Chromoxylography

Chromoxylography was a colour woodblock printing process, popular from the mid-19th to the early-20th century, commonly used to produce illustrations in children's books, serial pulp magazines, and cover art for yellow-back and penny dreadfuls.[1] In the 19th century the art of relief engraving and chromoxylography was perfected by engravers and printers, most notably in England by Victorian engraver and printer Edmund Evans. A wide range of hues and tones were produced by the color mixing of the chromoxylography process—a technique that was complicated, requiring intricate engraving and printing for good results. Less expensive products, such as covers for pulp magazines, were coloured with as few colours as possible, often only two or three, whereas more intricate and expensive books and reproductions of paintings used as many as a dozen or more colors. For each colour a separate woodblock had to be carved.

Background

Full-colour printing in the 19th century relied on the relief process and colour wood engraving. Bamber Gascoigne explains that the "vast majority of colour wood engravings are reproductive work of the second half of the nineteenth century, at which time they were often referred to as chromoxylographs—meaning colour from wood, just as chromolithograph means colour from stone."[2] Relief prints were made by printing with engraved and coloured wood blocks.[3] In the 1830s, George Baxter repopularized colour relief printing, then called chromoxylography, using a "background detail plate printed in aquatint intaglio, followed by colours printed in oil inks from relief plates—usually wood blocks".[4]

Chromoxylography became a popular technique in the production of inexpensive books, such as children's toy books and serialized stories into the early-20th century.[5] The process was used simplistically in the mid-19th century to produce covers and illustrations for dime novels, penny dreadfuls, and children's books that were usually rendered, often ineffectively, only in primary colours, using one colour per wood block.[6] The process became much more elaborate with Edmund Evans work, London's premier engraver and printer of children's books, as he perfected the process, often using as many as ten colour blocks, mixing and combining primary colours to create a broad palette of colours and hues.[3][4]

Methods and uses

To make a relief print, the printer began with a wood block, engraved the image on the block by carving out areas that were not to be printed (or inked).[7] A wood block was carved for each primary colours, with the coloured ink coating the areas left in relief.[5] Gascoigne explains that the process required a "master craftsman [to sit] with an original painting in front of him and work out which areas of the image should be printed in which of the available colours to achieve the desired effect."[8] The printer engraved the image to the finer end grain of the woodblock.[9] For more complicated work the carver worked on the end grain of the wood, and with the use of fine hatchings to the wood that were inked separately achieved the look of blended colours. For the children's book market, which had lower profit margins, the printer would use fewer ink colours, which could be optimised by mixing colours such as blue and yellow to create green.[10]

The blocks were skillfully carved with extremely fine lines to create stippling and variations in tone.[7] Areas intended to be printed in a solid colour were marked, and then hatching lines of various thickness were carved into the wood so that colours could be overprinted, creating a variety of hues and tones. To create a blend of colours, blocks were hatched horizontally and diagonally to allow applications of multiple colours that resulted in browns, greens and greys.[11] Gascoigne explains that a "blockmaker would know whether to engrave thin white lines (for an almost solid tone), medium white lines (a mid-tone) or crosshatchings (leaving larger or smaller lozenges of colour to achieve sometimes little more than a faint tint when seen at a normal viewing distance)." Overlapping diagonal lines were carved to create dot-like shapes on the surface that took less ink and resulted in paler tones.[7]

Thicker hatchings were less expensive and easier to produce, but the result was not as attractive. Books that were to be produced as inexpensively as possible showed less engraving work and colour separation.[3] The chief problem was to maintain correct register so that the design on the block matched the design on the paper. To achieve a precise register small holes were drilled along each block, and the paper was pinned to it. When done correctly, the block's colour registers matched printed paper, although sometimes ink squash is visible along the edges of an illustration.[12] An electroplate was produced for each engraved wood block, inked according to the block, thereby tinting the paper in specified areas. The colour was applied as a solid, or in stripes of various of thickness, allowing for changes in hue.[3]

According to Gascoigne, 19th century chromoxylographs are identified by embossing on the back of the paper, distinctly delineated outlines, created by pressing the paper against the engraved blocks, and the presence of crosshatchings. He writes that "an impossibly and perfect and delicate area of crosshatching will suggest at first that the graver could not possibly have scooped out such small and regular interstices, but on closer inspection the lines in the two directions will be found to be of slightly different colours."[13]

Because the process was inexpensive, and commonly used to illustrate covers of inexpensive books such as mysteries and romances ("yellow backs" or "dime store novels") or magazines, and in rare instances, newspaper covers, complicated colour combinations generally were not necessary. Most often the printer only used primary colors and black.[3] The inexpensive technique of chromoxylography allowed publishers and printers to design covers as an attraction to purchase the book.[14]

The process was also used to produce higher quality children's books and toy books. Evans considered full colour printing a technique well-suited to the simple illustrations in children's books.[15] Evans reacted against crudely coloured children's book illustrations, which he believed could be beautiful and inexpensive if the print run was large enough to maintain the costs. In doing so, Evans collaborated with Walter Crane, Kate Greenaway and Randolph Caldecott.[16] Books illustrated by Kate Greenaway, Walter Crane and Randolph Caldecott, engraved and printed by Evans, became popular and remain as classic examples of illustrations for children's literature.[15]

Chromoxylography was additionally used to illustrate natural history books and to reproduce paintings. To achieve realistic reproductions an engraver often used 12 or more colour blocks.[17]

Gallery

Examples of chromoxylography

-

Cover art of Edward Vile's penny dreadful Black Bess or the Knight of the Road showing few hatchings to create variations in hue and tone.

-

1896 children's magazine cover showing thicker hatchings. The colour register slipped causing the print to blur.

-

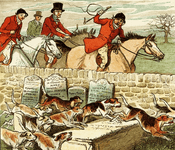

A subtle blend of colours is achieved using few colour blocks in this Randolph Caldecott image, printed by Edmund Evans.

-

Yellow is used to achieve a variety of hues, and fine hatchings allow for overprinting, as in this illustration by Walter Crane; printed by Edmund Evans in 1878.

Detail of a chromoxylograph

-

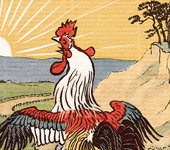

Image from Randolph Caldecott's "The House that Jack Built"

-

Close-up showing crosshatchings, mixed colours in the meadow, a pale hued sea, delineated sunrays, slight colour squash, and solid colours on the rooster.

References

- ↑ Ray, p. 64

- ↑ Gascoigne, section 23. a

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Penny Novels and Penny Dreadfuls". Stanford University Library. Retrieved 2010-05-30.

- 1 2 Pankow, p. 22

- 1 2 Fraser and Banks, p. 59

- ↑ University of Stanford

- 1 2 3 Gasgoigne, section 53.f

- ↑ Gascoigne, section 23.b.

- ↑ Gascoigne, section 23.b

- ↑ Gascoigne, section 53.f

- ↑ Gascoigne, section 23.c

- ↑ Gascoigne, section 68

- ↑ Gascoigne, section 55.s

- ↑ "Aspects of the Victoria Book:Penny Dreadfuls". British Library. Retrieved October 11, 2010

- 1 2 "Color Printing in the Nineteenth Century". University of Delaware Library. Retrieved 2010-02-28.

- ↑ "Randolph Caldecott Papers". de Grummond Collection. University of Southern Mississippi. Retrieved 2010-02-28.

- ↑ Gascoigne, section 23.d

Sources

- Fraser, Tom and Adam Banks. Designer's Color Manual: The Complete Guide to Color Theory and Application. (2004). Chronicle Books. ISBN 978-0-8118-4210-5

- Hardie, Martin. English Coloured Books. (1906). New York: Putnam

- Gascoigne, Bamber. How to Identify Prints. (1986) New York: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-23454-X

- McNair, John R. "Chromolithography and Color Woodblock: Handmaidens to Nineteenth Century Children's Literature. Children's Literature Association Quarterly. Volume 11, Number 4, Winter 1986-1987, pp. 193–197

- Pankow, David. Tempting the palette: a survey of colour printing processes (2005). Rochester NY:Rochester Institute of Technology. ISBN 1-933360-00-3

- Ray, Gordon Norton. The Illustrator and the book in England from 1790 to 1914. (1991) New York: Dover. ISBN 0-486-26955-8

Further reading

- Lundin, Anne. Literature and the child: romantic continuations, postmodern contestations. (1996) Iowa City: Iowa University Press. ISBN 0-87745-690-9