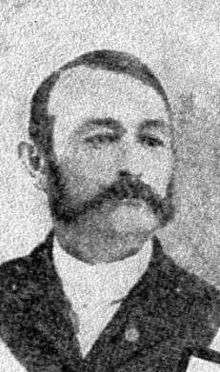

Charles W. Rundle

| Charles W. Rundle | |

|---|---|

Charles Rundle | |

| Born |

December 14, 1842 Cincinnati, Ohio |

| Died |

July 11, 1924 (aged 81) California |

| Place of burial | Los Angeles National Cemetery, Los Angeles, California |

| Allegiance |

United States of America Union |

| Service/branch |

United States Army Union Army |

| Years of service | 1862 - 1865 |

| Rank | Private |

| Unit | 116th Illinois Volunteer Infantry Regiment |

| Battles/wars |

American Civil War • Siege of Vicksburg |

| Awards | Medal of Honor |

Charles W. Rundle (December 14, 1842 – July 11, 1924) was a Union Army soldier in the American Civil War and a recipient of the United States military's highest decoration, the Medal of Honor, for his actions during the Siege of Vicksburg.

He was born in Kentucky and fought on the side of the Union during the American Civil War. While fighting in Vicksburg he, along with 150 others attempted to stop a Confederate assault, only to be pinned down. They continued to resist confederate attacks until nightfall and Rundle and a few others managed to escape.

After the war he became a farmer in Colorado and started a family. While living in Grand Junction he was arrested he resisted a city marshal attempts to capture his dog, but was found not guilty of interfering with a city marshal. He sold his farm in 1902 and worked in the Grand Junction Post Office until retiring in 1919. After retiring they moved to southern California attempting to improve his wife's health. He and his wife, Hettie, lived in an old soldiers' home until they died and were buried side-by-side at the Los Angeles National Cemetery.

Early life and military service

Rundle was born in Kentucky on December 14, 1842.[1][2] He joined the Army from Oakley Township, Illinois in August 1862, and by May 22, 1863, was serving as a private in Company A of the 116th Illinois Volunteer Infantry Regiment.[3] On that day, near Vicksburg, Mississippi, Union commanders called for 150 unmarried volunteers to charge a heavily fortified Confederate position; Rundle answered the call. The volunteers were to build makeshift bridges across the trench immediately in front of the fortifications and then place ladders against the walls of the position. They would be followed by a large Union force which would used the newly placed bridges and ladders to storm the fort. The prospects for the volunteers were grim, and the group was accordingly known as the "forlorn hope".[1]

As Rundle and the others ran across the open ground in front of the fort, Confederate cannons opened fire and inflicted heavy casualties. The group was sent into disarray and efforts to continue the mission were abandoned. Rundle and the other members of the advance party sought cover in the trench at the base of the fort walls. The Confederates, unable to lower the aim of their cannons enough to fire into the Union soldiers, began lighting cannonballs and tossing them by hand into the trench. The fuses proved to be too long, however, and the Union soldiers were able to jump out of harm's way before they exploded. Some of the men, including Rundle, began picking up the lit cannonballs and throwing them back at the Confederates. The soldiers remained trapped until nightfall, when Rundle and others were able to escape back to the Union lines; only 30 of the original 150 men made it back.[1] For these actions, he was awarded the Medal of Honor several decades later, on July 26, 1894. His official citation reads

Gallantry in the charge of the 'volunteer storming party'.[3]

Later life and death

After the war, Rundle moved to Colorado and owned a farm east of Grand Junction. He eventually married and, with his wife Hettie, had four daughters and two sons; one of his sons died in a 1905 railroad accident. Rundle sold his farm in 1902 and worked for the Grand Junction Post Office until his retirement in 1919. He was an active member of the Elks and the Grand Army of the Republic.[1]

In 1893, he was involved in a dispute with the Grand Junction city government regarding his dog. On May 27 of that year, Rundle was arrested after knocking away the snare of a city marshal who was attempting to capture the dog in accordance with a recently passed leash law. The case went to trial, with Rundle's lawyer arguing that the animal had been under the control of its owner at all times, and that the marshal had exceeded his authority by calling the dog over in order to snare it. The jury quickly found Rundle not guilty of interfering with a city marshal.[1]

Following his retirement, Rundle and his family moved to southern California in the hopes that the climate would be beneficial to his wife's health. He and his wife, Hettie, lived in an old soldiers' home; Rundle died there in 1924, at age 81, and Hettie in 1931. They were buried side-by-side at the Los Angeles National Cemetery.[1]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Brewer, Garry (November 23, 2009). "The 2nd Battle of Forlorn Hope in GJ". Grand Junction Free Press. Grand Junction, Colorado. Archived from the original on April 12, 2010.

- ↑ "Charles W. Rundle (1842 - 1924)". Find a Grave. March 6, 2002. Retrieved April 12, 2010.

- 1 2 "Civil War Medal of Honor recipients (M–Z)". Medal of Honor citations. United States Army Center of Military History. August 3, 2009. Retrieved April 12, 2010.

External links

- "Charles W. Rundle". Hall of Valor. Military Times. Retrieved April 14, 2010.