Charles Baudelaire

| Charles Baudelaire | |

|---|---|

Charles Baudelaire by Étienne Carjat, 1863 | |

| Born |

Charles Pierre Baudelaire April 9, 1821 Paris, France |

| Died |

August 31, 1867 (aged 46) Paris, France |

| Occupation | Poet, art critic |

| Nationality | French |

| Period | 1844–1866 |

| Literary movement | Symbolist, Modernist |

|

| |

| Signature |

|

| French literature |

|---|

| by category |

| French literary history |

| French writers |

|

| Portals |

|

Charles Pierre Baudelaire (/ˌboʊdəlˈɛər/;[1] French: [ʃaʁl bodlɛʁ]; April 9, 1821 – August 31, 1867) was a French poet who also produced notable work as an essayist, art critic, and pioneering translator of Edgar Allan Poe.

His most famous work, Les Fleurs du mal (The Flowers of Evil), expresses the changing nature of beauty in modern, industrializing Paris during the 19th century. Baudelaire's highly original style of prose-poetry influenced a whole generation of poets including Paul Verlaine, Arthur Rimbaud and Stéphane Mallarmé among many others. He is credited with coining the term "modernity" (modernité) to designate the fleeting, ephemeral experience of life in an urban metropolis, and the responsibility art has to capture that experience.[2]

Baudelaire the poet

Who among us has not dreamt, in moments of ambition, of the miracle of a poetic prose, musical without rhythm and rhyme, supple and staccato enough to adapt to the lyrical stirrings of the soul, the undulations of dreams, and sudden leaps of consciousness. This obsessive idea is above all a child of giant cities, of the intersecting of their myriad relations.— Dedication of Le Spleen de Paris

Baudelaire is one of the major innovators in French literature. His poetry is influenced by the French romantic poets of the earlier 19th century, although its attention to the formal features of verse connects it more closely to the work of the contemporary "Parnassians". As for theme and tone, in his works we see the rejection of the belief in the supremacy of nature and the fundamental goodness of man as typically espoused by the romantics and expressed by them in rhetorical, effusive and public voice in favor of a new urban sensibility, an awareness of individual moral complexity, an interest in vice (linked with decadence) and refined sensual and aesthetic pleasures, and the use of urban subject matter, such as the city, the crowd, individual passers-by, all expressed in highly ordered verse, sometimes through a cynical and ironic voice. Formally, the use of sound to create atmosphere, and of "symbols" (images that take on an expanded function within the poem), betray a move towards considering the poem as a self-referential object, an idea further developed by the Symbolists Verlaine and Mallarmé, who acknowledge Baudelaire as a pioneer in this regard.

Beyond his innovations in versification and the theories of symbolism and "correspondences", an awareness of which is essential to any appreciation of the literary value of his work, aspects of his work that regularly receive much critical discussion include the role of women, the theological direction of his work and his alleged advocacy of "satanism", his experience of drug-induced states of mind, the figure of the dandy, his stance regarding democracy and its implications for the individual, his response to the spiritual uncertainties of the time, his criticisms of the bourgeois, and his advocacy of modern music and painting (e.g., Wagner, Delacroix). He made Paris the subject of modern poetry. He would bring the city's details to life in the eyes and hearts of his readers.[3]

Early life

Baudelaire was born in Paris, France, on April 9, 1821, and baptized two months later at Saint-Sulpice Roman Catholic Church.[4] His father, François Baudelaire, a senior civil servant and amateur artist, was 34 years older than Baudelaire's mother, Caroline. François died during Baudelaire's childhood, in 1827. The following year, Caroline married Lieutenant Colonel Jacques Aupick, who later became a French ambassador to various noble courts. Baudelaire's biographers have often seen this as a crucial moment, considering that finding himself no longer the sole focus of his mother's affection left him with a trauma, which goes some way to explaining the excesses later apparent in his life. He stated in a letter to her that, "There was in my childhood a period of passionate love for you."[5] Baudelaire regularly begged his mother for money throughout his career, often promising that a lucrative publishing contract or journalistic commission was just around the corner.

Baudelaire was educated in Lyon, where he boarded. At fourteen he was described by a classmate as "much more refined and distinguished than any of our fellow pupils [...] we are bound to one another [...] by shared tastes and sympathies, the precocious love of fine works of literature."[6] Baudelaire was erratic in his studies, at times diligent, at other times prone to "idleness". Later, he attended the Lycée Louis-le-Grand in Paris, studying law, a popular course for those not yet decided on any particular career. He began to frequent prostitutes and may have contracted gonorrhea and syphilis during this period. He also began to run up debts, mostly for clothes. Upon gaining his degree in 1839, he told his brother "I don't feel I have a vocation for anything." His stepfather had in mind a career in law or diplomacy, but instead Baudelaire decided to embark upon a literary career. His mother later recalled: "Oh, what grief! If Charles had let himself be guided by his stepfather, his career would have been very different.... He would not have left a name in literature, it is true, but we should have been happier, all three of us."[7]

His stepfather sent him on a voyage to Calcutta, India, in 1841 in the hope of ending his dissolute habits. The trip provided strong impressions of the sea, sailing, and exotic ports, that he later employed in his poetry.[8] (Baudelaire later exaggerated his aborted trip to create a legend about his youthful travels and experiences, including "riding on elephants".) On returning to the taverns of Paris, he began to compose some of the poems of "Les Fleurs du Mal". At 21, he received a sizable inheritance but squandered much of it within a few years. His family obtained a decree to place his property in trust,[9] which he resented bitterly, at one point arguing that allowing him to fail financially would have been the one sure way of teaching him to keep his finances in order.

Baudelaire became known in artistic circles as a dandy and free-spender. During this time, Jeanne Duval became his mistress. She was rejected by his family. His mother thought Duval a "Black Venus" who "tortured him in every way" and drained him of money at every opportunity.[10] Baudelaire made a suicide attempt during this period.

He took part in the Revolutions of 1848 and wrote for a revolutionary newspaper. However, his interest in politics was passing, as he was later to note in his journals.

In the early 1850s, Baudelaire struggled with poor health, pressing debts, and irregular literary output. He often moved from one lodging to another to escape creditors. He undertook many projects that he was unable to complete, though he did finish translations of stories by Edgar Allan Poe.

Upon the death of his stepfather in 1857, Baudelaire received no mention in the will but he was heartened nonetheless that the division with his mother might now be mended. At 36 he wrote her: "believe that I belong to you absolutely, and that I belong only to you".[11]

Published career

His first published work was his art review "Salon of 1845", which attracted immediate attention for its boldness. Many of his critical opinions were novel in their time, including his championing of Delacroix, and some of his views seem remarkably in tune with the future theories of the Impressionist painters.

In 1846, Baudelaire wrote his second Salon review, gaining additional credibility as an advocate and critic of Romanticism. His support of Delacroix as the foremost Romantic artist gained widespread notice.[12] The following year Baudelaire's novella La Fanfarlo was published.

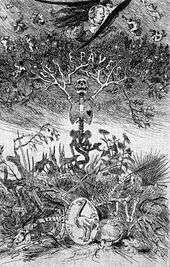

The Flowers of Evil

Baudelaire was a slow and fastidious worker, often sidetracked by indolence, emotional distress and illness, and it was not until 1857 that he published his first and most famous volume of poems, Les Fleurs du mal (The Flowers of Evil).[13] Some of these poems had already appeared in the Revue des deux mondes (Review of Two Worlds) in 1855, when they were published by Baudelaire's friend Auguste Poulet Malassis.[14][15] Some of the poems had also previously appeared as "fugitive verse" in various French magazines during the previous decade.[16]

The poems found a small, appreciative audience, but greater public attention was given to their subject matter. The effect on fellow artists was, as Théodore de Banville stated, "immense, prodigious, unexpected, mingled with admiration and with some indefinable anxious fear".[17] Gustave Flaubert, recently attacked in a similar fashion for Madame Bovary (and acquitted), was impressed and wrote to Baudelaire: "You have found a way to rejuvenate Romanticism.... You are as unyielding as marble, and as penetrating as an English mist."[18]

The principal themes of sex and death were considered scandalous. He also touched on lesbianism, sacred and profane love, metamorphosis, melancholy, the corruption of the city, lost innocence, the oppressiveness of living, and wine. Notable in some poems is Baudelaire's use of imagery of the sense of smell and of fragrances, which is used to evoke feelings of nostalgia and past intimacy.[19]

The book, however, quickly became a byword for unwholesomeness among mainstream critics of the day. Some critics called a few of the poems "masterpieces of passion, art and poetry" but other poems were deemed to merit no less than legal action to suppress them.[20] J. Habas writing in Le Figaro, led the charge against Baudelaire, writing: "Everything in it which is not hideous is incomprehensible, everything one understands is putrid." Then Baudelaire responded to the outcry, in a prophetic letter to his mother:

"You know that I have always considered that literature and the arts pursue an aim independent of morality. Beauty of conception and style is enough for me. But this book, whose title (Fleurs du mal) says everything, is clad, as you will see, in a cold and sinister beauty. It was created with rage and patience. Besides, the proof of its positive worth is in all the ill that they speak of it. The book enrages people. Moreover, since I was terrified myself of the horror that I should inspire, I cut out a third from the proofs. They deny me everything, the spirit of invention and even the knowledge of the French language. I don't care a rap about all these imbeciles, and I know that this book, with its virtues and its faults, will make its way in the memory of the lettered public, beside the best poems of V. Hugo, Th. Gautier and even Byron."[21]

Baudelaire, his publisher and the printer were successfully prosecuted for creating an offense against public morals. They were fined, but Baudelaire was not imprisoned.[22] Six of the poems were suppressed, but printed later as Les Épaves (The Wrecks) (Brussels, 1866). Another edition of Les Fleurs du mal, without these poems, but with considerable additions, appeared in 1861. Many notables rallied behind Baudelaire and condemned the sentence. Victor Hugo wrote to him: "Your fleurs du mal shine and dazzle like stars.... I applaud your vigorous spirit with all my might."[23] Baudelaire did not appeal the judgment, but his fine was reduced. Nearly 100 years later, on May 11, 1949, Baudelaire was vindicated, the judgment officially reversed, and the six banned poems reinstated in France.[23]

In the poem "Au lecteur" ("To the Reader") that prefaces Les Fleurs du mal, Baudelaire accuses his readers of hypocrisy and of being as guilty of sins and lies as the poet:

- ... If rape or arson, poison or the knife

- Has wove no pleasing patterns in the stuff

- Of this drab canvas we accept as life—

- It is because we are not bold enough!

- (Roy Campbell's translation)

Final years

Baudelaire next worked on a translation and adaptation of Thomas De Quincey's Confessions of an English Opium Eater.[24] Other works in the years that followed included Petits Poèmes en prose (Small Prose poems); a series of art reviews published in the Pays, Exposition universelle (Country, World Fair); studies on Gustave Flaubert (in L'Artiste, October 18, 1857); on Théophile Gautier (Revue contemporaine, September 1858); various articles contributed to Eugene Crepet's Poètes francais; Les Paradis artificiels: opium et haschisch (French poets; Artificial Paradises: opium and hashish) (1860); and Un Dernier Chapitre de l'histoire des oeuvres de Balzac (A Final Chapter of the history of works of Balzac) (1880), originally an article "Comment on paye ses dettes quand on a du génie" ("How one pays one's debts when one has genius"), in which his criticism turns against his friends Honoré de Balzac, Théophile Gautier, and Gérard de Nerval.[14]

By 1859, his illnesses, his long-term use of laudanum, his life of stress and poverty had taken a toll and Baudelaire had aged noticeably. But at last, his mother relented and agreed to let him live with her for a while at Honfleur. Baudelaire was productive and at peace in the seaside town, his poem Le Voyage being one example of his efforts during that time.[25] In 1860, he became an ardent supporter of Richard Wagner.

His financial difficulties increased again, however, particularly after his publisher Poulet Malassis went bankrupt in 1861. In 1864, he left Paris for Belgium, partly in the hope of selling the rights to his works and also to give lectures.[26] His long-standing relationship with Jeanne Duval continued on-and-off, and he helped her to the end of his life. Baudelaire's relationships with actress Marie Daubrun and with courtesan Apollonie Sabatier, though the source of much inspiration, never produced any lasting satisfaction. He smoked opium, and in Brussels he began to drink to excess. Baudelaire suffered a massive stroke in 1866 and paralysis followed. After more than a year of aphasia, he received the last rites of the Catholic Church.[27] The last two years of his life were spent, in a semi-paralyzed state, in "maisons de santé" in Brussels and in Paris, where he died on August 31, 1867. Baudelaire is buried in the Cimetière du Montparnasse, Paris.

Many of Baudelaire's works were published posthumously. After his death, his mother paid off his substantial debts, and at last she found some comfort in Baudelaire's emerging fame. "I see that my son, for all his faults, has his place in literature." She lived another four years.

Critiques

Baudelaire was an active participant in the artistic life of his times. As critic and essayist, he wrote extensively and perceptively about the luminaries and themes of French culture. He was frank with friends and enemies, rarely took the diplomatic approach and sometimes responded violently verbally, which often undermined his cause.[28] His associations were numerous and included: Gustave Courbet, Honoré Daumier, Franz Liszt, Champfleury, Victor Hugo, Gustave Flaubert, Balzac and the artists and writers that follow.

Edgar Allan Poe

In 1847, Baudelaire became acquainted with the works of Poe, in which he found tales and poems that had, he claimed, long existed in his own brain but never taken shape. Baudelaire had much in common with Poe (who died in 1849 at age forty). The two poets display a similar sensibility of the macabre and supernatural turn of mind; each struggled with illness, poverty, and melancholy. Like Poe, Baudelaire believed in the doctrine of original sin, denounced democracy and the idea of progress and of man's natural goodness, and Poe held a disdainful aristocratic attitude similar to Baudelaire's dandy.[29] Baudelaire saw in Poe a precursor and tried to be his French contemporary counterpart.[30] From this time until 1865, he was largely occupied with translating Poe's works; his translations were widely praised. Baudelaire was not the first French translator of Poe, but his "scrupulous translations" were considered among the best. These were published as Histoires extraordinaires (Extraordinary stories) (1852), Nouvelles histoires extraordinaires (New extraordinary stories) (1857), Aventures d'Arthur Gordon Pym, Eureka, and Histoires grotesques et sérieuses (Grotesque and serious stories) (1865). Two essays on Poe are to be found in his Oeuvres complètes (Complete works) (vols. v. and vi.).

Eugène Delacroix

A strong supporter of the Romantic painter Delacroix, Baudelaire called him "a poet in painting". Baudelaire also absorbed much of Delacroix's aesthetic ideas as expressed in his journals. As Baudelaire elaborated in his "Salon of 1846", "As one contemplates his series of pictures, one seems to be attending the celebration of some grievous mystery.... This grave and lofty melancholy shines with a dull light ... plaintive and profound like a melody by Weber."[12] Delacroix, though appreciative, kept his distance from Baudelaire, particularly after the scandal of Les Fleurs du mal. In private correspondence, Delacroix stated that Baudelaire "really gets on my nerves" and he expressed his unhappiness with Baudelaire's persistent comments about "melancholy" and "feverishness".[31]

Richard Wagner

Baudelaire had no formal musical training, and knew little of composers beyond Beethoven and Weber. Weber was in some ways Wagner's precursor, using the leitmotif and conceiving the idea of the "total art work" ("Gesamtkunstwerk"), both of which gained Baudelaire's admiration. Before even hearing Wagner's music, Baudelaire studied reviews and essays about him, and formulated his impressions. Later, Baudelaire put them into his non-technical analysis of Wagner, which was highly regarded, particularly his essay "Richard Wagner et Tannhäuser à Paris".[32] Baudelaire's reaction to music was passionate and psychological. "Music engulfs (possesses) me like the sea."[32] After attending three Wagner concerts in Paris in 1860, Baudelaire wrote to the composer: "I had a feeling of pride and joy in understanding, in being possessed, in being overwhelmed, a truly sensual pleasure like that of rising in the air."[33] Baudelaire's writings contributed to the elevation of Wagner and to the cult of Wagnerism that swept Europe in the following decades.

Théophile Gautier

Gautier, writer and poet, earned Baudelaire's respect for his perfection of form and his mastery of language, though Baudelaire thought he lacked deeper emotion and spirituality. Both strove to express the artist's inner vision, which Heinrich Heine had earlier stated: "In artistic matters, I am a supernaturalist. I believe that the artist can not find all his forms in nature, but that the most remarkable are revealed to him in his soul."[34] Gautier's frequent meditations on death and the horror of life are themes which influenced Baudelaire's writings. In gratitude for their friendship and commonality of vision, Baudelaire dedicated Les Fleurs du mal to Gautier.

Édouard Manet

Manet and Baudelaire became constant companions from around 1855. In the early 1860s, Baudelaire accompanied Manet on daily sketching trips and often met him socially. Manet also lent Baudelaire money and looked after his affairs, particularly when Baudelaire went to Belgium. Baudelaire encouraged Manet to strike out on his own path and not succumb to criticism. "Manet has great talent, a talent which will stand the test of time. But he has a weak character. He seems to me crushed and stunned by shock."[35] In his painting Music in the Tuileries, Manet includes portraits of his friends Théophile Gautier, Jacques Offenbach, and Baudelaire.[36] While it's difficult to differentiate who influenced whom, both Manet and Baudelaire discussed and expressed some common themes through their respective arts. Baudelaire praised the modernity of Manet's subject matter: "almost all our originality comes from the stamp that 'time' imprints upon our feelings."[37] When Manet's famous Olympia (1863), a portrait of a nude prostitute, provoked a scandal for its blatant realism mixed with an imitation of Renaissance motifs, Baudelaire worked privately to support his friend, though he offered no public defense (he was, however, ill at the time). When Baudelaire returned from Belgium after his stroke, Manet and his wife were frequent visitors at the nursing home and she would play passages from Wagner for Baudelaire on the piano.[38]

Nadar

Nadar (Félix Tournachon) was a noted caricaturist, scientist and important early photographer. Baudelaire admired Nadar, one of his closest friends, and wrote: "Nadar is the most amazing manifestation of vitality."[39] They moved in similar circles and Baudelaire made many social connections through him. Nadar's ex-mistress Jeanne Duval became Baudelaire's mistress around 1842. Baudelaire became interested in photography in the 1850s and, denouncing it as an art form, advocated its return to "its real purpose, which is that of being the servant to the sciences and arts". Photography should not, according to Baudelaire, encroach upon "the domain of the impalpable and the imaginary".[40] Nadar remained a stalwart friend right to Baudelaire's last days and wrote his obituary notice in Le Figaro.

Philosophy

Many of Baudelaire's philosophical proclamations were considered scandalous and intentionally provocative in his time. He wrote on a wide range of subjects, drawing criticism and outrage from many quarters.

Love

"There is an invincible taste for prostitution in the heart of man, from which comes his horror of solitude. He wants to be 'two'. The man of genius wants to be 'one'.... It is this horror of solitude, the need to lose oneself in the external flesh, that man nobly calls 'the need to love'."[41]

Marriage

"Unable to suppress love, the Church wanted at least to disinfect it, and it created marriage."[41]

The artist

"The more a man cultivates the arts, the less randy he becomes.... Only the brute is good at coupling, and copulation is the lyricism of the masses. To copulate is to enter into another—and the artist never emerges from himself."[41]

Pleasure

"Personally, I think that the unique and supreme delight lies in the certainty of doing 'evil'–and men and women know from birth that all pleasure lies in evil."[41]

"But what can eternity of damnation matter to someone who has felt, if only for a second, the infinity of delight??"

Politics

Along with Poe, Baudelaire named the arch-reactionary Joseph de Maistre as his maître à penser[42] and adopted increasingly aristocratic views. In his journals, he wrote "There is no form of rational and assured government save an aristocracy. A monarchy or a republic, based upon democracy, are equally absurd and feeble. The immense nausea of advertisements. There are but three beings worthy of respect: the priest, the warrior and the poet. To know, to kill and to create. The rest of mankind may be taxed and drudged, they are born for the stable, that is to say, to practise what they call professions."[43]

The public

"In this regards, my friend, you're like the public, to whom one should never offer a delicate perfume. It exasperates them. Give them only carefully selected garbage." [44]

Time

"The will to work must dominate, for art is long and time is brief."[44] (quoting Hippocrates)

"Each man bears within himself his own dose of natural opium, incessantly secreted and renewed, and, from birth to death, how many hours can we count filled with pleasure, with prosperous and effective action?" [44]

Influence

Baudelaire's influence on the direction of modern French (and English) language literature was considerable. The most significant French writers to come after him were generous with tributes; four years after his death, Arthur Rimbaud praised him in a letter as 'the king of poets, a true God'.[45] In 1895, Stéphane Mallarmé published a sonnet in Baudelaire's memory, 'Le Tombeau de Charles Baudelaire'. Marcel Proust, in an essay published in 1922, stated that along with Alfred de Vigny, Baudelaire was 'the greatest poet of the nineteenth century'.[46]

In the English-speaking world, Edmund Wilson credited Baudelaire as providing an initial impetus for the Symbolist movement, by virtue of his translations of Poe.[47] In 1930, T. S. Eliot, while asserting that Baudelaire had not yet received a "just appreciation" even in France, claimed that the poet had "great genius" and asserted that his "technical mastery which can hardly be overpraised ... has made his verse an inexhaustible study for later poets, not only in his own language".[48] Eliot also alluded to Baudelaire's poetry directly in his own poetry. For example, he quoted the last line of Baudelaire's 'Au Lecteur' in the last line of Section I of 'The Waste Land.'

At the same time that Eliot was affirming Baudelaire's importance from a broadly conservative and explicitly Christian viewpoint,[49] left-wing critics such as Wilson and Walter Benjamin were able to do so from a dramatically different perspective. Benjamin translated Baudelaire's Tableaux Parisiens into German and published a major essay on translation[50] as the foreword.

In the late 1930s, Benjamin used Baudelaire as a starting point and focus for his monumental attempt at a materialist assessment of 19th-century culture, Das Passagenwerk.[51] For Benjamin, Baudelaire's importance lay in his anatomies of the crowd, of the city and of modernity.[52] François Porche published a poetry collection called Charles Baudelaire: Poetry Collection in memory of Baudelaire.

In 1982, avant-garde performance artist and vocalist Diamanda Galás recorded an adaptation of his poem The Litanies of Satan (Les Litanies de Satan).

The song "How Beautiful You Are" by The Cure from their 1987 album Kiss Me, Kiss Me, Kiss Me was inspired by and based on Baudelaire's poem "The Eyes of the Poor".[53]

The 1998 Spanglish classic novel Yo-Yo Boing! by Giannina Braschi features a debate between artists and writers on the greatness of Baudelaire versus Arthur Rimbaud and Antonin Artaud.[54]

in 2002, alt-rock band ...And You Will Know Us by the Trail of Dead included a song titled "Baudelaire" on their album Source Tags and Codes.

In 2008, the Italian band Baustelle dedicates to him the song "Baudelaire" on its album Amen.

The 2011 Latin American postcolonial novel "United States of Banana" by Giannina Braschi features cameo appearances by Baudelaire, along with fellow poets Antonin Artaud, Arthur Rimbaud, César Vallejo and Rubén Darío.[55]

The Baudelaires, protagonists of Lemony Snicket's A Series of Unfortunate Events, were named after him.[56]

Vanderbilt University has "assembled one of the world's most comprehensive research collections on ... Baudelaire".[57]

The Japanese comic or manga Aku no Hana, by Shūzō Oshimi, is inspired by Baudelaire's Les Fleurs du mal. The anime was aired in 2013 and drew attention due to its heavy use of rotoscope animation. The protagonist in both manga and the anime, Takao Kasuga, is a bookworm whose favorite book is Les fleurs du mal, translated in Japanese as Aku no Hana.

Les Fleurs du mal has a number of scholarly references.[58]

Works

- Salon de 1845, 1845

- Salon de 1846, 1846

- La Fanfarlo, 1847

- Les Fleurs du mal, 1857

- Les paradis artificiels, 1860

- Réflexions sur Quelques-uns de mes Contemporains, 1861

- Le Peintre de la Vie Moderne, 1863

- Curiosités Esthétiques, 1868

- L'art romantique, 1868

- Le Spleen de Paris, 1869

- Oeuvres Posthumes et Correspondance Générale, 1887–1907

- Fusées, 1897

- Mon Coeur Mis à Nu, 1897

- Oeuvres Complètes, 1922–53 (19 vols.)

- Mirror of Art, 1955

- The Essence of Laughter, 1956

- Curiosités Esthétiques, 1962

- The Painter of Modern Life and Other Essays, 1964

- Baudelaire as a Literary Critic, 1964

- Arts in Paris 1845–1862, 1965

- Selected Writings on Art and Artist, 1972

- Selected Letters of Charles Baudelaire, 1986

- Twenty Prose Poems, 1988

- Critique d'art; Critique musicale, 1992

Musical adaptations

- French composer Claude Debussy set five of Baudelaire's poems to music in 1890: Le Balcon, Harmonie du soir, Le Jet d'eau, Recueillement and La Mort des amants.

- English composer Mark-Anthony Turnage composed settings of two of Baudelaire's poems, "Harmonie du soir" and "L'Invitation au voyage" for soprano and seven instruments.[59]

- French singer-songwriter Léo Ferré devoted himself to set Baudelaire's poetry into music in three albums: Les Fleurs du mal in 1957 (12 poems), Léo Ferré chante Baudelaire in 1967 (24 poems, including one from Le Spleen de Paris), and the posthumous Les Fleurs du mal (suite et fin) (21 poems), recorded in 1977 but released in 2008.

- Soviet/Russian composer David Tukhmanov has set Baudelaire's poem to music (cult album On a Wave of My Memory, 1975).[60]

- Warwickshire poet Siân Lavinia Anaïs Valeriana, artist name The Raveness, is known to adore Baudelaire and written in homage to his work featured on her best selling poetry record 'Of blood and absinthe'(2011) is a poem entitled Sinful Extraordinaire a poem earlier published in her book Lavinia Volume one (2006) ISBN 9781502313966.

- American avant-garde composer, vocalist and performer Diamanda Galás made an interpretation in original French of Les Litanies de Satan from Le Fleurs du Mal, in her debut album titled The Litanies of Satan, which consists of tape and electronics effects with layers of her voice.

- French singer David TMX recorded the poems "Lesbos" and "Une Charogne" from The Flowers of Evil.

- French metal/shoegaze groups Alcest and Amesoeurs used his poetry for the lyrics of the tracks "Élévation" (on Le Secret) and "Recueillement" (on Amesoeurs), respectively. Celtic Frost used his poem Tristesses de la lune as a lyrics for song on album Into the Pandemonium.

- Israeli singer Maor Cohen's 2005 album, the Hebrew name of which translates to French as "Les Fleurs Du Mal", is a compilation of songs from Baudelaire's book of the same name. The texts were translated to Hebrew by Israeli poet Dori Manor, while the music was composed by Cohen himself.

- Italian singer Franco Battiato set Invitation au voyage to music as Invito Al Viaggio on his 1999 album Fleurs (Esempi Affini Di Scritture E Simili).

- American composer Gerard Pape set Tristesses de la lune/Sorrows of the Moon from Fleurs du Mal for voice and electronic tape.

- French band Marc Seberg wrote an adaptation of Recueillement for their 1985 album Le Chant Des Terres.

- Russian heavy metal band Black Obelisk used Russian translations of several Baudelaire poems as lyrics for their songs.

- French singer Mylene Farmer performed "L'Horloge" to music by Laurent Boutonnat on the album" Ainsi soi je" and the opening number of her 1989 concert tour.

- German aggrotech band C-Drone-Defect used the translation of "Le Rebelle" by Roy Campbell as lyrics for the song "Rebellis" on their 2009 album "Dystopia".

- English rock band The Cure used the translation of "Les yeux des pauvres" as lyrics for the song "How Beautiful You Are".

- French singer-songwriter and musician Serge Gainsbourg has set Baudelaire's poem "Dancing Snake" (Le serpent qui danse) to music in his 1964 song "Baudelaire".

- Greek black metal band Rotting Christ adapted Baudelaire's poem "Les Litanies De Satan" from "Fleurs du Mal" for a song of the same name in their 2016 album "Rituals".

- Belgian female-fronted band Exsangue released the debut video for the single "A une Malabaraise" which lyrics is based on Baudelaire’s same-named sonet in 2016.[61]

See also

References

- ↑ "Baudelaire". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ↑ "By modernity I mean the transitory, the fugitive, the contingent which make up one half of art, the other being the eternal and the immutable." Charles Baudelaire, "The Painter of Modern Life" in The Painter of Modern Life and Other Essays, edited and translated by Jonathan Mayne. London: Phaidon Press, 13.

- ↑ Haine, Scott. The History of France (1st ed.). Greenwood Press. p. 112. ISBN 0-313-30328-2. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help); - ↑ Charles Baudelaire, Richard Howard. Les Fleurs Du Mal. David R. Godine Publisher, 1983, p.xxv. ISBN 0-87923-462-8, ISBN 978-0-87923-462-1.

- ↑ Richardson 1994, p. 16

- ↑ Richardson 1994, p. 35

- ↑ Richardson 1994, p. 70

- ↑ Richardson 1994, pp. 67–68

- ↑ Richardson 1994, p. 71

- ↑ Richardson 1994, p. 75

- ↑ Richardson 1994, p. 219.

- 1 2 Richardson 1994, p. 110.

- ↑ Clark, Carol (1995). "Notes on the Text". Selected Poems. By Charles Baudelaire. London: Penguin Books Ltd. p. xxiii. ISBN 978-0-14-044624-1.

- 1 2 Chisholm 1911.

- ↑ Baudelaire, Charles. Les Fleurs du mal. Paris: Revue des Deux Mondes (XXVe année, seconde série de la nouvelle période, tome dixième), 1855. pp. 1079–1093

- ↑ Huneker, James. Introductory preface to: The Poems and Prose Poems of Charles Baudelaire. New York: Brentano's, 1919. p. xvii

- ↑ Richardson 1994, p. 236.

- ↑ Richardson 1994, p. 241.

- ↑ Richardson 1994, p. 231.

- ↑ Richardson 1994, pp. 232–237

- ↑ Richardson 1994, p. 238.

- ↑ Richardson 1994, p. 248

- 1 2 Richardson 1994, p. 250.

- ↑ Richardson 1994, p. 311.

- ↑ Richardson 1994, p. 281.

- ↑ Richardson 1994, p. 400

- ↑ Library.vanderbilt.edu

- ↑ Richardson 1994, p. 268.

- ↑ Baudelaire, Selected writings on art and artists, CUP Archive, 1981, Introduction, p. 17.

- ↑ Richardson 1994, p. 140.

- ↑ Hyslop, Lois Boe (1980). Baudelaire, Man of His Time. Yale University Press. p. 14. ISBN 0-300-02513-0.

- 1 2 Hyslop (1980), p. 68.

- ↑ Hyslop (1980), p. 69

- ↑ Hyslop (1980), p. 131.

- ↑ Hyslop (1980), p. 55.

- ↑ "Music in the Tuileries Gardens". The National Gallery. Retrieved July 13, 2008.

- ↑ Hyslop (1980), p. 53.

- ↑ Hyslop (1980), p. 51.

- ↑ Hyslop (1980), p. 65.

- ↑ Hyslop (1980), p. 63.

- 1 2 3 4 Richardson 1994, p. 50

- ↑ "The Cambridge Companion to Baudelaire". cambridge.org.

- ↑ "Intimate journals :: :: University of Virginia Library". virginia.edu.

- 1 2 3 Baudelaire, Charles. Translated by William H. Crosby, The Flowers of Evil & Paris Spleen, BOA Editions, Ltd., 1991.

- ↑ Rimbaud, Arthur: Oeuvres complètes, p. 253, NRF/Gallimard, 1972.

- ↑ Concerning Baudelaire in Proust, Marcel: Against Sainte-Beuve and Other Essays, p. 286, trans. John Sturrock, Penguin, 1994.

- ↑ Wilson, Edmund: Axel's Castle, p. 20, Fontana, 1962 (originally published 1931).

- ↑ 'Baudelaire', in Eliot, T. S.: Selected Essays, pp. 422 and 425, Faber & Faber, 1961.

- ↑ cf. Eliot, 'Religion in Literature', in Eliot, op. cit., p. 388.

- ↑ 'The Task of the Translator', in Benjamin, Walter: Selected Writings Vol. 1: 1913–1926, pp. 253–263, Belknap/Harvard, 1996.

- ↑ Benjamin, Walter: The Arcades Project, trans. Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin, Belknap/Harvard, 1999.

- ↑ 'The Paris of the Second Empire in Baudelaire' in Benjamin, Walter: Selected Writings Vol. 4 1938–1940, pp. 3–92, Belknap/Harvard, 2003.

- ↑ "Robert Smith and his Books". chainofflowers.com. Rock and Folk Magazine. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- ↑ Yo-Yo Boing!, Introduction by Doris Sommer, Harvard University. Latin American Literary Review Press. 1998. ISBN 0-935480-97-8.

- ↑ United States of Banana. Amazon Crossing. November 2011. ISBN 9781611090673.

- ↑ Kramer, Melody. "A Series Of Unfortunate Literary Allusions". npr.org. NPR. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- ↑ Library.vanderbilt.edu

- ↑ Google Scholar citations

- ↑ cf. The Baudelaire Song Project

- ↑ (Russian) David Tukhmanov

- ↑ cf. Exsangue's "A une Malabaraise" video

-

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Baudelaire, Charles Pierre". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Baudelaire, Charles Pierre". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. - Richardson, Joanna (1994). Baudelaire. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-11476-1. OCLC 30736784.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Charles Baudelaire. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Charles Baudelaire |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Charles Baudelaire |

- Charles Baudelaire's Cats

- The Baudelaire Song Project - Site of The Baudelaire Song Project, a UK-based AHRC-funded academic project examining song settings of Baudelaire's poetry.

- Twilight to Dawn: Charles Baudelaire. Translations, Cordite Poetry Review

- www.baudelaire.cz — Largest Internet site dedicated to Charles Baudelaire. Poems and prose are available in English, French and Czech.

- Charles Baudelaire — Site dedicated to Baudelaire's poems and prose, containing Fleurs du mal, Petit poemes et prose, Fanfarlo and more in French.

- Charles Baudelaire International Association

- Nikolas Kompridis on Baudelaire's poetry, art, and the "memory of loss" (Flash/HTML5)

- baudelaireetbengale.blogspot.com—the influence of Baudelaire on Bengali poetry

- Alexander Barykin — The Invitation to Travel on YouTube

Online texts

- Works by Charles Baudelaire at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Charles Baudelaire at Internet Archive

- Works by Charles Baudelaire at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Charles Baudelaire—Largest site dedicated to Baudelaire's poems and prose, containing Fleurs du mal, Petit poemes et prose, Fanfarlo and more in French.

- Poems by Charles Baudelaire—Selected works at Poetry Archive

- Baudelaire's poems at Poems Found in Translation

- Baudelaire – Eighteen Poems

- "baudelaire in english", Onedit.net—Sean Bonney's experimental translations of Baudelaire (humor)

- Baudelaire, Les Fleurs du Mal and Petits Poèmes en Prose (Le Spleen de Paris), at athena.unige.ch (French)

Single works

- FleursDuMal.org—Definitive online presentation of Fleurs du mal, featuring the original French alongside multiple English translations

- An illustrated version (8 Mb) of Les Fleurs du Mal, 1861 edition (Charles Baudelaire / une édition illustrée par inkwatercolor.com)

- "The Rebel"—poem by Baudelaire

- Les Foules (The Crowds)—English translation