Malcolm III of Scotland

| Malcolm III | |

|---|---|

|

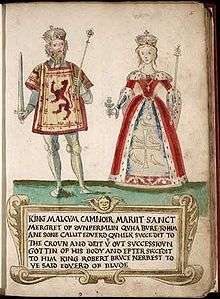

Victorian depiction of Malcolm and his second wife, Margaret | |

| King of Alba | |

| Reign | 1058–1093 |

| Coronation | 25 April 1058?, Scone |

| Predecessor | Lulach |

| Successor | Donald III |

| Born |

c. 1031 Scotland |

| Died |

13 November 1093 Alnwick, Northumberland, England |

| Burial | Tynemouth |

| Spouse |

Ingibiorg Finnsdottir Margaret of Wessex |

| Issue |

Duncan II, King of Scots Edward, Prince of Scotland Edmund Ethelred Edgar, King of Scots Alexander, King of Scots David I, King of Scots Edith, Queen of England Mary, Countess of Boulogne |

| House | House of Dunkeld |

| Father | Duncan I |

| Mother | Suthen |

Malcolm (Gaelic: Máel Coluim; c. 26 March 1031 – 13 November 1093) was King of Scots from 1058 to 1093. He was later nicknamed Canmore (ceann mòr) in Scottish Gaelic, "Great Chief". (Ceann = leader, "head" [of state]. Mòr = pre-eminent, great, "big".) [1][2] Malcolm's long reign, lasting 35 years, preceded the beginning of the Scoto-Norman age. He is the historical equivalent of the character of the same name in Shakespeare's Macbeth.

Malcolm's kingdom did not extend over the full territory of modern Scotland: the north and west of Scotland remained in Scandinavian, Norse-Gael and Gaelic control, and the areas under the control of the Kings of Scots did not advance much beyond the limits set by Malcolm II until the 12th century. Malcolm III fought a succession of wars against the Kingdom of England, which may have had as their goal the conquest of the English earldom of Northumbria. These wars did not result in any significant advances southwards. Malcolm's main achievement is to have continued a line which would rule Scotland for many years,[3] although his role as "founder of a dynasty" has more to do with the propaganda of his youngest son David, and his descendants, than with any historical reality.[4]

Malcolm's second wife, Margaret of Wessex, was eventually canonized and is Scotland's only royal saint. Malcolm himself gained no reputation for piety; with the notable exception of Dunfermline Abbey, he is not definitely associated with major religious establishments or ecclesiastical reforms.

Background

Malcolm's father Duncan I became king in late 1034, on the death of Malcolm II, Duncan's maternal grandfather and Malcolm's great-grandfather. According to John of Fordun, whose account is the original source of part at least of William Shakespeare's Macbeth, Malcolm's mother was a niece of Siward, Earl of Northumbria,[5][6] but an earlier king-list gives her the Gaelic name Suthen.[7] Other sources claim that either a daughter or niece would have been too young to fit the timeline, thus the likely relative would have been Siward's own sister Sybil, which may have translated into Gaelic as Suthen.

Duncan's reign was not successful and he was killed by Macbeth on 15 August 1040. Although Shakespeare's Macbeth presents Malcolm as a grown man and his father as an old one, it appears that Duncan was still young in 1040,[8] and Malcolm and his brother Donalbane were children.[9] Malcolm's family did attempt to overthrow Macbeth in 1045, but Malcolm's grandfather Crínán of Dunkeld was killed in the attempt.[10]

Soon after the death of Duncan his two young sons were sent away for greater safety—exactly where is the subject of debate. According to one version, Malcolm (then aged about nine) was sent to England,[11] and his younger brother Donalbane was sent to the Isles.[12][13] Based on Fordun's account, it was assumed that Malcolm passed most of Macbeth's seventeen-year reign in the Kingdom of England at the court of Edward the Confessor.[14][15]

According to an alternative version, Malcolm's mother took both sons into exile at the court of Thorfinn Sigurdsson, Earl of Orkney, an enemy of Macbeth's family, and perhaps Duncan's kinsman by marriage.[16]

An English invasion in 1054, with Siward, Earl of Northumbria in command, had as its goal the installation of one "Máel Coluim, son of the King of the Cumbrians". This Máel Coluim has traditionally been identified with the later Malcolm III.[17] This interpretation derives from the Chronicle attributed to the 14th-century chronicler of Scotland, John of Fordun, as well as from earlier sources such as William of Malmesbury.[18] The latter reported that Macbeth was killed in the battle by Siward, but it is known that Macbeth outlived Siward by two years.[19] A. A. M. Duncan argued in 2002 that, using the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle entry as their source, later writers innocently misidentified "Máel Coluim" with the later Scottish king of the same name.[20] Duncan's argument has been supported by several subsequent historians specialising in the era, such as Richard Oram, Dauvit Broun and Alex Woolf.[21] It has also been suggested that Máel Coluim may have been a son of Owen the Bald, British king of Strathclyde[22] perhaps by a daughter of Malcolm II, King of Scotland.[23]

In 1057 various chroniclers report the death of Macbeth at Malcolm's hand, on 15 August 1057 at Lumphanan in Aberdeenshire.[24][25] Macbeth was succeeded by his stepson Lulach, who was crowned at Scone, probably on 8 September 1057. Lulach was killed by Malcolm, "by treachery",[26] near Huntly on 23 April 1058. After this, Malcolm became king, perhaps being inaugurated on 25 April 1058, although only John of Fordun reports this.[27]

Malcolm and Ingibiorg

If Orderic Vitalis is to be relied upon, one of Malcolm's earliest actions as king may have been to travel south to the court of Edward the Confessor in 1059 to arrange a marriage with Edward's kinswoman Margaret, who had arrived in England two years before from Hungary.[28] If he did visit the English court, he was the first reigning king of Scots to do so in more than eighty years. If a marriage agreement was made in 1059, it was not kept, and this may explain the Scots invasion of Northumbria in 1061 when Lindisfarne was plundered.[29] Equally, Malcolm's raids in Northumbria may have been related to the disputed "Kingdom of the Cumbrians", reestablished by Earl Siward in 1054, which was under Malcolm's control by 1070.[30]

The Orkneyinga saga reports that Malcolm married the widow of Thorfinn Sigurdsson, Ingibiorg, a daughter of Finn Arnesson.[31] Although Ingibiorg is generally assumed to have died shortly before 1070, it is possible that she died much earlier, around 1058.[32] The Orkneyinga Saga records that Malcolm and Ingibiorg had a son, Duncan II (Donnchad mac Maíl Coluim), who was later king.[33] Some Medieval commentators, following William of Malmesbury, claimed that Duncan was illegitimate, but this claim is propaganda reflecting the need of Malcolm's descendants by Margaret to undermine the claims of Duncan's descendants, the Meic Uilleim.[34] Malcolm's son Domnall, whose death is reported in 1085, is not mentioned by the author of the Orkneyinga Saga. He is assumed to have been born to Ingibiorg.[35]

Malcolm's marriage to Ingibiorg secured him peace in the north and west. The Heimskringla tells that her father Finn had been an adviser to Harald Hardraade and, after falling out with Harald, was then made an Earl by Sweyn Estridsson, King of Denmark, which may have been another recommendation for the match.[36] Malcolm enjoyed a peaceful relationship with the Earldom of Orkney, ruled jointly by his stepsons, Paul and Erlend Thorfinnsson. The Orkneyinga Saga reports strife with Norway but this is probably misplaced as it associates this with Magnus Barefoot, who became king of Norway only in 1093, the year of Malcolm's death.[37]

Malcolm and Margaret

Although he had given sanctuary to Tostig Godwinson when the Northumbrians drove him out, Malcolm was not directly involved in the ill-fated invasion of England by Harald Hardraade and Tostig in 1066, which ended in defeat and death at the battle of Stamford Bridge.[38] In 1068, he granted asylum to a group of English exiles fleeing from William of Normandy, among them Agatha, widow of Edward the Confessor's nephew Edward the Exile, and her children: Edgar Ætheling and his sisters Margaret and Cristina. They were accompanied by Gospatric, Earl of Northumbria. The exiles were disappointed, however, if they had expected immediate assistance from the Scots.[39]

In 1069 the exiles returned to England, to join a spreading revolt in the north. Even though Gospatric and Siward's son Waltheof submitted by the end of the year, the arrival of a Danish army under Sweyn Estridsson seemed to ensure that William's position remained weak. Malcolm decided on war, and took his army south into Cumbria and across the Pennines, wasting Teesdale and Cleveland then marching north, loaded with loot, to Wearmouth. There Malcolm met Edgar and his family, who were invited to return with him, but did not. As Sweyn had by now been bought off with a large Danegeld, Malcolm took his army home. In reprisal, William sent Gospatric to raid Scotland through Cumbria. In return, the Scots fleet raided the Northumbrian coast where Gospatric's possessions were concentrated.[40] Late in the year, perhaps shipwrecked on their way to a European exile, Edgar and his family again arrived in Scotland, this time to remain. By the end of 1070, Malcolm had married Edgar's sister Margaret of Wessex, the future Saint Margaret of Scotland.[41]

The naming of their children represented a break with the traditional Scots regal names such as Malcolm, Cináed and Áed. The point of naming Margaret's sons—Edward after her father Edward the Exile, Edmund for her grandfather Edmund Ironside, Ethelred for her great-grandfather Ethelred the Unready and Edgar for her great-great-grandfather Edgar and her brother, briefly the elected king, Edgar Ætheling—was unlikely to be missed in England, where William of Normandy's grasp on power was far from secure.[42] Whether the adoption of the classical Alexander for the future Alexander I of Scotland (either for Pope Alexander II or for Alexander the Great) and the biblical David for the future David I of Scotland represented a recognition that William of Normandy would not be easily removed, or was due to the repetition of Anglo-Saxon royal name—another Edmund had preceded Edgar—is not known.[43] Margaret also gave Malcolm two daughters, Edith, who married Henry I of England, and Mary, who married Eustace III of Boulogne.

In 1072, with the Harrying of the North completed and his position again secure, William of Normandy came north with an army and a fleet. Malcolm met William at Abernethy and, in the words of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle "became his man" and handed over his eldest son Duncan as a hostage and arranged peace between William and Edgar.[44] Accepting the overlordship of the king of the English was no novelty, as previous kings had done so without result. The same was true of Malcolm; his agreement with the English king was followed by further raids into Northumbria, which led to further trouble in the earldom and the killing of Bishop William Walcher at Gateshead. In 1080, William sent his son Robert Curthose north with an army while his brother Odo punished the Northumbrians. Malcolm again made peace, and this time kept it for over a decade.[45]

Malcolm faced little recorded internal opposition, with the exception of Lulach's son Máel Snechtai. In an unusual entry, for the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle contains little on Scotland, it says that in 1078:

Malcholom [Máel Coluim] seized the mother of Mælslæhtan [Máel Snechtai] ... and all his treasures, and his cattle; and he himself escaped with difficulty.[46]

Whatever provoked this strife, Máel Snechtai survived until 1085.[47]

Malcolm and William Rufus

When William Rufus became king of England after his father's death, Malcolm did not intervene in the rebellions by supporters of Robert Curthose which followed. In 1091, William Rufus confiscated Edgar Ætheling's lands in England, and Edgar fled north to Scotland. In May, Malcolm marched south, not to raid and take slaves and plunder, but to besiege Newcastle, built by Robert Curthose in 1080. This appears to have been an attempt to advance the frontier south from the River Tweed to the River Tees. The threat was enough to bring the English king back from Normandy, where he had been fighting Robert Curthose. In September, learning of William Rufus's approaching army, Malcolm withdrew north and the English followed. Unlike in 1072, Malcolm was prepared to fight, but a peace was arranged by Edgar Ætheling and Robert Curthose whereby Malcolm again acknowledged the overlordship of the English king.[48]

In 1092, the peace began to break down. Based on the idea that the Scots controlled much of modern Cumbria, it had been supposed that William Rufus's new castle at Carlisle and his settlement of English peasants in the surrounds was the cause. It is unlikely that Malcolm controlled Cumbria, and the dispute instead concerned the estates granted to Malcolm by William Rufus's father in 1072 for his maintenance when visiting England. Malcolm sent messengers to discuss the question and William Rufus agreed to a meeting. Malcolm travelled south to Gloucester, stopping at Wilton Abbey to visit his daughter Edith and sister-in-law Cristina. Malcolm arrived there on 24 August 1093 to find that William Rufus refused to negotiate, insisting that the dispute be judged by the English barons. This Malcolm refused to accept, and returned immediately to Scotland.[49]

It does not appear that William Rufus intended to provoke a war,[50] but, as the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle reports, war came:

For this reason therefore they parted with great dissatisfaction, and the King Malcolm returned to Scotland. And soon after he came home, he gathered his army, and came harrowing into England with more hostility than behoved him ....[51]

Malcolm was accompanied by Edward, his eldest son by Margaret and probable heir-designate (or tánaiste), and by Edgar.[52] Even by the standards of the time, the ravaging of Northumbria by the Scots was seen as harsh.[53]

Death

While marching north again, Malcolm was ambushed by Robert de Mowbray, Earl of Northumbria, whose lands he had devastated, near Alnwick on 13 November 1093. There he was killed by Arkil Morel, steward of Bamburgh Castle. The conflict became known as the Battle of Alnwick.[54] Edward was mortally wounded in the same fight. Margaret, it is said, died soon after receiving the news of their deaths from Edgar.[55] The Annals of Ulster say:

Mael Coluim son of Donnchad, over-king of Scotland, and Edward his son, were killed by the French [i.e. Normans] in Inber Alda in England. His queen, Margaret, moreover, died of sorrow for him within nine days.[56]

Malcolm's body was taken to Tynemouth Priory for burial. The king's body was sent north for reburial, in the reign of his son Alexander, at Dunfermline Abbey, or possibly Iona.[57]

On 19 June 1250, following the canonisation of Malcolm's wife Margaret by Pope Innocent IV, Margaret's remains were disinterred and placed in a reliquary. Tradition has it that as the reliquary was carried to the high altar of Dunfermline Abbey, past Malcolm's grave, it became too heavy to move. As a result, Malcolm's remains were also disinterred, and buried next to Margaret beside the altar.[58]

Issue

Malcolm and Ingibiorg had three sons:

- Duncan II of Scotland, succeeded his father as King of Scotland

- Donald, died ca.1094

- Malcolm, died ca.1085

Malcolm and Margaret had eight children, six sons and two daughters:

- Edward, killed 1093

- Edmund of Scotland

- Ethelred, abbot of Dunkeld

- King Edgar of Scotland

- King Alexander I of Scotland

- King David I of Scotland

- Edith of Scotland, also called Matilda, married King Henry I of England

- Mary of Scotland, married Eustace III of Boulogne

Depictions in fiction

Malcolm appears in William Shakespeare’s Macbeth as Malcolm, and also as the anti-hero of its 2009-written (by Noah Lukeman), and historically very inaccurate, successor-play The Tragedy of Macbeth Part II. He is the son of King Duncan and heir to the throne. He first appears in the second scene where he is talking to a sergeant, with Duncan. The sergeant tells them how the battle was won thanks to Macbeth. Then Ross comes and Duncan decides that Macbeth should take the title of Thane of Cawdor. Then he later appears in Act 1.4 talking about the execution of the former Thane of Cawdor. Macbeth then enters and they congratulate him on his victory. He later appears in Macbeth’s castle as a guest. When his father is killed he is suspected of the murder so he escapes to England. He later makes an appearance in Act 4.3, where he talks to Macduff about Macbeth and what to do. They both decide to start a war against him. In Act 5.4 he is seen in Dunsinane getting ready for war. He orders the troops to hide behind branches and slowly advance towards the castle. In Act 5.8 he watches the battle against Macbeth and Macduff with Siward and Ross. When eventually Macbeth is killed, Malcolm takes over as king.

The married life of Malcolm III and Margaret has been the subject of two historical novels: A Goodly Pearl (1905) by Mary H. Debenham, and Malcolm Canmore's Pearl (1907) by Agnes Grant Hay. Both focus on court life in Dunfermline, and the Margaret helping introduce Anglo-Saxon culture in Scotland. The latter novel covers events to 1093, ending with Malcolm's death.[59][60]

Canmore appears in the third and fourth episodes of the four-part series "City of Stone" in Disney's Gargoyles, as an antagonist of Macbeth. After witnessing his father Duncan's death, the young Canmore swears revenge on both Macbeth and his gargoyle ally, Demona. After reaching adulthood, he overthrows Macbeth with English allies. Canmore is also the ancestor of the Hunters, a family of vigilantes who hunt Demona through the centuries. Canmore was voiced in the series by J.D. Daniels as a boy and Neil Dickson as an adult.

In The Tragedy of Macbeth Part II, Malcolm (who has succeeded from MacBeth, and ruled well for ten years) is led by the witches down MacBeth's path to perdition -- killing his brother Donalbain as well as MacDuff before finally being killed by Fleance (supposedly the ancestor of Stuart king James).

Ancestry

| 4. Crínán of Dunkeld | ||||||||||||||||

| 2. Duncan I, King of Scots | ||||||||||||||||

| 20. Kenneth II, King of Scots | ||||||||||||||||

| 10. Malcolm II, King of Scots | ||||||||||||||||

| 5. Bethóc | ||||||||||||||||

| 1. Malcolm III, King of Scots | ||||||||||||||||

| 3. Suthen | ||||||||||||||||

Notes

- ↑ Magnusson, p. 61

- ↑ Burton, vol. 1, p. 350, states: "Malcolm the son of Duncan is known as Malcolm III., but still better perhaps by his characteristic name of Canmore, said to come from the Celtic 'Cenn Mór', meaning 'great head'". It has also been argued recently that the real "Malcolm Canmore" was this Malcolm's great-grandson Malcolm IV, who is given this name in the contemporary notice of his death. Duncan, pp. 51–52, 74–75; Oram, p. 17, note 1.

- ↑ The question of what to call this family is an open one. "House of Dunkeld" is all but unknown; "Canmore kings" and "Canmore dynasty" are not universally accepted, nor are Richard Oram's recent coinage "meic Maíl Coluim" or Michael Lynch's "MacMalcolm". For discussions and examples: Duncan, pp. 53–54; McDonald, Outlaws, p. 3; Barrow, Kingship and Unity, Appendix C; Reid. Broun discusses the question of identity at length.

- ↑ Hammond, p. 21. The first genealogy known which traces descent from Malcolm, rather than from Kenneth MacAlpin (Cináed mac Ailpín) or Fergus Mór, is dated to the reign of Alexander II, see Broun, pp. 195–200.

- ↑ Fordun, IV, xliv.

- ↑ Young also gives her as a niece of Siward. Young, p. 30.

- ↑ Duncan, p. 37; M.O. Anderson, p. 284.

- ↑ The notice of Duncan's death in the Annals of Tigernach, s.a. 1040, says he was "slain ... at an immature age"; Duncan, p.33.

- ↑ Duncan, p. 33; Oram, David I, p. 18. There may have been a third brother if Máel Muire of Atholl was a son of Duncan. Oram, David I, p. 97, note 26, rejects this identification.

- ↑ Duncan, p. 41; Annals of Ulster, s.a. 1045 ; Annals of Tigernach, s.a. 1045.

- ↑ Annals of Scotland, Volume 1, By Sir David Dalrymple, Page32

- ↑ Ritchie, p.3

- ↑ Young, p.30

- ↑ Barrell, p. 13; Barrow, Kingship and Unity, p. 25.

- ↑ Ritchie, p.3, states that it was fourteen years of exile, partly spent at Edward's Court.

- ↑ Duncan, p. 42; Oram, David I, pp. 18–20. Malcolm had ties to Orkney in later life. Earl Thorfinn may have been a grandson of Malcolm II and thus Malcolm's cousin.

- ↑ See, for instance, Ritchie, Normans, p. 5, or Stenton, Anglo-Saxon England, p. 570. Ritchie, p. 5, states that Duncan placed his son, the future Malcolm III of Scotland, in possession of Cumbria as its Prince, and states that Siward invaded Scotland in 1054 to restore him to the Scottish throne. Hector Boece also says this (vol.XII p.249), as does Young, p. 30.

- ↑ Broun, "Identity of the Kingdom", pp. 133–34; Duncan, Kingship, p. 40

- ↑ Oram, David I, p. 29

- ↑ Duncan, Kingship, pp. 37–41

- ↑ Broun, "Identity of the Kingdom", p. 134; Oram, David I, pp. 18–20; Woolf, Pictland to Alba, p. 262

- ↑ Duncan, Kingship of the Scots, p. 41

- ↑ Woolf, Pictland to Alba, p. 262

- ↑ Ritchie, p. 7

- ↑ Anderson, ESSH, pp. 600–602; the Prophecy of Berchán has Macbeth wounded in battle and places his death at Scone.

- ↑ According to the Annals of Tigernach; the Annals of Ulster say Lulach was killed in battle against Malcolm; see Anderson, ESSH, pp. 603–604.

- ↑ Duncan, pp. 50–51 discusses the dating of these events.

- ↑ Duncan, p. 43; Ritchie, pp. 7–8.

- ↑ Duncan, p. 43; Oram, David I, p. 21.

- ↑ Oram, David I, p. 21.

- ↑ Orkneyinga Saga, c. 33, Duncan, pp. 42–43.

- ↑ See Duncan, pp. 42–43, dating Ingibiorg's death to 1058. Oram, David I, pp. 22–23, dates the marriage of Malcolm and Ingibiorg to c. 1065.

- ↑ Orkneyinga Saga, c. 33.

- ↑ Duncan, pp. 54–55; Broun, p. 196; Anderson, SAEC, pp. 117–119.

- ↑ Duncan, p. 55; Oram, David I, p. 23. Domnall's death is reported in the Annals of Ulster, s.a. 1085: "... Domnall son of Máel Coluim, king of Alba, ... ended [his] life unhappily." However, it is not certain that Domnall's father was this Máel Coluim. M.O. Anderson, ESSH, corrigenda p. xxi, presumes Domnall to have been a son of Máel Coluim mac Maíl Brigti, King or Mormaer of Moray, who is called "king of Scotland" in his obituary in 1029.

- ↑ Saga of Harald Sigurðson, cc. 45ff.; Saga of Magnus Erlingsson, c. 30. See also Oram, David I, pp. 22–23.

- ↑ Orkneyinga Saga, cc. 39–41; McDonald, Kingdom of the Isles, pp. 34–37.

- ↑ Adam of Bremen says that he fought at Stamford Bridge, but he is alone in claiming this: Anderson, SAEC, p. 87, n. 3.

- ↑ Oram, David I, p. 23; Anderson, SAEC, pp. 87–90. Orderic Vitalis states that the English asked for Malcolm's assistance.

- ↑ Duncan, pp. 44–45; Oram, David I, pp. 23–24.

- ↑ Oram, David I, p. 24; Clancy, "St. Margaret", dates the marriage to 1072.

- ↑ Malcolm's sons by Ingebiorg were probably expected to succeed to the kingdom of the Scots, Oram, David I, p. 26.

- ↑ Oram, p. 26.

- ↑ Oram, pp. 30–31; Anderson, SAEC, p. 95.

- ↑ Oram, David I, p. 33.

- ↑ Anderson, SAEC, p. 100.

- ↑ His death is reported by the Annals of Ulster amongst clerics and described as "happy", usually a sign that the deceased had entered religion.

- ↑ Oram, David I, pp. 34–35; Anderson, SAEC, pp. 104–108.

- ↑ Duncan, pp. 47–48; Oram, David I, pp. 35–36; Anderson, SAEC, pp. 109–110.

- ↑ Oram, David I, pp.36–37.

- ↑ 1093 The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle.

- ↑ Duncan, p. 54; Oram, David I, p. 42.

- ↑ Anderson, SAEC, pp. 97–113, contains a number of English chronicles condemning Malcolm's several invasions of Northumbria.

- ↑ The Annals of Innisfallen say he "was slain with his son in an unguarded moment in battle".

- ↑ Oram, pp. 37–38; Anderson, SAEC, pp. 114–115.

- ↑ The notice in the Annals of Innisfallen ends "and Margaréta his wife, died of grief for him."

- ↑ Anderson, SAEC, pp. 111–113. M.O. Anderson reprints three regnal lists, lists F, I and K, which give a place of burial for Malcolm. These say Iona, Dunfermline, and Tynemouth, respectively.

- ↑ Dunlop, p. 93.

- ↑ Baker (1914), p. 12-

- ↑ Nield (1925), p. 27

References

- Anderson, Alan Orr, Early Sources of Scottish History A.D 500–1286, volume 1. Reprinted with corrections. Paul Watkins, Stamford, 1990. ISBN 1-871615-03-8

- Anderson, Alan Orr, Scottish Annals from English Chroniclers. D. Nutt, London, 1908.

- Anderson, Marjorie Ogilvie, Kings and Kingship in Early Scotland. Scottish Academic Press, Edinburgh, revised edition 1980. ISBN 0-7011-1604-8

- Anon., Orkneyinga Saga: The History of the Earls of Orkney, tr. Hermann Pálsson and Paul Edwards. Penguin, London, 1978. ISBN 0-14-044383-5

- Baker, Ernest Albert (1914), A Guide to Historical Fiction, George Routledge and sons

- Barrell, A.D.M. Medieval Scotland. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2000. ISBN 0-521-58602-X

- Barrow, G.W.S., Kingship and Unity: Scotland, 1000–1306. Reprinted, Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh, 1989. ISBN 0-7486-0104-X

- Barrow, G.W.S., The Kingdom of the Scots. Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh, 2003. ISBN 0-7486-1803-1

- Broun, Dauvit, The Irish Identity of the Kingdom of the Scots in the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries. Boydell, Woodbridge, 1999. ISBN 0-85115-375-5

- Burton, John Hill, The History of Scotland, New Edition, 8 vols, Edinburgh 1876

- Clancy, Thomas Owen, "St. Margaret" in Michael Lynch (ed.), The Oxford Companion to Scottish History. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2002. ISBN 0-19-211696-7

- Duncan, A.A.M., The Kingship of the Scots 842–1292: Succession and Independence. Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh, 2002. ISBN 0-7486-1626-8

- Dunlop, Eileen, Queen Margaret of Scotland. National Museums of Scotland, Edinburgh, 2005. ISBN 1-901663-92-2

- Hammond, Matthew H., "Ethnicity and Writing of Medieval Scottish History", in The Scottish Historical Review, Vol. 85, April, 2006, pp. 1–27

- John of Fordun, Chronicle of the Scottish Nation, ed. William Forbes Skene, tr. Felix J.H. Skene, 2 vols. Reprinted, Llanerch Press, Lampeter, 1993. ISBN 1-897853-05-X

- McDonald, R. Andrew, The Kingdom of the Isles: Scotland's Western Seaboard, c. 1100–c.1336. Tuckwell Press, East Linton, 1997. ISBN 1-898410-85-2

- McDonald, R. Andrew, Outlaws of Medieval Scotland: Challenges to the Canmore Kings, 1058–1266. Tuckwell Press, East Linton, 2003. ISBN 1-86232-236-8

- Magnusson, Magnus, Scotland: The Story of a Nation. Atlantic Monthly Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0871137982

- Nield, Jonathan (1925), A Guide to the Best Historical Novels and Tales, G. P. Putnam's sons, ISBN 0-8337-2509-2

- Oram, Richard, David I: The King Who Made Scotland. Tempus, Stroud, 2004. ISBN 0-7524-2825-X

- Reid, Norman, "Kings and Kingship: Canmore Dynasty" in Michael Lynch (ed.), op. cit.

- Ritchie, R. L. Graeme, The Normans in Scotland, Edinburgh University Press, 1954

- Sturluson, Snorri, Heimskringla: History of the Kings of Norway, tr. Lee M. Hollander. Reprinted University of Texas Press, Austin, 1992. ISBN 0-292-73061-6

- Young, James, ed., Historical References to the Scottish Family of Lauder, Glasgow, 1884

External links

- Malcolm 5 at Prosopography of Anglo-Saxon England

- Orkneyinga Saga at Northvegr

- CELT: Corpus of Electronic Texts at University College Cork includes the Annals of Ulster, Tigernach and Innisfallen, the Lebor Bretnach and the Chronicon Scotorum among others. Most are translated or translations are in progress.

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Lulach |

King of Scots 1058–1093 |

Succeeded by Donald III |