Construction of electronic cigarettes

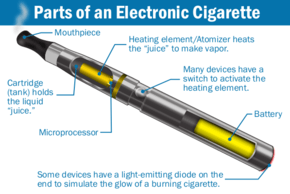

An electronic cigarette is a battery-powered vaporizer.[1] The primary parts that make up an e-cigarette are a mouthpiece, a cartridge (tank), a heating element/atomizer, a microprocessor, a battery, and possibly a LED light on the end.[2] An atomizer comprises a small heating element that vaporizes e-liquid and wicking material that draws liquid onto the coil.[3] When the user pushes a button,[4] or (in some variations) activates a pressure sensor by inhaling, the heating element then atomizes the liquid solution[5] The e-liquid reaches a temperature of roughly 100-250 °C within a chamber to create an aerosolized vapor.[6] The user inhales the aerosol, commonly called vapor, rather than cigarette smoke.[7] The aerosol provides a flavor and feel similar to tobacco smoking.[1]

There are three main types of e-cigarettes: cigalikes, looking like cigarettes; eGos, bigger than cigalikes with refillable liquid tanks; and mods, assembled from basic parts or by altering existing products.[8] As the e-cigarette industry continues to evolve, new products are quickly developed and brought to market.[9] First generation e-cigarettes tend to look like tobacco cigarettes and so are called "cigalikes".[10] Most cigalikes look like cigarettes but there is some variation in size.[11] Second generation devices are larger overall and look less like tobacco cigarettes.[12] Third generation devices include mechanical mods and variable voltage devices.[10] The fourth generation includes Sub ohm tanks and temperature control devices.[13] The power source is the biggest component of an e-cigarette,[14] which is frequently a rechargeable lithium-ion battery.[15]

Use

Function

.jpg)

An e-cigarette is a handheld battery-powered vaporizer that simulates smoking, but without tobacco combustion.[1] Once the user inhales, the airflow activates the pressure sensor, and then the heating element atomizes the liquid solution.[5] Most devices have a manual push-button switch to turn them on or off.[16] E-cigarettes do not turn on by trying to "light" the device with a flame.[4] The e-liquid reaches a temperature of roughly 100-250 °C within a chamber to create an aerosolized vapor.[6] However, variable voltage devices can raise the temperature.[17] A glycerin-only liquid vaporizes at a higher temperature than a propylene glycol-glycerin liquid.[17] Rather than cigarette smoke, the user inhales an aerosol, commonly but inaccurately called vapor.[7] E-cigarettes do not create vapor between puffs.[18]

Perception

Vaping is different than tobacco smoking, but there are some similarities with their behavioral habits, including the hand-to-mouth action and a vapor that looks like cigarette smoke.[1] E-cigarettes provide a flavor and feel similar to smoking.[1] A noticeable difference between the traditional cigarette and the e-cigarette is sense of touch.[1] A traditional cigarette is smooth and light but an e-cigarette is rigid, cold and slightly heavier.[1] Since e-cigarettes are more complex than traditional cigarettes, a learning curve is needed to use them correctly.[19]

Compared to traditional cigarettes, the general e-cigarette puff time is much longer, and requires a more forceful suction than a regular cigarette.[20] The volume of vapor created by e-cigarette devices in 2012 declined with vaping.[1] Thus, to create the same volume of vapor increasing puff force is needed.[1] Later-generation e-cigarettes with concentrated nicotine liquids may deliver nicotine at levels similar to traditional cigarettes.[21] Many e-cigarette versions include a voltage potentiometer to adjust the volume of vapor created.[4] The amount of vapor produced is controlled by the power from the battery, which has led some users to adjust their devices to increase battery power.[6]

Construction

E-cigarettes are usually approximately cylindrical, with many variations: pen-styles, tank-styles etc.[22] Some e-cigarettes look like traditional cigarettes, but others do not.[19] There are three main types of e-cigarettes: cigalikes, looking like cigarettes; eGos, bigger than cigalikes with refillable liquid tanks; and mods, assembled from basic parts or by altering existing products.[8]

The primary parts that make up an e-cigarette are a mouthpiece, a cartridge (tank), a heating element/atomizer, a microprocessor, a battery, and possibly a LED light on the end.[2] The only exception to this are mechanical e-cigarettes (mods) which contain no electronics and the circuit is closed by using a mechanical action switch.[23] E-cigarettes are sold in disposable or reusable variants.[8] Disposable e-cigarettes are discarded once the liquid in the cartridge is used up, while rechargeable e-cigarettes may be used indefinitely.[24] A disposable e-cigarette lasts to around 400 puffs.[25] Reusable e-cigarettes are refilled by hand or exchanged for pre-filled cartridges, and general cleaning is required.[4] A wide range of disposable and reusable e-cigarettes exist.[26] Disposable e-cigarettes are offered for a few dollars, and higher-priced reusable e-cigarettes involve an up-front investment for a starter kit.[19] Some e-cigarettes have a LED at the tip to resemble the glow of burning tobacco.[21] The LED may also indicate the battery status.[1] The LED is not generally used in personal vaporizers or mods.[2]

First-generation e-cigarettes usually simulated smoking implements, such as cigarettes or cigars, in their use and appearance.[10] Later-generation e-cigarettes often called mods, PVs (personal vaporizer) or APVs (advanced personal vaporizer) have an increased nicotine-dispersal performance,[10] house higher capacity batteries, and come in various shapes such as metal tubes and boxes.[27] They contain silver, steel, metals, ceramics, plastics, fibers, aluminum, rubber and spume, and lithium batteries.[28] A growing subclass of vapers called cloud-chasers configure their atomizers to produce large amounts of vapor by using low-resistance heating coils.[29] This practice is known as cloud-chasing.[30] Many e-cigarettes are made of standardized replaceable parts that are interchangeable between brands.[31] A wide array of component combinations exists.[32] Many e-cigarettes are sold with a USB charger.[33] E-cigarettes that resemble pens or USB memory sticks are also sold for those who may want to use the device unobtrusively.[34]

Device generations

As the e-cigarette industry continues to evolve, new products are quickly developed and brought to market.[9]

First-generation

First-generation e-cigarettes tend to look like tobacco cigarettes and so are called "cigalikes".[10] The three parts of a cigalike e-cigarette initially were a cartridge, an atomizer, and a battery.[35] A cigalike e-cigarette currently contains a cartomizer (cartridge atomizer), which is connected to a battery.[35] Most cigalikes look like cigarettes but there is some variation in size.[35]

They may be a single unit comprising a battery, coil and filling saturated with e-juice in a single tube to be used and discarded after the battery or e-liquid is depleted.[10] They may also be a reusable device with a battery and cartridge called a cartomizer.[12] The cartomizer cartridge can be separated from the battery so the battery can be charged and the empty cartomizer replaced when the e-juice runs out.[10]

The battery section may contain an electronic airflow sensor triggered by drawing breath through the device.[12] Other models use a power button that must be held during operation.[12] An LED in the power button or on the end of the device may also show when the device is vaporizing.[36]

Charging is commonly accomplished with a USB charger that attaches to the battery.[37] Some manufacturers also have a cigarette pack-shaped portable charging case (PCC), which contains a larger battery capable of recharging the individual e-cigarette batteries.[38] Reusable devices can come in a kit that contains a battery, a charger, and at least one cartridge.[38] Varying nicotine concentrations are available and nicotine delivery to the user also varies based on different cartomizers, e-juice mixtures, and power supplied by the battery.[22]

These manufacturing differences affect the way e-cigarettes convert the liquid solution to an aerosol, and thus the levels of ingredients, that are delivered to the user and the surrounding air for any given liquid.[22] First-generation e-cigarettes use lower voltages, around 3.7 V.[39]

Second-generation

Second generation devices tend to be used by people with more experience.[12] They are larger overall and look less like tobacco cigarettes.[12] They usually consist of two sections, basically a tank and a separate battery. Their batteries have higher capacity, and are not removable.[10] Being rechargeable, they use a USB charger that attaches to the battery with a threaded connector. Some batteries have a "passthrough" feature so they can be used even while they are charging.[40][41]

Second-generation e-cigarettes commonly use a tank or a "clearomizer".[12] Clearomizer tanks are meant to be refilled with e-juice, while cartomizers are not.[10] Because they're refillable and the battery is rechargeable, their cost of operation is lower.[10] Hovever, they can also use cartomizers, which are pre-filled only.[10]

Some cheaper battery sections use a microphone that detects the turbulence of the air passing through to activate the device when the user inhales.[42] Other batteries like the eGo style can use an integrated circuit, as well as a button for manual activation. The LED shows battery status.[42] The power button can also switch off the battery so it is not activated accidentally.[43] Second generation e-cigarettes may have lower voltages, around 3.7 V.[39] However, adjustable-voltage devices can be set between 3 V and 6 V.[44]

Third-generation

The third-generation includes mechanical mods and variable voltage devices.[45][46] Battery sections are commonly called "mods," referencing their past when user modification was common.[10] Mechanical mods do not contain integrated circuits.[46] They are commonly cylindrical or box-shaped, and typical housing materials are wood, aluminium, stainless steel, or brass.[47] A larger "box mod" can hold bigger and sometimes multiple batteries.[47]

Mechanical mods and variable devices use larger batteries than those found in previous generations.[48] Common battery sizes used are 18350, 18490, 18500 and 18650.[49] The battery is often removable,[46] so it can be changed when depleted. The battery must be removed and charged externally.[46]

Variable devices permit setting wattage, voltage, or both.[40][46] These often have a USB connector for recharging; some can be used while charging, called a "passthrough" feature.[40][50] Mechanical mods do not contain integrated circuits.[46]

The power section may include additional options such as screen readout, support for a wide range of internal batteries, and compatibility with different types of atomizers.[12] Third-generation devices can have rebuildable atomizers with different wicking materials.[10][12] These rebuildables use handmade coils that can be installed in the atomizer to increase vapor production.[48] Hardware in this generation is sometimes modified to increase power or flavor.[51]

The larger battery sections used also allow larger tanks to be attached that can hold more e-liquid.[47] Recent devices can go up to 8 V, which can heat the e-liquid significantly more than earlier generations.[39]

Fourth-generation

A fourth-generation e-cigarette became available in the U.S. in 2014.[21] Fourth-generation e-cigarettes can be made from stainless steel and pyrex glass, and contain very little plastics.[13] Included in the fourth-generation are Sub ohm tanks and temperature control devices.[13]

Atomizer

An atomizer comprises a small heating element that vaporizes e-liquid and a wicking material that draws liquid onto the coil.[3] Along with a battery and e-liquid the atomizer is the main component of every personal vaporizer.[12] A small length of resistance wire is coiled around the wicking material and connected to the integrated circuit, or in the case of mechanical devices, the atomizer is connected directly to the battery through either a 510, 808, or ego threaded connector.[52] 510 being the most common.[52] When activated, the resistance wire coil heats up and vaporizes the liquid, which is then inhaled by the user.[53]

The electrical resistance of the coil, the voltage output of the device, the airflow of the atomizer and the efficiency of the wick all affect the vapor coming from the atomizer.[54] They also affect the vapor quantity or volume yielded.[54]

Atomizer coils made of kanthal usually have resistances that vary from 0.4Ω (ohms) to 2.8Ω.[54] Coils of lower ohms have increased vapor production but could risk fire and dangerous battery failures if the user is not knowledgeable enough about electrical principles and how they relate to battery safety.[55]

Wicking materials vary from one atomizer to another.[56] "Rebuildable" or "do it yourself" atomizers can use silica, cotton, rayon, porous ceramic, hemp, bamboo yarn, oxidized stainless steel mesh and even wire rope cables as wicking materials.[56]

Cartomizers

The cartomizer was invented in 2007, integrating the heating coil into the liquid chamber.[57] A "cartomizer" (a portmanteau of cartridge and atomizer.[58]) or "carto" consists of an atomizer surrounded by a liquid-soaked poly-foam that acts as an e-liquid holder.[3] They can have up to 3 coils and each coil will increase vapor production.[3] The cartomizer is usually discarded when the e-liquid starts to taste burnt, which usually happens when the e-cigarette is activated with a dry coil or when the cartomizer gets consistently flooded (gurgling) because of sedimentation of the wick.[3] Most cartomizers are refillable even if not advertised as such.[3][59]

Cartomizers can be used on their own or in conjunction with a tank that allows more e-liquid capacity.[3] The portmanteau word "cartotank" has been coined for this.[60] When used in a tank, the cartomizer is inserted in a plastic, glass or metal tube and holes or slots have to be punched on the sides of the cartomizer so liquid can reach the coil.[3]

Clearomizers

The clearomizer was invented in 2009 that originated from the cartomizer design.[57] It contained the wicking material, an e-liquid chamber, and an atomizer coil within a single clear component.[57] This allows the user to monitor the liquid level in the device.[57] Clearomizers or "clearos", are like cartotanks, in that an atomizer is inserted into the tank.[61] There are different wicking systems used inside clearomizers.[3] Some rely on gravity to bring the e-liquid to the wick and coil assembly (bottom coil clearomizers for example) and others rely on capillary action or to some degree the user agitating the e-liquid while handling the clearomizer (top coil clearomizers).[3][62] The coil and wicks are typically inside a prefabricated assembly or "head" that is replaceable by the user.[63]

Clearomizers are made with adjustable air flow control.[64] Tanks can be plastic or borosilicate glass.[65] Some flavors of e-juice have been known to damage plastic clearomizer tanks.[65]

Rebuildable atomizers

A rebuildable atomizer or an RBA is an atomizer that allows the user to assemble or "build" the wick and coil themselves instead of replacing them with off-the-shelf atomizer "heads".[10] They are generally considered advanced devices.[66] They also allow the user to build atomizers at any desired electrical resistance.[10]

These atomizers are divided into two main categories; rebuildable tank atomizers (RTAs) and rebuildable dripping atomizers (RDAs).[67]

Rebuildable tank atomizers (RTAs) They have a tank to hold liquid that is absorbed by the wick.[68] They can hold up to 4ml of e-liquid.[69] The tank can be either plastic, glass, or metal.[65] One form of tank atomizers was the Genesis style atomizers.[68] They can use ceramic wicks, stainless steel mesh or rope for wicking material.[68] The steel wick must be oxidized to prevent arcing of the coil.[68] Another type is the Sub ohm tank.[69] These tanks have rebuildabe or RBA kits.[69] They can also use coilheads of 0.2ohm 0.4hom and 0.5ohm.[69] These coilheads can have stainless steel coils.[70]

Rebuildable dripping atomizers (RDAs) are atomizers where the e-juice is dripped directly onto the coil and wick.[71] The common nicotine strength of e-liquids used in RDA's is 3 mg and 6 mg.[71] Liquids used in RDA's tend to have more vegetable glycerin.[71] They typically consist only of an atomizer "building deck", commonly with three posts with holes drilled in them, which can accept one or more coils.[51] The user needs to manually keep the atomizer wet by dripping liquid on the bare wick and coil assembly, hence their name.[71]

Kanthal wire is commonly used in both RDA's and RTA's.[71] They can also use nickel wire or titanium wire for temperature control.[71]

Power

Variable power and voltage devices

Variable devices are variable wattage, variable voltage or both.[40][46] Variable power and/or variable voltage have a electronic chip allowing the user to adjust the power applied to the heating element.[12][46] The amount of power applied to the coil affects the heat produced, thus changing the vapor output.[12][32] Greater heat from the coil increases vapor production.[32] Variable power devices monitor the coil's resistance and automatically adjust the voltage to apply the user-specified level of power to the coil.[72] Recent devices can go up to 8 V.[39]

They are often rectangular but can also be cylindrical.[47] They usually have a screen to show information such as voltage, power, and resistance of the coil.[73] To adjust the settings, the user presses buttons or rotates a dial to turn the power up or down.[32] Some of these devices include additional settings through their menu system such as: atomizer resistance meter, remaining battery voltage, puff counter, and power-off or lock.[74] The power source is the biggest component of an e-cigarette,[14] which is frequently a rechargeable lithium-ion battery.[4] Smaller devices contain smaller batteries and are easier to carry but typically require more repeated recharging.[4] Some e-cigarettes use a long lasting rechargeable battery, a non-rechargeable battery or a replaceable battery that is either rechargeable or non-rechargeable for power.[26] Some companies offer portable chargeable cases to recharge e-cigarettes.[26] Nickel-cadmium (NiCad), nickel metal-hydride (NiMh), lithium ion (Li-ion), alkaline and lithium polymer (Li-poly), and lithium manganese (LiMn) batteries have been used for the e-cigarettes power source.[26]

Temperature control devices

Temperature control devices allow the user to set the temperature.[71] There is a predictable change to the resistance of a coil when it is heated.[75] The resistance changes are different for different types of wires, and must have a high temperature coefficient of resistance.[75] Temperature control is done by detecting that resistance change to estimate the temperature and adjusting the voltage to the coil to match that estimate.[76]

Nickel, titanium, NiFe alloys, and certain grades of stainless steel are common materials used for wire in temperature control.[71] The most common wire used, kanthal, cannot be used because it has a stable resistance regardless of the coil temperature.[75] Nickel was the first wire used because of it has the highest coefficient of the common metals.[75]

The temperature can be adjusted in Celsius or Fahrenheit.[77] The DNA40 and SX350J are common control boards used in temperature control devices.[78] Temperature control can stop dry wicks from burning, or e-liquid overheating.[78]

Mechanical devices

Mechanical PVs or mechanical "mods", often called "mechs", are devices without integrated circuits, electronic battery protection, or voltage regulation.[46] They are activated by a switch.[71] They rely on the natural voltage output of the battery and the metal that the mod is made of often is used as part of the circuit itself.[79]

The term "mod" was originally used instead of "modification".[10] Users would modify existing hardware to get better performance, and as an alternative to the e-cigarettes that looked like traditional cigarettes.[32] Users would also modify other unrelated items like flashlights as battery compartments to power atomizers.[32][47] The word mod is often used to describe most personal vaporizers.[3]

Mechanical PVs have no power regulation and are unprotected.[71] Because of this ensuring that the battery does not over-discharge and that the resistance of the atomizer requires amperage within the safety limits of the battery is the responsibility of the user.[79]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Caponnetto, Pasquale; Campagna, Davide; Papale, Gabriella; Russo, Cristina; Polosa, Riccardo (2012). "The emerging phenomenon of electronic cigarettes". Expert Review of Respiratory Medicine. 6 (1): 63–74. doi:10.1586/ers.11.92. ISSN 1747-6348. PMID 22283580.

- 1 2 3 "Electronic Cigarette Fires and Explosions" (PDF). United States Fire Administration. October 2014. pp. 1–11.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "Vaper Talk – The Vaper's Glossary". Spinfuel eMagazine. 5 July 2013. Retrieved 18 November 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Orellana-Barrios, Menfil A.; Payne, Drew; Mulkey, Zachary; Nugent, Kenneth (2015). "Electronic cigarettes-a narrative review for clinicians". The American Journal of Medicine. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.01.033. ISSN 0002-9343. PMID 25731134.

- 1 2 Rahman MA, Hann N, Wilson A, Worrall-Carter L (2014). "Electronic cigarettes: patterns of use, health effects, use in smoking cessation and regulatory issues". Tob Induc Dis. 12 (1): 21. doi:10.1186/1617-9625-12-21. PMC 4350653

. PMID 25745382.

. PMID 25745382. - 1 2 3 Rowell, Temperance R; Tarran, Robert (2015). "Will Chronic E-Cigarette Use Cause Lung Disease?". American Journal of Physiology. Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology: ajplung.00272.2015. doi:10.1152/ajplung.00272.2015. ISSN 1040-0605. PMID 26408554.

- 1 2 Cheng, T. (2014). "Chemical evaluation of electronic cigarettes". Tobacco Control. 23 (Supplement 2): ii11–ii17. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051482. ISSN 0964-4563. PMC 3995255

. PMID 24732157.

. PMID 24732157. - 1 2 3 Ebbert, Jon O.; Agunwamba, Amenah A.; Rutten, Lila J. (2015). "Counseling Patients on the Use of Electronic Cigarettes". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 90 (1): 128–134. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2014.11.004. ISSN 0025-6196. PMID 25572196.

- 1 2 Glasser, A. M.; Cobb, C. O.; Teplitskaya, L.; Ganz, O.; Katz, L.; Rose, S. W.; Feirman, S.; Villanti, A. C. (2015). "Electronic nicotine delivery devices, and their impact on health and patterns of tobacco use: a systematic review protocol". BMJ Open. 5 (4): e007688–e007688. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-007688. ISSN 2044-6055. PMID 25926149.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Farsalinos, Konstantinos E.; Spyrou, Alketa; Tsimopoulou, Kalliroi; Stefopoulos, Christos; Romagna, Giorgio; Voudris, Vassilis (2014). "Nicotine absorption from electronic cigarette use: comparison between first and new-generation devices". Scientific Reports. 4. doi:10.1038/srep04133. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 3935206

. PMID 24569565.

. PMID 24569565. - ↑ Bhatnagar, A.; Whitsel, L. P.; Ribisl, K. M.; Bullen, C.; Chaloupka, F.; Piano, M. R.; Robertson, R. M.; McAuley, T.; Goff, D.; Benowitz, N. (24 August 2014). "AHA Policy Statement - Electronic Cigarettes". Circulation. 130 (16): 1418–1436. doi:10.1161/cir.0000000000000107.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Hayden McRobbie (2014). "Electronic cigarettes" (PDF). National Centre for Smoking Cessation and Training. pp. 1–16.

- 1 2 3 Konstantinos Farsalinos. "Electronic cigarette evolution from the first to fourth-generation and beyond" (PDF). gfn.net.co. Global Forum on Nicotine. p. 23. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- 1 2 Rom, Oren; Pecorelli, Alessandra; Valacchi, Giuseppe; Reznick, Abraham Z. (2014). "Are E-cigarettes a safe and good alternative to cigarette smoking?". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1340 (1): 65–74. doi:10.1111/nyas.12609. ISSN 0077-8923. PMID 25557889.

- ↑ Garner, Charles; Stevens, Robert (February 2014). "A Brief Description of History, Operation and Regulation" (PDF). Coresta. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- ↑ Kaisar, Mohammad Abul; Prasad, Shikha; Liles, Tylor; Cucullo, Luca (2016). "A Decade of e-Cigarettes: Limited Research & Unresolved Safety Concerns". Toxicology. doi:10.1016/j.tox.2016.07.020. ISSN 0300-483X. PMID 27477296.

- 1 2 Bertholon, J.F.; Becquemin, M.H.; Annesi-Maesano, I.; Dautzenberg, B. (2013). "Electronic Cigarettes: A Short Review". Respiration. 86: 433–8. doi:10.1159/000353253. ISSN 1423-0356. PMID 24080743.

- ↑ "Supporting regulation of electronic cigarettes". www.apha.org. US: American Public Health Association. 18 November 2014.

- 1 2 3 Pepper, J. K.; Brewer, N. T. (2013). "Electronic nicotine delivery system (electronic cigarette) awareness, use, reactions and beliefs: a systematic review". Tobacco Control. 23 (5): 375–384. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051122. ISSN 0964-4563. PMID 24259045.

- ↑ Evans, S. E.; Hoffman, A. C. (2014). "Electronic cigarettes: abuse liability, topography and subjective effects". Tobacco Control. 23 (Supplement 2): ii23–ii29. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051489. ISSN 0964-4563. PMC 3995256

. PMID 24732159.

. PMID 24732159. - 1 2 3 Brandon, T. H.; Goniewicz, M. L.; Hanna, N. H.; Hatsukami, D. K.; Herbst, R. S.; Hobin, J. A.; Ostroff, J. S.; Shields, P. G.; Toll, B. A.; Tyne, C. A.; Viswanath, K.; Warren, G. W. (2015). "Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems: A Policy Statement from the American Association for Cancer Research and the American Society of Clinical Oncology" (PDF). Clinical Cancer Research. 21: 514–525. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2544. ISSN 1078-0432. PMID 25573384.

- 1 2 3 Grana, R; Benowitz, N; Glantz, SA (13 May 2014). "E-cigarettes: a scientific review.". Circulation. 129 (19): 1972–86. doi:10.1161/circulationaha.114.007667. PMC 4018182

. PMID 24821826.

. PMID 24821826. - ↑ Steve K (19 February 2014). "What is an e-Cigarette MOD E-cig 101". Steve K's Vaping World.

- ↑ Franck, C.; Budlovsky, T.; Windle, S. B.; Filion, K. B.; Eisenberg, M. J. (2014). "Electronic Cigarettes in North America: History, Use, and Implications for Smoking Cessation". Circulation. 129 (19): 1945–1952. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.006416. ISSN 0009-7322. PMID 24821825.

- ↑ Oscar Raymundo (27 January 2015). "How to Get Started with E-Cigarettes". The Huffington Post.

- 1 2 3 4 Brown, C. J.; Cheng, J. M. (2014). "Electronic cigarettes: product characterisation and design considerations". Tobacco Control. 23 (Supplement 2): ii4–ii10. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051476. ISSN 0964-4563. PMC 3995271

. PMID 24732162.

. PMID 24732162. - ↑ McQueen, Amy; Tower, Stephanie; Sumner, Walton (2011). "Interviews with "vapers": implications for future research with electronic cigarettes" (PDF). Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 13 (9): 860–7. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntr088. PMID 21571692.

- ↑ SA, Meo; SA, Al Asiri (2014). "Effects of electronic cigarette smoking on human health" (PDF). Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 18 (21): 3315–9. PMID 25487945.

- ↑ Mary Plass (29 January 2014). "The Cloud Chasers". Vape News Magazine.

- ↑ Dominique Mosbergen (5 August 2014). "This Man Is An Athlete In The Sport Of 'Cloud Chasing'". The Huffington Post.

- ↑ Jérôme Cartegini (27 May 2014). "A la découverte de la cigarette électronique". Clubic.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Couts, Andrew (13 May 2013). "Inside the world of vapers, the subculture that might save smokers' lives". Digital Trends. Retrieved 20 November 2013.

- ↑ Alex Hern (21 November 2014). "Now e-cigarettes can give you malware". The Guardian.

- ↑ Schraufnagel, Dean E.; Blasi, Francesco; Drummond, M. Bradley; Lam, David C. L.; Latif, Ehsan; Rosen, Mark J.; Sansores, Raul; Van Zyl-Smit, Richard (2014). "Electronic Cigarettes. A Position Statement of the Forum of International Respiratory Societies". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 190 (6): 611–618. doi:10.1164/rccm.201407-1198PP. ISSN 1073-449X. PMID 25006874.

- 1 2 3 Bhatnagar, A.; Whitsel, L. P.; Ribisl, K. M.; Bullen, C.; Chaloupka, F.; Piano, M. R.; Robertson, R. M.; McAuley, T.; Goff, D.; Benowitz, N. (2014). "Electronic Cigarettes: A Policy Statement From the American Heart Association". Circulation. 130 (16): 1418–1436. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000107. ISSN 0009-7322. PMID 25156991.

- ↑ "The skyrocketing popularity of e-cigarettes: A guide". The Week. 20 August 2012. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ↑ Tim Stevens. "Thanko's USB-powered Health E-Cigarettes sound healthy". Engagdet. Retrieved 18 November 2014.

- 1 2 Terrence O'Brien. "E-Lites electronic cigarette review". Engagdet. Retrieved 18 November 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Crotty Alexander LE, Vyas A, Schraufnagel DE, Malhotra A (2015). "Electronic cigarettes: the new face of nicotine delivery and addiction". J Thorac Dis. 7 (8): E248–51. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2015.07.37. PMC 4561260

. PMID 26380791.

. PMID 26380791. - 1 2 3 4 "Vaper Talk – The Vaper's Glossary page 2". Spinfuel eMagazine. 5 July 2013. Retrieved 18 November 2014.

- ↑ Farsalinos, K. E.; Polosa, R. (2014). "Safety evaluation and risk assessment of electronic cigarettes as tobacco cigarette substitutes: a systematic review". Therapeutic Advances in Drug Safety. 5 (2): 67–86. doi:10.1177/2042098614524430. ISSN 2042-0986. PMC 4110871

. PMID 25083263.

. PMID 25083263. - 1 2 "How does the battery work?". How To Vape. Retrieved 3 October 2014.

- ↑ "Joyetech eCom". PCMag. Ziff Davis. Retrieved 24 November 2014.

- ↑ Tom McBride (11 February 2013). "Vaping Basics – VAPE GEAR". Spinfuel eMagazine. Retrieved 28 September 2015.

- ↑ Daniel Culpan (21 May 2015). "E-cigarettes may only be harmful under 'extreme conditions'". Condé Nast. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Mark Benson (9 January 2015). "Are Third Generation Vaping Devices A Step Too Far?". Spinfuel eMagazine. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Michael Grothaus (1 October 2014). "Trading addictions: the inside story of the e-cig modding scene". Engadget.

- 1 2 Sean Cooper (23 May 2014). "What you need to know about vaporizers". Engadget.

- ↑ "Understanding MilliAmp Hours". Spinfuel eMagazine. 2 January 2014. Retrieved 20 November 2014.

- ↑ "The Vapologist will see you now: Inside New York's first e-cigarette bar". The Week. 11 October 2013. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- 1 2 Eric Larson (25 January 2014). "Pimp My Vape: The Rise of E-Cigarette Hackers". Mashable. Retrieved 22 November 2014.

- 1 2 John Castle (27 January 2014). "E Cigarettes And Clearomizers". Spinfuel eMagazine. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- ↑ EP application 2614731, Yonghai Li, Zhongli Xu, "An atomizer for electronic cigarette", published 17 July 2013

- 1 2 3 Joseph C. Martin, III (2 September 2015). "The World of the [RDA] Coil". Spinfuel eMagazine. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- ↑ "Harding Battery Handbook For" (PDF). Harding Energy, Inc. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-12-27.

- 1 2 Ngonngo, Nancy. "As e-cigarette stores pop up in Twin Cities, so do the questions". Pioneer Press. Retrieved 20 November 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 Mike K (9 June 2015). "What Does The Future Hold For Vaping Technology?". Steve K's Vaping World.

- ↑ "Logic Premium Electronic Cigarettes". PC Magazine. 30 July 2013.

- ↑ "E-Cig Basics: What Is a Cartomizer?". Vape Ranks. Retrieved 19 November 2013.

- ↑ "lgaurejen". 17 February 2015.

- ↑ Greg Olson (29 January 2014). "Smoking going electronic". Civistas Media. Journal-Courier. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- ↑ "Whats the choice between a clearomizer vs atomizer?". DeXinTech. Retrieved 6 February 2014.

- ↑ Arvid Sollom (9 May 2015). "Sub ohm tanks and the end of non hobbyist building". Vape Magazine. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- ↑ VAPE Magazine March EU Special. Vape Magazine. March 2015. p. 50. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- 1 2 3 Lindsay Fox (24 March 2014). "E-Liquid and Tank Safety". EcigaretteReviewed. Retrieved 6 November 2014.

- ↑ "The Rebuildable Atomizer – An Introduction And Overview". Spinfuel Magazine. 7 January 2013. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- ↑ "3 steps to rebuilding atomizers". Vapenews Magazine. Vapenews Magazine. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Erick Potter (16 January 2014). "How to prepare a stainless steel wick and wrap a coil for a Genesis style rebuildable atomizer". Vape Magazine. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Julia Hartley-Barnes (17 September 2015). "Vaping with Julia "Sub Ohm Tanks"". Spinfuel eMagazine. Retrieved 22 September 2015.

- ↑ John Manzione (27 July 2015). "Aspire Triton Full Review". Retrieved 26 September 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Jason Little (13 July 2015). "Guide To Dripping e Liquid". Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- ↑ Tom McBride (28 February 2013). "Taking The Mystery Out Of Variable Wattage". Spinfuel eMagazine. Retrieved 18 November 2014.

- ↑ Beach, Dania (29 January 2014). "Vapor Corp. Launches New Store-in-Store VaporX(R) Retail Concept at Tobacco Plus Convenience Expo in Las Vegas". Wall Street Journal. Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 26 October 2015.

- ↑ "JoyeTech eVic Review". Real Electric Cigarettes Reviews.

- 1 2 3 4 Staff. "Temperature Coefficients and Coil Wires". Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- ↑ Tom McBride (8 December 2015). "Temperature Control Vaping: The Decision Is Yours". Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- ↑ Spinfuel Staff (3 August 2015). "HCigar VT40 Evolv DNA40 Mod". Spinfuel eMagazine. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- 1 2 Tim Hanlon (15 February 2015). "Temperature-controlled e-cigs: The next giant leap in harm reduction of nicotine use?". Gizmag. Retrieved 22 September 2015.

- 1 2 Dale Amann (10 February 2014). "Battery Safety and Ohm's Law". onVaping. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

External links

-

Media related to Electronic cigarettes at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Electronic cigarettes at Wikimedia Commons