Congregation Beth Jacob Ohev Sholom

| Beth Jacob Ohev Sholom | |

|---|---|

| Basic information | |

| Location |

284 Rodney Street, Brooklyn, New York |

| Geographic coordinates | 40°42′28″N 73°57′24″W / 40.70765°N 73.9568°WCoordinates: 40°42′28″N 73°57′24″W / 40.70765°N 73.9568°W |

| Affiliation | Orthodox Judaism |

| Status | Active |

| Leadership |

Rabbi: Joshua Fishman (retired) President: Martin S. Needelman[1] |

| Architectural description | |

| Completed | 1957[1] |

Congregation Beth Jacob Ohev Sholom (also known as "Congregation Beth Jacob Ohev Shalom")[2] ("House of Jacob Lover of Peace") is an Orthodox synagogue located at 284 Rodney Street in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, New York.[3] It is the oldest Orthodox congregation on Long Island (including Brooklyn and Queens), and one of the last remaining non-Hasidic Jewish institutions in Williamsburg.[1]

The congregation was formed in 1869 by German Jews as an Orthodox breakaway from an existing Reform congregation.[1] It constructed its first building on Keap Street in 1870.[4] In 1904 it merged with Chevra Ansche Sholom, and took the name Congregation Beth Jacob Anshe Sholom. The following year it constructed a new building at 274–276 South Third Street, designed by George F. Pelham.[5]

The congregation's building was expropriated and demolished to make way for the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway in the 1950s.[3] It combined with another congregation in a similar situation, and, as Congregation Beth Jacob Ohev Sholom, constructed a new building at 284 Rodney Street, just south of Broadway, in 1957.[3]

Joshua Fishman became rabbi in 1971. With changing demographics, attendance at services, which had been 700 in the 1970s, fell to two dozen by 2010.[1]

Early history

The congregation was founded as Beth Jacob in 1869,[6] by more traditional members of an existing Reform German Jewish synagogue,[1] the Keap Street Temple.[7] They objected to the installation and use of a pipe organ to accompany Yom Kippur services, which was forbidden by halakha (Jewish law), and seceded and created their own congregation.[1] The new congregation was formally incorporated on October 1 of that year,[4] and first worshiped in a house.[1][8] In 1870, Beth Jacob purchased a 23-foot (7.0 m) by 95-foot (29 m) lot at what is now 326 Keap Street (than Tenth Street) for $150 (today $2,800) in cash and a mortgage of $1,050 (today $19,700), and constructed a building there,[4] at a cost of around $6,000 (today $112,000).[8] Men and women sat separately, and the sanctuary had seating for 164 men on the main floor and 135 women in the gallery. Services were generally held only on Shabbat and the Jewish holidays.[4] The first spiritual leader was Rabbi Dresser, and he was succeeded by Lewis Lewinski (or Levinsky).[8][9]

In its early years, the congregation's financial situation was precarious. The building was located ten blocks from where most of the congregants and potential congregants lived (on Grand Street, near the ferry docks), and attendance was low. Even on the High Holy Days, the sanctuary was rarely more than half full. The synagogue employed a rabbi, gabbai, and cantor, and annual expenses often exceeded the congregation's income (which came primarily from the sale of seats). To remain solvent, the congregation borrowed money against the equity in the building: $2,000 (today $53,000) in 1888, and another $2,000 in 1894.[4]

The congregation was also marked by public controversies and factionalism. In January 1887, during a heated discussion at a congregational business meeting, one member addressed two others with the informal German "du" (rather than the formal "Sie"), which was considered impolite. Despite attempts by then-rabbi Lewinksi to intervene, the two men beat the first, knocked him to the ground, and "trampled upon" him.[9] The two men were subsequently charged with "assault in the third degree".[9]

Lewinski was succeeded that year as rabbi by Hyman Rosenberg, and in October of the same year a new secretary was elected, in a close-fought battle between two factions. When it was time for the former secretary to hand over the financial books, a member, Simon Freudenthal, was alleged to have grabbed them, jumped out a window, and ran away with them. When he returned, he refused to say why he took them, and insisted he would keep them. A warrant was issued for his arrest on the charge of larceny, and he was released on bail.[10] Ten days later the synagogue president, American Civil War veteran Colonel Solomon Monday,[11] was arrested and charged in turn with libel, for allegedly claiming that Freudenthal stole "sacred books".[12] Monday, in turn, had Freudenthal charged in November with stealing $8 (today $210) worth of "sacred books" during "divine service".[13] Later that month both cases were dismissed.[14] In early 1888, another case was brought, and dismissed, over attempts by one faction to expel members of the other faction.[15][16]

In December 1892, the congregation expelled Rosenberg, charging him with eating a piece of pork, which is not kosher. To augment his salary of $400 (today $10,600) a year from Beth Jacob, Rosenberg also worked as an agent for a cigar company. While visiting a customer at a bar, he was alleged to have eaten the pork while partaking of some of the free lunch provided there.[17][18] Rosenberg initially said that while he had drunk a great deal, he had not eaten anything at all,[17] and subsequently stated that he was sure he had not eaten pork, because the bar-keep had sworn in affidavit that there was none in the lunch provided that day.[19] Rosenberg later averred consistently that if he had eaten any pork, it was inadvertently.[18] He also alleged hypocrisy on the part of the members, stating "They are all reformed Jews in private, although orthodox Jews in public."[17]

The rabbi's defenders strongly objected to the decision. His primary supporter, synagogue vice president Louis Jackson, who had broken the story to the press, described the congregation as a "collection of jackasses", with the "chief jackass" being the president Louis Schwartz, who Jackson accused of eating ham himself, and of stealing from the synagogue's charity boxes.[20] Jackson was expelled from the congregation,[20] and subsequently convicted of libel and fined $100 (today $2,600) for making the accusations, while Rosenberg sued the synagogue for his salary.[21] Rosenberg died of pneumonia in April 1893, at the age of 43, his "health and spirits", according to a contemporary New York Times report, "broken" by the expulsion. At the funeral, Jackson berated the congregation's members, who, he charged, had "hounded, hunted, driven [Rosenberg] to a grave of misery", and allegedly threatened to kill one of them with a stone taken from the newly dug grave.[18] Charges were again brought against Jackson, but this time were dismissed, with the Justice stating "it looks as if it were an even thing all around."[22]

A month later, Beth Jacob hired Abraham Salbaum as rabbi.[23] The following year, the synagogue's two-story frame synagogue building at 326 Keap Street, valued at $2,000 (today $55,000), was struck by lighting and almost completely destroyed.[24] The congregation decided to rebuild at the same location.[25]

Early twentieth century

Many working class German Jews moved from the Lower East Side to Williamsburg after the Williamsburg Bridge was completed in 1903, providing access to Manhattan.[1] In January 1904, Beth Jacob merged with Chevra Ansche Sholom, a synagogue that had been founded the year before.[26] The combined congregation took the name Beth Jacob Anshe Sholom. Chevra Ansche Sholom worshiped in a Masonic Temple, and had a number of assets, including two houses at 184–186 South Third Street valued at $6,500 (today $171,000), with a mortgage of $4,500 (today $119,000). At the time, Beth Jacob's own building was valued at $6,000 (today $158,000), with a mortgage of $2,000 (today $53,000).[4]

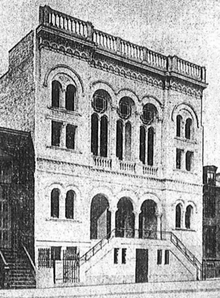

Beth Jacob Anshe Sholom exchanged the deeds for houses at 184–186 South Third Street for a property at 274–276 South Third Street in June 1905.[27] It hired architect George F. Pelham to draw up plans for a new building, instructing him to copy the prominent Congregation Shaaray Tefila building on Manhattan's West 82nd Street, designed by Arnold Brunner, and known as the "West End Synagogue".[5] Features of the new design included seating for almost 1,000 in the main sanctuary,[28] a Talmud Torah for Hebrew language instruction in the basement, electric lighting, and steam heating.[5] Construction was expected to cost $75,000 (today $1,980,000).[29] Beth Jacob Anshe Sholom erected the building at 274–276 South Third Street, and sold Beth Jacob's building at 326 Keap Street to the North Side Chevre, a new congregation.[7]

Ground was broken in June 1905,[30] the cornerstone was laid in September,[29] and the new building was dedicated by then-rabbi Dr. H. Veld on September 9, 1906,[31] in time for High Holy Day services to be held there that year.[27] The actual cost of construction was around $60,000 (today $1,580,000), of which $35,000 (today $920,000) was raised through sale of seats and donations, and the rest via a mortgage. The improved premises attracted many new members.[27]

In February 1907, the congregation created a four-room Talmud Torah. In September of that year Samuel Rabinowitz was hired as rabbi for a three-year term, renewed in 1910 for another three years. A "junior congregation" was created from the members of the Talmud Torah. They elected, as their first "pupil rabbi", Harry Halpern, who later served for five decades as rabbi of the East Midwood Jewish Center.[27]

Rabinowitz resigned in indignation in May 1912, stating the trustees did not live up to the terms of his contract, after Herman Heisman, chairman of the synagogue's board of trustees, hired an assistant rabbi, whose services Rabinowitz objected to.[32] Rabinowitz purchased for $50,000 (today $1,230,000) a church building at South 5th Street and Marcy Avenue, and started his own synagogue there.[27][32] His first Saturday services had an attendance of 1,200, a third of whom were his former congregants, and he stated that "his flock" would soon join him.[32]

Rabinowitz was succeeded as rabbi of Beth Jacob Anshe Sholom in December 1912 by Wolf Gold.[27][33] Born in Szczecin, Poland (then Stettin, Germany) in 1889, he was the descendant of at least eight generations of rabbis, and received his own rabbinic ordination in 1906, at age 17.[34] He emigrated to the United States the following year, and served as rabbi of congregations in Chicago, Illinois and Scranton, Pennsylvania before coming to Williamsburg.[33][34]

A strong proponent of Religious Zionism, Gold helped found in New York the first branch of Mizrahi (the Religious Zionists of America) in the United States in 1914 (he would subsequently assist in the founding of many of its other branches in North America).[34] That year, the congregation purchased for the growing Talmud Torah the First United Presbyterian Church building at South 1st and Rodney Streets, at a cost of $20,050 (today $474,000). Many classrooms were added in the lower auditorium, and the building was dedicated as the "Talmud Torah of Williamsburg" in December.[11]

In 1917, Gold was one of the founders of Yeshiva Torah Vodaas, and was its first president.[34] He would serve at Beth Jacob Anshe Sholom until 1919, moving to a pulpit in San Francisco.[34] That year the congregation had 155 member families.[35] Gold would emigrate to Palestine in 1935, and was one of the signatories of the Israeli Declaration of Independence.[34]

Gold was succeeded as rabbi by Solomon Golobowsky.[11] The congregation had decided by 1918 that the Talmud Torah should become independent: during Golobowsky's tenure, in 1921, it demolished the church building housing the school, and built in its place a new building, with 18 classrooms and an auditorium. The school was incorporated as the "Hebrew School of Williamsburg", and title to the building and property was transferred from the synagogue to it in July of that year. The school in turn assumed a mortgage of $15,000 (today $200,000) and additional debts of around $10,700 (today $140,000).[27]

Isaac Bunin succeeded Golobowsky as rabbi in December 1926.[11] Born in Malistovka, Krasnopoli (near Mogilev, Belarus) in 1882, he had emigrated to the United States in 1923.[36] While practicing as a rabbi in Russia, he issued a responsum in 1908 that permitted Jews to shoot—on the Sabbath—anarchist communists who terrorized local Jewish communities, and extorted "contributions" from them.[37] Before coming to Beth Jacob Anshe Sholom he served as rabbi in Trenton, New Jersey, where he was instrumental in the creation of the re-established Dr. Theodor Herzl's Zion Hebrew School (opened October 1926).[38]

Post world war II

Following World War II and the Holocaust, large numbers of Hasidic and haredi Jewish refugees immigrated to Williamsburg. The congregation initially had poor relations with these groups, but these later improved with some segments of the Hasidic community.[1] The synagogue celebrated Bunin's Silver Jubilee as rabbi in March, 1951.[39] His work Hegyonot Yitzhak was published in 1953.[37]

The old Jewish area of Williamsburg east of Broadway was strongly impacted by the construction of the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway in the 1950s. The congregation's building was expropriated and demolished. It joined with another large Ashkenazi synagogue in the same situation, and in 1957 the merged congregations constructed the current building at the edge of the "Jewish Triangle", just west of Broadway.[1][3] In 1965, Chaim A. Pincus was the rabbi.[40]

Joshua Fishman, described by George Kranzler as "a renowned scholar and orator," became the rabbi of the congregation in 1971.[1][3] He also served from 1982 as head of Torah Umesorah – National Society for Hebrew Day Schools.[1][41][42] At the time Fishman became rabbi, as many as 700 people would attend Beth Jacob Ohev Sholom's services.[1]

One of the members in the 1990s and 2000s was Marty Needleman. He was project director for Brooklyn Legal Services, which provided legal services to low-income Brooklyn residents, and was a member of the executive committees of both the synagogue and of Los Sures, a Williamsburg community-based housing group.[43] Another notable congregant is Steve Cohn, the Democratic District Leader and lawyer whose father was involved with the synagogue, and who had his Bar Mitzvah there.[1]

Samuel Heilman wrote in 1996 that Beth Jacob Ohev Sholom was one of four Williamsburg institutions that served to "anchor the community around them", and "in effect geographically engulf and cancel" the ability of prominent local churches to "dominate the neighborhood".[2] By the mid-1990s, however, the synagogue attracted only 300 to 400 generally elderly Ashkenazi men and women for High Holy Day services, most of whom lived in "public high rise projects", and Fishman doubted that Williamsburg's only remaining Orthodox Nusach Ashkenaz synagogue still holding regular services would survive.[3] By 2010, Shabbat attendance was around two dozen worshipers, and weekday attendance half that.[1]

As of 2010, Beth Jacob Ohev Sholom was the oldest Orthodox congregation on Long Island (including Brooklyn and Queens), and, according to Brooklyn Eagle journalist Raanan Geberer, "one of the few remnants of the non-Hasidic Jewish community that thrived in Williamsburg until the 1960s". No Conservative or Reform synagogues presently exist in the neighborhood, Rabbi Fishman retired in 2014. The president is Martin S. Needelman.[1]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Geberer (2010).

- 1 2 Heilman (2006), p. 223.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Kranzler(1995), p. 163.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Abelow (1948), p. 196.

- 1 2 3 Kaufman (1999), pp. 186–189.

- ↑ According to Geberer (2010), Brooklyn Eagle (September 27, 1891), p. 19, and Abelow (1948), p. 196, which says it "dates back to October 1, 1869, when the certificate of incorporation of Beth Jacob was obtained, approved October 13, 1869 by Justice Gilbert of the Supreme Court". According to Abelow (1937), p. 53, it was founded in 1864. According to the American Jewish Year Book (1899–1900), p. 184, it was founded in 1871.

- 1 2 Abelow (1937), p. 53.

- 1 2 3 Brooklyn Eagle (September 27, 1891), p. 19.

- 1 2 3 Brooklyn Eagle (January 10, 1887), p. 4.

- ↑ Brooklyn Eagle (October 18, 1887), p. 6.

- 1 2 3 4 Abelow (1948), p. 233.

- ↑ Brooklyn Eagle (October 28, 1887), p. 6.

- ↑ Brooklyn Eagle (November 16, 1887), p. 4.

- ↑ Brooklyn Eagle (November 28, 1887), p. 3.

- ↑ Brooklyn Eagle (March 8, 1888), p. 6.

- ↑ Brooklyn Eagle (March 14, 1888), p. 2.

- 1 2 3 Brooklyn Eagle (December 16, 1892), p. 1.

- 1 2 3 The New York Times (April 19, 1893), p. 1.

- ↑ Brooklyn Eagle (December 17, 1892), p. 10.

- 1 2 Brooklyn Eagle (January 12, 1893), p. 5.

- ↑ Brooklyn Eagle (February 3, 1893), p. 10.

- ↑ Brooklyn Eagle (May 25, 1893), p. 12.

- ↑ Brooklyn Eagle (May 9, 1893), p. 10. The Brooklyn Eagle (September 5, 1894), p. 2, gives his name as "S. Baum".

- ↑ Brooklyn Eagle (July 15, 1894), p. 1.

- ↑ Brooklyn Eagle (September 5, 1894), p. 2.

- ↑ According to Abelow (1948), p. 196. Abelow (1937), p. 53, calls it "Anshe Sholom synagogue", and says it was founded in 1902.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Abelow (1948), p. 198.

- ↑ According to Kaufman (1999), pp. 186–189. A contemporary account, Brooklyn Eagle, September 10, 1906, p. 22, gives the seating capacity as 850.

- 1 2 Evening Post (New York), September 18, 1905, p. 7.

- ↑ Evening Post (New York), July 29, 1905, p. 8.

- ↑ Brooklyn Eagle, September 10, 1906, p. 22.

- 1 2 3 The Sun (New York), June 17, 1912, p. 5.

- 1 2 Brooklyn Eagle, December 9, 1912, p. 5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Sherman (1996), p. 78.

- ↑ American Jewish Year Book (1919–1920), p. 440.

- ↑ Cohen (1989), p. 53.

- 1 2 Shapiro (2008), footnote 22.

- ↑ Landman (1943), Vol. 10, p. 301, Pomdore (1929), Chapter VII, section IX. The Jews – 1860, and Hughes (1929), Chapter XIV, section IV. Other Schools.

- ↑ Johnson (1951), p. 13. Teitz Blau (2001), p. 317, has a picture of Bunin attending a December 1952 Union of Orthodox Rabbis celebration. However, Abelow (1948), p. 233, states that he "recently passed away".

- ↑ Powledge (1965), p. 48.

- ↑ Oser (2008).

- ↑ Carper & Hunt (2009), p. 443.

- ↑ McKenna (1992), p. 28.

Citations

- Abelow, Samuel Philip. History of Brooklyn Jewry, Scheba Publishing Company, 1937.

- Abelow, Samuel P., "The Jews of Williamsburg", in Hurwitz, Solomon Theodore Halivy. The Jewish Forum: A Monthly Magazine, Volume 31, The Jewish Forum Publishing Co., 1948.

- American Jewish Committee. ""Directory of Local Organizations"" (PDF). (2.12 MB), American Jewish Year Book, Jewish Publication Society, Volume 1 (1899–1900).

- American Jewish Committee. ""Directories"" (PDF). (6.06 MB), American Jewish Year Book, Jewish Publication Society, Volume 21 (1919–20).

- Brooklyn Eagle, no byline:

- "Cohen Kicked. A Fight in an Eastern District Synagogue.", Brooklyn Eagle, January 10, 1887.

- "Stolen Books. The Thief Jumped Through a Synagogue Window.", Brooklyn Eagle, October 18, 1887.

- "A Synagogue in Court. One of the Congregation Makes a Charge of Libel Against Another.", Brooklyn Eagle, October 28, 1887.

- "Irate Israelites. The Troubles of Congregation Beth Jacob in the Eastern District.", Brooklyn Eagle, November 16, 1887.

- "Synagogue Beth Jacob Out Of Court", Brooklyn Eagle, November 28, 1887.

- "Trouble in Beth Jacob. Members of the Congregation Appeal to the Law.", Brooklyn Eagle, March 8, 1888.

- "May Be Expelled. The Court Cannot Prevent a Synagogue From Taking Action.", Brooklyn Eagle, March 14, 1888.

- "Judaism in Brooklyn. The Ancient Faith of Israel and Its Local Adherents.", Brooklyn Eagle, September 27, 1891.

- "How They Regard Ham. Views of Local Rabbis on Mr. Rosenburg's Expulsion.", Brooklyn Eagle, December 16, 1892.

- "Rabbi Rosenberg Stayed at Home, And All Was Very Quiet at the Temple Beth Jacob This Morning", Brooklyn Eagle, December 17, 1892.

- "The Beth Jacob People. They Had an Exiting Time at at Meeting Last Night", Brooklyn Eagle, January 12, 1893.

- "The Beth Jacob Church Fight. Louis Jackson Found Guilty of Criminal Libel.", Brooklyn Eagle, February 3, 1893.

- "A Rabbi for Beth Jacob, And President Schwartz Says Perfect Harmony Now Reigns", Brooklyn Eagle, May 9, 1893.

- "Justice Goetting Discharged Him", Brooklyn Eagle, May 25, 1893.

- "Struck a Synagogue. Lighting's Freak in the Eastern District.", Brooklyn Eagle, July 15, 1894.

- "Real Estate Market. Equal Rights Demanded in the Transfer of Property", Brooklyn Eagle, September 5, 1894.

- "New Synagogue Opened. Handsome House of Worship Dedicated in South Third Street." Brooklyn Eagle, September 10, 1906.

- "New Rabbi Welcomed. Will Take Charge of Street Congregation." Brooklyn Eagle, December 9, 1912.

- Carper, James C.; Hunt, Thomas C. The Praeger Handbook of Religion and Education in the United States, Praeger Publishers, 2009. ISBN 978-0-275-99227-9

- Cohen, Chester G. Shtetl Finder: Jewish Communities in the 19th and early 20th Centuries in the Pale of Settlement of Russia and Poland, and in Lithuania, Latvia, Galicia, and Bukovina, with Names of Residents, Heritage Books, 1989. ISBN 978-1-55613-248-3

- Evening Post (New York), no byline:

- "Notes of Jewish Churches and Communities", The Evening Post (New York), July 29, 1905.

- "Cornerstone of New Synagogue Laid", The Evening Post (New York), September 18, 1905.

- Geberer, Raanan. "Brooklyn’s Oldest Orthodox Synagogue Celebrates Birthday. 1869 Institution Is Survivor Of Non-Hasidic Williamsburg", Brooklyn Eagle, May 17, 2010.

- Heilman, Samuel C. Sliding to the Right: The Contest for the Future of American Jewish Orthodoxy, University of California Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0-520-23136-8

- Hughes, Howard L. "Chapter XIV: Schools and Libraries", A History of Trenton 1679 — 1929, Trenton Historical Society, 1929.

- Johnson, Cecil. "News in Brief: Around the Borough", Brooklyn Eagle, March 13, 1951.

- Kaufman, David. Shul with a Pool: The "synagogue-center" in American Jewish History, Brandeis University Press, University Press of New England, 1999. ISBN 978-0-87451-893-1

- Kranzler, George. Hasidic Williamsburg: A Contemporary American Hasidic Community, Jason Aronson, 1995. ISBN 978-1-56821-242-5.

- Landman, Isaac., "Trenton", The Universal Jewish Encyclopedia, Volume 10, Universal Jewish Encyclopedia Co. Inc., 1943.

- McKenna, Sheila. "Brooklyn Profile/Martin S. Needelman", Newsday (Brooklyn edition), October 1, 1992, p. 28.

- New York Times, no byline:

- Oser, Asher. "Torah Umesorah", Jewish Virtual Library, 2008. Retrieved June 5, 2010.

- Pomdore, Harry J. "Chapter VIII: Churches and Religious Institutions", A History of Trenton 1679 — 1929, Trenton Historical Society, 1929.

- Powledge, Fred. "The Poor Convene in Williamsburg; Meet to Choose Leaders in Antipoverty Campaign", The New York Times, August 25, 1965, p. 48.

- Shapiro, Marc B. "Rabbis and Communism", the Seforim blog, March, 2008.

- Sherman, Moshe D. Orthodox Judaism in America: A Biographical Dictionary and Sourcebook, Greenwood Publishing Group, 1996. ISBN 978-0-313-24316-5

- Sun (New York), no byline:

- "New Synagogue a Success. War in Williamsburg Splits a Jewish Congregation", The Sun (New York), June 17, 1912.

- Teitz Blau, Rivkah. Learn Torah, Love Torah, Live Torah: HaRav Mordechai Pinchas Teitz, the Quintessential Rabbi, KTAV Publishing House, 2001. ISBN 978-0-88125-718-2