Clarence Railway

.jpg)

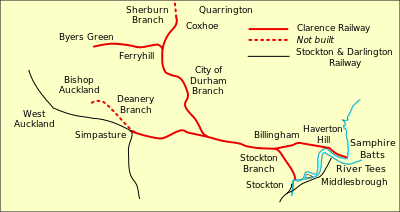

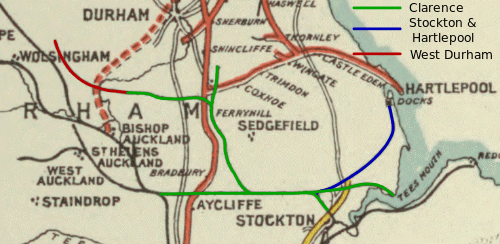

The Clarence Railway was an early railway company that operated in north-east England between 1833 and 1853. The railway was built to take coal from mines in County Durham to ports on the River Tees and was a competitor to the Stockton and Darlington Railway (S&DR). It suffered financial difficulty soon after it opened because traffic was low and the S&DR charged a high rate for transporting coal to the Clarence, and the company was managed by the Exchequer Loan Commissioners after July 1834. An extension of the Byers Green branch was opened in 1839 by the independent West Durham Railway to serve collieries in Weardale.

The Stockton and Hartlepool Railway opened in 1841 to connect the Clarence to Hartlepool Docks and the Hartlepool West Harbour & Dock opened in West Hartlepool in 1844. On 17 May 1853 the Clarence Railway, Hartlepool West Harbour & Dock and Stockton and Hartlepool Railway were merged to become the West Hartlepool Harbour and Railway. The West Hartlepool Harbour and Railway became part of the North Eastern Railway in 1865.

History

Origins

The S&DR opened in 1825 linking Stockton-on-Tees with the coal fields in the Shildon area via Darlington,[1] although a more direct, northerly route to Stockton had support in that town.[2] The promoters of a competing Tees and Weardale Railway, supported by Christopher Tennant, petitioned Parliament in 1823 for permission for a railway from the coal field south of Durham to the River Tees to allow onward transport by sea.[3] This application failed as the standing orders had not been complied with,[4] and another in 1824 failed, partly due to opposition to use of steam locomotives.[5] By 1826 the S&DR had outgrown the port in Stockton and initially a port was proposed on the north bank of the Tees near Haverton Hill, but a branch to Middlesbrough on the south bank was proposed at a meeting in July 1827, and this was ratified by the shareholders that October.[6]

The Tees & Weardale promoters developed a new scheme to transport coal to Haverton Hill: a main line that formed a junction the S&DR at Simpasture, a branch to the Deanery estate and a branch to Stockton that would provide a shorter route than the S&DR. This route didn't go into Weardale, so it was named Clarence Railway after the Duke of Clarence, later King William IV.[7] The line was surveyed by Tennant with Edward Steel, an early assistant of Stephenson, the railway was supported by a town meeting in Stockton, and Henry Blanshard leased Coxhoe colliery for a high price from the Hale sisters, on condition they use their family's influence to promote the railway.[8]

The Clarence Railway Act received Royal Assent on 23 May 1828,[9] for a 26-mile-73-chain (43.3 km) line from Haverton Hill to Simpasture with three branches, one to the Deanery estate near Bishop Auckland, another to Broom Hill, 2 miles (3.2 km) north of Ferryhill and a third to Stockton.[10] The route was surveyed again, this time by George Leather, who suggested different route that was straighter and with better gradients. Samphire Batts replaced Haverton Hill as the terminus, as this would allow loaded ships in the docks at low water. Branches were planned to Sherburn via Coxhoe, Durham via Shincliffe, Byers Green and to the S&DR at West Auckland,[11] although this last branch was not in the bill put before Parliament.[12] Opposed by the S&DR and also the Marquis of Londonderry, who was building a port at Seaham and planning a railway to West Rainham, the second Clarence Railway Act received royal assent on 1 June 1829. The new railway was 45 miles 23 chains (72.9 km) long; the main line to Samphire Batts was now 15 miles (24 km) long, the City of Durham branch was 13 miles (21 km), and there were four other branches to Stockton, Deanery, Sherburn and Byers Green.[13] Due to the objection of Robert Surtees of Mainsforth, locomotives were not permitted on parts of the Byers Green and City of Durham branches.[14]

Opening and early operation

Further Acts in 1832 and 1833 allowed for two more branches and the Durham branch to be cut short at Shincliffe.[9] Construction involved heavy earthworks, such a 67-foot (20 m) deep cutting through solid rock near Ferryhill and a 75-foot (23 m) high embankment at Whitton or Bishopton Beck. With the main line built between Simpasture and Samphire Batts, the Stockton branch complete, the Durham branch ready as far as Thrislington and the Sherburn branch as far as Quarrington, the company needed to earn some income. It started carrying coal on its main line in August 1833, and in a year had reduced the traffic over the S&DR to Stockton from over 26,000 tons to under 9,500 tons.[15] In October 1833, the Clarence started shipping coal for export, but the S&DR continued to charge the landsale rate, rather than the lower export rate.[16]

.jpg)

In January 1834 the railway opened as far as Quarrington on the Sherburn branch and a straith was opened at Haverton Hill; Port Clarence opened at Samphire Batts a few months later. Traffic was low and in financial difficultly the company asked the Exchequer Loan Commissioners to take over management in July, and the line was managed from London.[17] A branch to Chilton Pit was authorised in 1833 and opened in 1835 and the Byers Green branch opened on 31 March 1837; the City of Durham branch was not built north of Ferryhill, and nor was the Deanery branch.[18][19] The line was mainly double track, originally laid with 38 pounds per yard (19 kg/m) rails, but later heavier ones weighing 44–45 lb/yd (22–22 kg/m) were used; trains run on the right.[20] Horses were used exclusively until 1835, when a colliery owner began trains using his locomotives after having obtained permission from Surtees; the Clarence Railway used them from the following year.[21] A passenger service was operated over the Clarence Railway between Stockton and Coxhoe from January 1836, initially by a contractor using horse-drawn coaches. A service using steam locomotives hauling two carriages began in June 1838, a new contractor providing the carriages and two locomotives, Victoria and Norton. The three services a day ran the 16 1⁄4 miles (26.2 km) at an average speed of 18 miles per hour (29 km/h); the fare was 2s outside and 2s 6d inside; a horse omnibus provided a connecting service between Coxhoe and Durham. In 1839 the Clarence owned twelve locomotives for hauling mineral trains; these travelled at 8 miles per hour (13 km/h).[22][23]

West Durham Railway

Plans for a South Durham Railway, connecting the Clarence Railway's Byers Green branch with the collieries in Weardale, was presented to Parliament in 1836, but the bill failed in the House of Lords[24] and amended plans failed again the following year.[25] In March 1837 some wagons of coal were drawn by horse on temporary track laid on the Byers Green branch to allow the Clarence Railway to show the line had been opened within the limit of time specified in its Act; the branch was only fully open in 1841.[26] Work started on the West Durham Railway (WDR) in 1837, effectively an extension of the Byers Green branch to Willington Colliery; an Act for the line received Royal Assent on 4 July 1839. A 2 1⁄4 miles (3.6 km) section of line had opened on 12 June, although coal was not carried until 19 October, as before then locomotives were unable to be used on the Byers Green branch. From Byers Green a stationary engine was used to haul loaded wagon up a 5⁄8 mile (1.0 km) incline, the River Wear was crossed by a 206 feet (63 m) bridge and there were two more inclines before the terminus.[27][28] The line was primarily for minerals, although there was a Saturday market-day train to Stockton;[29] in 1854 this was still horse-drawn to Ferryhill, a dandy cart was used by the horse after it started the train at Byers Green.[30]

Stockton and Hartlepool Railway

Christopher Tennant, who had moved to Hartlepool, backed the Hartlepool Dock & Railway (HD&R) and this was given permission on 1 June 1832 for a line from the coal miles in central Durham to a port at Hartlepool. With a 14-mile (23 km) main line, 9 1⁄4 miles (14.9 km) of branch and 65 acres (26 ha) of land set aside for the docks,[31] trains ran between Thornley pit and Castle Eden after January 1835, Hartlepool dock opened that July and on 23 November the first train ran the 12 1⁄4 miles (19.7 km) between Haswell and Hartlepool. By the end of that year there was 14 1⁄2 miles (23.3 km) of line operational.[32]

In 1837 the Great North of England, Clarence & Hartlepool Junction Railway (GNEC&HJR) obtained permission for a line connecting the HD&R with the Byers Green branch, thus giving access to Hartlepool Dock bypassing Stockton. The Stockton and Hartlepool Railway was built to keep the traffic on the Clarence by building a branch from Billingham to Hartlepool.[25] Work started in 1839, without an Act of Parliament, and the line officially opened to passengers on 9 February 1841, although freight had travelled earlier.[lower-alpha 1] At Hartlepool an HD&R locomotive took trains forward to a 14 feet (4.3 m) inclined plane to a new Victoria Dock.[34] The S&HR was incorporated by an Act that received Royal Assent on 30 June 1842.[35]

The WDR closed for some weeks at the beginning of 1842 as it was short of money. This had an adverse effect on the revenues of the Clarence, the Exchequer Loan Commissioners taking possession of the railway that September, to sell it by public auction, although the debt was paid by raised by issuing and selling more shares.[36] The Stockton and Hartlepool Railway leased the Clarence Railway for 21 years from 2 September 1844, and the Clarence paid its first dividend, of 1 1⁄2 per cent, in 1845.[37][38]

To prevent traffic being diverted over the shorter GNEC&HJR to Hartlepool, the WDR was linked to the Clarence Railway by 97 yards (89 m) line over private land; as this was not limited by Act and the Clarence was able to change whatever toll it wished. The GNEC&HJR also found it lacked permission in its Act of 1837 to cross the Clarence to reach the Byers Green. Unable to come an agreement it returned to Parliament in 1843, where the GNEC&HJR was able to fix a toll for traffic on the short private line and gain permission to build a bridge over the line. However, the Clarence Railway still refused to co-operate building a bridge over the line and it was 1846 before the railway was completed.[39][38]

Hartlepool West Harbour & Dock

The Hartlepool West Harbour & Dock received permission on 23 May 1844,[40] and this opened on the Stranton shore on 1 June 1847.[41] Port Clarence suffered as traffic was being diverted to Hartlepool and the relationship between the S&HR and the Clarence Railway became strained. Some Clarence shareholders suggested a merger with the Stockton and Darlington Railway. Tennant had died in 1839;[42] Ralph Ward Jackson had backed the S&HR and Hartlepool West Harbour & Dock[43] and now negotiated a permanent lease of the Clarence from 1 January 1851. The Hartlepool West Harbour and Stockton and Hartlepool Railway were united from 1 July 1851.[44] By an Act given Royal Assent on 30 June 1852, the Clarence Railway, Hartlepool West Harbour & Dock and Stockton and Hartlepool Railway were merged to become the West Hartlepool Harbour and Railway on 17 May 1853;[45] Clarence Railway shareholders held the majority of the shares with voting rights.[46]

West Hartlepool Harbour and Railway

In 1852 the Leeds Northern Railway (LNR) reached Stockton and formed a junction with the Clarence Railway Stockton branch; an alliance had been formed and in anticipation the West Harbour had been enlarged from 13 to 44 acres (5.3 to 17.8 ha).[47] From the following year the West Hartlepool moved services to the LNR Stockton station and this became known as North Stockton, the 1848 S&DR station becoming South Stockton.[48] A price war broke out between the LNR and York, Newcastle and Berwick Railway (YN&BR), the fare for the 238 miles (383 km) between Leeds and Newcastle dropping to two shillings.[lower-alpha 2][50]

In 1862 the WHH&R was in financial difficulty, and as a result of legal action it was discovered that the company owned over £3,700,000, above the permitted £2,800,000; the level of debenture debt was almost three times that allowed. The company had purhased colleries and steam ships costing £1,000,000.[51] Jackson was held responsible, and he resigned in April, although a report the following year showed there had been good commercial reasons for buying the collieries and ships.[52] The debt was able to be converted into shares in 1863 and the new board sold the ships at a loss, but it was not possible to sell the coal mines, as the trade in coal being depressed at the time due to the American Civil War.[53] Jackson suggested merger of the WHH&R and NER in a letter to the Railway Times in April 1864, and this was agreed later that year. An Act was gained the following year[54] and the companies merged in June or July 1865. [lower-alpha 3]

Later history

The merger of the West Durham Railway with the NER was agreed in 1866 and was complete in 1870.[55] The NER opened a new line to Bishop Auckland in 1885 from the Byers Green branch and the passenger service was diverted over this line, a new station opening at Byers Green.[56] The West Durham Railway closed west of Todhills in 1891.[29] From 1913 former Clarence Railway lines were electrified with 1,500 Vdc overhead lines and electric locomotives hauled coal trains between Shildon and Erimus marshalling yard, which had opened in 1908 between Middlesbrough and Thornaby. The trains took the former S&DR line from Shildon to Simpasture Junction, joining the former Clarence Railway line to Carlton, where a later line allowed access to the Stockton to Middlesbrough extension. The locomotives operated for 20 years, but then coal traffic had reduced, which made it uneconomical to maintain the electrification system.[57]

As a result of the Railways Act 1921, on 1 January 1923 the North Eastern Railway became the North Eastern area of the London and North Eastern Railway (LNER).[58][59] In 1933 The rest of the former West Durham Railway was closed.[29] In 1939 the services from Spennymoor to Bishop Auckland were withdrawn and the Billingham to Port Clarence services cut back to Haverton Hill.[60]

During World War II a Royal Ordnance Factory was built at ROF Aycliffe, served by two stations at Simpasture and Demons Bridge.[61] Britain's railways were nationalised on 1 January 1948 and the lines were placed under the control of British Railways.[58] On 31 March 1952 the passenger service was withdrawn from Stockton to Spennymoor via Ferryhill. On 14 June 1954 the public passenger service ceased on the Port Clarence Branch, although workman's trains continued until November 1961. In 1963 the line closed between Simpasture and the junction with the former Durham branch.[62]

Legacy

.jpg)

Current Durham Coast Line passenger services provide one train per hour over the route of the former Clarence Railway from Stockton to Billingham, from where the former Stockton and Hartlepool Railway is taken to Hartlepool; four trains a day travelling between London Kings Cross and Sunderland use the route.[63] The line to Port Clarence is used by an irregular freight service, the branch signalled for one train working.[64] The freight only Stillington Branch follows the route of the former Clarence Railway Durham branch to Ferryhill south junction. As of 2012 this two track railway carries three freight services a day, but this could be increased if freight is diverted from the East Coast Main Line. It is planned to carry out any necessary infrastructure works to allow the diversion of Intercity Express Programme Class 800 and 801 units over the line by 2019.[65]

The Auckland Way Railway Path follows the route of the Byers Green branch from Spennymoor, taking the route of the later NER branch to Bishop Auckland at Byers Green.[66]

References and notes

Notes

- ↑ Hoole (1974, p. 146) states the line was open for freight on 12 December 1840, whereas Tomlinson (1915, pp. 344–346) mentions a train of coal travelled in January.

- ↑ Two shillings in 1852 was worth about the same as £9.80 today.[49]

- ↑ Tomlinson (1915, p. 619) gives the date as 1 July, Awdry (1990, p. 164) states 5 July, and the National Archive website entry for the West Hartlepool Harbour and Railway Company gives 30 June.

References

- ↑ Tomlinson 1915, pp. 105–107.

- ↑ Tomlinson 1915, p. 57.

- ↑ Tomlinson 1915, p. 87.

- ↑ Tomlinson 1915, p. 88.

- ↑ Tomlinson 1915, pp. 101–102.

- ↑ Tomlinson 1915, pp. 166–167.

- ↑ Tomlinson 1915, pp. 167–168.

- ↑ Tomlinson 1915, pp. 170–171.

- 1 2 Tomlinson 1915, p. 234.

- ↑ Tomlinson 1915, p. 175.

- ↑ Tomlinson 1915, pp. 177–178.

- ↑ Tomlinson 1915, p. 179.

- ↑ Tomlinson 1915, p. 180.

- ↑ Tomlinson 1915, pp. 178–181.

- ↑ Tomlinson 1915, p. 236.

- ↑ Tomlinson 1915, p. 237.

- ↑ Tomlinson 1915, p. 239.

- ↑ Cobb 2006, pp. 447–448, 460.

- ↑ Hoole 1974, p. 130.

- ↑ Whishaw 1842, pp. 59, 60–61.

- ↑ Tomlinson 1915, p. 386.

- ↑ Hoole 1974, pp. 130–131.

- ↑ Whishaw 1842, pp. 60–62.

- ↑ Tomlinson 1915, pp. 289–290.

- 1 2 Tomlinson 1915, pp. 297–298.

- ↑ Tomlinson 1915, p. 312.

- ↑ Tomlinson 1915, pp. 335–336.

- ↑ Hoole 1974, pp. 178–179.

- 1 2 3 Hoole 1974, p. 180.

- ↑ Tomlinson 1915, p. 529.

- ↑ Allen 1974, p. 74.

- ↑ Allen 1974, p. 75.

- ↑ "The National Heritage List for England (No.1250389)". English Heritage. Retrieved February 2014. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Tomlinson 1915, pp. 344–346.

- ↑ Hoole 1974, p. 146.

- ↑ Tomlinson 1915, pp. 475–476.

- ↑ Allen 1974, p. 102.

- 1 2 Tomlinson 1915, pp. 476–477.

- ↑ Allen 1974, pp. 67, 101–102.

- ↑ Tomlinson 1915, p. 477.

- ↑ Tomlinson 1915, p. 486.

- ↑ Heavsides, Henry. The Annals of Stockton-on-Tees. H. Heavsides & Son. p. 117.

- ↑ Waller, Philip (2004). "Jackson, Ralph Ward". The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/37591.

- ↑ Tomlinson 1915, pp. 509–510.

- ↑ Hoole 1974, pp. 147–148.

- ↑ "West Hartlepool Harbour and Railway Company". The Spectator. 11 July 1863. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ↑ Tomlinson 1915, pp. 512–514.

- ↑ Hoole 1974, p. 144.

- ↑ UK CPI inflation numbers based on data available from Gregory Clark (2016), "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)" MeasuringWorth.

- ↑ Tomlinson 1915, p. 515.

- ↑ Tomlinson 1915, pp. 599–600.

- ↑ Tomlinson 1915, p. 602.

- ↑ Tomlinson 1915, pp. 603, 610.

- ↑ Tomlinson 1915, p. 614.

- ↑ Tomlinson 1915, pp. 627, 644.

- ↑ Hoole 1974, p. 160.

- ↑ Allen 1974, pp. 204–205.

- 1 2 Hedges 1981, pp. 88, 113–114.

- ↑ Allen 1974, p. 234.

- ↑ Hoole 1974, pp. 132, 169.

- ↑ "Clarence Railway". Durham History. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- ↑ Hoole 1974, pp. 132, 144, 160.

- ↑ Network Rail 2012, pp. 124–125.

- ↑ Network Rail 2012, pp. 64–67.

- ↑ Network Rail 2012, pp. 91–93.

- ↑ "Auckland Way Railway Path" (PDF). Durham County Council. 2011. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

Sources

- Allen, Cecil J. (1974) [1964]. The North Eastern Railway. Ian Allan. ISBN 0-7110-0495-1.

- Awdry, Christopher (1990). Encyclopaedia of British Railway Companies. Patrick Stephens. ISBN 1-85260-049-7.

- Cobb, Colonel M.H. (2006). The Railways of Great Britain: A Historical Atlas. Ian Allan. ISBN 978-07110-3236-1.

- Hedges, Martin, ed. (1981). 150 years of British Railways. Hamyln. ISBN 0-600-37655-9.

- Hoole, K. (1974). A Regional History of the Railways of Great Britain: Volume IV The North East. David & Charles. ISBN 0715364391.

- Tomlinson, William Weaver (1915). The North Eastern Railway: Its rise and development. Andrew Reid and Company. OCLC 504251788.

- Whishaw, Francis (1842). The Railways of Great Britain and Ireland Practically Described and Illustrated. J. Weale. OCLC 828475755.

- Route Specifications – London North Eastern. Network Rail. 2012. Retrieved 28 September 2013.

- "West Hartlepool Harbour and Railway Company". The National Archives. RAIL 730. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

Further reading

- Ransom, Philip John Greer (1990). The Victorian Railway and How It Evolved. Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-434-98083-3.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to West Hartlepool Harbour and Railway. |

- Clarence Railway Railscot