Cognitive analytic therapy

| Psychology |

|---|

| Basic types |

| Applied psychology |

| Lists |

|

Cognitive analytic therapy (CAT) is a form of psychological therapy initially developed in the United Kingdom by Anthony Ryle. This time-limited therapy was developed in the context of the UK's National Health Service with the aim of providing effective and affordable psychological treatment which could be realistically provided in a resource constrained public health system. It is distinctive due to its intensive use of reformulation, its integration of cognitive and analytic practice and its collaborative nature, involving the patient very actively in their treatment.

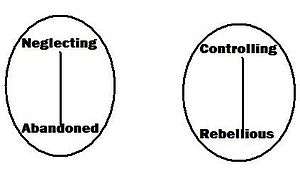

The CAT practitioner aims to work with the patient to identify procedural sequences; chains of events, thoughts, emotions and motivations that explain how a target problem (for example self-harm) is established and maintained. In addition to the procedural sequence model, a second distinguishing feature of CAT is the use of reciprocal roles (RRs). These identify problems as occurring between people and not within the patient. RRs may be set up in early life and then be replayed in later life; for example someone who as a child felt neglected by parents perceived as abandoning might be vulnerable to feelings of abandonment in later life (or indeed neglect themselves).[1]:244–245

Sources and origins

As the name implies, CAT evolved as an integrative therapy based on ideas from cognitive and analytic therapies. CAT was also influenced in part by George Kelly's constructivism. Kelly had developed personal construct theory and the repertory grid method, and Kelly's approach to therapy "offered a model of nonauthoritarian practice" that psychotherapist Anthony Ryle found appealing.[2]:197

Ryle, a general practitioner and analytically trained psychotherapist, was undertaking research into psychotherapy practice using repertory grids in the 1970s. He found that the themes eventually addressed in analytic work were in fact present in transcripts from the very first sessions.[2]:196 However the slow, exploratory nature of traditional analytic therapy meant that these were not always addressed early and assertively, with the result that therapy, while effective, took a long time to produce results. He proposed a shorter, more active form of therapy which integrated elements from cognitive therapy practice (such as goal setting and Socratic questioning) into analytic practice.[3] This would include explicitly formulating the problems experienced by the patient, and sharing this formulation with the patient to engage them in psychotherapy as a co-operative enterprise.[4]

Subsequently CAT has been influenced by ideas from the work of Vygotsky and Bakhtin. From Vygotsky come concepts such as the zone of proximal development (ZPD) and scaffolding.[5] The ZPD implies that new tasks set for the patient (for example, tolerating anxiety about social situations) should extend what they do beyond their current capabilities, but only by a small and achievable amount. Scaffolding involves the therapist providing support for the patient's efforts to change, but varying this level of support as the patient's needs change.

Bakhtin provided concepts such as dialogism from which come techniques such as Dialogical Sequence Analysis. This is a structured attempt to identify and visually display sequences of behaviour, thinking, and emotions so that the patient becomes more aware of these and can start to modify them.[6]

In practice

.jpg)

The model emphasises collaborative work with the client, and focuses on the understanding of the patterns of maladaptive behaviours. The aim of the therapy is to enable the client to recognise these patterns, understand their origins, and subsequently to learn alternative strategies in order to cope better.

The approach is always time-limited, typically taking place over 8-24 weekly sessions (the precise number being agreed at the start of therapy). Sixteen sessions is probably the most common length. In the first quarter of the therapy (the Reformulation phase) the therapist collects all the relevant information, asking the patient about present day problems and also earlier life experiences. At that point the therapist writes a reformulation letter to the client. This letter summarises the therapist's understanding of the client's problems. Particular attention is given to understanding the connection between childhood patterns of behaviour and their impact on adult life. The letter is agreed between patient and therapist and forms the basis for the rest of the work.

After the reformulation letter the patient may be asked to complete diaries or rating sheets to record the occurrence of problems and their context. During this period (known as the Recognition phase) patient and therapist construct a diagrammatic formulation to illustrate the unhelpful procedures which maintain problems for the patient. The aim of this phase is to enable the patient to recognise when and how problems occur.[1]:247

In the second half of the therapy work moves into the Revision phase, where patient and therapist identify and practice "exits" from the procedural diagram established in the previous phase. For example, a problematic procedure might move a patient from feeling angry to taking an overdose. An exit might involve expressing the anger in some way as an alternative to self-injuring behaviour.

At the end of the therapy, patient and therapist each write "goodbye letters" which they exchange, summarising what has been achieved in the therapy and what remains to be done. After the end of the agreed number of weekly sessions, planned follow-up sessions take place to monitor and support the changes that have been made. Typically, a 16-session CAT might be followed up by a single session one month after the end of therapy, and a final one three months later.[1]:248

The evidence base

CAT has been the subject of a number of research studies published in peer-reviewed journals. These include randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and other kinds of study. The approach is too new for any systematic reviews of RCTs to have been conducted, and therefore is not yet explicitly recommended by name by the UK National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). However NICE has recommended that there should be further research of CAT, for example in borderline personality disorder.[7] A review of CAT research evidence published in 2014 reported that although there were five randomised controlled trials published, research evidence into the approach was dominated by small-scale, practice-based studies. These tended to be with complex and severe clinical groups; 44% of studies reviewed involved personality disorder.[8] A review of CAT looking back over the 30 years to its beginnings[9] contains a meta-analysis of 11 outcome studies of CAT. The overall number of patients treated in the studies was 324 and the average effect size across all studies was 0.83 (95% confidence interval 0.66-1.00). This is a large effect and suggests that CAT is efficacious in treating mental health problems.

Evidence from randomised controlled trials

CAT has been shown to lead to subjective improvement in people with anorexia nervosa.[10][11] It has also been shown to produce significant improvements in adolescents with a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder.[12] A different trial suggested that CAT for adult patients with personality disorders also showed improvements in symptoms and interpersonal functioning, as against controls who deteriorated on these measures.[13] CAT has also been shown to improve patients' management of diabetes.[14] An RCT of the use of a CAT-informed assessment for young people who had self-harmed suggested that it was effective in increasing rates of attendance at community follow-up.[15]

Evidence from other methodologies

Comparative studies have suggested CAT to be at least as effective as other forms of brief psychotherapy,[16] person-centred therapy and cognitive behavioural therapy,[17] and interpersonal psychotherapy.[18]

Case series and single case studies have also been published describing the use of CAT in:

- Depression[19][20]

- Dissociative psychosis[21][22]

- The treatment of offenders[23]

- Brain injury[24]

- Deliberate self-harm[25]

- Dissociative identity disorder[26]

- Histrionic personality disorder[27]

- Panic disorder[28]

- Psychological problems in multiple sclerosis[29]

- With carers of people with dementia[30][31]

- Morbid jealousy[32]

- Borderline personality disorder[33][34][35]

- Paranoid personality disorder[36]

- Survivors of child sexual abuse[37][38][39]

Notes

- 1 2 3 Denman, Chess (July 2001). "Cognitive–analytic therapy". Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 7 (4): 243–252. doi:10.1192/apt.7.4.243.

- 1 2 Ryle, Anthony (2005). "Cognitive analytic therapy". In Norcross, John C.; Goldfried, Marvin R. Handbook of psychotherapy integration. Oxford series in clinical psychology (2nd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 196–217. ISBN 0195165799. OCLC 54803644.

- ↑ Ryle, Anthony (January 1979). "The focus in brief interpretive psychotherapy: dilemmas, traps and snags as target problems". British Journal of Psychiatry. 134: 46–54. doi:10.1192/bjp.134.1.46. PMID 760923.

- ↑ Leiman, Mikael (April–July 1994). "The development of cognitive analytic therapy". International Journal of Short-Term Psychotherapy. 9 (2-3): 67–81.

- ↑ Vygotsky, L. S. (1987). Thinking and speech. In L. S. Vygotsky, Collected works (vol. 1, pp. 39-285) (R. Rieber & A. Carton, Eds; N. Minick, Trans.). New York: Plenum. (Original works published in 1934, 1960).

- ↑ Leiman, M. (2004). Dialogical sequence analysis. In: H. J. M. Hermans & G. Dimaggio (eds.), The dialogical self in psychotherapy (pp. 255–270). London: Brunner-Routledge.

- ↑ NICE (January 2009). Borderline personality disorder: Treatment and management, NICE guidelines [CG78], p. 30.

- ↑ Calvert, R; Kellett, S (2014). "Cognitive analytic therapy: A review of the outcome evidence base for treatment". Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice. 87 (3): 253–277. doi:10.1111/papt.12020.

- ↑ Ryle, A; Kellett, S; Hepple, J; Calvert, R (2014). "Cognitive analytic therapy at 30". Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 20 (4): 258–268. doi:10.1192/apt.bp.113.011817.

- ↑ Treasure, J; Ward, A (1997). "Cognitive analytical therapy in the treatment of Anorexia nervosa". Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy. 4 (1): 62–71. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-0879(199703)4:1<62::AID-CPP114>3.0.CO;2-Y.

- ↑ Dare, C.; Eisler, I.; Russell, G.; Treasure, J.; Dodge, L. (2001). "Psychological therapies for adults with anorexia nervosa: Randomised controlled trial of out-patient treatments". British Journal of Psychiatry. 178: 216–221. doi:10.1192/bjp.178.3.216.

- ↑ Chanen, A; McCutcheon, LK; Germano, D; Nistico, H; Jackson, HJ; McGorry, PM (2009). "The HYPE clinic: an early intervention for borderline personality disorder". Journal of Psychiatric Practice. 15 (3): 163–172. doi:10.1097/01.pra.0000351876.51098.f0.

- ↑ Clarke, S; Thomas, P; James, K (2013). "Cognitive analytic therapy for personality disorder: randomised controlled trial". British Journal of Psychiatry. 202 (2): 129–134. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.112.108670.

- ↑ Fosbury, J; Bosley, C; Ryle, A; Sonksen, P; Judd, S (1997). "A trial of cognitive analytic therapy in poorly controlled type 1 diabetes patients". Diabetes Care. 20 (6): 959–964. doi:10.2337/diacare.20.6.959.

- ↑ Ougrin, D.; Zundel, T.; Ng, A.; Banarsee, R.; Bottle, A.; Taylor, E. (2011). "Trial of therapeutic assessment in London: randomised controlled trial of therapeutic assessment versus standard psychosocial assessment in adolescents presenting with self-harm". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 96: 148–153. doi:10.1136/adc.2010.188755.

- ↑ Mann, J & Goldman, R (1982). A casebook in time-limited psychotherapy. New York: McGraw Hill.

- ↑ Marriott, M; Kellett, S (2009). "Evaluating a cognitive analytic therapy service: practice-based outcomes and comparisons with person-centred and cognitive behavioural therapies". Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice. 82: 57–72. doi:10.1348/147608308X336100.

- ↑ Bell (1996)

- ↑ Bennett, D (1994). "Readiness to change—the impact of reformulation: a case example of cognitive analytic therapy". International Journal of Short-Term Psychotherapy. 9: 83–91.

- ↑ Dunn, M.; Golynkina, K.; Ryle, A.; Watson, J. P. (1997). "A repeat audit of the Cognitive Analytic Therapy Clinic at Guy's Hospital". Psychiatric Bulletin. 21: 165–168. doi:10.1192/pb.21.3.165.

- ↑ Brockman, B.; Poynton, A.; Ryle, A.; Watson, J. P. (1987). "Effectiveness of time-limited therapy carried out by trainees: Comparison of two methods". British Journal of Psychiatry. 151: 602–610. doi:10.1192/bjp.151.5.602.

- ↑ Graham & Thavasotby (1995)

- ↑ Pollock, P; Belshaw, T (1998). "Cognitive analytic therapy for offenders". Journal of Forensic Psychiatry. 9 (3): 629–642. doi:10.1080/09585189808405378.

- ↑ Yeates et al. (2008)

- ↑ Cowmeadow, P (1994). "Deliberate self-harm and cognitive analytic therapy". International Journal of Short-Term Psychotherapy. 9 (2-3): 135–150.

- ↑ Kellett (2005)

- ↑ Kellett, S (2007). "A time series evaluation of the treatment of histrionic personality disorder with cognitive analytic therapy". Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice. 80 (3): 389–405. doi:10.1348/147608306X161421.

- ↑ Tzouramanis, P.; et al. (2010). "Evaluation of cognitive-analytic therapy (CAT) outcome in patients with panic disorder". Psychiatrike. 21 (4): 287–293.

- ↑ Adamopoulou, A (2006). An evaluation of cognitive analytic therapy for psychological problem in patients with multiple sclerosis. Multiple Sclerosis, vol. 12, supplement 1, p. S106.

- ↑ Hamill, M.; Mahony, K. (2011). "'The long goodbye': cognitive analytic therapy with carers of people with dementia". British Journal of Psychotherapy. 27: 292–304. doi:10.1111/j.1752-0118.2011.01243.x.

- ↑ This study has also been incorporated into the NICE guidance for dementia: NICE (January 2011), Psychotherapy Service Provision for Carers of People with Dementia (website).

- ↑ Kellett, S.; Totterdell, P. (2013). "Taming the green-eyed monster: temporal responsivity to cognitive behavioural and cognitive analytic therapy for morbid jealousy". Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice. 86: 52–69. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8341.2011.02045.x.

- ↑ Kellett, S.; Bennett, D.; Ryle, T.; Thake, A. (2013). "Cognitive analytic therapy for borderline personality disorder: therapist competence and therapeutic effectiveness in routine practice". Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy. 20: 216–225. doi:10.1002/cpp.796.

- ↑ Ryle, A.; Golynkina, K. (2000). "Effectiveness of time-limited cognitive analytic therapy of borderline personality disorder: factors associated with outcome". British Journal of Medical Psychology. 73: 197–210. doi:10.1348/000711200160426.

- ↑ Wildgoose, A.; Clarke, S.; Waller, G. (2001). "Treating personality fragmentation and dissociation in borderline personality disorder: a pilot study of the impact of cognitive analytic therapy". British Journal of Medical Psychology. 74: 47–55. doi:10.1348/000711201160795.

- ↑ Kellett, S.; Hardy, G. (2013). "Treatment of paranoid personality disorder with cognitive analytic therapy: a mixed methods single case experimental design". Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy. 21: 452–464. doi:10.1002/cpp.1845.

- ↑ Clarke, S.; Llewelyn, S. (1994). "Personal constructs of survivors of childhood sexual abuse receiving cognitive analytic therapy". British Journal of Medical Psychology. 67: 273–289. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8341.1994.tb01796.x.

- ↑ Clarke, S.; Pearson, C. (2000). "Personal constructs of male survivors of childhood sexual abuse receiving cognitive analytic therapy". British Journal of Medical Psychology. 73: 169–177. doi:10.1348/000711200160408.

- ↑ Calvert, R., Kellet, S. & Hagan, T (2015) Group cognitive analytic therapy for female survivors of childhood sexual abuse. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. DOI 10.1111/bjc.12085

Further reading

- Ryle, A (1990) Cognitive Analytic Therapy: Active Participation in Change. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

- Ryle, A (1995). Cognitive Analytic Therapy: Developments in Theory and Practice. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

- Ryle, A (1997). Cognitive Analytic Therapy and Borderline Personality Disorder: The Model and the Method. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

- Ryle, A & Kerr, I (2002). Introducing Cognitive Analytic Therapy: Principles and Practice. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.