Dark photon

| Beyond the Standard Model |

|---|

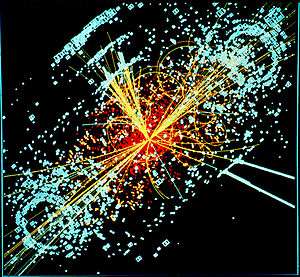

Simulated Large Hadron Collider CMS particle detector data depicting a Higgs boson produced by colliding protons decaying into hadron jets and electrons |

| Standard Model |

The dark photon is a hypothetical elementary particle, proposed as an electromagnetic force carrier for dark matter.[1] Dark photons would theoretically be detectable via their mixing with ordinary photons, and subsequent effect on the interactions of known particles.[1]

Dark photons were proposed in 2008 by Lotty Ackerman, Matthew R. Buckley, Sean M. Carroll, and Marc Kamionkowski as the force carrier of a new long-range U(1) gauge field, "dark electromagnetism", acting on dark matter.[2] Like the ordinary photon, dark photons would be massless.[2]

Dark photons were suggested to be a possible cause of the so-called 'g–2 anomaly' obtained by experiment E821 at Brookhaven National Laboratory,[3] which appears to be three to four standard deviations above the Standard-Model values of Hagawara et al.[4] and Davier et al.[5] However, dark photons were largely ruled out as a cause of the anomaly by several experiments, including the PHENIX detector at the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider at Brookhaven.[1] A new experiment at Fermilab, the Muon g-2 experiment, expects to produce a precision four times better than the Brookhaven experiment.[6]

More generally, a dark photon is any spin-1 boson associated with a new U(1) gauge field. That is, any new force of nature that arises in a theoretical extension of the Standard Model and generally behaves like electromagnetism. Unlike ordinary photons, these models often feature a dark photon that is unstable or possesses non-zero mass, rapidly decaying into other particles such as electron-positron pairs. They may also interact directly with the known particles, like electrons or muons, if said particles are charged under the new force.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Walsh, Karen McNulty (February 19, 2015). "Data from RHIC, other experiments nearly rule out role of 'dark photons' as explanation for 'g-2' anomaly". PhysOrg. Retrieved 23 February 2015.

- 1 2 Carroll, Sean M. (October 29, 2008). "Dark photons". Retrieved 23 February 2015.

- ↑ Bennett, G. W.; Bousquet, B.; Brown, H. N.; Bunce, G.; Carey, R. M.; Cushman, P.; Danby, G. T.; Debevec, P. T. (2006-04-07). "Final report of the E821 muon anomalous magnetic moment measurement at BNL". Physical Review D. 73 (7): 072003. arXiv:hep-ex/0602035

. Bibcode:2006PhRvD..73g2003B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.73.072003.

. Bibcode:2006PhRvD..73g2003B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.73.072003. - ↑ Hagawara, Kaoru; Liao, Ruofan; Martin, Alan D.; Nomura, Daisuke; Teubner, Thomas (June 23, 2011). "(g − 2)μ and α(M2Z) re-evaluated using new precise data". Journal of Physics G: Nuclear and Particle Physics. IOP Publishing. 38 (8). arXiv:1105.3149

. Bibcode:2011JPhG...38h5003H. doi:10.1088/0954-3899/38/8/085003. Retrieved 10 December 2015.

. Bibcode:2011JPhG...38h5003H. doi:10.1088/0954-3899/38/8/085003. Retrieved 10 December 2015. - ↑ Davier, M.; Hoecker, A.; Malaescu, B.; Zhang, Z. (January 2011). "Reevaluation of the hadronic contributions to the muon g−2 and to α(M2Z)". The European Physical Journal C. Springer-Verlag. 71. arXiv:1010.4180

. Bibcode:2011EPJC...71.1515D. doi:10.1140/epjc/s10052-010-1515-z. ISSN 1434-6052. Retrieved 10 December 2015.

. Bibcode:2011EPJC...71.1515D. doi:10.1140/epjc/s10052-010-1515-z. ISSN 1434-6052. Retrieved 10 December 2015. - ↑ "Muon g-2 Experiment". Fermilab. Retrieved 10 December 2015.