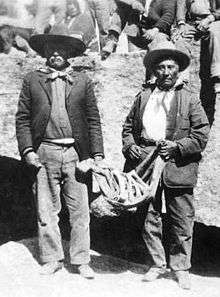

Ouray (Ute leader)

Ouray (Arrow) (c. 1833–August 24, 1880);(August 20, 1880 according to whites based out of Colorado) was a Native American chief of the Uncompahgre band of the Ute tribe, then located in western Colorado. Because of his leadership ability, Ouray was also acknowledged by the United States government as a chief of the Ute.

In 1880 he left Colorado to travel to Washington, D.C., where he testified before Congress about the Ute uprising of 1879. He tried to secure a treaty for the Uncompahgre Ute, who wanted to stay in Colorado; but, the following year, the United States forced the Uncompahgre and the White River Ute to the west to reservations in present-day Utah. The reason he was called the man of peace was because he made a treaty with the settlers.

Biography

Early life and education

Ouray was born in what is now New Mexico. According to oral history, he was born on a clear night of November 13, 1833, during the Leonid meteor showers, which was taken as an omen. In Ute, ouray means “the arrow,” drawn from the meteor shower that occurred at the time of his birth. His father, Guera Murah, was a Jicarilla Apache adopted into the Ute, and his mother was an Uncompahgre Ute. He learned Spanish, English, and later both the Ute and Apache languages, which he found helpful in negotiating treaties.[1]

Marriage and family

Ouray's first wife, Black Water, died soon after the birth of their only child, a boy named Queashegut, called Parso (apple) by his father because of his round, dimpled face. After the death of his wife, Ouray married Chipeta, "White Singing Bird" in the Ute language, then sixteen. When Queashegut was five years old, Ouray took him along on a buffalo hunt. Their hunting camp, near present-day Fort Lupton, was attacked by Sioux warriors and Queashegut was abducted. Ouray never saw his son again and remained in deep grief, trying to find him for the rest of his life. According to a 1924 article in the Denver Post, "The parents never saw or heard from their only child again. They said he was dead rather than believe the probable truth, he lived with their enemies and was raised to fight against his own."[2]

Ten years after the abduction, Felix Brunot, from the U.S. Commissioner of Indian Affairs, wanting Ouray to turn over valuable mining property lured Ouray with the promise of finding his son. However, instead, Ouray was presented a 17-year-old orphan brought to meet Ouray and Chipeta in Washington, D.C. “" meeting turned out quite dissatisfying for Ouray," according to tribal historians. However, Richard E. Wood, author of the book, Here Lies Colorado, writes, "Although he was disappointed with the outcome, Ouray was impressed by the effort the government made." In 1874, with Ouray’s help, the Brunot Agreement was ratified and with Ouray's help the United States acquired the mineral-rich property they had been seeking.[3]

Becoming chief

At about age 18, Ouray came to modern-day Colorado to be a member of the Tabeguache (Uncompahgre) Ute band, where his father was already a leader. He spent much of his youth working for Mexican sheepherders, but fought both the Kiowa and the Sioux while living among the Tabeguache. At his father's death in 1860, Ouray became chief of the band, at the age of 27.

Although Ouray sought reconciliation between peoples, with the belief that war with the whites likely meant the demise of the Ute tribe, other, more militant Utes, considered him a coward and called him The White Man's Friend. Ouray never cut his long Ute-fashion hair, though he often dressed in the European-American style.

The U.S. government appointed a commission to determine a reservation for the Ute. Members were Alfred B. Meacham, former U.S. Superintendent of Indian Affairs for Oregon; Otto Mears, a railroad executive, and George W. Manypenny, former Commissioner of Indian Affairs. About the time that the government established the White River Indian Agency in western Colorado, the government recognized Ouray as chief of the Uncompahgre. The White River Ute had separate leaders. Ouray and others traveled to Washington, DC to consult on the reservation. When President Rutherford B. Hayes met Ouray in 1880 in Washington, DC, he said that the Ute was "the most intellectual man I've ever conversed with."[4] Ouray also met President Ulysses S. Grant.

Death

Ouray died in August 24, 1880 near Los Pinos Indian Agency in Colorado. His people secretly buried him near Ignacio, Colorado. Forty-five years later, in 1925, his bones were re-interred in a full ceremony led by Buckskin Charley and John McCook at the Ignacio cemetery.

A 1928 article in the Denver Post reads, "He saw the shadow of doom on his people" and a 2012 article writes, " He sought peace among tribes and whites, and a fair shake for his people, though Ouray was dealt a sad task of liquidating a once-mighty force that ruled nearly 23 million acres of the Rocky Mountains."[5]

Legacy and honors

Ouray's obituary in The Denver Tribune read:

“In the death of Ouray, one of the historical characters passes away. He has figured for many years as the greatest Indian of his time, and during his life has figured quite prominently. Ouray is in many respects...a remarkable Indian...pure instincts and keen perception. A friend to the white man and protector to the Indians alike.”

- Ouray County and its county seat, the town of Ouray in Colorado are named for him.

- Mount Ouray in the Sawatch Mountain Range and Ouray Peak in Chaffee County, both in Colorado, were named for him.

- Camp Chief Ouray, located in Granby, Colorado.

References

- ↑ http://blogs.denverpost.com/library/2012/08/13/chief-ourays-acclaim-underpinned-search-sorrow-kidnapped-apple/3107/

- ↑ http://blogs.denverpost.com/library/2012/08/13/chief-ourays-acclaim-underpinned-search-sorrow-kidnapped-apple/3107/

- ↑ http://blogs.denverpost.com/library/2012/08/13/chief-ourays-acclaim-underpinned-search-sorrow-kidnapped-apple/3107/

- ↑ http://www.sanjuansilverstage.com/07heritage/native/ute/ute_chief_ouray.html

- ↑ http://blogs.denverpost.com/library/2012/08/13/chief-ourays-acclaim-underpinned-search-sorrow-kidnapped-apple/3107/

Further reading

- H. Bert Jenson, "Chipeta: Glory and Heartache", The Outlaw Trail Journal, n.d., Salt Lake City, Utah, on Utah State University, Unintah Basin Education Center Website

- Grant, Bruce. The Concise Encyclopedia of the American Indian 3rd ed., Wings Books: New York, 2000.

- Smith, P. David. Ouray Chief of the Utes Wayfinder Press: Ouray, Colorado, 1990.

- Wyss, Thelma Hatch. Bear Dancer the Story of a Ute Girl Margaret K. McElderry Books: New York, 2010.

- Bueler, Gladys R. Colorado's Colorful Characters Pruett Publishing Company: Boulder, Colorado, 1981.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chief Ouray. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- "Chief Ouray", Southern Ute

- "Chief Ouray", History to Go, Utah State Website

"Ouray". Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. 1900.

"Ouray". Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. 1900.- Find a Grave (burial site)

- "Ouray´s son... or not?", American-Tribes.com

- "Old Photos - Ute", American-Tribes.com