Chiclet keyboard

.jpg)

A chiclet keyboard, or island-style keyboard, is a type of input device for electronic systems such as personal computers, calculators and remote controls that uses keys in the shape of small squares with rounded corners and straight sides, in the style of Chiclets, an American chewing gum brand. A perforated bezel fills the gaps between the keys.[1]

The term has changed meaning in recent years. During the first home computer boom of the 1980s, a chiclet keyboard was synonymous with cheap quality and a poor user experience. Nowadays, the term is neutral and refers to low-profile, low-travel keyboards with simplified, flat bezel-separated keycaps that other than their appearance function like contemporary computer keyboards.

History

The term first appeared during the home computer era of the late 1970s to mid-1980s. The TRS-80 Color Computer,[2] TRS-80 MC-10,[3] and Timex Sinclair 2068[4] were all described as having "chiclet keys".

This style of keyboard was met with poor reception. John Dvorak wrote that it was "associated with $99 el cheapo computers".[5] The keys on Sinclair ZX Spectrum computers were "rubber dome keys" which were sometimes described as "dead flesh",[6] while the feel of the IBM PCjr's chiclet keyboard was reportedly compared to "massaging fruit cake".[7] Its quality was such that an amazed Tandy executive, whose company had previously released a computer with a similarly unpopular keyboard, asked "How could IBM have made that mistake with the PCjr?"[8]

Two decades later the term instead describes low-profile, low-travel scissor keyboards with simplified, flat keycaps separated by a bezel. Sony was the first modern laptop manufacturer to make use of this keyboard style with the release of the VAIO X505 in 2004.[9]

Design

The underlying technology used by such keyboards varies considerably. In some cases the keys themselves are integral to the backing membrane and deform when pressed to complete an electrical contact, while in other cases the keys have individual low-travel scissor switches.

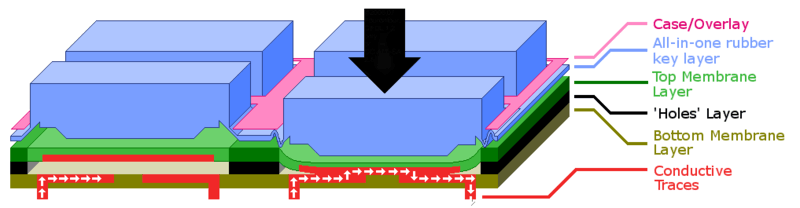

In some versions of the chiclet keyboard, the bottom three layers are essentially the same as those in the membrane keyboard. In both cases, a keypress is registered when the top layer is forced through a hole to touch the bottom layer. For every key, the conductive traces on the bottom layer are normally separated by a non-conductive gap. Electric current cannot flow between them; the switch is open. When pushed down, conductive material on the underside of the top layer bridges the gap between those traces; the switch is closed, current can flow, and a keypress is registered.

Unlike the membrane keyboard, where the user presses directly onto the top membrane layer, this form of chiclet keyboard places a set of moulded rubber keys above this. With some key designs, the user pushes the key, and under sufficient pressure the thin sides of the rubber key suddenly collapse. In other designs — such as that seen in the diagram — the deliberate weak point is where the key joins the rest of the sheet. The effect is similar in both cases. This collapse allows the solid rubber center to move downwards, forcing the top membrane layer against the bottom layer, and completing the circuit. The "sudden collapse" of the chiclet keyboard (along with the movement of the key) provides a greater tactile feedback to the user than a simple flat membrane keyboard.

Simplified design

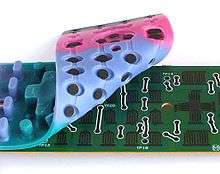

Other versions of the chiclet keyboard omit the upper membrane and hole/spacer layers; instead the underside of the rubber keys themselves have a conductive coating. When the key is pushed, the conductive underside makes contact with the traces on the bottom layer, and bridges the gap between them, thus completing the circuit. Grooves between hollow domes on the underside permit air to flow out of a dome when a key is pressed, and let air come back in when released.

The dome switch keyboards used with a large proportion of modern PCs are technically similar to chiclet keyboards. The rubber keys are replaced with rubber domes, and hard plastic keytops rest on top of these. Because the keytops are wider than the rubber domes the keytops are not separated but align almost perfectly with only a minimal gap in between each other.

List of early computers with chiclet keyboards

All of the computers listed hail from the early home computer era, except the OLPC XO-1.

- Atari Portfolio (its keys resembled those of a HP pocket calculator)

- AT&T Sceptre Videotex terminal

- Cambridge Z88 (arguably a mix between a membrane and chiclet keyboard)

- Commodore PET 2001 (the original 1977 PET had the square keys of a calculator or cash register)

- Commodore 116 (version of the C16 sold only in Europe)

- Enterprise 64 (had a rubber keyboard, on top of which plastic keycaps were glued)

- IBM PCjr[10]

- Jupiter ACE (Sinclair spectrum style black rubber keys)

- Mattel Aquarius (blue rubber keys)

- Microdigital TK90X (Brazil ZX Spectrum derivation)

- Multitech Microprofessor I (MPF 1) and MPF II (the latter an early Apple II compatible)

- OLPC XO-1 (green rubber keys molded from a single sheet of rubber)

- Oric-1 (hard key tops glued on a rubber sheet, somewhat resembling the PCjr)

- Panasonic JR-200

- Rabbit RX83 very similar to MC-1000 and GEM-1000

- Sinclair ZX Spectrum 16/48K (later models had slightly improved keyboards)

- Spectravideo SV-318

- Tandy TRS-80 Color Computer I (later 'CoCo's had full-travel keyboards)

- Tandy TRS-80 MC-10 and its French counterpart, the Matra Alice

- Texas Instruments TI-99/4 (predecessor of the TI-99/4A, which had a full-travel keyboard)

- Thomson MO5 (French microcomputer based on the 6809 microprocessor)

- Timex Sinclair 1500 (U.S. ZX81 derivation)

- Timex Sinclair 2068 (U.S. ZX Spectrum derivation)

- VTech Laser 200 (also known as the Video Technology VZ200)

- Some early models of MSX computers, for example the Philips VG-8010[11]

See also

References

- ↑ "So what is a ‘chiclet’ keyboard anyway?", Netbook Choice, 9 April 2009.

- ↑ "The Coco Chronicles"

- ↑ The TRS-80 MC-10: too little, too late for too much? (evaluation). Owen W. Linzmayer, Creative Computing Vol. 9, No. 10. October 1983. 39

- ↑ "The Timex-Sinclair 2068. (evaluation)". Owen W. Linzmayer, Creative Computing Vol. 10, No. 3. March 1984. p. 93. (atarimagazines.com).

- ↑ Dvorak, John C. (1983-11-28). "Inside Track". InfoWorld. p. 188. Retrieved 23 March 2016.

- ↑ "Sinclair ZX Spectrum". ComputerMuseum.50megs.com.

- ↑ Sandler, Corey (1984-02-21). "A Secret Inside The ROM". PC Magazine. p. 323. Retrieved 24 October 2013.

- ↑ "FROM HOME TO BUSINESS: THE ECLECTIC RADIO SHACK COMPUTER LINE". InfoWorld. 1984-08-20. pp. 47–52. Retrieved May 26, 2011.

- ↑ "What the Vaio Z says about Sony's little design problem".

- ↑ "Chicklet Keyboard frm IBM PC Jr". DigiBarn Computer Museum.

- ↑ "Philips VG 8000 / 8010". oldcomputers.com History of Home and Game Computers. Erik Klooster.

- This article is based on material taken from the Free On-line Dictionary of Computing prior to 1 November 2008 and incorporated under the "relicensing" terms of the GFDL, version 1.3 or later.