Charlie Getzein

| Charles Getzein | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

1889 S.F. Hess baseball card for Getzein | |||

| Pitcher | |||

|

Born: February 14, 1864 Germany | |||

|

Died: June 19, 1932 (aged 68) Chicago | |||

| |||

| MLB debut | |||

| August 13, 1884, for the Detroit Wolverines | |||

| Last MLB appearance | |||

| July 19, 1892, for the St. Louis Browns | |||

| MLB statistics | |||

| Win–loss record | 145-139 | ||

| Earned run average | 3.46 | ||

| Strikeouts | 1,070 | ||

| Teams | |||

| |||

| Career highlights and awards | |||

| |||

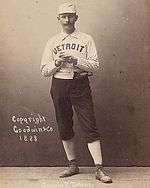

Charles H. Getzein (sometimes spelled Getzien) (February 14, 1864 – June 19, 1932) was an American professional baseball player from 1883 to 1891. He played all or parts of nine seasons in Major League Baseball with four different National League teams from 1884 to 1891. He was the first German in MLB history

Getzein was known by the nickname "Pretzels". Sources conflict as to whether the nickname was derived from his German ethnicity or from the belief that he was able to throw a "double curve" following "the curves of a pretzel." During nine major league seasons, Getzein compiled a 145-139 win-loss record and a 3.46 earned run average (ERA). He threw 277 complete games, a total that ranks 58th in major league history. Only three pitchers threw more complete games in major league careers shorter than Getzein's nine-year career.

Getzein had his most extensive playing time with the Detroit Wolverines, compiling records of 30-11 and 29-13 in 1886 and 1887. In the 1887 World Series (which Detroit won, 10 games to 5), Getzein pitched six complete games and compiled a 4-2 record with a 2.48 ERA. He also won 23 games for the Boston Beaneaters in 1890.

Early years

Getzein was born in 1864, but sources are in conflict as to whether he was born in Chicago or Germany.[1][2] Getzein began playing baseball as a boy in Chicago.[2] He played as an amateur in the Chicago City League.[3]

Professional baseball

The "Pretzel Curve"

During his career, Getzein's drew acclaim for his curveball. Getzein's version of the pitch was sometimes referred to as the "pretzel curve."[2][4] Sporting Life described Getzein's unusual delivery as follows: "In delivering his 'pretzels' 'Getz' faces third base with one foot in either corner of the lower end of the box. Bending the left knee slightly, he draws his right arm well back. Then, straightening up quickly, he slides the left foot forward with a characteristic little skip, and, bringing his arm around with a swift overhand swing, drives the ball in at a lively pace."[2]

After a Getzein victory over the Kansas City Cowboys in 1886, the Detroit Free Press wrote: "The Pretzel is all right. He went into the box to-day and pitched one of his finest, his curves circling around in the form of the delicious pastry from which Getz takes his sobriquet."[5] However, the editor of the Grand Rapids World opined that Getzein's "curved ball" was a fiction. He wrote:

"The baseball enthusiasts claim for Getzein that he is able to so pitch a ball that it will describe the arc of a circle on a horizontal plane before reaching the catcher, and that therein lies the secret of his marvelous pitching . . . Scientifically, this theory is utterly absurd. The forces that act upon a ball pitched by Getzein are not different from those which operate upon a projectile thrown from any other source, and the results must be the same, and governed by the same laws. The curves are in the imagination of Getzein's admirers. When the ball leaves his hand it is beyond his control, and it moves forward from the impulse last given it as it leaves his hand. It is then controlled by the force of propulsion, the resistance of the atmosphere, and gravitation. . . . Getzein's antic and deceptive motions may deceive the batter, so that he is unable to discover the exact course of the ball in time to strike it, but he cannot throw a ball so as to make a curve on the horizontal plane."[6]

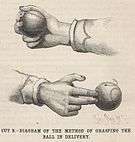

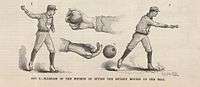

The Scientific American magazine responded in July 1886 by publishing an article written by Henry Chadwick (accompanied by several diagrams, two of which are reproduced above) explaining the physics behind the curve ball pitch.[6]

In 1891, O. P. Caylor in Outing magazine examined "The Theory and Introduction of Curve Pitching" and noted that many "ignorant ball players" had believed that Getzein was capable of throwing a "double curve."[7] Caylor deemed the "double curve" to be "an ocular delusion", but claimed that Getzein's nickname was based on the delusion: "[W]e have the nickname of 'the Pretzel Pitcher,' given to Getzein by players who imagine the curve from his hands comes at them with the curves of a pretzel."[7]

Getzein was known by the nickname "Pretzels". Sources conflict as to whether the nickname was derived from his German ethnicity or from the belief that he was able to throw a "double curve" following "the curves of a pretzel."[7]

Grand Rapids

Getzein was listed at 5 feet, 10 inches, and 172 pounds, and he batted and threw right handed.[1] In 1882, Getzein made his professional baseball debut with the Grand Rapids, Michigan, team in the Northwestern League.[2][3] According to an account published in The Sporting News, he "pitched his puzzling twisters and curves in the Northwestern League while that organization was in existence."[2]

During the 1884 season, Getzein started and completed 30 games, and threw 11 shutouts, for Grand Rapids, compiling a record of 27–4 win–loss record with a 0.52 earned run average (ERA).[8]

Detroit Wolverines

On August 9, 1884, the Grand Rapids team was dropped from the Northwestern League and disbanded. Jack Chapman, manager of the Detroit Wolverines, seized the opportunity to sign five former Grand Rapids players, including "what is known as the 'G' battery -- Getzein and Gastfield."[9] The Detroit Free Press reported that Getzein "has been a formidable man to face in the Northwestern League, in one instance striking out sixteen batters."[9]

Getzein made his major league debut at Detroit's Recreation Park on August 13, 1884. Getzein faced Cleveland and did not allow an earned run. The Detroit Free Press took note of Getzein's performance:

"Getzien caused the Cleveland batters to pound the air thirty-seven times, and eleven more strikes were called. It is a great record, and one that is seldom equaled. He had great speed at the outset, and struck out six of the first eight men who came to the bat. He could not maintain the pace, however, and was not so effective in the latter portion of the game, but was sufficiently so to prevent any one from earning a run."[10]

Despite Getzein's pitching performance, Detroit lost the game by a 1–0 score as Cleveland scored an unearned run.[10] Getzein went on to start (and complete) 17 games for the Wolverines during the remaining two months of the 1883 season. He posted a 5–12 record for a Detroit team that finished in last place in the National League with a 28–84 record, 56 games out of contention.[11] Getzein provided one of the few highlights for the 1884 Wolverines, pitching a six-inning no-hitter against the Philadelphia Phillies on October 1, 1884.[12] The Detroit Free Press reported on Getzein's no-hitter as follows:

"When Spalding compiles the history of remarkable games for his Guide for 1885, it will embrace the fact that in the Detroit-Philadelphia game of October 1 Getzien, the Detroit pitcher, was not batted for a base – a feat seldom accomplished. It should contain further fact that of eighteen men at bat he struck out ten, and of the other eight but one hit the ball beyond the diamond – Purcell, in the first inning, a fly to Weidman. Of the other seven, only three hit to the diamond, or a total of four balls struck inside the foul lines. Of the eighteen, [Detroit catcher] Gastfield put out eleven and threw out three others, Bennett, Scott and Weidman each had a fly, and Jones threw one out at first."[13]

Getzein finished the 1884 season with a 1.95 ERA, third best in the National League behind Old Hoss Radbourn (1.38) and Charlie Sweeney (1.95), both of whom played for the league champion Providence Grays.[14]

Over the course of the full 1884 season, pitching for both Grand Rapids and Detroit, Getzein started and completed 47 games and pitched 423-1/3 innings.[1][8]

In 1885, Getzein compiled a 12–25 record as his ERA jumped to 3.03.[1] His record in 1885 was again impacted by playing with an noncompetitive team. The 1885 Wolverines finished the season in sixth place with a 41–67 record.[15]

In 1886, Getzein and the Wolverines saw their fortunes rise as the Wolverines assembled one of the best hitting teams in National League history featuring, among others, Dan Brouthers, Sam Thompson, Hardy Richardson, and Jack Rowe. Despite having a 3.03 ERA (precisely the same as his 1885 performance), Getzein won a career-high 30 victories against 11 losses.[1] Getzein was not the Wolverines' leading pitcher in 1886, as teammate Lady Baldwin led the National League with 42 wins. The 1886 Wolverines finished in second place, 2½ games behind the Chicago White Stockings, with an 87–36 record and a .707 winning percentage.[16]

In 1887, Getzein was the leading pitcher on a Detroit Wolverines team that won the National League pennant and then defeated the St. Louis Browns in the 1887 World Series.[17] Getzein compiled a 29–13 record and a 3.73 ERA, leading the league in winning percentage (.690) but also in home runs allowed (24).[1] In September 1887, a group of influential fans in Detroit contributed money to purchase "an elegant two hundred dollar gold watch and chain" for Getzein to express their admiration for Getzein's "magnificent work for the club."[18]

In the 1887 World Series (which Detroit won, 10 games to 5), Getzein pitched six complete games and compiled a 4–2 record with a 2.48 ERA.[1] On October 17, 1887, Getzein pitched a no-hitter through the first eight innings in Game 10 of the World Series played before 10,000 spectators at the Polo Grounds in New York. The Detroit Free Press wrote: "Getzien made a remarkable showing. Up to and including the eighth inning only twenty-seven men went to the bat and not a clean hit had been scored. Not till the ninth did the world beaters succeed in getting a hit, and then they failed to score the much desired run."[19]

In 1888, Getzein compiled an 18–22 record and a 3.05 ERA. He started 46 games and completed 45 of them with 404 innings pitched.[1] However, Getzein lost his role at the team's leading pitcher, as Pete Conway compiled a 30–14 record and a 2.25 ERA for the 1888 Wolverines.[20] After Getzein gave up 10 runs in an August 1888 game against Washington, the Detroit Free Press dubbed him the "Pulverized Pretzel."[21] The newspaper reported: "The Detroits were defeated again to-day ... simply because Getzein could not keep the ball away from the Senatorial bat. When he pitched high they hit it. When he delivered his famous drop, he was knocked out of the lot, and his in and out curves were as big as balloons to Ted Sullivan's men."[21] As the 1888 season progressed, relations between Getzein and the Detroit manager became strained. After a game in which Getzein gave up 21 hits against Boston, The Sporting Life reported on speculation that Getzein may have intentionally thrown the game:

"The Getzein episode makes Detroiters weary. The Bostons have no license to make 21 hits off the Pretzel when he pitches his game. Either he was not in condition to pitch or he didn't try to. . . . If the latter, and he repeated his performance against the Kansas Citys a few years ago, when he deliberately tossed the balls to the plate and permitted the Cowboys to make 13 runs in one inning, why no one here would mourn much if he was fined to the limit. What the merits of his quarrel with Watkins are of course are not known here. But Getzein is inclined to be very free with his tongue. Considering his fine treatment here it is time for him to get over his childish humors and do the best he knows how whenever called on."[22]

Later years

Getzein's career with the Wolverines ended after the 1888 season. On March 5, 1889, he was sold by Detroit to the Indianapolis Hoosiers.[1][23] During the 1889 season, he compiled an 18–22 record and a 4.54 ERA for the Hoosiers and led the National League in home runs allowed with 27.[1]

After a sub par season with the Hoosiers, Getzein was acquired by the Boston Beaneaters in March 1890. He returned to good form in 1890, compiling a 23–17 record with a 3.19 ERA for the fifth-place Beaneaters.[1] While pitching for Detroit in 1887, Getzein was teamed up with catcher Charlie Ganzel, and the pair became known as the "Pretzel Battery" because of their shared German ethnicity.[24][25] When Getzein signed with Boston in 1890, he was reunited with Ganzel. The Sporting Life reported: "The signing of Getzein by the Boston League Club re-unites the famous 'Pretzel Battery,' Getzein and Ganzel, of the Detroit ex-champions."[26]

Getzein began the 1891 season with Boston, but he was released by the team on July 16, 1891, after compiling a 4–5 record in nine starts. He attempted a comeback with the Cleveland Spiders in August 1891,[27] but he appeared in only one game for the Spiders, allowing nine runs in nine innings. He concluded his major league career appearing in 13 games for the St. Louis Browns in 1892.[1]

In 1894, Getzein was reported to be playing first base for a Chicago City League team.[28]

Career statistics

During nine major league seasons, he compiled a 145–139 record and a 3.46 earned run average (ERA) in 296 games. He totaled 292 games started and threw 277 complete games,[1] a total that ranks 58th in major league history. Only three pitchers in major league history (Ed Morris, Mark Baldwin, and Hall of Famer Albert Spalding) threw more complete games in careers shorter than Getzein's nine-year career.[29]

Getzein's record for complete games is based in part on the customs of the 1880s. In 1915, Baseball Magazine reported that managers were not allowed to freely pull the starting pitcher from a game in the bygone era. It cited an incident involving Getzein to illustrate the old practice:

"The Nationals got onto Getzein in the fourth inning and batted him all over the field. In the fifth inning they kept up the slugging until Getzein said he was ill, and Manager Hanlon wanted the Nationals to allow Getzein to retire, claiming that he was too sick to play. Baker, captaining the home club, said he would call a doctor and have him examine Getzein, and if the latter was really sick he would probably allow the change to be made. Dr. Bond, who happened to be present, was called on, and he examined the pitcher, while the crowd guyed Getzein terribly. The doctor announced that he did not consider Getzein sick, only discouraged at the pounding he had received, and that he would be able to finish the game."[30]

Family and death

Getzien was married to Rose Dibble.[31] He died in June 1932 after suffering a heart attack at his home in Chicago.[32] He was buried at Concordia Cemetery in Forest Park, Illinois.[1][33]

See also

Sources

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 "Pretzels Getzien Statistics and History". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved February 28, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Sketch of the Men Who Now wear the Dauvray Medals" (PDF). The Sporting Life. 1887.

- 1 2 "Death's Doing: Edward Gastfield, Once a Well-Known Catcher, Joins the Great Silent Majority" (PDF). The Sporting News. December 16, 1899. p. 3.

- ↑ "Notes and Comments" (PDF). The Sporting Life. July 21, 1886. p. 3.("Getzein's 'pretzel curves' are again effective, now that he is through with the Chicagos for a while.")

- ↑ "Getzien Goes In: Our Sturdy German Twirler Does Good Work at Kansas City; The Cowboys Unable to Size Up His Drops and Curves". Detroit Free Press. September 15, 1886. p. 8.

- 1 2 Henry Chadwick (July 31, 1886). "The Art of Pitching in Baseball". Scientific American. pp. 71–72.

- 1 2 3 O. P. Caylor (August 1891). "The Theory and Introduction of Curve Pitching" (PDF). Outing.

- 1 2 "Pretzels Getzien Minor League Statistics". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved July 28, 2014.

- 1 2 "Sporting Matters: Chapman Engages Five Players of the Disbanded Grand Rapids Team". Detroit Free Press. August 12, 1884. p. 8.

- 1 2 "Sporting Matters: Detroit's Weak Batting Team Shut out by the Cleveland Team". Detroit Free Press. August 14, 1884. p. 3.

- ↑ "1884 Detroit Wolverines". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved February 28, 2013.

- ↑ "Charlton's Baseball Chronology - 1884". BaseballLibrary.com. Retrieved February 28, 2013.("October 1 Charlie Getzein (Detroit NL) hurls a 6-inning no-hitter against Philadelphia‚ winning‚ 1–0.")

- ↑ "Sporting Matters: Getzien and Gastfield, With a Little Aid, Play a Wonderful Game; Not a Philadelphian Batting for even the Semblance of a Base". Detroit Free Press. October 2, 1884. p. 7.

- ↑ "1884 National League Pitching Leaders". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved February 28, 2013.

- ↑ "1885 Detroit Wolverines". baseball-reference.com. Retrieved February 28, 2013.

- ↑ "1886 Detroit Wolverines". baseball-reference.com. Retrieved February 28, 2013.

- ↑ "1887 Detroit Wolverines". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved February 28, 2013.

- ↑ "Getzein in Luck: Detroit to Reward Him for His Faithful Work" (PDF). The Sporting Life. September 7, 1887. p. 1.

- ↑ "The Browns Whitewashed: Getzien Holds the World Beaters Down to Three Actual Hits". Detroit Free Press. October 17, 1887. p. 5.

- ↑ "1888 Detroit Wolverines". baseball-reference.com. Retrieved February 28, 2013.

- 1 2 "A Pulverized Pretzel: The Senators Make Getzein Extremely Weary; And the Champions Lose Their Eight Straight Game". Detroit Free Press. August 8, 1888. p. 8.

- ↑ "Detroit Speculations" (PDF). The Sporting Life. June 20, 1888. p. 1.

- ↑ "Sporting Notes". Detroit Free Press. March 12, 1889. p. 3.("Pretzel Getzien will pitch for Indianapolis next season. When Getz loses his head among the Hoosiers a circus with six rings will ensue.")

- ↑ "The Ballplayers – Charlie Getzien". BaseballLibrary.com. The Idea Logical Company, Inc. Retrieved February 28, 2013.

- ↑ "Baseball's Honor Roll Has Famous Batteries". Detroit Free Press. September 12, 1909. p. 16.("A noted team of bygone days was composed of Getzein and Ganzel -- the pretzel battery they were called when they played for the Detroits in 1887. The alliteration perhaps helped in keeping them before the public as a battery, but of course only slightly as compared to their usefuleness.")

- ↑ "Notes and Gossip" (PDF). The Sporting Life. April 5, 1890. p. 3.

- ↑ "Cleveland's Club: Pitcher Getzein Likely to Be Signed – No Other Changes" (PDF). The Sporting Life. August 8, 1891. p. 1.

- ↑ "Editorial Views, News, Comment" (PDF). The Sporting News. May 19, 1894. p. 3.

- ↑ "Career Leaders & Records for Complete Games". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved February 28, 2013.

- ↑ William A. Phelon (October 1915). "Baseball Customs Past and Present" (PDF). Baseball Magazine. p. 56.

- ↑ "Death Notices". Chicago Daily Tribune. June 21, 1932. p. 12.

- ↑ "Getzein, Baseball Veteran Dies". The New York Times. June 21, 1932.

- ↑ "Hold Funeral Tomorrow for Getzien, Former Tiger". Chicago Daily Tribune. June 21, 1932. p. 19.