First Ivorian Civil War

| First Ivorian Civil War | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Armed insurgents in a technical. | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Belligerents | ||||||||

|

Supported by: | New Forces |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | ||||||||

|

YPA militia: Charles Blé Goudé | Guillaume Soro |

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | ||||||||

|

200+ government soldiers 100+ militias 1,200+ civilians | 300+ rebels |

15 French soldiers 1 UN peacekeeper | ||||||

| French military / UN peacekeepers |

FANCI (Government troops) / New Forces (FN) rebels / Young Patriots of Abidjan militia | |

|---|---|---|

| Dead | 13 French Army soldiers, 2 aid workers, 1 UN observer, 1 UN peacekeeper |

(Estimated) 200+ FANCI Government troops, 400+ rebels/militia, 1,200+ civilians |

| Wounded | 55 | 1,500+ |

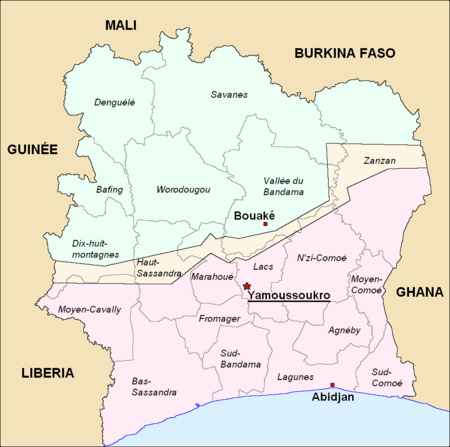

The First Ivorian Civil War was a conflict in the Ivory Coast (also known as Côte d'Ivoire) that began in 2002. Although most of the fighting ended by late 2004, the country remained split in two, with a rebel-held Muslim north and a government-held Christian south. Hostility increased and raids on foreign troops and civilians rose. As of 2006, the region was tense, and many said the UN and the French military failed to calm the civil war.

The Côte d'Ivoire national football team was credited with helping to secure a temporary truce when it qualified for the 2006 FIFA World Cup and brought warring parties together.[3]

The United Nations Operation in Côte d'Ivoire began after the civil war calmed, but peacekeepers have faced a complicated situation and are outnumbered by civilians and rebels. A peace agreement to end the conflict was signed on 4 March 2007.[4]

The Ivorian elections took place in October 2010 after being delayed six times. Fighting resumed on 24 February 2011 over the impasse on the election results, with the New Force rebels capturing Zouan-Hounien, and clashes in Abobo, Yamoussoukro and around Anyama[5][6]

Context of the conflict

The civil war revolves around a number of issues.

First, the end of the 33-year presidency of Félix Houphouët-Boigny forced the nation to grapple with the democratic process for the first time. Houphouët-Boigny had been president since the country's independence, and so the nation's political system was bound tightly to his personal charisma, and political and economic competence. The political system was forced to deal with open, competitive elections without Houphouët-Boigny from 1993 onward.

Then, the large number of foreigners in Côte d'Ivoire, and Ivorians of somewhat recent foreign descent, created an important issue of voting rights. Twenty-six percent of the population was of foreign origin, particularly from Burkina Faso, a poorer country to the north. Many of these had been Ivorian citizens for two generations or more, and some of them, of Mandinka heritage, can be considered native to the northern part of what is now known as Côte d'Ivoire. These ethnic tensions had been suppressed under the strong leadership of Houphouët-Boigny, but surfaced after his death. The term Ivoirity, originally coined by Henri Konan Bédié to denote the common cultural identity of all those living in Côte d'Ivoire came to be used by nationalist and xenophobic politics and press to represent solely the population of the southeastern portion of the country, particularly Abidjan.

Discrimination toward people of Burkinabé origin also made neighbor countries, particularly Burkina Faso, fear a massive migration of refugees.

An economic downturn due to a deterioration of the terms of trade between Third World and developed countries worsened conditions, exacerbating the underlying cultural and political issues.

Finally, unemployment forced a part of the urban population to return to the fields, which they discovered had been exploited.

Rising tensions

Violence was turned initially against African foreigners. The prosperity of Côte d'Ivoire had attracted many Africans from West Africa, and by 1998 they constituted 26% of the population, 56% of whom were Burkinabés.

In this atmosphere of increasing racial tension, Houphouët-Boigny's policy of granting nationality to Burkinabés resident in Côte d'Ivoire was criticized as being solely to gain their political support.

In 1995, the tensions turned violent when Burkinabés were killed in plantations at Tabou, during ethnic riots.

Ethnic violence had already existed between owners of lands and their hosts particularly in the west side of the country, between Bete and Baoule, Bete and Lobi. Since independence, people from the center of the country, Baoules, have been encouraged to move to fertile lands of the west and south-west of the country where they have been granted superficialities to grow cocoa, coffee and comestibles. Years later, some Bete have come to resent these successful farmers. Voting became difficult for these immigrants as they were refused voting rights.

Catalyst to the conflict

The catalyst for the conflict was the law quickly drafted by the government and approved in a referendum immediately before the elections of 2000 which required both parents of a presidential candidate to be born within Côte d'Ivoire. This excluded the northern presidential candidate Alassane Ouattara from the race. Ouattara represented the predominantly Muslim north, particularly the poor immigrant workers from Mali and Burkina Faso working on coffee and cocoa plantations.

Beginning of the civil war (2002)

Troops, many of whom originated from the north of the country, mutinied in the early hours of 19 September 2002. They launched attacks in many cities, including Abidjan. By midday they had control of the north of the country. Their principal claim relates to the definition of who is a citizen of Ivory Coast (and so who can stand for election as President), voting rights and their representation in government in Abidjan.

On the first night of the uprising, former president Robert Guéi was killed. There is some dispute as to what actually happened that night. The government said he had died leading a coup attempt, and state television showed pictures of his body in the street. However, it was widely claimed that his body had been moved after his death and that he had actually been murdered at his home along with fifteen other people. Alassane Ouattara took refuge in the French embassy, and his home was burned down.[7]

Attacks were launched almost simultaneously in most major cities; the government forces maintained control of Abidjan and the south, but the new rebel forces had taken the north and based themselves in Bouake.

Laurent Gbagbo considered deserters from the army, supported by interference from Burkina Faso, as the cause of destabilization.

France wished reconciliation, when the Côte d'Ivoire government wanted military repression. Eventually France sent 2500 soldiers to man a peace line and requested help from the UN.

Forces involved in the conflict include:

- Official government forces, the National Army (FANCI), also called loyalists, formed and equipped essentially since 2003

- The Young Patriots: nationalist groups aligned with President Laurent Gbagbo

- Mercenaries recruited by president Gbagbo:

- Belarusians pilots[8]

- Former combatants of Liberia, including under-17 youths, forming the so-called "Lima militia"[9]

- New Forces (Forces Nouvelles, FN), ex-northern rebels, who held 60% of the country

- French military forces: troops sent within the framework of Operation Unicorn and under UN mandate (UNOCI), 3000 men in February 2003 and 4600 in November 2004;

- Soldiers of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), White helmets, also under the UN.

The rebels were immediately well armed, not least because to begin with most were serving soldiers; it has been claimed they were also given support by Burkina Faso. Additionally, government supporters claimed the rebels were supported by France; however, rebels also denounced France as supporting the government, and French forces quickly moved between the two sides to stop the rebels from mounting new attacks on the south.

It was later claimed that the rebellion was planned in Burkina Faso by soldiers of the Ivory Coast close to General Guéï. Guillaume Soro, leader of the Patriotic Movement of Côte d'Ivoire (MPCI) later to be known as the Forces Nouvelles de Côte d'Ivoire/New Forces – the rebel movement – comes from a student union close to the FPI of Gbagbo, but was also a substitute for an RDR candidate in the legislative elections of 2000. Louis Dacoury Tabley was also one of the leaders of the FPI.

Once they had regrouped in Bouake, the rebels quickly threatened to move southwards to attack Abidjan again. France deployed the troops it had based in Ivory Coast, on 22 September, and blocked the rebels' path. The French said they had acted to protect their nationals and other foreigners, and they went into the northern cities to bring out expatriates from many nations. The USA gave (limited) support.

On 17 October, a cease-fire was signed, and negotiations started.

On 28 November, the popular Movement of the Ivory Coast of the Great West (MPIGO) and the Movement for Justice and Peace (MJP), two new rebel movements, took the control of the towns of Man and Danané, both located in the west of the country. France conducted negotiations. French troops dispatched to evacuate foreigners battled rebels near Man on 30 November. The clashes left at least ten rebels dead and one French soldier injured.[10]

The cease-fire nearly collapsed on 6 January when two groups of rebels attacked French positions near the town of Duékoué, injuring nine soldiers, one of them seriously. According to a French spokesman, French forces repelled the assault and counterattacked, killing 30 rebels.[11]

The Kléber (Marcoussis) agreements (2003–2004)

From 15 to 26 January 2003, the various parties met at Linas-Marcoussis in France to attempt to negotiate a return to peace. The parties signed a compromise deal on 26 January.[12] President Gbagbo was to retain power and opponents were invited into a government of reconciliation and obtained the Ministries for Defense and the Interior. Soldiers of the CEDEAO and 4000 French soldiers were placed between the two sides, forming a peace line. The parties agreed to work together on modifying national identity, eligibility for citizenship, and land tenure laws which many observers see as among the root causes of the conflict.

As of 4 February, anti-French demonstrations took place in Abidjan, in support for Laurent Gbagbo. The end of the civil war was proclaimed on 4 July. An attempt at a putsch, organized from France by Ibrahim Coulibaly, was thwarted on 25 August by the French secret service.

The UN authorized the formation of the UNOCI on 27 February 2004, in addition to the French forces and those of the CEDEAO.

On 4 March, the PDCI suspended its participation in the government, being in dissension with the FPI (President Gbagbo's party) on nominations to office within the administration and in public companies.

On 25 March, a peace march was organized to protest against the blocking of the Marcoussis agreements. Demonstrations had been prohibited by decree since 18 March, and the march was repressed by the armed forces: 37 died according to the government, between 300 and 500 according to Henri Konan Bédié's PDCI. This repression caused the withdrawal from the government of several opposition parties. A UN report of 3 May estimated at least 120 dead, and implicated highly placed government officials.[13]

The government of national reconciliation, initially composed of 44 members, was reduced to 15 after the dismissal of three ministers, among them Guillaume Soro, political head of the rebels, on 6 May.[14][15] That involved the suspension of the participation in the national government of the majority of political movements.

The French consequently were in an increasingly uncomfortable situation. The two sides each accused France of siding with the other: the loyalists because of its protection of the rebels, and the non-implementation the agreements of defense made with the Côte d'Ivoire; the rebels because it was preventing the capture of Abidjan. On 25 June, a French soldier was killed in his vehicle by a government soldier close to Yamoussoukro.

On 4 July 2003, the government and New Forces militaries signed an "End of the War" declaration, recognized President Gbagbo's authority, and vowed to work for the implementation of the LMA and a program of Demobilization, Disarmament and Reintegration (DDR).

In 2004, various challenges to the Linas-Marcoussis Accord occurred. Violent flare-ups and political deadlock in the spring and summer led to the Accra III talks in Ghana. Signed on 30 July 2004 the Accra III Agreement reaffirmed the goals of the LMA with specific deadlines and benchmarks for progress. Unfortunately, those deadlines – late September for legislative reform and 15 October for rebel disarmament – were not met by the parties. The ensuing political and military deadlock was not broken until 4 November 2004.

The resumption of fighting

The timetable outlined in the final version of the Linas-Marcoussis Accord was not respected. The bills envisaged in the process were blocked by the FPI, the Ivorian National Assembly. The conditions of eligibility for the presidential poll were not re-examined, because Laurent Gbagbo claimed the right to choose a prime minister, not in accordance with agreements suggested in Accra. Faced with political impasse, the disarmament whose beginning had been envisaged fifteen days after the constitutional modifications did not begin in end-October.

A sustained assault on the press followed, with newspapers partial to the north being banned and two presses destroyed. Dissenting radio stations were silenced.

UN soldiers opened fire on hostile demonstrators taking issue with the disarmament of the rebels on 11 October. The rebels, who took the name of New Forces (FN), announced on 13 October their refusal to disarm, citing large weapons purchases by the Côte d'Ivoire national army (FANCI). They intercepted two trucks of the FANCI full of heavy weapons travelling towards the demarcation line. On 28 October, they declared an emergency in the north of the country.

Ivorian-French violence

On 4 November, Ivorian President Laurent Gbagbo ordered air strikes against rebels, and Ivorian aircraft began a bombardment of Bouaké. On 6 November, at least one Ivorian Sukhoi Su-25 bombed a French base in Bouaké, supposedly by accident, killing nine French soldiers and an American aid worker and injuring 31 others.

French forces conducted an overland attack on Yamassoukro Airport, destroying two Su-25s and three attack helicopters, and two airborne military helicopters were shot down over Abidjan. One hour after the attack on the camp, the French Army established control of Abidjan Airport. France flew in reinforcements and put three jets in Gabon on standby.

Simultaneously, the Young Patriots of Abidjan rallied by the State media, plundered possessions of French nationals. Several hundred Westerners, mainly French, took refuge on the roofs of their buildings to escape the mob, and were then evacuated by French Army helicopters. France sent in reinforcements of 600 men based in Gabon and France while foreign civilians were evacuated from Abidjan airport on French and Spanish military airplanes. A disputed number of rioters were killed after French troops opened fire.

Laurent Gbagbo

Laurent Gbagbo founded the FPI (main opposition party) to restore modernization in the country again, by building infrastructure, transport, communication, water and clean energy.[16]

Ending of the conflict (2005–2007)

By 8 November 2004, most expatriate Westerners (French mainly, but also Moroccan, German, Spanish, British, Dutch, Swiss, Canadian, and American) in Côte d'Ivoire had chosen to leave. On 13 November, President of the Ivorian National Assembly Mamadou Coulibaly (FPI) declared that the government of the Ivory Coast did not take any responsibility in the bombardment of 6 November, and announced its intention of approaching the International Court of Justice:

- for the destruction of the Ivory Coast Air force, only recently re-equipped;

- for activities by the French Army responsible for several deaths.

In an interview with The Washington Post, Laurent Gbagbo called into question even the French deaths. Lastly, on the morning of 13 November 2006 expatriate French had returned to France, and 1600 other European expatriates had left.

The United Nations Security Council passed Resolution 1572 (2004) on 15 November, enforcing an arms embargo on the parties.

A meeting of the Ivorian political leaders, moderated by South African President Thabo Mbeki was held in Pretoria from 3 to 6 April 2005. The resulting Pretoria Agreement declared the immediate and final cessation of all hostilities and the end of the war throughout the national territory.[17] Rebel forces started to withdraw heavy weapons from the front line on 21 April.[18]

Presidential elections were due to be held on 30 October 2005, but in September the UN Secretary General, Kofi Annan, announced that the planned elections could not be held in time.[19] On 11 October 2005, an alliance of Côte d'Ivoire's main opposition parties called on the UN to reject African Union proposals to keep President Laurent Gbagbo in office for up to an additional 12 months beyond the end of his mandate.[20] The Security Council approved this a few days later.[21]

The Côte d'Ivoire national football team helped secure a truce in 2006 when it qualified for the World Cup and convinced Gbagbo to restart peace talks.[3] It also helped further reduce tensions between government and rebel forces in 2007 by playing a match in the rebel capital of Bouaké, an occasion that brought both armies together peacefully for the first time.[22] In late 2006, the elections were again delayed, this time until October 2007.

On 4 March 2007, a peace agreement was signed between the government and the New Forces in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. New Forces leader Guillaume Soro was subsequently appointed prime minister and took office in early April.[23] On 16 April, in the presence of Gbagbo and Soro, the UN buffer zone between the two sides began to be dismantled, and government and New Forces soldiers paraded together for the first time. Gbagbo declared that the war was over.[24]

On 19 May, the disarmament of pro-government militia began as the Resistance Forces of the Great West gave up over a thousand weapons in a ceremony in Guiglo, at which Gbagbo was present.[25]

Central government administration began returning to the New Forces-held areas in June, with the first new prefect in the north being installed on 18 June in Bouaké.[26] ddd

On 29 June, rockets were fired at Soro's plane at the airport in Bouaké, significantly damaging the plane. Soro was unhurt, although four others were said to have been killed and ten were said to have been wounded.[27]

Gbagbo visited the north for the first time since the outbreak of the war for a disarmament ceremony, the "peace flame", on 30 July; Soro was also present. This ceremony involved burning weapons to symbolize the end of the conflict.[28][29] It was previously planned for 30 June and then for 5 July, but was delayed.[30] At the ceremony, Gbagbo declared the war over and said that the country should move quickly to elections, which were planned for 2008.[29]

On 27 November 2007, Gbagbo and Soro signed another agreement in Ouagadougou, this one to hold the planned election before the end of June 2008. On 28 November, Gbagbo flew to Korhogo, then to Soro's native Ferkessedougou, at the start of a three-day visit to the far north, the first time he had been to that part of the country since the outbreak of the war, marking another step toward reconciliation.[31]

On 22 December, a disarmament process planned to take place over the course of three months began with government soldiers and former rebels withdrawing from their positions near what had been the buffer zone; the forces of the two sides respectively went to barracks in Yamoussoukro and Bouaké. Gbagbo and Soro were present at Tiébissou to mark the event; Gbagbo said that, as a result, the front lines of the conflict no longer existed, and Soro said that it "effectively, concretely marks the beginning of disarmament".[32]

UN Peacekeeping Forces

As of 18 May 2005 the UN forces, as result of the continued flaring up of ethnic as well as rebel-government conflict, have experienced difficulty maintaining peace in the supposedly neutral "confidence zone", particularly in the west of the country. UN troops have been deployed laterally, forming a belt across the middle of Côte d'Ivoire stretching across the whole country and roughly dividing it in two from north to south.

This area has a mixture of ethnic groups, notably the Dioula who are predominantly Muslim and typically aligned with the New Forces, who typically sway to both government and rebel loyalties. This conflict of interests has created widespread looting, pillaging and various other human rights abuses amongst groups based on the typical political alignment of their ethnicity.

A total of 25 UN personnel have died during UNOCI.

In 2005, over 1,000 protesters invaded a UN base in Guiglo and took control but were forced back by armed UN peacekeepers. A total of 100 protesters died and left 1 UN peacekeeper dead and another wounded.

This is not to say that there are no regions where ethnic groups co-exist peacefully, however, the UN troops lack the man-power to prevent inter-ethnic violence.

On 21 July 2007 the UNOCI suspended a Moroccan peacekeeping unit in Ivory Coast following an investigation into allegations of widespread sexual abuse committed by UN peacekeepers in the nation.

Post-election dispute

The 2010–2011 post-election dispute between former president Laurent Gbagbo and Alassane Ouattara, which left 3,000 people dead. In 2012 a national independent commission set up to investigate 2011 atrocities of 2011 hostilities, during the 2011 post-elections. They found that pro-Gbagbo forces were responsible for the death of 1,400 people, while forces fighting for Ouattara killed 700 people.

Resurgence of violence after the presidential elections

The presidential elections that should have been organized in 2005 were postponed until October 2010. The preliminary results announced by the Electoral Commission showed a loss for Gbagbo in favor of his rival, former prime minister Alassane Ouattara. The ruling FPI contested the results before the Constitutional Council, charging massive fraud in the northern departments controlled by the rebels of the Forces Nouvelles de Côte d'Ivoire (FNCI). These charges were contradicted by international observers.

The report of the results led to severe tension and violent incidents. The Constitutional Council, which consists of Gbagbo supporters, declared the results of seven northern departments unlawful and that Gbagbo had won the elections with 51% of the vote (instead of Ouattara winning with 54%, as reported by the Electoral Commission). After the inauguration of Gbagbo, Ouattara, recognized as the winner by most countries and the United Nations, organized an alternative inauguration. These events raised fears of a resurgence of the civil war. The African Union sent Thabo Mbeki, former President of South Africa, to mediate the conflict. The UN Security Council adopted a common resolution recognising Alassane Ouattara as winner of the elections, based on the position of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS).

ECOWAS suspended Côte d'Ivoire from all its decision-making bodies[33] while the African Union also suspended the country's membership.[34] On 16 December an appeal from Ouattara to his supporters to march to Abidjan, the economic capital of the country, and seize some government buildings, led to severe clashes leaving many casualties. In Tiébissou, there were reports of fighting between rebel forces and the Ivorian army.[35]

Clashes between Laurent Gbagbo's and the New Force rebels occurred in the western town of Teapleu on 24 February 2011.[36] Clashes were reported in Abidjan, Yamoussoukro and around Anyama by 25 February[5] with the town of Zouan-Hounien being captured from government forces in a morning attack on 25 February.[6] By the end of March, Northern forces had taken Bondoukou and Abengourou in the east, Daloa, Duekoue, and Gagnoa in the west, the main western port of San Pédro, and the capital Yamoussoukro, for control of three quarters of the country. Southern forces supposedly loyal to Gbagbo have so far not been willing to fight, and Northern forces have won every battle they have fought.[37]

UN Security Council Resolution 1975

The United Nations Security Council Resolution 1975 imposed international sanctions on the territory run by Laurent Gbagbo's regime.

See also

- 2004 French–Ivorian clashes

- 2010–2011 Ivorian crisis

- Second Ivorian Civil War (March and April 2011)

References

- ↑ "Cote d'Ivoire, since 2002". Acig.org. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

- ↑ "Cote d'Ivoire, since 2002". Acig.com. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

- 1 2 Stormer, Neil (20 June 2006). "More than a game". Common Ground News Service. Retrieved 2 March 2010.

- ↑ "Côte d'Ivoire: Can the Ouagadougou Agreement Bring Peace?". International Crisis Group. 27 June 2007. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- 1 2 "Cote d'Ivoire: Urban Exodus as Violence Escalates". Allafrica.com. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

- 1 2 "Ivory Coast: Rebels take western town Zouan-Hounien". BBC News. 25 February 2011.

- ↑ Asante, Molefi Kete (2014). The History of Africa: The Quest for Eternal Harmony. New York and London: Routledge. p. 324. ISBN 9781135013493.

- ↑ Mladenov, Alexander (2015). Su-25 'Frogfoot' Units In Combat. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781472805690.

- ↑ Archived 14 July 2005 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Côte d'Ivoire: Chaotic Conflict Deepens As Government Troops Fight To Recover Lost Territory In Ivory Coast (Page 1 of 2)". AllAfrica.com. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

- ↑ "'Blue helmets' plan for Ivory Coast". BBC News. 7 January 2003.

- ↑ "Linas-Marcoussis Agreement: Cote d'Ivoire". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

- ↑ "Report of the Commission of Inquiry: On the events connected with the march planned for 25 March 2004 in Abidjan". Security Council. 29 April 2004.

According to statistics gathered by the Commission of Inquiry on the basis of official and other documents received, and provided in the annex, at least 120 people were killed, 274 wounded and 20 disappeared

- ↑ "Gbagbo sacks rebel chief from power-sharing cabinet", IRIN, May 20, 2004.

- ↑ "Ivorian rebel ministers sacked", BBC News, May 20, 2004.

- ↑ Kobo, Kingsley. "Ivory Coast struggles with reconciliation". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- ↑ "ReliefWeb" (PDF). ReliefWeb. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

- ↑ "United Nations News Centre". UN News Service Section. 21 April 2005. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

- ↑ "UN rules out Ivory Coast election", BBC News, 8 September 2005.

- ↑ "Opposition alliance calls on UN to reject 12 more months of Gbagbo", IRIN, 11 October 2005.

- ↑ "UN endorses plan to leave president in office beyond mandate", IRIN, 14 October 2005.

- ↑ Merrill, Austin (10 July 2007). "Best Feet Forward". Vanity Fair. Retrieved 2 March 2010.

- ↑ "Former rebel leader takes over as Ivory Coast's prime minister", Associated Press (International Herald Tribune), 4 April 2007.

- ↑ "Ivory Coast's Gbagbo says the war is over", Reuters (IOL), 17 April 2007.

- ↑ "Laurent Gbagbo lance le désarmement des milices dans l'ouest ivoirien", AFP (Jeuneafrique.com), 19 May 2007 (French).

- ↑ "Côte d'Ivoire: Soro installe le premier préfet en zone rebelle", AFP (Jeuneafrique.com), 18 June 2007 (French).

- ↑ "Côte d'Ivoire: arrestations après l'attentat contre le Premier ministre Soro", AFP (Jeuneafrique.com), 30 June 2007 (French).

- ↑ "Ivory Coast leaders burn weapons", BBC News, 30 July 2007.

- 1 2 "Côte d'Ivoire: Gbagbo en zone rebelle pour prôner la paix et des élections rapides", AFP (Jeuneafrique.com), 30 July 2007 (French).

- ↑ "Ivory Coast president to visit rebel zone", AFP (IOL), 12 July 2007.

- ↑ "Gbagbo calls for peace before polls", Sapa-AFP (IOL), 29 November 2007.

- ↑ "Ivory Coast factions withdraw from former buffer zone, begin disarmament process", Associated Press (International Herald Tribune), 22 December 2007.

- ↑ "FINAL COMMUNIQUE ON THE EXTRAORDINARY SESSION OF THE AUTHORITY OF HEADS OF STATE AND GOVERNMENT ON COTE D’IVOIRE ", ECOWAS, 7 December 2010.

- ↑ "COMMUNIQUE OF THE 252ND MEETING OF THE PEACE AND SECURITY COUNCIL ", African Union, 9 December 2010.

- ↑ "Two rebel soldiers killed in Ivory Coast", Africanews, 16 December 2010.

- ↑ "Ivory Coast: army and ex-rebels 'breach ceasefire'". BBC News. 24 February 2011.

- ↑ Nossiter, Adam (30 March 2011). "Ivory Coast Rebels Seize Yamoussoukro". The New York Times.

- Safer Access - A Synopsis of Armed Groups and Political Parties in Cote d’Ivoire

- (German) Sow, Adama: Ethnozentrismus als Katalysator bestehender Konflikte in Afrika südlich der Sahara, am Beispiel der Unruhen in Côte d`Ivoire at: European University Center for Peace Studies (EPU), Stadtschleining 2005

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ivorian Civil War. |