Charles Reade (town planner)

Charles Compton Reade (1880–1933) was a town planner who supported the garden city movement of the early twentieth century.

Born in Invercargill, New Zealand in 1880, Reade became the major figure in disseminating Garden City ideas in Australia. Reade saw the evils of inner city slums while working as a journalist in England and began writing of the need for improved town planning, becoming active in the Garden Cities and Town Planning Association of Great Britain, of which he was acting secretary and editor for its magazine in 1913.

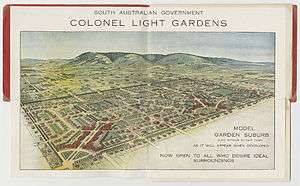

In 1914–15 he led a lecture tour through five Australian States and New Zealand. South Australia appointed Reade as a town planning adviser in 1916 and later he became its first official Town Planner in 1918 and he retained the position until 1920. In 1917 he drew up plans for an Adelaide garden suburb, initially with a working title of Mitcham Garden Suburb and officially named Colonel Light Gardens.

Reade convened Australia's first two town planning and housing conferences in 1917 and 1918. He also twice tried to get town planning legislation through the State legislature: on the first occasion it was defeated by the property-oriented upper House and on the second was passed but was heavily amended by the House.

Reade then left Australia for overseas planning positions, establishing a town planning department in Kuala Lumpur, Malaya in 1921 and moving to Northern Rhodesia in 1929. He committed suicide in South Africa in 1933, only nine days after becoming Chief Planning Officer of Witwatersrand.

Extensive academic study of the life and work of Charles Reade has been conducted by Dr Christine Garnaut of the University of South Australia.

Influence in Australia

Charles Reade was born in 1880 in Invercargill, New Zealand. Reade's childhood involved international travel and education about the conditions of the working class that influenced his later work both as a journalist and his view of the power of good planning to effect improvements in health and enjoyment of life.[1]

Reade became a journalist at the age of 26. He concerned himself with the living and working conditions of the middle class. He strongly believed that good town planning could avoid the overcrowding and disease he saw in his travels in the slums of Manchester, Liverpool and Sheffield. He advocated the eradication of slums to give greater dignity and self-respect to the people who had the misfortune to live there. Reade drew upon the examples of planning in continental Europe, as well as the new garden suburbs designed by Ebenezer Howard, Port Sunlight and Letchworth to show how planning could improve social welfare which had been degraded through industrialization.[2]

Through his writing, Reade became involved in the Garden Cities and Town Planning Association of Great Britain. From 1906 the Association became less fundamentalist about the implementation of Howard's planning principles and more concerned with getting national planning legislation implemented. In 1912, after a year of working in New Zealand, Reade returned to work for the Association. He participated and learnt a lot from the widespread lectures and conferences and pamphlet distribution which occurred during this time.[3] His affable personality and strong work ethic soon brought him to the attention of the Association's officials, and he was chosen, along with W. R. Davidge, for a promotion tour of the new garden city planning movement to Australia and New Zealand in 1914.[4]

In Australia, the general enthusiasm for the Garden City movement began with John Sulman's idea that planning should be about 'convenience, healthfulness and beauty' rather than ad hoc.[5] These principles were embraced after Reade's speeches and conferences during his tour of Australia. Town planning associations began forming rapidly in his wake.[6]

Reade used propagandist techniques learnt with the Garden Cities and Town Planning Association in Britain to great effect.[7] He shocked audiences with examples of the claustrophobic squalor of the slums in industrialised Britain and warned that without implementation of planning law, Australia could also develop these horrific conditions.[8] Reade spoke of the importance of constructing proper housing for the growing population, the evils of unplanned subdivisions outside the city, demarcation of industry and commercial property and planned open spaces.[9] Reade had great foresight as these issues are still as relevant today as they were at the time.

Desiring greater political influence, Reade offered his expertise to the South Australian government and was appointed as advisor in 1915. Later the newly elected Peake government appointed Reade as the first government Town Planner in 1918.[10] During this time Reade was heavily involved in attempting to implement planning legislation and he drafted a Town Planning and Housing Bill in 1916. However, the Legislative Council of South Australia did not pass it, because of both the war and strong opposition from those making profitable investments from no restrictions in place on the use and development of land (Reade 1921, p. 158). On Reade's second attempt in 1920, the legislation was passed after much debate. It established a Government Town Planner with a board of experts and local government representatives, and despite the resistance, is similar to the Reade's original conception (Reade 1921, p. 160). This legislation meant that there could be thoughtful design of suburbs rather than suburbia spreading ad hoc and out of control, at the whim of the money-hungry developer.[11]

Reade was interested in Adelaide primarily because of Colonel William Light's '"brilliant skill and ability in selecting the site and planning the first great city of the reform era in Australia"'.[12] Reade was responsible for many suburb designs in Adelaide and South Australia but one of his major contributions as Government Town Planner of Adelaide was the design of the Mitcham Garden Suburb (later named Colonel Light Gardens). Reade planned this suburb adhering to the Garden City principles while retaining sensitivity to the topography of the land.

The design consisted of many complementary elements: separation of commercial and residential uses, designated recreational space; proximity to existing public transport and provision for an anticipated extension of the tramway; account of the winds and drainage problems; use of a road hierarchy and curvilinear streets to direct traffic away from residential land; appropriate location of schools, aged homes and facilities for returned soldiers; open spaces with many trees and flowers for greater aesthetic appeal and greater width and setbacks on properties to allow for privacy and maximum visibility.[13]

In reviewing the success of the Colonel Light Gardens, Harper (1991) criticises Reade because of the impracticality of the design; especially that he did not translate the garden city principles to the smaller scale of the suburb. For example, Reade included lots for 6 churches and many more civic buildings than one suburb would require. Despite these criticisms, the Colonel Light Gardens are an important legacy of the garden suburb movement in Australia and continue to be a desirable place to live 100 years after their design.[14]

Reade went on to work in Malaya and Northern Rhodesia before committing suicide in South Africa in 1933.[15] Reade was influential in disseminating his planning ideals focussed on slum eradication, Garden City principles and the importance of planning legislation internationally.[16] He strongly believed that good planning could achieve community and individual betterment and aptly referred to himself as a ‘missionary’ able to disseminate ideas of social reforms through planning principles.[17]

Published work

- The Revelation of Britain: A Book for Colonials (Gordon and Gotch, Auckland, 1909)

- Town Planning And Development In The Federated Malay States (1922)

Notes

- ↑ Garnaut 1995, p. 182

- ↑ Garnaut 1995, pp. 181–182

- ↑ Garnaut 1995, p. 183

- ↑ Ward 2005, p. 123

- ↑ Sulman 1921, p. 216

- ↑ Reade 1921, p. 158

- ↑ Garnaut 1995, p. 183

- ↑ Reade 1913, p. 245

- ↑ Garnaut 1995, p. 183

- ↑ Garnaut 1995, p. 186

- ↑ Harper, 1991

- ↑ Garnaut 1995, p. 185

- ↑ Garnaut 1995

- ↑ Harper 1991

- ↑ Ward 2005, p. 124

- ↑ Garnaut 1995, p. 185

- ↑ Garnaut 1995, p. 185

Works cited

- Garnaut, C “Of passion, publicity and planning: Charles Reade and the Mitcham Garden Suburb”, Australian Planner, Vol 35 No 2:181–189. 1995

- Garnaut, C. “Revealing reminiscences Charles Reade from his children’s perspective” Planning History (England) Vol 18 No 2 pp. 20–25. (1996)

- Garnaut, C Colonel Light Gardens: model garden suburb, Crossing Press, Sydney 1999.

- Australian Dictionary of Biography entry for Charles Reade

- Harper, B 1991, 'Colonel Light Gardens—Seventy Years of a Garden Suburb', Australian Planner, vol.29, no.2, pp. 62–69.

- Reade, C 1913, 'A Defence of the Garden City Movement', The Town Planning Review, vol.4, No.3, pp. 245–251.

- Reade, C 1921, 'Town Planning Legislation in South Australia: A Retrospect’, The Town Planning Review, vol.9, no.3, pp. 157–161.

- Sulman, J 1921, ‘The laying out of towns’, An introduction to the study of Town Planning in Australia, William Applegate Gullick, Sydney, pp. 214–216.

- Ward, S 2005, ‘A pioneer ‘global intelligence corps: The internationalisation of planning practice, 1890–1939’, Town Planning Review, vol.76, no.2, pp. 119–141.