Cumberland Gap

| Cumberland Gap | |

|---|---|

|

Cumberland Gap in winter | |

| Elevation | 1,631 ft (497 m)[1] |

| Traversed by |

|

| Location |

|

| Range | Cumberland Mountains |

| Coordinates | 36°36′14″N 83°40′23″W / 36.6039715°N 83.67297°WCoordinates: 36°36′14″N 83°40′23″W / 36.6039715°N 83.67297°W |

| Topo map | USGS Middlesboro South |

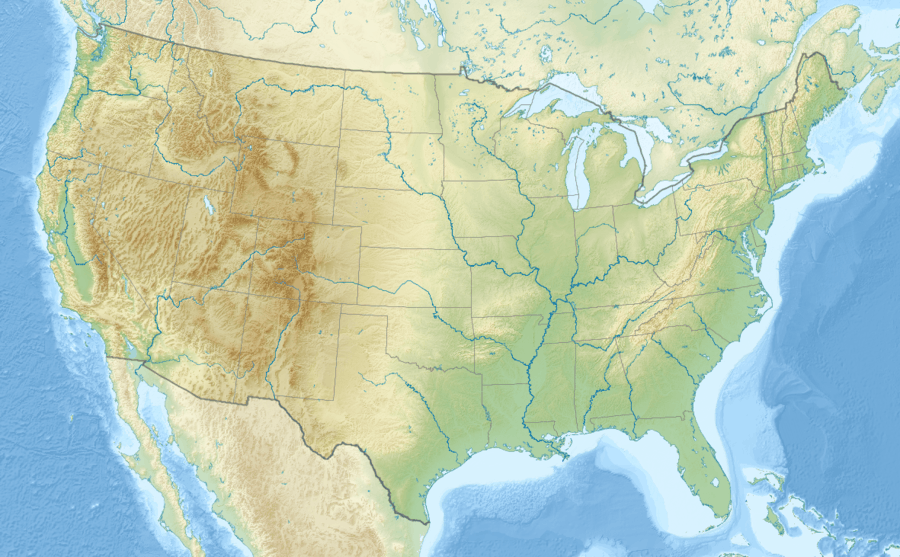

The pass is located in the southeastern United States | |

The Cumberland Gap is a narrow pass through the long ridge of the Cumberland Mountains, within the Appalachian Mountains, near the junction of the U.S. states of Kentucky, Virginia, and Tennessee.

Famous in American colonial history for its role as a key passageway through the lower central Appalachians, it was an important part of the Wilderness Road and is now part of the Cumberland Gap National Historical Park.

Long used by Native Americans, the Cumberland Gap was brought to the attention of settlers in 1750 by Dr. Thomas Walker, a Virginia physician and explorer. The path was explored by a team of frontiersmen led by Daniel Boone, making it accessible to pioneers who used it to journey into the western frontiers of Kentucky and Tennessee.

Geography

The Cumberland Gap is one of many passes in the Appalachian Mountains but the only one in the continuous Cumberland Mountain ridge line.[2] It lies within Cumberland Gap National Historical Park and is located on the border of present-day Kentucky and Virginia, approximately 0.25 miles (0.40 km) northeast of the tri-state marker with Tennessee.[3]

The area surrounding Cumberland Gap National Historical Park is composed of sedimentary rock, which is formed by the compaction of particles of gravel, sand, silt, mud, and carbonate minerals from the repetitive rise and fall of shallow seas. Scientists have dated this region to the Cambrian or Pennsylvanian period. The unique landscape seen today is a result of the uplift of sedimentary rock in conjunction with several million years of weathering and erosion. These features include narrow ridges, steep cliffs, overlooks, and natural gaps like the Cumberland Gap.[2] The Cumberland Gap is now known as a wind gap since water no longer flows through it.[4]

The V-shaped gap serves as a gateway to the west. The base of the gap is about 300 feet (91 m) above the valley floor below even though the north side of the pass was lowered 20 feet (6.1 m) during the construction of Old U.S. Route 25E. To the south the ridge rises 600 feet (180 m) above the pass, while to the north the Pinnacle Overlook towers 900 feet (270 m) above (elevation 2,505 feet (764 m)).[3]

Because it is centrally located in the United States, the region around Cumberland Gap experiences all four seasons. The summers are typically sunny, warm and humid with average temperatures in the mid to upper 90s F (30s C). In the winter months, January through March, temperatures range in the 30s to 40s F (0s C) and are generally mild with rain and few periods of snow.[5]

The nearest cities are Middlesboro, Kentucky, and Harrogate, Tennessee.

Geology

The gap was formed by the development of three major structural features: the Pine Mountain Thrust Sheet, the Middlesboro Syncline, and the Rocky Face Fault. Lateral compressive forces of sedimentary rocks from deep layers of the Earth's crust pushing upward 320 to 200 million years ago created the thrust sheet. Resistance on the fault from the opposing Cumberland Mountain to Pine Mountain caused the U-shaped structure of the Middlesboro Syncline. The once flat-lying sedimentary rocks were now deformed roughly 40 degrees northwest. Further constriction to the northwest of Cumberland Mountain developed into a fault trending north-to-south called the Rocky Face Fault, which eventually cut through Cumberland Mountain. This combination of natural geological processes created ideal conditions for weathering and erosion of the rocks.[2]

However, the discovery of the Middlesboro impact structure has proposed new details in the formation of Cumberland Gap. Less than 300 million years ago a meteorite, "approximately the size of a football field", struck the earth, creating the Middlesboro Crater.[2] One of three astroblemes in the state, it is a 3.7-mile (6.0 km) diameter meteorite impact crater[6] with the city of Middlesboro, Kentucky, built entirely inside it.[7] Detailed mapping by geologists in the 1960s led many to interpret the geological features of the area to be a site of an ancient impact.[2] In 1966 Robert Dietz discovered shatter cones in nearby sandstone, proving recent speculation. Shatter cones, a rock-shattering pattern naturally formed only during impact events, are found in abundance in the area. The presence of shatter cones found also helped confirm the origin of impact. In September 2003 the site was designated a Distinguished Geologic Site by the Kentucky Society of Professional Geologists.[6]

Without the Rocky Face Fault, it would have been difficult for pack-horses to navigate this gap and the gap in Pine Mountain near Pineville, and it would be improbable that wagon roads would have been constructed at an early date. Middlesboro is the only place in the world where coal is mined inside an astrobleme. Special mining techniques must be used in the complicated strata of this crater.[8]

History

The passage created by Cumberland Gap was well-traveled by Native Americans long before the arrival of European-American settlers. The earliest written account of Cumberland Gap dates to the 1670s, by Abraham Wood of Virginia.[9]

The gap was named for Prince William, Duke of Cumberland, son of King George II of Great Britain, who had many places named for him in the American colonies after the Battle of Culloden.[10] The explorer Thomas Walker gave the name to the Cumberland River in 1750, and the name soon spread to many other features in the region, such as the Cumberland Gap. In 1769 Joseph Martin built a fort nearby at present-day Rose Hill, Virginia, on behalf of Dr. Walker's land claimants. But Martin and his men were chased out of the area by Native Americans, and Martin himself did not return until 1775.[11]

In 1775 Daniel Boone, hired by the Transylvania Company, arrived in the region leading a company of men to widen the path through the gap to make settlement of Kentucky and Tennessee easier. On his arrival Boone discovered that Martin had beaten him to Powell Valley, where Martin and his men were clearing land for their own settlement – the westernmost settlement in English colonial America at the time.[12] By the 1790s the trail that Boone and his men built was widened to accommodate wagon traffic and sometimes became known as the Wilderness Road.

Several American Civil War engagements occurred in and around the Cumberland Gap and are sometimes called Battle of the Cumberland Gap. In June 1862, Union Army General George W. Morgan captured the gap for the Union. In September of that year, Confederate States Army forces under Edmund Kirby Smith occupied the gap during General Braxton Bragg's Kentucky Invasion. The following year, in a bloodless engagement in September 1863, Union Army troops under General Ambrose Burnside forced the surrender of 2,300 Confederates defending the gap, gaining Union control of the gap for the remainder of the war.

It is estimated that between 200,000 and 300,000 migrants passed through the gap on their way into Kentucky and the Ohio Valley before 1810. Today 18,000 cars pass beneath the site daily, and 1,200,000 people visit the park on the site annually.[13]

U.S. Route 25E passed overland through the gap before the completion of the Cumberland Gap Tunnel in 1996. The original trail was then restored.[14]

Historic district

The gap and associated historic resources were listed on the National Register of Historic Places as a historic district on May 28, 1980.[15]

Biology and ecology

Plants

Within the Cumberland Gap National Historical Park there are currently 855 known species of vascular plants identified, but that number is expected to increase with reports from National Park Service inventory and monitoring programs. There are 15 various vegetation communities throughout the park, with some of them in special locations, such as mountain bogs, low elevation wetlands, and rocky bluffs.[16]

Animals

Of the current 371 species of animals within the park, 33 are mammals, 89 are birds, 29 amphibians, 15 reptiles, 27 fish, and 187 are insects. Visitors to the park can expect to see gray squirrels, white-tailed deer, cottontail rabbits, songbirds, hawks, snakes, turtles, and perhaps black bear or bobcat.[17]

References in popular culture

Music

- "Cumberland Gap" (first recorded in 1924) is a popular folk song recorded and performed by American folk and bluegrass musicians such as Woody Guthrie and Earl Scruggs, and by British skiffle artists such as Lonnie Donegan and the Vipers Skiffle Group.

- The gap has been mentioned in many other songs, including:

- "The Ballad of Thunder Road"

- "Mighty Joe Moon", by American band Grant Lee Buffalo

- "Wagon Wheel", co-written by Bob Dylan and Ketch Secor, performed by the Old Crow Medicine Show

See also

References

- ↑ "Cumberland Gap". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved July 22, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Crawford, Matthew; Hunsberger, Hanna (2011). "Geology of Cumberland Gap National Historical Park" (PDF). Kentucky Geological Survey. University of Kentucky, Lexington. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- 1 2 Luckett, William (December 1964). "Cumberland Gap National Historical Park". Tennessee Historical Quarterly. Tennessee Historical Society. 23 (4). Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ↑ "Encyclopedic Entry: Gap". National Geographic Education. National Geographic Society. Retrieved July 31, 2014.

- ↑ "Profile for Cumberland Gap National Historical Park". weather.com. The Weather Channel. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- 1 2 Kortenkamp, Steve (Summer 2004). "Impact at Cumberland Gap: Where Natural and National History Collide" (PDF). PSI Newsletter. Planetary Science Institute. 5 (2): 1–2.

- ↑ "About Us". City of Middlesboro Kentucky. City of Middlesboro, KY. Retrieved July 31, 2014.

- ↑ Milam & Kuehn, 36

- ↑ Todd M. Ahlman; Gail L. Guymon; Nicholas P. Herrmann (July 2005). Archaeological Overview and Assessment of the Cumberland Gap National Historical Park, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Virginia (PDF). The Archaeological Research Laboratory, University of Tennessee.

- ↑ "VA-K1 Cumberland Gap". Historical markers. Archived from the original on 12 November 2013. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- ↑ Shattuck, Tom N. (1999). A Cumberland Gap Area Guidebook. The Wilderness Road Company. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-9677765-3-8.

- ↑ Morgan, Robert. Boone: A Biography. Chapel Hill: Algonquin Books. ISBN 978-1-56512-455-4.

- ↑ "Cumberland Gap".

- ↑ Longfellow, Rickie (17 Oct 2013). "Back In Time - The Cumberland Gap". Federal Highway Administration. U.S. Department of Transportation. Retrieved 22 July 2014.

- ↑ National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form: Cumberland Gap Historic District - Virginia/Kentucky/Tennessee, 1980

- ↑ "Plants: Cumberland Gap National Historical Park". National Park Service. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved 28 July 2014.

- ↑ "Animals: Cumberland Gap National Historical Park". National Park Service. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved 28 July 2014.

Further reading

- Kincaid, Robert L. (January 1941). "Cumberland Gap, Gateway of Empire". Filson Club History Quarterly. 15 (1). Retrieved 2011-11-30.

- The short film Cumberland Gap (1986) is available for free download at the Internet Archive

- Rickie Longfellow, Back in Time: The Cumberland Gap, United States Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration