is also seen as having employed some "Purple prose", he is regarded as having accurately translated the bulk of the Arabic material as well attributing the sources of information, whether they are from individuals or even "tradition".

As a historical narrative, the account is seen as a valuable record of events such as the social, political and historical geography of the region at the time, while containing the natural bias of the Sakifi family as well as the inherent inaccuracies and embellishments of popular tradition.

Further reading

- Siddiqi, Iqtidar Husain (2010), Indo-Persian Historiography Up to the Thirteenth Century, Primus Books, pp. 30–, ISBN 978-81-908918-0-6

- Y. Friedmann, The origins and significance of the Chach Nāma, in Y. Friedmann (ed.), Islam in Asia. 1. South Asia, Jerusalem 1984, 23-37.

- Manan Ahmed Asif, A Book of Conquest: The Chachnama and Muslim Origins in South Asia (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016)

Editions and Translations

- Elliot, H. M. and Dowson, John. (1867). Chach-Nama. In The History of India: As Told by its Own Historians - The Muhammadan Period, Volume 1, pp. 131-211. London: Trubner. (Description and partial translation.)

- The Chachnamah, An Ancient History of Sind, Giving the Hindu period down to the Arab Conquest. (1900). Translated from the Persian by Mirza Kalichbeg Fredunbeg. Karachi: Commissioners Press. (Online at: Persian Packhum)

- Makhdūm Amīr Aḥmad and Nabī Bakhsh Ḵhān Balōč, Fatḥ-Nāmayi Sind, Ḥaydarābād (Sind) 1966. (Sindī translation and commentary.)

- Nabi Bakhsh Khan Baloch, Chachnama (Islamabad, 1983). (Annotated critical edition.)

References

- ↑ Y. Friedmann, “Čač-Nāma”, in Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, ed. by P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, and W.P. Heinrichs (Leiden: Brill, 1960-2007). Consulted online on 04 December 2016 DOI:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_8436.

- ↑ The Chachnamah, An Ancient History of Sind, Giving the Hindu period down to the Arab Conquest. (1900). Translated from the Persian by Mirza Kalichbeg Fredunbeg. Karachi: Commissioners Press.

- ↑ Y. Friedmann, “Muḥammad b. al- Ḳāsim”, in Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, ed. by P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, and W.P. Heinrichs (Leiden: Brill, 1960-2007). Consulted online on 04 December 2016 DOI:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_8436.

- ↑ E.g. Syed Nomanul Haq, 'Gujarati Sandals in Baghdad: Decolonising History' [review of Manan Ahmed Asif, A Book of Conquest: The Chachnama and Muslim Origins in South Asia (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016)], Herald (19 November 2016), http://herald.dawn.com/news/1153594/gujarati-sandals-in-baghdad-decolonising-history.

- ↑ History of Sind. Vol. II. (In two parts) Part II—Giving the Reigns of the Kalhórahs and the Tálpurs down to the British Conquest. Translated from Persian by Mirza Kalichbeg Fredunbeg, Chapter IV.

- ↑ Y. Friedmann, “Čač-Nāma”, in Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, ed. by P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, and W.P. Heinrichs (Leiden: Brill, 1960-2007). Consulted online on 04 December 2016 DOI:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_8436.

- ↑ Manan Ahmed Asif, A Book of Conquest: The Chachnama and Muslim Origins in South Asia (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016).

- ↑ Y. Friedmann, “Čač-Nāma”, in Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, ed. by P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, and W.P. Heinrichs (Leiden: Brill, 1960-2007). Consulted online on 04 December 2016 DOI:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_8436.

- ↑ Y. Friedmann, “Čač-Nāma”, in Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, ed. by P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, and W.P. Heinrichs (Leiden: Brill, 1960-2007). Consulted online on 04 December 2016 DOI:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_8436.