Colgan Air Flight 3407

|

A Dash-8 Q400 similar to the aircraft involved. | |

| Accident summary | |

|---|---|

| Date | February 12, 2009 |

| Summary | Stalled during landing approach; crashed into a house |

| Site |

Clarence Center, New York, United States 43°00′42″N 78°38′21″W / 43.011602°N 78.63904°W |

| Passengers | 45 |

| Crew | 4 |

| Fatalities | 50 (all 49 on board; one on the ground) |

| Injuries (non-fatal) | 4 (on the ground) |

| Aircraft type | Bombardier DHC8-402 Q400 |

| Operator |

Colgan Air d/b/a Continental Connection |

| Registration | N200WQ |

| Flight origin | Newark Liberty International Airport, Newark, New Jersey |

| Destination | Buffalo Niagara International Airport, Buffalo, New York |

Colgan Air Flight 3407, marketed as Continental Connection under a codeshare agreement with Continental Airlines, was a scheduled passenger flight from Newark, New Jersey, to Buffalo, New York, which crashed on February 12, 2009. The aircraft, a Bombardier Dash-8 Q400, entered an aerodynamic stall from which it did not recover and crashed into a house in Clarence Center, New York at 10:17 p.m. EST (03:17 UTC), killing all 49 passengers and crew on board, as well as one person inside the house.[1]

The accident triggered a wave of inquiries about the operations of regional airlines in the United States. It was the first fatal airline accident in the U.S. since the crash of Comair Flight 5191 in August 2006, with 49 fatalities.

The National Transportation Safety Board conducted the accident investigation and published a final report on February 2, 2010, which found the probable cause to be the pilots' inappropriate response to the stall warnings.[2]

Families of the accident victims lobbied the U.S. Congress to enact more stringent regulations for regional carriers, and to improve the scrutiny of safe operating procedures and the working conditions of pilots. The Airline Safety and Federal Aviation Administrative Extension Act of 2010 required some of these regulation changes.[3]

Flight details

Colgan Air Flight 3407 (9L/CJC 3407) was marketed as Continental Connection Flight 3407. It was delayed two hours, departing at 9:18 p.m. Eastern Standard Time (EST; 02:18 UTC), en route from Newark Liberty International Airport to Buffalo Niagara International Airport.[4]

The twin-engine turboprop Bombardier Dash 8 Q400, FAA registry N200WQ, was manufactured in 2008 for Colgan.[5]

This was the first fatal accident for a Colgan Air passenger flight since the company was founded in 1991. One previous ferry flight (no passengers) crashed offshore of Massachusetts in August 2003, killing both of the crew on board. The only prior accident involving a Colgan Air passenger flight occurred at LaGuardia Airport, when another plane collided with the Colgan aircraft while taxiing, resulting in minor injuries to a flight attendant.[6]

Captain Marvin Renslow, 47, of Lutz, Florida, was the pilot in command, and Rebecca Lynne Shaw, 24, of Maple Valley, Washington, served as the first officer.[7][8][9] There were two flight attendants: Matilda Quintero and Donna Prisco.

Captain Renslow was hired in September 2005 and had accumulated 3,379 total flight hours, with 111 hours as captain on the Q400. First officer Shaw was hired in January 2008, and had 2,244 hours, 774 of them in turbine aircraft including the Q400.[10]

There were 2 Canadians, 1 Chinese, and 1 Israeli passengers on board. The remaining 46, including the crew members, were American.[11]

Crash

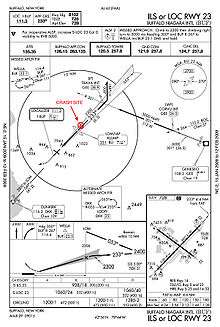

Shortly after the flight was cleared for the runway 23 instrument landing system approach to Buffalo Niagara International Airport, it disappeared from radar. The weather consisted of a wintry mix of light snow, fog and wind of 15 knots. The de-icing system had been turned on 11 minutes after takeoff. Shortly before the crash, the pilots discussed significant ice buildup on the aircraft's wings and windshield.[12][13][14] Two other aircraft reported icing conditions around the time of the crash.

The last radio transmission from the flight occurred when the first officer acknowledged a routine instruction to change to tower frequency. The plane was 3.0 miles (4.8 km) northeast of the radio beacon KLUMP (see diagram) at that time. The crash occurred 41 seconds after that last transmission. Since ATC approach control was unable to get any further response from the flight, the assistance of Delta Air Lines Flight 1998 and US Airways Flight 1452 was requested. Neither was able to spot the missing plane.[15][16][17][18][19]

Following the clearance for final approach, landing gear and flaps (5 degrees) were extended. The flight data recorder (FDR) indicated the airspeed had decayed to 145 knots (269 km/h).[2] The captain then called for the flaps to be increased to 15 degrees. The airspeed continued to slow to 135 knots (250 km/h). Six seconds later, the aircraft's stick shaker activated, warning of an impending stall as the speed continued to slow to 131 knots (243 km/h). The captain responded by abruptly pulling back on the control column, followed by increasing thrust to 75% power, instead of lowering the nose and applying full power, which was the proper stall recovery technique. That improper action pitched the nose up even further, increasing both the g-load and the stall speed. The stick pusher activated ("The Q400 stick pusher applies an airplane-nose-down control column input to decrease the wing angle-of-attack [AOA] after an aerodynamic stall"),[2] but the captain overrode the stick pusher and continued pulling back on the control column. The first officer retracted the flaps without consulting with the captain, making recovery even more difficult.[20]

In its final moments, the aircraft pitched up 31 degrees, then pitched down 25 degrees, then rolled left 46 degrees and snapped back to the right at 105 degrees. Occupants aboard experienced forces estimated at nearly twice that of gravity. The crew made no emergency declaration as they rapidly lost altitude and crashed into a private home at 6038 Long Street,[21] about 5 miles (8.0 km) from the end of the runway, with the nose pointed away from the airport. The aircraft burst into flames as the fuel tanks ruptured on impact, destroying the house of Douglas and Karen Wielinski, and most of the plane. Douglas was killed; his wife Karen and their daughter Jill managed to escape with minor injuries. There was very little damage to surrounding homes, even though the lots in that area are only 60 feet (18.3 meters) wide.[22] The home was close to the Clarence Center Fire Company, so emergency personnel were able to respond quickly. Two of the firefighters were injured. Twelve nearby houses were evacuated.[13][19][23][24][25][26][27]

Victims

A total of 50 people died, including the 49 passengers and crew on board when the aircraft was destroyed, and one resident of the house that was struck. There were four injuries on the ground, including two other people inside the home at the time of the crash. Among the dead were:

- Alison Des Forges, a human rights investigator and an expert on the Rwandan genocide.[11][28]

- Beverly Eckert, who became co-chair of the 9/11 Family Steering Committee and a leader of Voices of September 11 after her husband Sean Rooney was killed in the September 11 attacks. She was en route to Buffalo to celebrate her husband's 58th birthday and award a scholarship in his memory at Canisius High School.[11][29][30]

- Gerry Niewood and Coleman Mellett, jazz musicians who were en route to a concert with Chuck Mangione and the Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra.[11]

- Susan Wehle, the first American female Jewish Renewal cantor.[31]

Reactions

- Colgan Air set up a telephone number for families and friends of those affected to call on February 13, and a family assistance center was opened at the Cheektowaga Senior Center in Cheektowaga CDP, Town of Cheektowaga, New York.[32][33][34] The American Red Cross also opened reception centers in Buffalo and Newark where family members could receive support from mental health and spiritual care workers.[35]

- During the afternoon, the U.S. House of Representatives held a moment of silence for the victims and their families.[36]

- Buffalo's professional ice hockey team, the Buffalo Sabres, held a moment of silence prior to their scheduled game the next night against the San Jose Sharks.[37]

- The University at Buffalo (UB), which lost 11 passengers who were former employees, faculty or alumni, and 12 who were family members of faculty, employees, students or alumni in the crash, also held a remembrance service on February 17, 2009.[38][39] A band with the flight number was worn on UB players' uniforms for the remainder of the basketball season.

- Buffalo State College's 11th President Muriel Howard released a statement regarding the six alumni lost on Flight 3407. Beverly Eckert was a 1975 graduate from Buffalo State.[40]

- On March 4, 2009, New York Governor David Paterson proposed the creation of a scholarship fund to benefit children and financial dependents of the 50 crash victims. The Flight 3407 Memorial Scholarship would cover costs for up to four years of undergraduate study at a SUNY or CUNY school, or a private college or university in New York State.[41]

- The accident was the basis for a PBS Frontline episode on the regional airline industry. Discussed in the episode were issues relating to regional airline regulation, training requirements, safety, and working conditions.[42] Also discussed were the operating principles of regional airlines and the agreements between regional airlines and major airlines.[43]

Investigation

The U.S. National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) began their inquiry on February 13, with a team of 14 investigators.[16][17][44] Both the flight data recorder (FDR) and the cockpit voice recorder (CVR) were recovered and analyzed in Washington, D.C.[19][45]

Data extracted from the FDR revealed the aircraft went through severe pitch and roll oscillations shortly after the extension of flaps and landing gear, which was followed by the activation of the "stick shaker" stall system. The aircraft fell 800 feet (240 m) and then crashed on a northeast heading, opposite of the approach heading to the airport. Occupants experienced increased G-force, estimated to be two times that of gravity, prior to impact.[13][19][26][46][47]

Freezing temperatures made it difficult to access crash debris. Portable heaters were used to melt ice left in the wake of the firefighting efforts. Human remains were carefully removed, and then finally identified, over a period of several weeks. The cockpit had sustained the greatest impact force, while the main cabin was mostly destroyed by the ensuing fireball. Passengers in the rear section were still strapped in their seats.[26][46][48]

The autopilot was in control until it automatically disconnected when the stall warning stick shaker activated. The NTSB found no evidence of severe icing conditions, which would have required the pilots to fly manually.[49] Colgan recommends pilots fly manually in icing conditions, and requires them to do so in severe icing conditions. In December 2008, the NTSB issued a safety bulletin about the danger of keeping the autopilot engaged during icing conditions. Flying the plane manually was essential to ensure pilots would be able to detect changes in the handling characteristics of the airplane, which are a warning sign of ice accumulation.[50][51][52]

After the captain reacted inappropriately to the stick shaker stall warning, the stick pusher activated. As designed, it pushed the nose down when it sensed a stall was imminent, but the captain again reacted improperly and overrode that additional safety device by pulling back again on the control column, causing the plane to stall and crash.[53] Bill Voss, president of Flight Safety Foundation, told USA Today that it sounded like the plane was in "a deep stall situation".[54]

On May 11, 2009, information was released about Captain Renslow's training record. He had failed three "check rides",[55] including some at Gulfstream International in its pay to fly program, and it was suggested that he may not have been adequately trained to respond to the emergency that led to the airplane's fatal descent.[55] Investigators examined possible crew fatigue. The captain appeared to have been at Newark airport overnight, prior to the day of the 9:18 pm departure of the accident flight. The first officer commuted from Seattle to Newark on an overnight flight.[2][56] These findings during the investigation led the FAA to issue a "Call to Action" for improvements in the practices of regional carriers.[57]

In response to questioning from the NTSB, Colgan Air officials acknowledged both pilots apparently were not paying close attention to the aircraft's instruments and did not properly follow the airline's procedures for handling an impending stall. "I believe Capt. Renslow did have intentions of landing safely at Buffalo, as well as first officer Shaw, but obviously in those last few moments ... the flight instruments were not being monitored, and that's an indication of a lack of situational awareness," said John Barrett, Colgan's director of flight standards.[58]

The official transcript of the crew's communication, obtained from the CVR, as well as an animated depiction of the crash, constructed using data from the FDR, were made available to the public on May 12, 2009. Some of the crew's communication violated federal rules banning nonessential conversation.[59] From May 12 to 14, the NTSB interviewed 20 witnesses of the flight.[60]

On June 3, 2009, the New York Times published an article[61] detailing complaints about Colgan's operations from an FAA inspector who observed test flights in January 2008. As in a previous FAA incident handling other inspectors' complaints,[61] the Colgan inspector's complaints were deferred and the inspector was demoted. The incident is under investigation by the Office of Special Counsel, the agency responsible for U.S. Government federal whistle-blower complaints.

Final report

On February 2, 2010, the NTSB issued its final report, describing its investigation, findings, conclusions and recommendations. The report includes a "Conclusions" section that summarizes the known facts and lists a variety of contributing factors relating to the flight crew. The probable cause was described as:

The captain’s inappropriate response to the activation of the stick shaker, which led to an aerodynamic stall from which the airplane did not recover.

[2]:155

The NTSB further added the following contributing factors:

Contributing to the accident were (1) the flight crew’s failure to monitor airspeed in relation to the rising position of the low-speed cue, (2) the flight crew’s failure to adhere to sterile cockpit procedures, (3) the captain’s failure to effectively manage the flight, and (4) Colgan Air’s inadequate procedures for airspeed selection and management during approaches in icing conditions.

However, the NTSB was unable to determine why the first officer retracted the flaps and suggested that the landing gear should be retracted. The method by which civil aircraft pilots can obtain their licenses was also criticized by the NTSB. It also found that: "The pilots' performance was likely impaired because of fatigue, but the extent of their impairment and the degree to which it contributed to the performance deficiencies that occurred during the flight cannot be conclusively determined."

NTSB Chair Deborah Hersman, while concurring, made it clear she considered fatigue a contributing factor. She compared the twenty years that fatigue has remained on the NTSB's Most wanted list of transportation safety improvements, without getting substantial action on the matter from regulators, to the changes in tolerance for alcohol over the same time period, noting that the performance impacts of fatigue and alcohol were similar.[2]:176–178

However, Christopher A. Hart and member Robert L. Sumwalt, III, dissented with the inclusion of fatigue as a contributing factor, on the grounds that there was not enough evidence to support such a conclusion. It was noted that the same kind of pilot errors and standard operating procedure violations had been found in other accidents where fatigue was not a factor.[2]:182–187

Legacy

The FAA has proposed or implemented several rule changes as a result of the Flight 3407 accident, in areas ranging from pilot fatigue to Airline Transport Pilot Certificate (ATP) qualifications of up to 1500 hours of flight experience prior to hiring. One of the most significant changes has already taken effect, changing the way examiners grade checkrides in flight simulators during stalls.[62]

Investigators also scrutinized the Practical Test Standards (PTS) for ATP certification, which allowed for an altitude loss of no more than 100 feet (30 m) in a simulated stall. The NTSB theorized that due to this low tolerance in a tested simulation environment, pilots may have come to fear loss of altitude in a stall and thus focused primarily on preventing such a loss, even to the detriment of recovering from the stall itself. New standards subsequently issued by the FAA eliminate any specific altitude loss stipulation, calling instead for "minimal loss of elevation" in a stall. One examiner has told an aviation magazine that he is not allowed to fail any applicant for losing altitude in a simulated stall, so long as the pilot is able to regain the original altitude.[62]

Dramatization

The story of the disaster was featured on the tenth season of Canadian National Geographic Channel show Mayday (known as Air Emergency in the US, Mayday in Ireland and France, and Air Crash Investigation in the UK and the rest of world) episode entitled "Dead Tired".

See also

- Atlantic Coast Airlines Flight 6291

- China Airlines Flight 140 – a similar accident caused by aerodynamic stall

- Icing conditions in aviation

References

- ↑ Update on NTSB investigation into crash of Colgan Air Dash-8 near Buffalo, New York NTSB advisory, March 25, 2009 "The data indicate a likely separation of the airflow over the wing and ensuing roll two seconds after the stick shaker activated while the aircraft was slowing through 125 knots and while at a flight load of 1.42 Gs. The predicted stall speed at a load factor of 1 G would be about 105 knots." Note: The predicted stall speed for this aircraft at a flight load of 1.42 Gs would be about 125 kts which is arrived at by multiplying 105 kts (the predicted stall speed at 1 G) by 1.19164 (the square root of the flight load in Gs).

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Accident report – Loss of control on approach Colgan Air, Inc. operating as Continental Connection Flight 3407 Bombardier DHC-8-400, N200WQ Clarence Center" (PDF). National Transportation Safety Board. February 12, 2009. Retrieved November 10, 2015.

- ↑ "Airline Safety and Federal Aviation Administration Extension Act of 2010". LegiScan. Retrieved October 26, 2014.

- ↑ name=ntsb/aar-10/01/

- ↑ "FAA Registry: N-Number Inquiry Results". Federal Aviation Administration. Retrieved November 10, 2015.

- ↑ Babineck, Mark; Hensel, Bill Jr. (February 13, 2009). "Records show Colgan flights had been fatality free". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved February 13, 2009.

- ↑ "Co-pilot of crashed plane was from Wash". KATU. February 13, 2009. Retrieved February 13, 2009.

- ↑ "Tahoma High grad Rebecca Shaw dies in Continental 3407 crash". Pacific Northwest Local News. February 14, 2009.

- ↑ "Maple Valley woman co-pilot in plane crash: Rebecca Shaw, 24, worked hard to join ranks of airlines". SeattlePI.com. February 13, 2009.

- ↑ "Frequently Asked Questions – Colgan Air Flight 3407" (PDF). Retrieved February 26, 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 "Victims of the crash of Flight 3407". Buffalo News. February 18, 2009. Archived from the original on February 18, 2009.

- ↑ "Commuter plane crashes into New York home". CBS News. February 12, 2009. Retrieved February 12, 2009.

- 1 2 3 "Search for answers begins in Buffalo plane crash". CNN. February 13, 2009. Retrieved February 13, 2009.

- ↑ "Obama extends sympathies to crash victims". UPI. February 12, 2009. Retrieved February 12, 2009.

- ↑ All calm moments before plane crashes (February 13, 2009). CBS News. Retrieved 2009-02-13.

- 1 2 Dale Anderson and Phil Fairbanks (February 12, 2009). "Federal investigators begin searching for the cause of Clarence Center crash". The Buffalo News.

- 1 2 Precious Yutangco (February 13, 2009). "49 killed after plane crashes into home near Buffalo". Toronto: Toronto Star.

- ↑ Transcript of CVR recording

- 1 2 3 4 "NTSB: Crew reported ice buildup before crash". MSNBC. February 12, 2009. Retrieved February 14, 2009.

- ↑ "NTSB: Colgan 3407 pitched up despite anti-stall push". Flight Global. February 15, 2009. Archived from the original on May 24, 2013. Retrieved February 16, 2009.

- ↑ George, Eli (February 26, 2014). "Flight 3407 crash site to become town property". wivb.com. WIVB-TV. Retrieved March 29, 2014.

- ↑ Residents survive after plane crashes through home. WBEN (AM) 930 Buffalo. February 13, 2009. Archived February 15, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Carey, Elizabeth (February 13, 2009). "Buffalo area plane crash claims 50 lives". The Business Review. Retrieved February 13, 2009.

- ↑ Karen Wielinski tells her story of survival after Flight 3407 crashed into her home February 13, 2009

- ↑ "Mom, daughter escape after plane crashes into home". cnn.com. February 13, 2009. Retrieved February 13, 2009.

- 1 2 3 "NTSB: Plane didn't dive, landed flat on house". MSNBC. February 14, 2009. Retrieved February 14, 2009.

- ↑ "50 killed as US plane crashes into house". Dawn. February 14, 2009. Archived from the original on February 19, 2009.

- ↑ "Fiery plane crash in upstate N.Y. kills 50". NPR. February 13, 2009.

- ↑ Dolmetsch, Chris; Miller, Hugo (February 13, 2009). "Continental flight crashes near Buffalo, killing 50" (Update3 ed.). Bloomberg. Retrieved November 10, 2015.

- ↑ Tapper, Jake; Travers, Karen (February 13, 2009). "President Obama mentions plane crash, and victim Beverly Eckert". Retrieved February 13, 2009.

- ↑ Newberg, Rich (February 19, 2009). "Community says goodbye to Susan Wehle". WIVB. Retrieved May 27, 2013.

- ↑ "Colgan Air, Inc. releases additional information regarding Flight 3407" (PDF). Colgan Air. February 13, 2009. Retrieved February 13, 2009.

- ↑ "Senior Services". Town of Cheektowaga. Archived from the original on September 26, 2006. Retrieved May 25, 2009.

- ↑ "Cheektowaga CDP, New York". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on June 2, 2009. Retrieved May 25, 2009.

- ↑ "Red Cross provides comfort and counseling to families of Buffalo plane crash". American Red Cross. Retrieved February 13, 2009.

- ↑ "Local leaders react in wake of Flight 3407 crash". WCBSTV (via Archive.Org). February 13, 2009. Archived from the original on May 20, 2009. Retrieved February 13, 2009.

- ↑ Hunter, Brian (February 14, 2009). "Sabres gut out emotional win". NHL. Retrieved February 14, 2009.

- ↑ "11 with UB ties die in plane crash". University at Buffalo: UB Reporter. February 13, 2009. Retrieved February 18, 2009.

- ↑ "UB remembers victims of plane crash". University at Buffalo: UB Reporter. February 18, 2009. Retrieved February 18, 2009.

- ↑ "A Message from President Howard about the Tragedy of Flight 3407". Buffalo State College. February 19, 2009. Retrieved February 25, 2009.

- ↑ "Paterson plans Flight 3407 scholarships". University at Buffalo: UB Reporter. March 4, 2009. Retrieved March 4, 2009.

- ↑ Genzlinger, Neil (February 8, 2010). "Up in the air, with frayed safety nets". The New York Times. Retrieved May 20, 2015.

- ↑ "Flying Cheap". PBS. February 9, 2010. Retrieved April 10, 2010. The full transcript of the episode is available here on PBS

- ↑ Wawrow, John (February 13, 2009). "Fiery plane crash in upstate NY kills 50". Yahoo!. Archived from the original on February 16, 2009. Retrieved February 13, 2009.

- ↑ "Black Boxes Found From Buffalo Crash". cbsnews.com. February 13, 2009. Retrieved February 13, 2009.

- 1 2 "NTSB: Plane rolled violently before crash". CNN. February 15, 2009. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- ↑ "NTSB: Crew saw ice buildup before crash". CBS News. February 13, 2009. Retrieved February 13, 2009.

- ↑ "Strong sense of purpose drives investigators". The Buffalo News. February 15, 2009. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- ↑ "Crash plane 'dropped in seconds'". BBC News. February 15, 2009. Retrieved February 16, 2009.

- ↑ "Americas | Fatal US plane 'was on autopilot'". BBC News. February 16, 2009. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- ↑ "Plane that crashed near Buffalo was on autopilot". The Washington Post. February 15, 2009. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- ↑ Pasztor, Andy (February 15, 2009). "Flight was on autopilot; anti-ice systems apparently working". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- ↑ Wald, Matthew L. (February 18, 2009). "In recreating Flight 3407, a hint of human error". New York Times. Retrieved February 18, 2009.

- ↑ Alan Levin (February 15, 2009). "NTSB: Plane landed on its belly, facing away from airport". USA Today. Retrieved February 22, 2009.

- 1 2 Andy Pasztor (May 11, 2009). "Captain's training faulted in air crash that killed 50". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved June 2, 2015. (subscription required (help)).

Before joining Colgan, he failed three proficiency checks on general aviation aircraft administered by the FAA, according to investigators and the airline

- ↑ "Public Hearing – May 12–14, 2009". National Transportation Safety Board. Retrieved June 2, 2013.

13:30 – 15:30 Witnesses #18, #19, #20: Regulator Policy and Guidance

- ↑ Frances Fiorino (September 25, 2009). "House hearing reviews efforts to improve safety". Aviation Week and Space Technology. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "Inquiry in New York air crash points to crew error". Los Angeles Times. May 13, 2009.

- ↑ Matthew L. Wald (May 13, 2009). "Pilots chatted in moments before Buffalo crash". New York Times;. Retrieved May 23, 2009.

- ↑ "Public Hearing – May 12–14, 2009". National Transportation Safety Board. Retrieved June 2, 2013.

13:30 – 15:30 Witnesses #18, #19, #20: Regulator Policy and Guidance

- 1 2 Matthew L. Wald (June 3, 2009). "Inspector predicted problems a year before Buffalo crash". New York Times. Retrieved June 3, 2009.

- 1 2 Goyer, Robert (July 2011). "To Push or to Pull". Flying. Bonnier Corporation. 138 (7): 8–9. Retrieved July 4, 2011.

External links

| Wikinews has the following articles detailing the reaction at the time to the crash of Flight 3407: | |

- Cockpit Voice Recorder transcript and accident summary

- Flight 3407 Information – Colgan Air (Archive)

- Website created and maintained by family members and close friends of victims who perished onboard flight 3407

- NTSB Computer simulation of last 2 minutes of flight 3407, National Transportation Safety Board

- NTSB Public hearing, May 12–14, 2009. (Includes webcast of complete hearing and link to docket with all relevant documents, including Flight Data Recorder data and Cockpit Voice Recorder transcript)

- Flight path for CJC3407 in 3D/Google Earth at flightwise.com

- Flight track data for Continental Connection flight 3407 at flightwise.com

- Information Regarding Flight 3407 – Continental Airlines

- Flight tracker and Track log

- Flickr photo set of the crash

- A picture of the aircraft taken in late 2008.

- After Sept. 11, 'He Wanted Me To Live A Full Life' (about victim Beverly Eckert) from NPR radio

- Buffalo Crash Puts Focus On Regional Airlines from NPR radio

- Frontline (U.S. TV series) – Flying Cheap – February 9, 2010. One year after the deadly crash of Continental 3407, FRONTLINE investigate the safety issues associated with regional airlines.

- Track log for Continental Connection flight 3407 (CJC3407) at flightwise.com

Coordinates: 43°00′42″N 78°38′21″W / 43.011602°N 78.63904°W