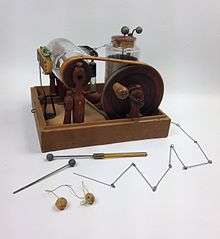

Corbett's electrostatic machine

Corbett's electrostatic machine is a high voltage static electricity generating device that was used by Shaker doctors for medical treatment in the early nineteenth century. Corbett's machine is in the collection of the Mount Lebanon Shaker Village in the state of New York USA.

Thomas Corbett

This electrostatic machine was made by a Shaker pharmacist named Thomas Corbett in 1810 for medical treatment.[1] Corbett was the first physician botanist for the Shakers and was known for his herbal medicines and unorthodox medical "cures".[2]

Description

Corbett's electrostatic machine consists of a 0.5 inches (13 mm) wooden base platform sitting on a 2-inch (51 mm) frame, forming a box. The wooden platform is about 12 inches (300 mm) wide and about 9 inches (230 mm) deep. To one side of the wooden platform is mounted a small axle on pivots, which holds a rotating glass jar cylinder about the size of a Mason jar. This glass jar is attached to a crank wheel of about 5 inches (130 mm) with a leather belt. The crank wheel can be turned by hand. The wooden platform also contains a Leyden jar-style battery in one corner, standing some 9 inches (230 mm) high. The Leyden jar is a glass receptacle with a metal rod in the center, covered by a metal ball on top which collects and releases a high voltage electrical charge.[3]

Operation

The crank wheel of Corbett's electrostatic machine was turned by an operator using the knob handle; the glass cylinder was rotated by an attached belt. The glass jar rubbed against a layered silk cloth pad or a textile cloth pad, developing a high voltage positive electrical charge.[4] This static electricity charge was taken off the glass cylinder through a small metal rake and transferred by wire to the Leyden jar storage battery for later use (see close-up illustration).[3] The high voltage stored electrostatic charge kept in the Leyden jar was on the metal ball on top of the high voltage storage battery. It would produce a spark visible to the eye when the set of small metal globes attached to the battery were brought close enough to each other as a test experiment in a discharge.[5]

Treatment technique

The high voltage static charge on top of the Leyden jar storage battery was applied to a patient as he or she sat on a chair or stool atop a special platform. The four glass legs of the chair insulated the platform from the ground. The operator channeled the stored charge from the Leyden jar to the patient using metal attachments that were connected to the patient. The electrical charge produced a shock that was similar to "touching a doorknob after walking across carpet in dry weather".[3]

The electrical treatment from Corbett's electrostatic machine supposedly "cured" the sufferer of a variety of illnesses, or at least had some electrotherapeutic value.[6] It was especially designed to treat rheumatism.[6] More likely, however, the electrical shock temporarily diverted the sufferer's mind from his or her aches and pains.[7] Shaker Elizabeth Lovegrove recorded in a journal of 1837 that an Elder Sister was being treated by the Corbett machine. She reported that she felt better after each treatment, at least temporarily.[7]

Electrical principles

Corbett's experiments with electricity and its principles shows his interest in science and medicine.[8] The electrostatic machine and his electrical experiments in the early 1800s took place between Benjamin Franklin's electrical experiments of the mid-1700s and that of Thomas Edison's electrical inventions.[5] The electrical principles of Corbett's electrostatic machine were later used by Edison.[9]

See also

References

Citations

- ↑ Inventions of theShakers, Popular Mechanics, 1976

- ↑ Swank 1999, p. 82.

- 1 2 3 Sharon Duane Koomler (2015). "Thomas Corbett electrostatic machine". Seeking Perfect - the Shaker's material world. Antiques and Fine Art.

- ↑ "Franklin-Wistar Friction Machine". Niagara Science Museum. 2015.

- 1 2 Williams 1971, p. 31.

- 1 2 Cohen 1998, p. 98.

- 1 2 Sprigg 1990, p. 121.

- ↑ Miller 1999, p. 45.

- ↑ Shea 1992, p. 22.

Sources

- Cohen, Brenda H. (1998). America's Scientific Treasures: A Travel Companion. American Chemical Society. ISBN 0841234442.

- Miller, Amy Bess Williams (1999). Shaker Medicinal Herbs: A Compendium of History, Lore, and Uses. Storey Books. ISBN 1580170404.

- Shea, John Gerald (1992). Making Authentic Shaker Furniture: With Measured Drawings of Museum Classics. Courier Corporation. ISBN 0486270033.

While believed to have electrotherapeutic value, it proved principles later applied by Thomas Edison.

- Sprigg, June (1990). By Shaker Hands: The Art and the World of the Shakers. University Press of New England.

- Swank, Scott T. (1999). Shaker Life, Art, and Architecture: Hands to Work, Hearts to God. Abbeville Press. ISBN 0789203588.

- Williams, John S. (1971), The Shaker Museum, Shaker Museum Foundation